Prospects for Syrian Civil Society Remain Dim While Sanctions Linger

Without tangible sanctions relief, Syrian civil society organisations will struggle to play a meaningful role in the country’s constitutional reform, local governance, or transitional justice efforts.

Last month, Syrian civil society actors, sanctons experts, and European officials gathered in The Hague to assess the role of sanctions in Syria’s political and economic transition following the fall of Damascus to Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). During a one-day workshop co-hosted by the Bourse & Bazaar Foundation and the Clingendael Institute, participants discussed how Western sanctions policy should be adjusted to alleviate Syria’s desperate economic situation. The gathering focused on ensuring meaningful support to local institutions and civil society, with the ambition of preventing the country from spiraling into renewed conflict.

Syria remains under multiple overlapping sanctions regimes led by the United States, the European Union, and the United Nations. These measures—originally designed to pressure the Assad regime—now inhibit economic recovery, reconstruction, and institutional reform, even though the political landscape has shifted.

The US regime, shaped by the Caesar Act and counterterrorism designations of HTS, is the most comprehensive and extraterritorial. General License 24, set to expire in July 2025, provides narrow exemptions focused on essential services but does not allow for new investment or broader engagement. The EU has taken steps to suspend sanctions on key sectors, including energy and transport, yet the extraterritorial effect of US sanctions limits the impact of EU moves. The UN still lists HTS under its 1267 regime, restricting international financial and diplomatic engagement.

While the legal frameworks differ, the overall effect is similar: financial institutions, aid agencies, and the private sector are reluctant to engage in Syria, fearing compliance risks and political fallout.

Participants described the Syrian economy as being in a state of accelerating collapse, with deteriorating civil services, soaring unemployment, and households struggling without purchasing power. The destruction of infrastructure, ongoing currency depreciation, and the withdrawal of Russian and Iranian economic support have compounded the crisis. Streets in Damascus are flooded with cheap Turkish imports that Syrians cannot afford. Even in now stable areas of the country, public utilities and services—electricity, water, telecommunications, education—are barely functional.

Against this backdrop, humanitarian needs are escalating, yet aid pledges remain grossly inadequate. According to estimates, Syria’s reconstruction needs range between $250 and $400 billion, while the March 2025 Brussels donor conference resulted in pledges amounting to just $6.5 billion. Even early recovery and resilience programming—technically permissible under many sanctions frameworks—remains underfunded and politically delayed.

Despite the continued implementation of sanctions, participants noted that the international donor community is not entirely constrained from engaging with Syria. Under existing exemptions and mandates, there are already pathways for supporting essential services, infrastructure rehabilitation, and early recovery efforts—particularly when these activities are framed as humanitarian or development aid. According to one workshop participant, the World Bank has confirmed that it can support infrastructure and basic services in Syria under its post-conflict operational framework. However, meaningful engagement still depends on greater clarity and political alignment from member states. If expanded and adequately resourced, the Bank’s early recovery programs could offer a critical lifeline to communities even in the absence of full-scale sanctions relief.

Failure to lift or ease sanctions will prevent private sector and institutional investment that is essential for rebuilding the Syrian economy. But failure to increase aid, even under the current legal frameworks, ensures continued suffering, deepens instability, and risks the re-emergence of violence, organised crime, and extremism.

A central theme in the discussions was the counterproductive reliance on political benchmarks—such as inclusivity, constitutional reform, and governance transformation—as preconditions for sanctions relief. While these conditions seem sensible, they have triggered a rushed and top-down political process in Syria that many civil society organisations (CSOs) described as inorganic and externally driven.

For example, the national dialogue conference was announced to many of its intended participants with less than 24 hours’ notice. Consultations were limited in scope and representation, with key civic figures and regions underrepresented. Similarly, the interim constitution was drafted in just weeks, concentrating power in the executive, offering minimal separation of powers, and making vague commitments to pluralism.

