Sanctions, CBDCs, and the Role of ‘Decentral Banks’ in Bretton Woods III

In a world with two parallel financial systems, a country would not necessarily have a single reserve bank.

In a recent conversation on the Odd Lots podcast, Zoltan Pozsar offered an interesting use case for central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), a potentially transformative technology that 86 percent of central banks are “actively researching” according to a BIS survey from 2021.

Pozsar, a former Credit Suisse strategist who is setting up his own research outfit, believes that a new global monetary order is emerging—he calls it “Bretton Woods III.” As part of this order, the adoption of CBDCs will enable central banks to play a more pivotal role in global trade through the formation of a “state-to-state” network that is intended to be independent of Western financial centres and the dollar. In this network, central banks will play a “dealer” role when it comes to providing liquidity for trade among developing economies. Commenting on China’s push to internationalise the renminbi, Pozsar set out his vision:

You need to imagine a world where five, ten years from now we are going to have a renminbi that’s far more internationally used than today, but the settlement of international renminbi transactions are going to happen on the balance sheets of central banks. So instead of having a network of correspondent banks, we should be thinking about a network of correspondent central banks and a world where you have a number of different countries and in which each of those different countries have their banking systems using the local currency but when country A wants to trade with country B… The [foreign exchange] needs of those two local banking systems are going to be met by dealings between two central banks.

In short, Pozsar believes that the adoption of CBDCs will enable the creation of a “new correspondent banking system” built around central banks. But even if central banks do begin to use CBDCs to settle trade, reducing dependence on dollar liquidity and legacy correspondent banking channels, the underlying problem motivating CBDC adoption will remain.

Moving away from the dollar-based financial system is foremost about geopolitics. Globalisation, as we have known it, reinforced a unipolar order. The United States was able to leverage its unique position in the global economy into unrivalled superpower status. In the last two decades, the weaponisation of the dollar further augmented U.S. power—Americans are uniquely able to wage war without expending military resources, which is another kind of exorbitant privilege. As Pozsar notes, the countries moving fastest towards CBDCs are those that are either currently under a major U.S. sanctions program (Russia, Iran, Venezuela etc.) or at risk of being targeted (China, Pakistan, South Africa etc.) These countries recognise “that it is pointless to internationalise your currency through a Western financial system… and through the balance sheets of Western financial institutions when you basically do not control that network of institutions that your currency is running through.” As Edoardo Saravalle has argued, the power of U.S. sanctions is actually underpinned by the central role of the Federal Reserve in the global economy.

Adopting CBDCs would enable countries to reduce the proportion of their foreign exchange reserves held in dollars while also reducing reliance on U.S. banks and co-opted institutions such as SWIFT to settle cross-border payments. However, even if countries reduce their exposure to the dollar-based financial system in this way, U.S. authorities will still be able to use secondary sanctions to block central banks from the U.S. financial system for any transaction with a sanctioned sector, entity, or individual. Any financial institution still transacting with a designated central bank could likewise find itself designated.

Moreover, even if Bretton Woods III emerges, leading to the formation of a robust parallel financial system that is not based on the dollar, central banks will continue to engage with the legacy dollar-based financial system. It is difficult to image a central bank correspondent banking network in which nodes are not shared between the dollar-based and non-dollar based financial networks. As such, the threat of secondary sanctions or being placed on the FATF blacklist—moves that would cut a central banks access to key dollar-based facilities—will remain a significant threat.

Even Iran, which is under the strictest financial sanctions in the world, including multiple designations of its central bank, continues to depend on dollar liquidity provided through a special financial channel in Iraq. A significant portion of Iran’s imports of agricultural commodities continue to be purchased in dollars. Iran earns Iraqi dinars for exports of natural gas and electricity to its neighbour. The Iraqi dinars accrue at an account held at the Trade Bank of Iraq. The dinar is not useful for international trade, and so Iran converts its dinar-denominated reserves into dollars to purchase agricultural commodities—a waiver issued by the U.S. Department of State permits these transactions. The dollar liquidity is provided by J.P. Morgan, which plays a key role in the Trade Bank of Iraq’s global operations, having led the creation of the bank after the 2003 invasion.

The fact that the most sanctioned economy in the world depends on dollar liquidity for its most essential trade suggests that central banks will remain subject to U.S. economic coercion, owing to continued use of the dollar for at least some trade. But even in cases where Iran conducts trade without settling through the dollar, U.S. secondary sanctions loom large.

For over a decade, China has continued to purchase large volumes of Iranian oil in violation of U.S. sanctions, paying for the imports in renminbi. Iran is happy to accrue renminbi reserves because of its demand for Chinese manufactures. But owing to sanctions on Iran’s financial sector, Iranian banks have struggled to maintain correspondent banking relationships with Chinese counterparts. When the bottlenecks first emerged more than a decade ago, China tapped a little-known institution called Bank of Kunlun to be the policy bank for China-Iran trade.

The bank was eventually designated by the US Treasury Department in 2012. Since then, Bank of Kunlun has had no financial dealings with the United States, but that has not eased the bank’s transactions with Iran. Bank of Kunlun is owned by Chinese energy giant CNPC, an organisation with significant reliance on U.S. capital markets. When the Trump administration reimposed secondary sanctions on Iran in 2018, Bank of Kunlun informed its Iranian correspondents that it would only process payment orders or letters of trade in “humanitarian and non-sanctioned goods and services,” a move that was intended to forestall further pressure on CNPC. Ultimately, Bank of Kunlun had far less exposure to the U.S. financial system that China’s own central bank ever will, a fact that points to the limits of a central bank correspondent banking network. For CBDCs to serve as a defence against the weaponised dollar, they would need to be deployed by institutions that maintain no nexus with the dollar-based financial system. It is necessary to think beyond central banks.

What Pozsar has failed to consider is that in a world with two parallel financial systems, a country would not necessarily have a single reserve bank. Alongside central banks, we can envision the rise of what I call decentral banks. If a central bank is a monetary authority that is dependent on the dollar-backed financial system and settles foreign exchange transactions through the dollar, a decentral bank is a parallel authority that steers clear of the dollar-backed financial system and settles foreign exchange transactions through CBDCs. The extent to which Bretton Woods III really represents the emergence of a new bifurcated global monetary order depends not only on the adoption of CBDCs, but also the degree to which the innovations inherent in CBDCs enable countries to operate two or more reserve banks whose assets and liabilities are included in a consolidated sovereign balance sheet.

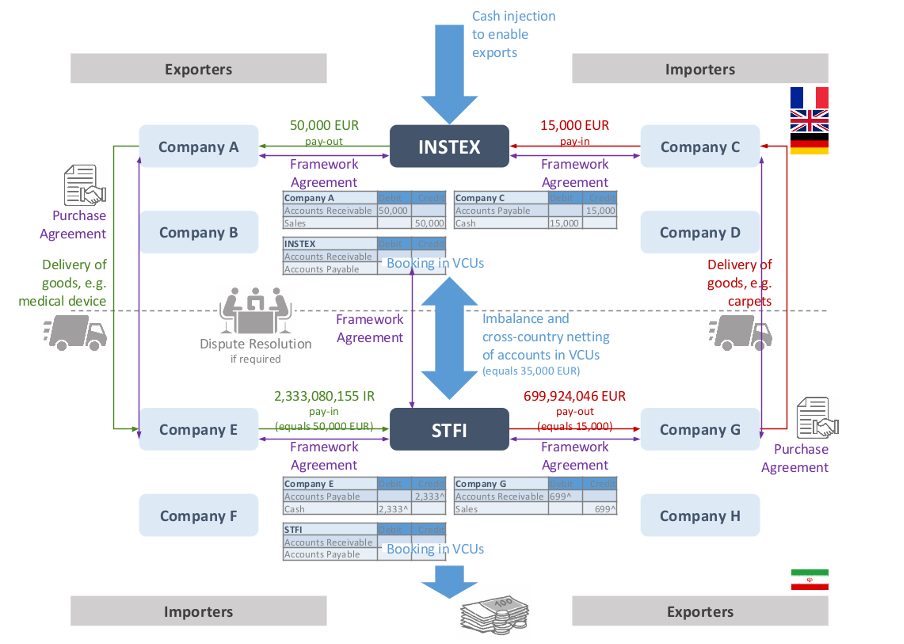

Again, Iran offers an interesting case study for what this innovation might look like. The reimposition of U.S. secondary sanctions on Iran in 2018 crippled bilateral trade between Europe and Iran. Conducting cross-border financial transactions was incredibly difficult owing to limited foreign exchange liquidity and the dependence on just a handful of correspondent banking relationships. France, Germany, and the United Kingdom took the step to establish INSTEX. As a state-owned company, INSTEX would work with its Iranian counterpart, STFI, to establish a new clearing mechanism for humanitarian and sanctions-exempt trade between Europe and Iran. The image below is taken from a 2019 presentation used by the management of INSTEX to explain how trade could be facilitated without cross-border financial transactions.