HTS has made symbolic gestures to show its commitment to inclusive governance, such as appointing technocrats and making deals with Druze, southern militias, and Kurdish factions. Civil society actors view these many of these moves as superficial and tailored to meet donor expectations rather than domestic realities. Many warned that the political process risks collapsing without parallel efforts to restore economic viability and institutional functionality.

Moreover, the current sanctions framework often fails to distinguish between political conditionality and humanitarian necessity. As one participant remarked, “you cannot expect people to fight for democracy when fighting for food.”

Syrian civil society actors at the workshop identified several priorities for supporting an inclusive and grounded transition. Chief among them was the need for clearer guidance on sanctions and access to channels for clarification from relevant authorities. Many CSOs, especially those returning from abroad, are eager to establish offices in Damascus but face significant challenges due to legal uncertainties and the degraded infrastructure. Establishing local operations is constrained by the lack of electricity and internet access in particular, two utilities affected by sanctions.

Participants also emphasised the importance of providing training and technical support to ensure compliance with evolving sanctions frameworks, especially around financial procedures and institutional engagement. Access to dedicated funding with simplified disbursement processes, along with protections against bank over-compliance, was also flagged as essential.

In addition, CSOs called for increased support for local governance and service delivery, including civil servant salaries and early recovery programmes. They urged international actors to move away from a narrow focus on minority protection and instead promote a shared civic rights agenda. Finally, participants highlighted the need for more unified CSO advocacy efforts to engage international partners with a coherent voice representing diaspora and in-country actors.

Without these resources, CSOs will struggle to play a meaningful role in Syria’s constitutional reform, local governance, or transitional justice efforts. The current imbalance between international expectations and the limited capabilities of civil society risks undermining its legitimacy—not only in the eyes of donors, but also among ordinary Syrians. When CSOs are unable to address pressing socioeconomic needs like livelihoods, essential services, and infrastructure, they can appear ineffective or disconnected from the reality on the ground. As one participant noted, if civil society is perceived as focused solely on political processes while daily conditions worsen, public trust and relevance may quickly erode.

In response to these concerns, participants proposed a set of actionable steps for international actors to align sanctions policy with Syria’s evolving circumstances. For the United States, the immediate priority is to make General License 24 permanent and broaden its scope to include investment and infrastructure-related activities. Participants also urged Washington to remove HTS’ designation as a Foreign Terrorist Organisation (FTO) while maintaining its listing as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist (SDGT), at least for now. This modest move would reduce the legal risks associated with engagement while preserving necessary safeguards for the population. Alongside these steps, it was suggested the US should issue more explicit guidance on permissible engagements in Syria—such as FAQs or advisory notes tailored to humanitarian and development actors—to reduce uncertainty and risk aversion.

While the European Union has gone further than the US in suspending sanctions, it still plays a key role. Participants noted that the EU’s suspension of sectoral sanctions, enacted in February, is effectively permanent, but called for an outline of a transparent roadmap towards full sanctions removal. Additionally, they recommended launching an EU-led reconstruction trust fund that is both insulated from US financial jurisdiction as well as open to co-financing from Gulf states and multilateral actors. Restoring a diplomatic and technical presence on the ground would also assist the EU in monitoring developments in Syria, ultimately supporting a more credible political and economic transition.

Crucially, the EU must actively encourage the United States to take bolder and more decisive steps. Without parallel US action, the efficacy of EU measures remains limited, especially given the extraterritorial scope of American sanctions.

Recommendations for the UN mainly focused on unlocking key legal and diplomatic barriers. Participants called for a review of HTS’s designation under the 1267 regime, taking into account its public disavowal of ties to al-Qaeda and ongoing coordination against the Islamic State. The UN Special Envoy should be mandated to engage the new Syrian authorities to negotiate specific steps toward delisting or, at a minimum, time-bound exemptions aligned with transitional goals. Furthermore, the implementation of UNSCR 2664—which establishes humanitarian carve-outs across all UN sanctions regimes—should be actively promoted and incorporated into member state legislation to improve operational clarity and access for aid providers.

The workshop underscored the sobering reality that Syria’s future depends on concrete steps from the international community to ensure a successful political transition, economic recovery, and reconstruction. Maintaining rigid conditionality while under-delivering on aid and sanctions relief will neither foster inclusive governance nor prevent future conflict. Policymakers must realign their tools with the current realities—pairing cautious diplomacy with tangible economic support and giving civil society the space and resources to lead. As one participant put it, “sanctions might have been a tool to shape Syria’s future. Today, they are part of what’s preventing it.”

Photo: Ahmed Akacha

Reconstruction Aid, Not Sanctions Relief, is What Syria Really Needs

The price tag of Syrian reconstruction will be high, but Western governments can afford it.

Last week, the Biden administration issued General License 24, which removes prohibitions on a range of transactions with Syrian governing institutions, even while sanctions targeting Syrian entities and individuals remain in place. Syria’s newly appointed foreign minister, Asaad Al-Shaibani, welcomed the Biden administration’s move, but insisted that the US must lift all sanctions, which “constitute a barrier and an obstacle to the rapid recovery and development of the Syrian people.” The UN envoy for Syria, Geir Pedersen, has similarly called for “significant further efforts to adjust sanctions.” Meanwhile, German officials are reportedly discussing a plan that would see the EU ease sanctions on Syria so long as Syrian authorities implement political reforms.

These discussions on sanctions relief are important and reflect the urgency of such relief for Syria’s economic recovery. Syria is entangled in a web of US, EU, and UN sanctions. These measures include sanctions targeting the Syrian state and key economic sectors, which were imposed to weaken the Assad regime. Separate sanctions target Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a designated terrorist organization that comprises the core of the new Syrian leadership. But while determining a timeline and conditions for sanctions relief is important, Western officials and Syrian authorities are already sliding into a debate over what sanctions relief is warranted and at what stage. Meanwhile, Syrian civil society actors, cognizant of the precarious humanitarian situation in Syria, are being forced to use their political energy to advocate for sanctions relief, when the relief is not what truly matters for the stabilization of Syria.

The debate over sanctions relief risks becoming a distraction from the far more important aim of securing reconstruction aid. Syria is a country devastated by a brutal civil war. While sanctions exacerbated economic hardships in the country, contributing to currency devaluation, hyperinflation, and soaring budget deficits, the measures were significantly tightened only in 2019, at which point the Syrian economy had already effectively collapsed. In short, sanctions relief will not suffice to restore the Syrian economy.

The inadequacy of sanctions relief as both a political and economic goal becomes especially clear when considering what sanctions relief really entails. Sanctions are nothing more than language contained in laws and regulations. As such, lifting sanctions means nothing more than the creation of new legal language. While the imposition of sanctions does impose legal prohibitions that prevent governments or private sector actors from engaging in certain economic activities, lifting sanctions does not introduce any obligations for those actors to resume economic activities.

Clearly, sanctions relief cannot be the primary goal of advocacy. Removing legal prohibitions for economic engagement with Syria is very important, but it is a simply a means to an end. The goal of advocacy must be to push Western governments to take action that will really make a difference. What Syria needs is for Western governments to forthrightly commit to providing billions of dollars of reconstruction aid that can help resurrect the Syrian economy.

To this end, it is troubling is that Western governments have so far said little about their commitment to reconstruction in Syria. The recent visit of the German and French foreign ministers to Damascus was followed by headlines declaring that the EU would “will not fund new Islamist structures” rather than headlines committing European financing for reconstruction.