The model is strikingly like Pozsar’s suggestion that CBDCs will enable central banks to settle trades using their balance sheets, rather than relying on the liquidity of banks and correspondent banking relationships. INSTEX and STFI were supposed to net payments made by Iranian importers to European exporters with payments made by European importers to Iranian exporters, using a “virtual currency unit” to book the trade. The likely imbalances would be covered by a cash injection into INSTEX (Europe was exporting far more than it was importing after ending purchases of Iranian oil). It was an elegant solution, which sought to scale-up the methods being used by treasury managers at multinational companies operating in Iran to purchase inputs and repatriate profits.

Earlier this year, INSTEX was dissolved. Its shareholders, which eventually counted ten European states, lacked the political fortitude to see the project through. Notwithstanding bold claims about preserving European economic sovereignty in the face of unilateral American sanctions, there was always a sense among European officials that Iran was undeserving of a special purpose vehicle. But as the world moves to a new financial order, more institutions like INSTEX will emerge. Pozsar’s vision is bold insofar as he believes central banks will establish new cross-border clearing mechanisms based on CBDCs. But if new digital currencies can emerge to displace the dollar in the global monetary order, so too can new institutions be established.

Pozsar’s vision for Bretton Woods III becomes more convincing if one considers that the emergence of institutions such as decentral banks could lead to the creation of correspondent banking networks that are truly divorced from the dollar-based financial order. However, there remain plenty of reasons to doubt that such a system will emerge. Pozsar appears to have given little consideration to the issue of state capacity. Most countries have poorly managed central banks as it is—in the Odd Lots interview he pointed to Iran and Zimbabwe as early movers on CBDCs. We should have low expectations for the ability of most governments to develop and implement new technologies such as CBDCs or to establish wholly new institutions such as decentral banks. Moreover, the ability of the U.S. to use carrots and sticks to interfere with those efforts should not be underestimated.

There may be compelling structural drivers for something like Bretton Woods III, namely the rise of China and the overall shift in the global distribution of output. But somewhere along the way those structural drivers need to be converted into institutional processes. Bretton Woods is shorthand for the idea that monetary rules are as important for the operation of the global economy as the macroeconomic fundamentals. Countries reluctant to break the rules will struggle to rewrite them.

Photo: Canva

Iran Trade Mechanism INSTEX is Shutting Down

At the end of January, the board of Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX) took the decision to liquidate the company.

At the end of January, the board of the Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX) took the decision to liquidate the company. Established in January 2019 by the United Kingdom, France, and Germany, INSTEX’s shareholders later came to include the governments of Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands, Finland, Spain, Sweden, and Norway.

The state-owned company had a unique mission. It was created in response to the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal in May 2018. European officials understood that the reimposition of US sanctions would impede European trade with Iran. The nuclear deal was a straightforward bargain. Iran had agreed to limits on its civilian nuclear programme in exchange for the economic benefits of sanctions relief. If European firms were unwilling or unable to trade with Iran, that basic quid-pro-quo would be undermined. For this reason, supporting trade with Iran was seen as a national security priority.

In August 2018, EU high representative Federica Mogherini and foreign ministers Jean-Yves Le Drian of France, Heiko Maas of Germany, and Jeremy Hunt of the United Kingdom, issued a joint statement in which they committed to preserve “effective financial channels with Iran, and the continuation of Iran’s export of oil and gas” in the face of the returning US sanctions. They pointed to a “European initiative to establish a special purpose vehicle” that would “enable continued sanctions lifting to reach Iran and allow for European exporters and importers to pursue legitimate trade.”

In November 2018, when the basic parameters of a special purpose vehicle were still being formulated by European officials, I co-authored the first public white paper explaining why establishing such a company made sense. Conversations with European and Iranian bankers and executives had made clear to me that trade intermediation methods were being widely used to get around the lack of adequate financial channels between Europe and Iran. If these methods could be packaged as a service by an entity backed by European governments, it would reassure European companies about remaining engaged in the Iranian market, while also reducing costs.

A few months later, INSTEX was founded. In the beginning, the company was run by the Iran desks at the EU and E3 foreign ministries. The officials tasked with working on INSTEX, who were often very junior, quickly realised they had little knowledge of the mechanics of EU-Iran trade. When they sought to enlist help from colleagues at finance ministries and central banks, they frequently met resistance. Many European technocrats were reluctant to support a project which had the overt aim of blunting US sanctions power, even at a time when figures such as French finance minister Bruno Le Maire and Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte were making bold statements about the need for European economic sovereignty. Even INSTEX’s inaugural managing director, Per Fischer, departed given concerns over his association with a company that had been maligned by American officials as a sanctions busting scheme. Then, in May 2019, when the Trump administration cancelled a set of sanctions waivers, European purchases of Iranian oil ended. That left INSTEX as Europe’s only gambit to preserve at least some of the economic benefits of the nuclear deal for Iran.

Later that year, INSTEX hired its first real team after a new group of European governments joined as shareholders and injected new capital into the company. For a time, things looked more promising. Under the newly appointed president, former German diplomat Michael Bock, a small group of talented individuals worked to define INSTEX’s mission and build a commercial case for the company’s operation. Their efforts led to INSTEX’s first transaction, which was completed in March 2020—the sale of around EUR 500,000 worth of blood treatment medication. The political pressure to provide Iran some gesture of tangible support during the pandemic had also greased the wheels in European governments.

But many considered the INSTEX project doomed even before the first transaction was completed. Certainly, Iranian officials were derisive of the special purpose vehicle. Given that Europe had failed to sustain its imports of Iranian oil and was unable to use INSTEX for that purpose, focusing instead on humanitarian trade, Iranian officials dismissed the effort, even after the feasibility of the special purpose vehicle was proven. That it took more than a year to process the first transaction also meant that the Europeans missed their chance to fill the vacuum caused by the US withdrawal from the nuclear agreement. Without full cooperation from its Iranian counterpart, which was called the Special Trade and Finance Instrument (STFI), INSTEX could not reliably net the monies owed by European importers to Iranian exporters with those owed by Iranian exporters to European importers.

European officials will no doubt blame Iran for the fact that INSTEX failed, and it is true that the Iranian government never fully appreciated the political significance of European states taking concrete steps to counteract even the indirect effects of US sanctions. Of course, the decision to liquidate the company follows a spate of recent actions by the Iranian government—nuclear escalation, the sale of drones to Russia, and the brutal repression of protests—that make the continued operation of INSTEX politically untenable.