While European governments did provide Syria much-needed humanitarian aid during the long civil war, support for reconstruction will require a far greater political commitment. Not only is the scale of financial assistance required much larger, but the aid must be provided in parallel with what will surely be a complex political transition. The challenge of creating more inclusive political institutions in Syria may explain Western equivocation on the issue of reconstruction aid. But the reluctance to even signal the possibility that substantial aid could be forthcoming reflects a typical cynicism in Western capitals. To ensure that Syria secures both sanctions relief and the billions of dollars in aid, Syrian authorities and Syrian civil society must be unified in their calls for reconstruction support. There are several reasons why effective advocacy requires clear messaging that the paramount goal is reconstruction assistance, and not sanctions relief.

First, sanctions relief itself will not restore the Syrian economy, even if it is provided quickly. As Karam Shaar and Benjamin Fève have detailed, the economic situation in Syria is dire. The economy has contracted 80 percent since the onset of the civil war. Nine out of ten Syrians live below the poverty line. The damage to cities and infrastructure is extensive. A 2018 study used satellite imagery to identify over 100,000 damaged structures in Syria’s major cities, including thousands of homes destroyed by the Assad regime’s criminal use of barrel bombs on civilian targets. In this context, rebuilding Syria’s economy means replacing the capital stock while also restoring economic institutions and networks. A 2019 estimate on the costs of reconstruction put the figure as high as $400 billion. Given the scale of the devastation, post-conflict recovery in Syria is not something that can be accomplished through the resumption of private sector business activity. A resumption of trade and investment in Syria will certainly help stabilize the economy and improve the welfare of ordinary Syrians. But rebuilding critical infrastructure and restoring public services, actions necessary for Syria’s long term economic development, will require massive investments made by the Syrian state, with funds provided by foreign donors. This is precisely how Western governments have sought to support economic recovery in Ukraine, where the United States and EU have so far provided a combined $67 billion of financial support to the government. A similar commitment must be made for Syria.

Second, if sanctions relief is cast as the main goal of advocacy, Syrian stakeholders risk enabling Western governments to wash their hands of the responsibility to provide reconstruction assistance. We already see signs that Western governments will be content to provide sanctions relief so long as they can foist the responsibilities of reconstruction on other actors—the issuance of the General License 24 was quickly followed by the dispatch of Turkish and Qatari floating power plants to Syria. It was also no surprise that Al-Shaibani made his first overseas visit to Saudi Arabia, another potential reconstruction donor. Western governments should not leave Syrian authorities to seek reconstruction assistance from regional powers alone. Such an arrangement would give regional powers extraordinary influence over the course of the political transition in Syria. Western governments, meanwhile, will have little influence beyond the leverage provided by their remaining sanctions, and will therefore be inclined to keep those sanctions in place. While the US began to ease sanctions on Sudan in 2017, a paltry increase in aid contributed to Sudan’s slide into a deep economic crisis just one year later. The imposition of austerity measures by President Omar al-Bashir in 2018 spurred a new round of unrest, eventually triggering a new civil war. To avoid the same fate, Syria needs reconstruction support from a wide range of donor countries. This will ensure that the issue of reconstruction is not unduly politicized. Western policy must shift from the mindset of economic coercion to one of economic inducements.

Third, the best way to ensure that sanctions relief works is to ensure Western governments are committed to providing reconstruction aid. Providing effective sanctions relief is a complex process. Even if Western authorities issue new licenses or rollback sanctions designations altogether, the implementation of sanctions relief depends on proactive outreach by authorities to provide guidance and encourage economic operators to take advantage of the more permissive environment for trade and investment. Western governments have tended to take a lackadaisical approach to the provision of such guidance unless the lingering sanctions are preventing the implementation of their own policies. A cautionary tale can be seen in the aftermath of the 2016 peace deal between the Colombian government and FARC, a rebel group designated by the US as a foreign terrorist organization (the same designation that applies to HTS). The US supported the peace deal but provided limited aid for its implementation. The US aid program was mainly focused on supporting the Columbian government in implementation of the deal, rather than supporting reintegration of the FARC rebels into civilian life. This is partly why FARC was only removed from the FTO list in 2021, five years after its fighters had demobilized. Had US authorities been required to engage with FARC at an early stage because of their own policy commitments, there would have been greater urgency to remove the legal impediments to such engagement by any and all actors. Ultimately, the delay in providing sanctions relief jeopardized implementation of the peace deal.

Finally, there are certain kinds of aid and technical assistance that only Western governments can provide to Syria. For example, rebuilding Syria's economy will require reform of the banking sector, including through the implementation of anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing controls that give international banks and financial institutions confidence they can avail themselves of sanctions relief and transact with Syrian banks. If Western governments lift sanctions, but do not help Syrian banks improve their financial integrity, then the economic recovery will falter, largely due to overcompliance among private sector operators. Here, the cautionary tale is Iran, where the lifting of nuclear sanctions in 2016 led to a modest recovery in trade and investment. However, failure to support Iran's push to comply with critical financial crime regulations left Iranian banks unable to reintegrate with the global financial system. Foreign companies seeking to re-establish operations in Iran faced tremendous barriers as they struggled to conduct even routine banking operations. Unsurprisingly, foreign firms also struggled to secure financing for trade or investment deals. The failure to mobilize more investment into Iran left the nuclear deal vulnerable to domestic and foreign political opponents, and the deal effectively collapsed in 2018 following a unilateral US withdrawal.

If Syrian authorities and civil society demand that Western governments provide reconstruction assistance, they will benefit from sanctions relief. But if they allow the parameters of the debate to focus on sanctions relief alone, whatever relief and reconstruction support materializes will certainly prove insufficient. In this sense, Syrians must not only push Western governments to recognize their direct responsibility to redress the economic consequences of sanctions, but also the expediency of contributing to Syrian reconstruction generously and broadly. The price tag of Syrian reconstruction will be high, but Western governments can afford it. What no one can afford is to squander this historic opportunity to build a more prosperous, equitable, and resilient economy in Syria.

Photo: Ahmed Akacha

Sanctions, CBDCs, and the Role of ‘Decentral Banks’ in Bretton Woods III

In a world with two parallel financial systems, a country would not necessarily have a single reserve bank.

In a recent conversation on the Odd Lots podcast, Zoltan Pozsar offered an interesting use case for central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), a potentially transformative technology that 86 percent of central banks are “actively researching” according to a BIS survey from 2021.

Pozsar, a former Credit Suisse strategist who is setting up his own research outfit, believes that a new global monetary order is emerging—he calls it “Bretton Woods III.” As part of this order, the adoption of CBDCs will enable central banks to play a more pivotal role in global trade through the formation of a “state-to-state” network that is intended to be independent of Western financial centres and the dollar. In this network, central banks will play a “dealer” role when it comes to providing liquidity for trade among developing economies. Commenting on China’s push to internationalise the renminbi, Pozsar set out his vision:

You need to imagine a world where five, ten years from now we are going to have a renminbi that’s far more internationally used than today, but the settlement of international renminbi transactions are going to happen on the balance sheets of central banks. So instead of having a network of correspondent banks, we should be thinking about a network of correspondent central banks and a world where you have a number of different countries and in which each of those different countries have their banking systems using the local currency but when country A wants to trade with country B… The [foreign exchange] needs of those two local banking systems are going to be met by dealings between two central banks.

In short, Pozsar believes that the adoption of CBDCs will enable the creation of a “new correspondent banking system” built around central banks. But even if central banks do begin to use CBDCs to settle trade, reducing dependence on dollar liquidity and legacy correspondent banking channels, the underlying problem motivating CBDC adoption will remain.