But most of the blame for INSTEX’s failure must lie with the Europeans—the company’s demise predates Iran’s recent transgressions. European officials promised a historic project to assert their economic sovereignty, but they never really committed to that undertaking. A mechanism intended to support billions of dollars in bilateral trade was provided paltry investment. European governments never figured out how to give INSTEX access to the euro liquidity needed to account for the fact that Europe runs a major trade surplus with Iran when oil sales are zeroed out. For the Iranians, this alone was the evidence that European leaders saw INSTEX as a political gesture that might placate Tehran, rather than an economic instrument that would bolster Iran’s economy in the face of Trump’s “maximum pressure.”

Paradoxically, Iran will lose nothing as the liquidators shut down INSTEX, quietly selling the few assets the company had accumulated—laptops, office chairs, and perhaps some nifty pens. It is Europe that is losing out. INSTEX was supposed to be a testbed for new ways of facilitating trade without relying on risk-averse banks to process cross border transactions. Successful innovation in this area would have given a new dimension to European economic diplomacy and helped Europe assert the power of the euro in global trade.

With the writing on wall, INSTEX’s management made one final attempt to give the company a future. Beginning in 2021, the company pursued a French banking license—a pivot that INSTEX’s board had approved on a provisional basis, but which was halted in early 2022. It is hard to overstate how significant it would have been had INSTEX emerged as a state-owned bank with a specific mandate to process payments on behalf of European companies that wish to work in high-risk jurisdictions, including those under broad US sanctions programme. Such a bank could have become a powerful tool for Europe to assert its economic might in the face of US sanctions. Moreover, it would even have been useful in cases where Europe is applying sanctions, like Russia. After all, a commitment to humanitarianism means that goods such as food and medicine must continue to be bought and sold even when most transactions with a given country are prohibited. INSTEX could have helped make European sanctions powers more targeted and more humane.

For a company that managed just one transaction, a surprising amount has been written about INSTEX. It has been the subject of news reports, think pieces, and academic articles. Even if many people struggled to understand what the special purpose vehicle aimed to do, its existence was novel and therefore noteworthy. For those insiders directly involved in the company’s saga, and for those of us who have closely followed from the outside, the main takeaway seems to be that there is much yet to be learned about the complex ways in which US sanctions impact European policy towards countries like Iran, through both political and economic vectors. In this respect, INSTEX did achieve something. A group of technocrats in European foreign ministries and finance ministries learned valuable lessons, often reluctantly and with great difficulty, about the limits of Europe’s economic sovereignty. Whether those lessons can be institutionalised remains to be seen. But a fuller post-mortem on INSTEX would no doubt offer important lessons for the future of European economic power in a world dominated by US sanctions. Learning those lessons would be its own special purpose.

Photo: Wikicommons

After UN Showdown, INSTEX Can Help Sustain Iran Nuclear Deal

INSTEX alone cannot save the JCPOA, the future of which essentially depends on US-Iranian relations. INSTEX can nevertheless help maintain the nuclear agreement until, or even after, diplomatic solutions are found.

In return for limits to Iran’s nuclear activities under the 2015 agreement, or the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the other side—the United States, the EU/E3 (France, Germany and the UK), China and Russia—were supposed to lift sanctions on the country. The US opted out of this compromise in May 2018 by withdrawing from the JCPOA. By deterring most private sector actors from Iran-related activities, US secondary sanctions have also prevented other JCPOA parties from living up to their end of the deal. In addition to a deep socio-economic crisis within Iran, US sanctions have undermined Iranian people’s access to basic humanitarian goods--and pushed the country to reduce its nuclear commitments. The EU and E3 efforts to protect the JCPOA under these circumstances have offered a grim lesson about the limits of European autonomy in a dollar-dominated world economy.

When the Trump administration withdrew from the JCPOA, the EU stressed its commitment to ensuring continued sanctions lifting and to upholding the agreement. This determination was also expressed in practical measures. In summer 2018 the EU included the upcoming US sanctions on Iran in the so-called Blocking Regulation, thus banning EU companies from complying with them. In September 2018 the EU and the E3 announced that they would develop a special trade instrument to facilitate European-Iranian trade, including in oil, which was to be targeted by US secondary sanctions.

However, the Trump administration’s obliviousness to the Blocking Regulation soon exposed the absence of an effective enforcement mechanism to enforce it, and in practice US law took priority over EU law in the private sector’s risk assessments. Apparently recognizing their lack of political and economic leverage over US policy, by January 2019 the E3 had reduced the mission of the trade instrument—then named Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX)— to trade in humanitarian goods.

While its limited focus fell short of previous expectations that the EU could counter or even significantly minimize the negative effects of US sanctions, INSTEX addresses a critical problem created by them. Humanitarian trade, which is in principle exempt from sanctions, has also been hit by the banking sector’s fear of US penalties, leading to a medicine shortage in Iran. In addition to being urgent, addressing this particular area of sanction over-compliance is also practical, as humanitarian trade runs a lower risk of being targeted by US sanctions than other trade areas.

INSTEX seeks to enable the exchange of humanitarian goods or services between Europe and Iran without the transfer of currency, thus minimizing the risk of US penalties. European exporters are to be compensated with funds located in Europe, based on the value commensurate with the value of imports from Iran. INSTEX’ Iranian counterpart, the Special Trade and Finance Instrument (STFI), is similarly tasked to coordinate payments within Iran.

INSTEX can reassure banks and companies through its joint ownership by the E3 and four other European states—Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands and Norway, as well as Finland and Sweden, which are expected to join soon. In addition to providing a high level of trust in the instrument’s due diligence procedures, governmental ownership raises the threshold for the USA to impose sanctions on INSTEX.

Having processed only one pilot transaction thus far, INSTEX still needs to overcome major obstacles to function as intended. One key challenge is that the value of European exports to Iran exceeds the value of Iranian exports to Europe. Potential solutions to the problem include paying European exporters using Iran’s revenues currently frozen in foreign banks, or offering Iran a loan to buy humanitarian goods. However, the US is seeking to block these options.

The chances of striking a functioning trade balance could also be increased through the expansion of INSTEX to non-European companies, and extension of the INSTEX mandate to non-humanitarian trade that are not targeted by the USA but are impeded by fear of secondary sanctions. While INSTEX is unlikely to deliberately go against US sanctions, the E3 might decide to take further steps to protect is economic sovereignty if the instrument is targeted by the USA.

Currently it might seem that INSTEX is being taken over by political events, in particular the 2020 US presidential elections. Democratic Party victory in the elections could open the door for the US re-entry into the JCPOA, which would appear to make INSTEX less relevant. However, restoring the JCPOA or reaching any new agreements with Iran is dependent on sanctions lifting. This is likely to be difficult given the private sector’s disillusionment with the Obama administration’s previous assurances about the safety of engaging with Iran. INSTEX could help address this problem by providing additional guarantees to risk-averse banks and companies fearing the next U-turn in US policy towards Iran.

Alternatively, the possibility of Trump’s re-election as US president—or a snapback of UN Security Council sanctions on Iran—could lead to the collapse of the JCPOA. While this can be expected to reduce European commitment to INSTEX, its humanitarian mission should be pursued as a matter of ethical necessity, even without the JCPOA.

Clearly, INSTEX alone cannot save the JCPOA, the future of which essentially depends on US-Iranian relations. INSTEX can nevertheless help maintain the nuclear agreement until, or even after, diplomatic solutions are found. In addition to demonstrating solidarity on the JCPOA and commitment to basic humanitarian principles, INSTEX can also been seen as a test case of a more independent European foreign policy.

Photo: IRNA

How Europe Can Help Iran Fight COVID-19

The Iranian healthcare system is reliant on long-standing relations with European suppliers to see it through the COVID-19 crisis. European governments should press the US to strengthen the humanitarian exemptions in its Iran sanctions.

This analysis was originally published by the European Council on Foreign Relations.