Moving away from the dollar-based financial system is foremost about geopolitics. Globalisation, as we have known it, reinforced a unipolar order. The United States was able to leverage its unique position in the global economy into unrivalled superpower status. In the last two decades, the weaponisation of the dollar further augmented U.S. power—Americans are uniquely able to wage war without expending military resources, which is another kind of exorbitant privilege. As Pozsar notes, the countries moving fastest towards CBDCs are those that are either currently under a major U.S. sanctions program (Russia, Iran, Venezuela etc.) or at risk of being targeted (China, Pakistan, South Africa etc.) These countries recognise “that it is pointless to internationalise your currency through a Western financial system… and through the balance sheets of Western financial institutions when you basically do not control that network of institutions that your currency is running through.” As Edoardo Saravalle has argued, the power of U.S. sanctions is actually underpinned by the central role of the Federal Reserve in the global economy.

Adopting CBDCs would enable countries to reduce the proportion of their foreign exchange reserves held in dollars while also reducing reliance on U.S. banks and co-opted institutions such as SWIFT to settle cross-border payments. However, even if countries reduce their exposure to the dollar-based financial system in this way, U.S. authorities will still be able to use secondary sanctions to block central banks from the U.S. financial system for any transaction with a sanctioned sector, entity, or individual. Any financial institution still transacting with a designated central bank could likewise find itself designated.

Moreover, even if Bretton Woods III emerges, leading to the formation of a robust parallel financial system that is not based on the dollar, central banks will continue to engage with the legacy dollar-based financial system. It is difficult to image a central bank correspondent banking network in which nodes are not shared between the dollar-based and non-dollar based financial networks. As such, the threat of secondary sanctions or being placed on the FATF blacklist—moves that would cut a central banks access to key dollar-based facilities—will remain a significant threat.

Even Iran, which is under the strictest financial sanctions in the world, including multiple designations of its central bank, continues to depend on dollar liquidity provided through a special financial channel in Iraq. A significant portion of Iran’s imports of agricultural commodities continue to be purchased in dollars. Iran earns Iraqi dinars for exports of natural gas and electricity to its neighbour. The Iraqi dinars accrue at an account held at the Trade Bank of Iraq. The dinar is not useful for international trade, and so Iran converts its dinar-denominated reserves into dollars to purchase agricultural commodities—a waiver issued by the U.S. Department of State permits these transactions. The dollar liquidity is provided by J.P. Morgan, which plays a key role in the Trade Bank of Iraq’s global operations, having led the creation of the bank after the 2003 invasion.

The fact that the most sanctioned economy in the world depends on dollar liquidity for its most essential trade suggests that central banks will remain subject to U.S. economic coercion, owing to continued use of the dollar for at least some trade. But even in cases where Iran conducts trade without settling through the dollar, U.S. secondary sanctions loom large.

For over a decade, China has continued to purchase large volumes of Iranian oil in violation of U.S. sanctions, paying for the imports in renminbi. Iran is happy to accrue renminbi reserves because of its demand for Chinese manufactures. But owing to sanctions on Iran’s financial sector, Iranian banks have struggled to maintain correspondent banking relationships with Chinese counterparts. When the bottlenecks first emerged more than a decade ago, China tapped a little-known institution called Bank of Kunlun to be the policy bank for China-Iran trade.

The bank was eventually designated by the US Treasury Department in 2012. Since then, Bank of Kunlun has had no financial dealings with the United States, but that has not eased the bank’s transactions with Iran. Bank of Kunlun is owned by Chinese energy giant CNPC, an organisation with significant reliance on U.S. capital markets. When the Trump administration reimposed secondary sanctions on Iran in 2018, Bank of Kunlun informed its Iranian correspondents that it would only process payment orders or letters of trade in “humanitarian and non-sanctioned goods and services,” a move that was intended to forestall further pressure on CNPC. Ultimately, Bank of Kunlun had far less exposure to the U.S. financial system that China’s own central bank ever will, a fact that points to the limits of a central bank correspondent banking network. For CBDCs to serve as a defence against the weaponised dollar, they would need to be deployed by institutions that maintain no nexus with the dollar-based financial system. It is necessary to think beyond central banks.