Iran became an early epicentre of the COVID-19 outbreak due to its close political and economic relations with China. Yet the Iranian healthcare sector overwhelmingly depends on European medicine and medical devices—products that China has been unable to replace. While the European Union and its member states must prioritize their own fight against the virus, they should also protect this important humanitarian connection with Iran.

The Iranian healthcare system is reliant on long-standing relations with European suppliers to see it through the crisis. If there is a grave breakdown in either this supply chain or Iran’s healthcare sector, it will spell trouble for Europe. Given that Iran continues to be the epicenter of the pandemic in a fragile Middle East, the coronavirus is likely to lead to increased refugee flows (particularly among Afghan communities) to Europe. Despite their conflicting opinions on the leadership in Tehran, Europe’s Iranian diaspora community – who, until recently, often travelled to Iran – broadly agree on the need for enhanced humanitarian assistance to Iran, which could save hundreds of thousands of people.

Following two years of recession linked to systematic mismanagement, falling oil prices, and the unique pressure created by US sanctions, Iran’s government is facing extreme trade-offs between the optimal public healthcare response and the need to prevent a full-blown economic crisis. These sanctions hamper Iran’s immediate response to COVID-19.. Despite their humanitarian exemptions, the measures make the import of medicine and medical equipment – as well as the raw materials needed to produce many of these goods in Iran – both slower and more expensive. This erodes the capacity of the Iranian healthcare system to replenish its inventories as Iran’s outbreak moves into its third month. Moreover, the Iranian government cannot afford the type of economic stimulus packages that governments across the globe have implemented to reduce the impact of lockdowns.

While the US has made general offers to send aid to Iran, leaders in Tehran will perceivethem as disingenuous for so long as the sanctions are in place. Given the sharp downturn in US-Iranian relations under the Trump administration, it is unrealistic to think that either the United States will provide full sanctions relief or that Iran will accept aid from a country it believes to be pursuing regime change in Tehran. Although the more hard-line elements within the Iranian system are suspicious of European assistance (as recently reflected in Iran’s sudden rejection of aid from Médecins Sans Frontières), there is some breathing room for the country to cooperate with Europe on this front.

Building on recent announcements by the EU, France, the United Kingdom, and Germany, European governments should continue to provide financial assistance and other aid to Iran’s public healthcare system and trusted NGO partners working in the country. European companies can also boost humanitarian trade via the Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX) – which has now processed its first transaction, targeting Iran’s core public healthcare needs in the fight against COVID-19..

The European Commission has implemented export controls on key items in the fight against COVID-19, to minimize shortages in Europe. This move puts Iran and other low-income and developing countries at even greater risk, given their significant reliance on European exports. Rather than cut these supply chains, which forces Iran to turn to China and Russia, the EU should explore whether Iran could ramp up its production of basic medical equipment, such as surgical masks, to help meet demand in Europe. This would allow European manufacturers to focus on the production of more advanced items, such as face shields – the surplus of which it could/ sell to Iran.

Most importantly, European governments and the EU should press the US to strengthen the humanitarian exemptions in its sanctions. European leaders should urge the US Treasury to expand and clarify the scope of these exemptions to directly include products Iran needs to combat COVID-19 effectively. Such clarification, which could take the form of a “white list” of goods, should allow European companies to apply General License No. 8, under which the Central Bank of Iran can help facilitate humanitarian trade.

Given the unprecedented humanitarian fallout from the COVID-19 crisis, European governments should also urge the US administration to issue comfort letters to European banks that already conduct enhanced due diligence on trade with Iran. This would help reassure these banks that the US Office of Foreign Assets Control will not penalise them for providing payment channels to exporters of humanitarian goods. The Trump administration recently took the unprecedented step of issuing such a letter to Swiss bank BCP under the Swiss Humanitarian Trade Arrangement. As former US official Richard Newphew has argues, the US could provide similar letters to manufacturers and transport firms, helping reassure companies across the entire medical supply chain that they can facilitate sales to Iran.

While the International Monetary Fund reviews Iran’s $5 billion loan request, European governments should press the Trump administration to temporarily allow Tehran to access Iranian foreign currency reserves. In this, the administration could restore the escrow system that enabled Iran to use its accrued oil revenues to purchase humanitarian goods prior to May 2019. These funds (including those in Europe) could be subject to existing enhanced due diligence requirements and spent within the countries in which they are currently located. The funds in Europe could also be linked to INSTEX.

Such US measure could be connected to humanitarian steps by Iran, not least the release of American detainees. In particular, France and the UK – some of whose nationals Tehran has released from prison (either permanently or temporarily) in recent weeks – should stand ready to support these efforts. Europeans actors should emphasize that targeted relief need not change the substance of the Trump administration’s policy on Iran or reduce its leverage in potential negotiations with the country. Should Europe and the US fail to provide relief to Iran in such grave circumstances, this would turn the Iranian public against them for generations. And it would give ammunition to those in Iran who favor confrontation with the West.

Photo: IRNA

Europe-Iran Trade Mechanism Completes Landmark Iran Sale

The Germany foreign ministry has announced that INSTEX, the trade mechanism backed by nine European states to facilitate humanitarian trade with Iran, has completed its first transaction.

The Germany foreign ministry announced on Tuesday that INSTEX, the Iran trade mechanism backed by nine European states, has completed its first transaction.

"France, Germany and the United Kingdom confirm that INSTEX has successfully concluded its first transaction, facilitating the export of medical goods from Europe to Iran. These goods are now in Iran," the ministry said in a statement.

An individual with knowledge of the transaction, speaking on background, said that a German exporter had used the INSTEX mechanism to receive payment for the sale of medication to an Iranian private sector importer. The transactions was later reported to be worth EUR 500,000.

The sale is consistent with INSTEX’s initial mission to facilitate humanitarian trade, currently impinged by the impact of U.S. secondary sanctions on banking ties between Europe and Iran.

Officially launched in January 2019, INSTEX was slow to operationalize as French, German, and British officials grappled with the political and technical challenges of establishing a novel state-owned trade mechanism.

But in the summer of last year, INSTEX hired its first managing director and expanded its team, leading to a step-change in the company’s operations.

The new management resisted pressure to conclude an initial transaction as soon as possible—European officials had explored providing a factoring service as a stopgap—and instead sought facilitate a sale that would utilize the cross-border clearing mechanism. Through this mechanism, INSTEX makes payments to European exporters on behalf of Iranian importers, reducing the transaction costs associated with Europe-Iran trade. These sales are netted against exports made by Iranian companies, who are paid in turn by INSTEX’s Iranian counterpart, STFI.

INSTEX management has been working on several transactions in parallel, on the back of strong interest from European exporters to engage the mechanism. The German foreign ministry statement concludes, “INSTEX and its Iranian counterpart STFI will work on more transactions and enhancing the mechanism.”

Photo: IRNA

Europe Still Needs INSTEX to Help Solve the Iran Crisis

At a time when constructive diplomatic relations between Europe and Iran may prove instrumental in efforts to stave off a regional conflict, the speedy operationalization of INSTEX remains an imperative—a point underscored by EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell following his first trip to Tehran earlier this month.

This article was originally published by the European Leadership Network.

Over the last few months, the mission of INSTEX has grown significantly more complicated. Tensions between the United States and Iran have reached new highs following the assassination of Iranian Major General Qassem Soleimani, and European leaders have called for de-escalation as fears grow of direct conflict. Iran’s recent elections, marked by historically low turnout, have ushered in a more conservative parliament, sceptical of Western intentions. Already hamstrung by delays, the intended political function of INSTEX—to encourage Iran to remain in compliance with the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)—has been thrown further into doubt.

However, at a time when constructive diplomatic relations between Europe and Iran may prove instrumental in efforts to stave off a regional conflict, the speedy operationalisation of INSTEX remains an imperative—a point underscored by EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell following his first trip to Tehran earlier this month.

INSTEX has quietly increased the tempo of its consultations with its Iranian counterpart, the Special Trade and Finance Instrument (STFI), in Tehran and other European capitals. The project was buoyed by the decision of six European countries–Belgium, the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, and Norway–to join the company as shareholders.

The new shareholders will provide further capital to enable INSTEX to grow its team and operational capacity. Having relied on support from staff at E3 foreign and economic ministries until late last year, INSTEX now has its own full-time staff members. The new hires have helped the company present itself more credibly with key stakeholders in Europe and Iran who now perceive the company to be a serious, long-term undertaking.

As has been reported, a first transaction was nearly completed on the eve of the December 6 meeting of the JCPOA Joint Commission. But rather than pursue quick wins, INSTEX and STFI are now resolved that the first transactions serve as a proof-of-concept for the operationalisation of the core service.

The core service INSTEX will offer, which can be referred to as a “cross-border clearing mechanism,” aims to eliminate the need for companies trading goods and services between Europe and Iran to make payments between the financial systems of the two jurisdictions. At a time when few European banks are willing to send or receive Iran-related payments, INSTEX can help make European trade with Iran both more reliable and affordable.

INSTEX has made progress in defining its onboarding procedures and compliance guidelines as part of an overall business model designed in collaboration with a wide range of stakeholders. The company is now in a position to ramp-up its engagement with potential clients this year, and there is a significant interest among European enterprises. Until now, such interest has been channelled through companies’ respective foreign ministries. Importantly, these companies are not only small and medium enterprises but also include major multinational companies with active sales or manufacturing business in Iran. The wide-range of interest is critical information for INSTEX as it begins its own proactive outreach.

INSTEX intends to be less expensive than all other payment solutions available to conduct trade with Iran. The significant transaction costs associated with foreign exchange conversions and wire transfers currently required to conduct trade between Europe and Iran have been a significant driver of the increased cost of imports, particularly humanitarian goods, adding to inflationary pressure in Iran and hardship for ordinary Iranians. The goal is to deliver a solution that facilitates trade at a meaningful scale to help ameliorate these conditions.

This has been the main point of scepticism about INSTEX—a severe imbalance in trade has been taken to mean that the value of Iranian exports to Iran will act as a ceiling for the value of trade that can be cleared through the mechanism. Here, those familiar with INSTEX express confidence. Working with E3 policymakers, INSTEX has identified a source for the required liquidity, allowing the mechanism to work without perfect balance in credits and liabilities.

There have also been longstanding concerns that the reimposition of countermeasures by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) might interfere with the operationalisation of INSTEX. But given the robust due diligence framework established by INSTEX, Iran’s return to the so-called FATF “blacklist” is not expected to prevent the mechanism from maintaining the banking services necessary for its operation.

While the business case and operational model for INSTEX are clearer than ever before, the company continues to face political headwinds in Washington, European capitals, and Tehran. The first transaction is being pursued at precisely the moment when both the American government is doubling down on “maximum pressure” and European and Iranian governments are reconsidering their strategies in light of wider developments.

European governments have opted to trigger the JCPOA’s Dispute Resolution Mechanism (DRM) given growing concerns regarding Iran’s progressive steps to reduce its compliance with the agreement’s nuclear restrictions and the eroded credibility of the agreement’s credibility as a non-proliferation agreement. Triggering the DRM will no doubt complicate the overall political environment, particularly as UN and EU sanctions snapback remains a possibility should the subsequent negotiations fail to address concerns. But there remain several clear reasons why European and Iranian authorities should proceed with the operationalisation of INSTEX.

First, trade in food and medicine will remain permissible even if EU sanctions are reimposed as demonstrated by the perseverance of European economic operators active in the sale of food and medicine during the sanctions period of 2008-2016. There is a clear role for INSTEX to play in safeguarding and facilitating humanitarian trade even in a scenario where Europe-Iran diplomatic ties deteriorate considerably. In this sense, even if INSTEX fails to save the Iran nuclear deal, its innovative mechanism has a role to play as a tool for humane European foreign policy and the defence of European economic sovereignty.

Second, Iran has emerged as an epicentre of the global public health crisis caused by the spread of the COVID-19 coronavirus. Iranian authorities have already received support and diagnostic kits from the World Health Organization as they seek to contain the spread of the virus, which has so far killed at least sixteen people. Should the public health crisis in Iran intensify, further medication and equipment may be needed. Presently, the indirect effect of sanctions on humanitarian trade makes it difficult for Iranian authorities to source products from new suppliers—onerous due diligence requirements for humanitarian trade discourage financial institutions from onboarding new clients. Such restrictions may encumber Iran’s response to the coronavirus. INSTEX can be used to ensure Iran remains able to make payments to European suppliers and receive speedy and reliable deliveries of the equipment necessary to deal with the coronavirus outbreak.

Finally, as made clear in the aftermath of the assassination of Qassem Solaimani, tensions between the United States and Iran may yet lead to outright war. The Iranian escalatory steps that would contribute to the initiation of any such conflict would no doubt test European resolve to operationalise INSTEX as presently intended. However, in the context of war, Europe’s humanitarian obligations will be even more important. Facilitating the flow of food and medicine to the Iranian population will be crucial should Europe wish to reduce harm to the civilian population and present itself as a credible mediator between the United States and Iran. In this context, and given the existing pressures on humanitarian trade, an operational INSTEX would be a crucial tool for peace-minded European foreign policy. In short, further political and economic investment in the INSTEX project is consistent with European preparedness for such worst-case scenarios.

European policymakers have few tools with which to influence the direction of the brewing security, economic, and public health crises in the Middle East. Against this backdrop of uncertainty and instability, INSTEX deserves greater high-level political support as a key means by which Europe can reassert its credibility as the only major global actor whose economic operators are significantly invested in the economic and humanitarian wellbeing of the people of Iran and the wider Middle East.

Photo: IRNA

Iran Needs Humanitarian Aid. Trump Should Help.

Medicines and foodstuffs are exempted from the U.S. sanctions on Iran, but the prospect of punishment has spooked potential suppliers, and especially foreign banks. Although this problem is easily fixed, President Donald Trump’s administration has been shamefully tardy in doing so.

It was the smallest of gestures, and might easily have been missed if it wasn’t for the identities of those involved. In the chamber of the United Nations Security Council on Thursday, the American ambassador to the UN walked over to her Iranian counterpart to offer condolences.

Kelly Craft was responding to a speech by Majid Takht-Ravanchi, in which the Iranian ambassador mourned the death of Ava, a two-year-old girl in Tehran, whose doctors had been unable to procure bandages for skin blisters caused by a rare genetic disease. Takht-Ravanchi blamed U.S. sanctions — specifically, their impact on supplies of essential medicines.

It would’ve been easy enough to dismiss the story as a disingenuous play for sympathy, and an opportunistic attempt to deflect blame by a regime that has in recent weeks slaughtered hundreds of its own citizens—including children. But Craft was right to express compassion for the plight of ordinary Iranians. In fact, a bigger, more meaningful gesture is long overdue: making sure no other Ava need die for her government’s faults.

Medicines and foodstuffs are exempted from the U.S. sanctions on Iran, but the prospect of punishment has spooked potential suppliers, and especially foreign banks. Although this problem is easily fixed, President Donald Trump’s administration has been shamefully tardy in doing so.

What it will take is for the U.S. to green-light a proposed Swiss channel for humanitarian trade, and to expand the channel’s mandate to include non-Swiss suppliers. The channel has been in the works for more than a year. The most obvious European beneficiaries would be Swiss drugmakers Roche Holding AG and Novartis AG, and the food group Nestle SA, which have a long history of trade with Iran. But there’s no logical reason other companies, even American ones, shouldn’t be allowed to use the conduit.

U.S. authorities have blocked the channel, mainly by dragging their feet in clarifying what they would and would not allow through it. Some progress was announced in October, and still more earlier this month.

This isn’t good enough. While it’s true that the Iranian regime uses the sanctions as a convenient cover for its own failings — and some of the medical shortages are of its own making — there’s no gainsaying that trade restrictions inflict real pain on many people. Human-rights groups have documented how the sanctions harm Iranians’ right to health.

At the same time, they have encouraged European governments to seek alternative routes such as INSTEX, a so-called “special purpose vehicle” designed to sidestep the American financial system. It hasn’t worked yet. But it has put the Trump administration in the unedifying position of threatening its allies over humanitarian trade.

American intransigence on this has also given Iran a stick with which to beat the Europeans. When not shedding crocodile tears over Ava, the regime in Tehran threatens to ratchet up its enrichment of uranium, unless Europe opens up trade channels.

By clearing the legal and bureaucratic path for the Swiss channel, the Trump administration would not only be doing the right thing by the Iranian people, it would be revealing the regime’s threats for what they are: nuclear blackmail. It would also free the Europeans to impose sanctions of their own, guilt-free.

All of this is long overdue. But if politics requires a propitious moment for the big gesture, it so happens that one is close at hand: January marks the 40th anniversary of Switzerland’s role as the de-facto representative of American interests in Tehran. It’s hard to think of a better time to announce a Swiss-American humanitarian channel.

And should the channel need a name, something more meaningful than “INSTEX,” something that conveys a political message as well as a humanitarian one ... how about Ava?

Photo: IRNA

After the Iran Protests: How Europe Can Keep Diplomacy Alive

The aftermath of the protests presents significant challenges for the Iranian leadership. The Islamic Republic is dealing with severe economic difficulties and a fraying of the political fabric. Washington will use the recent unrest to argue against Europe engaging with Tehran. But diplomacy remains the only viable path to deescalation. Europeans, led by Emmanuel Macron, must protect the space for dialogue.

This article was originally published by the European Council on Foreign Relations.

The Middle East is facing a wave of protests—with the latest unrest in Iran sweeping the country in November. For the moment, a swift government crackdown that reportedly left at least 208 dead has largely brought the protests to an end. An unprecedented internet shutdown during the unrest means that information and debate from inside Iran are now going viral, with observers seeking to take stock of what it could mean for the country. While much remains unclear, the episode has shaken a fragile Iranian nation, diminished the already dwindling popular support for the Rouhani administration, and further complicated European efforts to reduce tensions between the United States and Iran.

The protests were sparked after Iranians woke up to steep hikes in petrol prices of around 50 percent brought in overnight in mid-November. The Iranian state has long subsidized fuel, but Iranian officials argued that this was a necessary step to address the budget deficit (hard hit by US sanctions cutting off oil revenues) and to tackle illicit fuel-smuggling organizations. The new approach has also allowed an increase in cash transfer subsidies to Iran’s poorest.

The move predictably provoked the greatest anger among Iran’s lower earners, who are barely making ends meet. People immediately took to the streets to voice their fury at the decision, and at the political establishment more broadly. Similar to the last round of protests in Iran in late 2017 and early 2018, most of those who participated appeared to be young and from lower-income households. However, while the unrest in 2017 and 2018 stretched out over a longer period and remained largely peaceful, the latest protests were short-lived, with signs of greater coordination among those that took to the streets and hard-headed action by state authorities in response.

Some Iranian interlocutors from the policy community view the crackdown by the security apparatus as reflective of panic and anxiety in the Iranian security establishment. But others believe the Iranian state felt confident and strong in taking these actions, that it was ready to communicate its preparedness to immediately quash any serious threat, and to introduce a state of fear before protests spread further.

The aftermath of the protests presents significant challenges for the Iranian leadership. The Islamic Republic is now a pressure cooker, dealing with an unprecedented degree of harsh US sanctions that are have brought about severe economic difficulties, and a fraying of the political fabric. If economic reforms are not forthcoming to weather the storm of sanctions, tackle corruption, and provide relief to Iranian households, Iran will likely face periodic protests with ever higher levels of state repression.

For Rouhani himself, expectations were already low for the parliamentary election due in February. Now, given the brutal repression of these protests, growing numbers of those members of Iran’s middle class that previously backed the president are now likely to avoid political participation. And, over the past year, Iran’s Reformist faction, which had allied with Rouhani’s centrist presidential campaign, has conducted a fierce debate about whether to stand in the election given huge disappointment at the pace of reforms. Recent events have only intensified this debate. Hardliners are therefore expected to make significant gains in parliament and make life much tougher for Rouhani in the final year of his presidency.

Rouhani’s weakened position will make it even more difficult for him to push through any form of pro-diplomacy policy in his last year. The president has repeatedly stated that he is open to negotiations with the US given the right parameters—and he reiterated this after the end of the recent protests. Powerful figures inside Iran, such as the Supreme Leader and senior figures within the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, have rejected the possibility of such negotiations, but Rouhani still has some limited ammunition. This was demonstrated by the recent detainee exchange between Iran and the US—a small but noteworthy sign of diplomatic success.

How far Rouhani can move forward will be influenced not just by internal dynamics but also by the US and Europe. The response by Iranian authorities to the protests complicates the political optics for European governments seeking to provide Iran with economic benefit to sustain the nuclear deal, which now hangs by a thread. Moreover, Washington will likely use the state repression inside Iran to double down against European engagement with Tehran, arguing that there are no moderate actors for change within the Iranian leadership.

Despite these pressures, European governments can still strike the right balance on Iran. Amid the protests, the EU called for “maximum restraint” from Iran. And the newly appointed EU high representative, in a stern statement, called for “credible investigations” into the events. European governments can also consider calling for a special session at the United Nations Human Rights Council to press for impartial investigations into the use of force in the recent protests in both Iran and Iraq.

In parallel, Europe should still move forward with processing the first transactions through the Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX). This should be rooted in a duty of care towards the Iranian people, namely that Europe acknowledges the severe economic pressures placed on Iranians following the reimposition of US sanctions. Europeans must remain focused on facilitating quicker and cheaper access to humanitarian goods for the Iranian people. If this can simultaneously help prevent a further unravelling of the nuclear deal, this would be no bad outcome.

Greater internal pressure combined with increased weakness for Rouhani will likely push Iran towards a more confrontational stance, and diminish Rouhani’s ability to pursue political solutions. The US and Iran have already twice recently come dangerously close to military conflict, following Iran’s downing of the US drone in June and attacks against Saudi Arabia’s Aramco oil facility in September. US intelligence officials reportedly believe that Iran has increased its stockpile of short-range missiles inside Iraq, and military officials have warned of potential impending attacks by Iran. If the country continues to be suffocated economically by US sanctions, it will continue its withdrawal from the nuclear deal and up the ante in the region.

In the meantime, it is imperative that Emmanuel Macron pursue his initiative to reduce tensions between Tehran and Washington. Senior US officials have vowed to continue the “maximum pressure” campaign, and its proponents are likely to view the recent protests as proof that the policy is working. But Europeans should make clear that the policy has so far backfired in terms of softening Iran’s posture on the nuclear and regional files and only succeeded at pushing the country into a greater state of securitization and internal oppression. Macron should seek to quickly use the positive, and most likely short-lived, political momentum from the US-Iran detainee exchange to impress on both sides that diplomacy can deliver concrete outcomes, and that it is much the preferred option to another cycle of escalation.

Photo: IRNA

Why Iran Pays More for Each Kilogram of European Medicine

◢ Since the year 2000, Iran has about doubled its annual imports of pharmaceutical products from the European Union, reflecting both advances in Iranian healthcare and the growth in Europe-Iran trade ties. But a distortion in the value of trade relative to quantity means that Iran is paying significantly more than the likes of Russia, Turkey, and Pakistan for each kilogram of medication.

Since the year 2000, Iran has about doubled its annual imports of pharmaceutical products from the European Union, reflecting both advances in Iranian healthcare and the growth in Europe-Iran trade ties. This growth has remained durable in the face of multilateral—and more recently—unilateral sanctions. Pharmaceutical products can be sold under longstanding humanitarian exemptions under both the US and EU sanctions regimes.

Yet, reporting from Iran has highlighted the significant disruptions in the price and availability of many medications in Iran. Iranian medical professionals complain that despite the exemptions, sanctions are making it more difficult for patients to reliably and affordably access medication. US officials have countered that there has not been an dramatic drop in pharmaceutical exports to Iran, but their defense relies on an incomplete picture of the nature of the trade disruption. Iranian patients are not principally struggling because of a supply disruption. They are suffering because of a price distortion that can be observed in the relationship between the quantity of European pharmaceutical exports to Iran, and the declared value of those exports.

To contextualize the distortions in European pharmaceutical exports to Iran, it is possible to conduct Pearson correlation analyses for the quantity and value of monthly pharmaceutical exports from the European Union to Russia, Turkey, Pakistan, and Iran for the period between January 2000 and June 2019. Intuitively, we would expect that an increase in the quantity of exports from Europe to these countries would be correlated with an increase in the declared value of those exports—if Europe is selling more it should be earning more.

This is clearly the case when looking to European pharmaceutical exports to Russia, Turkey, and Pakistan in this period. The observed correlations are strongly positive and statistically significant. However, the underlying data tell slightly different stories for each country. In the case of Russia, the magnitude of the increase in the value of exports since 2000 has been greater than the increase in quantity. In Turkey, the opposite is true. To put it more simply, Russia is buying slightly more medicine at a significantly higher price, while Turkey is buying significantly more medicine at a slightly higher price. That is an observation that deserves its own analysis, but in the context of understanding comparative differences with Iranian purchases of European medicine, what matters is that in both cases an increase in quantity of medicine exported correlates with an increase in the value of medicine exported.

The data for Russia, Turkey, and Pakistan shows relatively low levels of volatility. This can be seen when the value and quantity of monthly exports are indexed. Fluctuations each month can be explained by a range of factors such as seasonal or cyclical demand, as well as variation in the composition of exports, particularly in terms of price. Many medicines weigh roughly the same amount, but have vastly different prices—consider the price of aspirin and the price of pills used in the treatment of rare diseases.

Sudden spikes in pharmaceutical exports are often related to disaster response. The December 2005 spike in European exports to Pakistan corresponds to the 2005 Kashmir earthquake, which killed nearly 90,000 people. The August 2010 spike in exports to Russia corresponds to a weeks long heatwave that led to thousands of deaths and triggered extensive wildfires.

Putting these spikes in context, and looking to fluctuations over time, we see that the expected relationship holds—the greater the quantity of pharmaceutical products exported from Europe to Russia, Turkey, and Pakistan, the greater the declared value of those exports.

In the case of Iran, the expected relationship also holds, but not so definitively. Looking to the period between January 2000 and June 2019, the correlation between quantity of exports and value of exports is still positive and statistically significant, but is notably weaker. The explanation becomes clear when looking at a chart of indexed export quantity and value. Sales of European pharmaceutical products to Iran are marked by huge volatility. In more recent years, it appears that the declared value of exports has increased without a commensurate increase in the quantity.

There has been extensive reporting on the impact of sanctions on Iran’s ability to reliably important pharmaceutical products. To test whether the relative weakness in the relationship between export quantity and value is sanctions related, it is possible to test the relationship in two time periods. Multilateral sanctions on Iran reached their apogee in July 2012, when the United States imposed strict sanctions intended to cut off Iranian banks from the global financial system. The number of correspondent banking relationships dwindled, meaning that even for trade in pharmaceuticals, which remained an exempted category, European exporters and Iranian importers faced significant challenges in identifying viable banking channels. When such channels were found, their use typically entails higher transaction costs and payment delays.

Looking to the period prior to July 2012, we can observe a moderately positive and statistically significant correlation between export quantity and value. When limiting the analysis to the period after July 2012, that relationship is only weakly positive. This is a remarkable finding, suggesting that since 2012, the price paid by Iranian importers for European pharmaceuticals is only loosely related to the quantity of goods ordered. Sanctions may have exacerbated whatever factors led the relationship between quantity and value to be weaker than that observed for Russia, Turkey, and Pakistan.

As a consequence of the weakened relationship between quantity and value, Iranian importers are paying significantly more for each kilogram of European medication they purchase than importers in Russia, Turkey, or Pakistan. In the period between June 2018 and June 2019, European exports to Iran can be “priced” at EUR 8464 for each 100 kilograms exported. By comparison, exports to Russia were just EUR 5707 for each 100 kilograms, while exports to Turkey were EUR 5645. In the case of Russia and Turkey there may be economies of scale at play—the value of monthly European pharmaceutical exports to these countries are on average 9 and 3.5 times higher, respectively, than those to Iran. But even Pakistan, which imports less than half the pharmaceutical products that Iran imports from Europe each month, benefits from a significantly lower price of EUR 7509 per 100 kilograms. Taking the average of the price enjoyed by Russia, Turkey, and Pakistan, in the most recent 12 months for which data is available, Iran paid EUR 2723 more for each 100 kilograms of pharmaceutical products. This premium is almost certainly being passed onto consumers, with devastating effects.

It is difficult to say to what extent distortions in Europe-Iran pharmaceutical trade are attributable to sanctions impacts. Certainly Turkey, Russia, and Pakistan do not share the same experience of being targeted by unilateral and multilateral sanctions, though they do share many of the same political and economic risk factors that can serve as an impediment to bilateral trade. There are other possible explanations for Iran’s highly volatile pharmaceutical imports, including issues related to the devaluation of the Iranian rial, the use of middlemen in transactions, and changes in the composition of imports related to protectionist policies.

Looking to total relative proportion of total export quantities in 2018, it is possible to take a snapshot of the composition of European exports to the four countries. What we find is that the composition of exports is broadly similar, with nearly all of the top ten export categories for Iran represented among the top ten for Russia, Turkey, and Pakistan, albeit with differences in proportion. What is clear is that all of the countries import significant volumes of pharmaceutical ingredients, such as vitamins, for use in domestic pharmaceutical manufacturing. Iran imports significantly more vitamin E than the other countries, but significantly less wadding. Neither is a particularly expensive good.

What is most remarkable about the price distortion is that it can be observed through European customs data. In this data, the value of goods is reflective of the value declared by the European seller at time of export. This distinguishes the analysis here from reports focusing on the price increases observed by Iranian consumers. It would appear that at least some of the exorbitant increases in the price of medication for Iranians are attributable to disruptions in trade that originate outside of Iran, rather than tariffs, hoarding, price gouging, or other market disruptions that are known to exist within Iran.

The price distortion also challenges the conception of sanctions impacts on pharmaceutical trade as being principally about reduced export volumes or shortages within Iran. The analysis presented here suggests that European pharmaceutical exports to Iran could theoretically grow in both absolute value and quantity under sanctions, and yet there could still be harms felt by Iranian consumers if the price of medication continues to rise unchecked. This means that sanctions policy cannot be defended on the basis that trade data shows limited disruption in the value or quantity of exports. The price related disruption shown here only becomes clear when looking to the relationship between export value and quantity over time. Any significant increase in the price of medication at time of export will necessarily lead to circumstances where the sick and dying in Iran cannot afford the medication they need.

Photo: IRNA

INSTEX Develops New Service in Bid to Fast-Track Iran Transactions

◢ The state-owned company at the center of European efforts to save the Iran nuclear deal is entering its next phase of development. In a push to process transactions more quickly, INSTEX is rolling out a new factoring service for European exporters. The company is also making new hires that will enable it to expand operations more quickly in the coming year.

The state-owned company at the center of European efforts to save the Iran nuclear deal is entering its next phase of development. In a push to process transactions more quickly, INSTEX is rolling out a new factoring service for European exporters. The company is also making new hires that will enable it to expand operations in the coming year.

Having reached the end of his six-month contract, Per Fischer is stepping down as the president of INSTEX, the state-owned company established by France, Germany, and the United Kingdom to support trade with Iran. Fischer’s replacement is former German ambassador to Iran Bernd Erbel. A career diplomat, Erbel has been posted in Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt, and served as ambassador to Iraq prior to his stint as ambassador to Iran.

The change in leadership comes as INSTEX finalizes several other management hires. By filling these roles, INSTEX will enter a new phase of operation as a standalone company based in Paris. Until now, both INSTEX’s outreach to European companies and its coordination with its Iranian counterpart, STFI, has been led by civil servants at the foreign and economy ministries of the company’s three founding shareholders.

Fischer, a former Commerzbank executive, had been selected as the company’s first president due to his banking background. But Erbel, who lacks commercial experience, will have a different mission as he assumes his leadership role. Erbel will leave key commercial responsibilities to the new managers, focusing instead on ensuring a constructive working relationship between INSTEX and STFI. In recent weeks, cooperation between the two entities has slowed. Iranian authorities have called for INSTEX to be funded by Iran’s oil revenues—a move that would leave INSTEX vulnerable to sanctions from the United States.

Erbel’s deep knowledge of Iran may help him navigate the tensions surrounding the INSTEX project in Tehran and reassure Iranian stakeholders of the seriousness of European efforts to develop the mechanism further.

The goal for INSTEX remains to ease Europe-Iran trade by developing a netting mechanism that eliminates the need for a cross-border financial transactions. In this model, INSTEX will coordinate payment instructions between companies engaged in bilateral trade between Europe and Iran, enabling European exporters to receive payment for sales to Iran from funds that are already within Europe. The counterpart entity, STFI, will then mirror those transactions, allowing Iranian exporters to get paid with funds already in Iran.

Delayed by political disagreements, INSTEX and STFI remain in the process of establishing the netting mechanism. But in a bid to fast-track transactions, INSTEX has opted to roll out a new service that does not require the direct participation of its Iranian counterpart. INSTEX is now in advanced negotiations to a provide factoring service to an initial cohort of European companies.

In factoring transactions, INSTEX will purchase the expired invoices of European exporters who have failed to receive payment for sanctions-exempt goods sold to Iran. The focus on expired invoices allows INSTEX to avoid lengthy French regulatory approvals for a full factoring service. Importantly, INSTEX will not require the goods in question to have been delivered to the Iranian buyer in order for the European exporter to factor its receivables. In this sense, the service approximates a kind of trade finance.

According to a draft contract between INSTEX and a European company seen by Bourse & Bazaar, the purchase price paid to the European exporter by INSTEX would amount to 95 percent of the “assigned receivable.” In other words, INSTEX will charge a 5 percent fee as part of its factoring service. This fee will vary based on the transaction.

Such costs are not negligible for European exporters, especially when considering that INSTEX will require each transaction to undergo third-party due diligence at the exporter’s expense. Yet they are commensurate with the transaction fees typically charged by banks in those cases in which the bank is willing to accept funds originating in Iran. Moreover, for European companies burdened with unpaid invoices, the certainty of payment from INSTEX, a state-owned European company, is inherently attractive.

In some respects, the factoring service is a more appealing solution for companies than the netting mechanism service which INSTEX still intends to operationalize. However, factoring is inherently less scalable as it requires significant capital to be made available to INSTEX in order purchase invoices. INSTEX will also assume the burden of seeking payment from the Iranian debtor.

However, should the factoring solution prove popular, it may be the case that INSTEX could subsequently transfer its newly assigned receivables to STFI, making it possible for Iranian importers to pay STFI for goods purchased from European exporters. Alternatively, INSTEX could open an account either in Iran or at the Iranian bank branch based in Europe in order to receive payment for the outstanding invoices. While conceived as a stopgap solution, the experience with factoring could help INSTEX develop a more robust netting mechanism.

As it welcomes new leadership and pivots to a new service, INSTEX resembles any ordinary startup at a key stage of its development. Like all startups, INSTEX continues to face many hurdles—its success is far from assured, particularly in the darkening political climate. But the individuals responsible for its development are responding to pressure from demanding shareholders and skeptical customers with creative solutions—an encouraging sign.

Photo: Anna McMaster

Trump Administration May Use Patriot Act to Target Iran Humanitarian Trade

◢ The Trump administration has imposed successive rounds of economic sanctions targeting nearly all productive sectors of Iran’s economy. But a new wave of restrictive measures now under consideration would have the practical effect of totally severing Iran’s economy from Europe, critically undermining humanitarian trade with Iran.

The Trump administration has imposed successive rounds of economic sanctions targeting nearly all productive sectors of Iran’s economy. These sanctions have been imposed with conflicting objectives in mind, up to and including regime change. But a new wave of restrictive measures now under consideration would have the practical effect of totally severing Iran’s economy from Europe, critically undermining humanitarian trade with Iran. Considering Europe’s renewed motivation to inaugurate INSTEX—the special purpose vehicle through which Europe and Iran will facilitate non-sanctioned trade—the Trump administration’s action could undermine months of high-level diplomatic efforts to save the nuclear accord by entirely eviscerating the limited leverage that Europe possesses with respect to Iran moving forward. This is the likely intention.

Section 311 and Iran

Section 311 of the USA Patriot Act—which was enacted in response to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States—provides authority for the Secretary of the Treasury to designate a foreign jurisdiction, institution, class of transactions, or type of account to be of “primary money laundering concern” and thereby requiring US financial institutions to take “special measures” with respect to them. This authority has been used in relation to foreign countries such as Burma, North Korea, and Ukraine, as well as foreign financial institutions such as ABLV Bank, Banco Delta Asia, Bank of Dandong, and the Lebanese Canadian Bank. The “special measures” imposed with respect to each “money laundering concern” can range from certain minimal record-keeping and reporting requirements to a total ban on the maintenance of correspondent or payable-through accounts.

In November 2011, as part of its own campaign to ramp up the sanctions pressure on Iran, the Obama administration found Iran to be a jurisdiction of primary money laundering concern and proposed the imposition of the fifth special measure pursuant to Section 311. This “special measure” prohibits the opening or maintaining of a correspondent or payable-through account by a US bank for a foreign financial institution if the correspondent account involves Iran in any manner. In addition, the fifth “special measure” requires US banks to apply “special due diligence” with respect to all of their correspondent accounts to ensure that such accounts are not used indirectly to provide services to an Iranian financial institution.

The proposed rule never took effect during the Obama administration’s tenure, as the growing sanctions pressure on Iran made finalization of the rule superfluous and little more than a bureaucratic headache. The Obama administration had accomplished the intended purpose of the rule regardless, as Iran’s banking sector was left isolated and ostracized on the global stage—its reputation muddied by the Section 311 finding and the proposed rule. Once negotiations commenced between the US and Iran with respect to Iran’s nuclear program, the Section 311 rule-making was thrust aside—the Obama administration more immediately focused more on how to lift sanctions than how to impose additional ones.

Treasury’s New Move

But Section 311 rule-making appears to be back with a vengeance. The Trump administration is mulling the issuance of a “Final Rule” that would give the Section 311 designation the force of law. In doing so, the administration would impose the fifth special measure with respect to Iran. The administration’s outside enablers are quickly laying the public groundwork for Treasury’s imminent action. The effects could prove dramatic.

The most significant result of such rule-making could well be the total cessation of humanitarian trade with Iran, as those few foreign banks that maintain accounts for non-designated Iranian banks to facilitate legitimate trade with Iran—including humanitarian trade—shutter such accounts in order to avoid the onerous scrutiny of their US correspondents.