What Pozsar has failed to consider is that in a world with two parallel financial systems, a country would not necessarily have a single reserve bank. Alongside central banks, we can envision the rise of what I call decentral banks. If a central bank is a monetary authority that is dependent on the dollar-backed financial system and settles foreign exchange transactions through the dollar, a decentral bank is a parallel authority that steers clear of the dollar-backed financial system and settles foreign exchange transactions through CBDCs. The extent to which Bretton Woods III really represents the emergence of a new bifurcated global monetary order depends not only on the adoption of CBDCs, but also the degree to which the innovations inherent in CBDCs enable countries to operate two or more reserve banks whose assets and liabilities are included in a consolidated sovereign balance sheet.

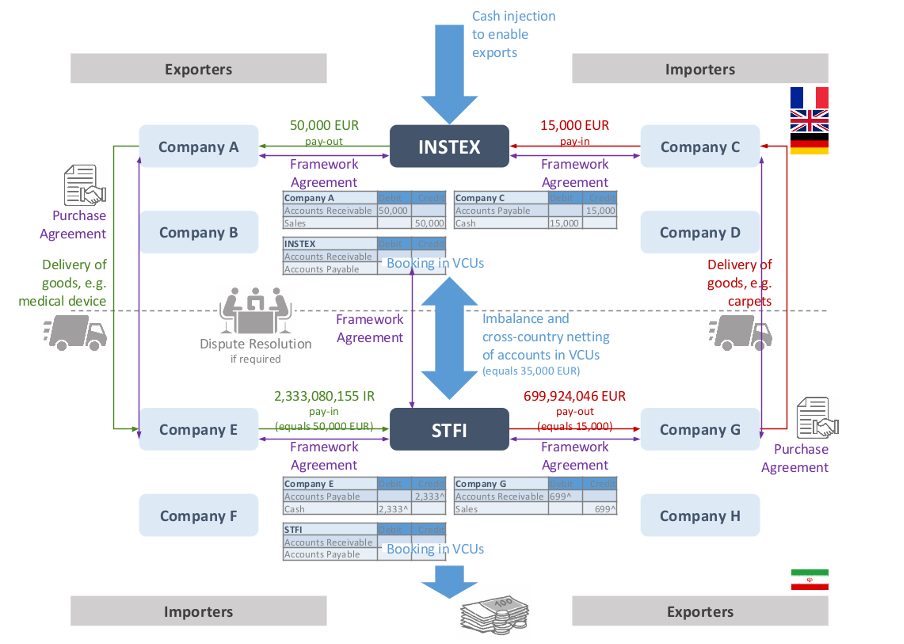

Again, Iran offers an interesting case study for what this innovation might look like. The reimposition of U.S. secondary sanctions on Iran in 2018 crippled bilateral trade between Europe and Iran. Conducting cross-border financial transactions was incredibly difficult owing to limited foreign exchange liquidity and the dependence on just a handful of correspondent banking relationships. France, Germany, and the United Kingdom took the step to establish INSTEX. As a state-owned company, INSTEX would work with its Iranian counterpart, STFI, to establish a new clearing mechanism for humanitarian and sanctions-exempt trade between Europe and Iran. The image below is taken from a 2019 presentation used by the management of INSTEX to explain how trade could be facilitated without cross-border financial transactions.

The model is strikingly like Pozsar’s suggestion that CBDCs will enable central banks to settle trades using their balance sheets, rather than relying on the liquidity of banks and correspondent banking relationships. INSTEX and STFI were supposed to net payments made by Iranian importers to European exporters with payments made by European importers to Iranian exporters, using a “virtual currency unit” to book the trade. The likely imbalances would be covered by a cash injection into INSTEX (Europe was exporting far more than it was importing after ending purchases of Iranian oil). It was an elegant solution, which sought to scale-up the methods being used by treasury managers at multinational companies operating in Iran to purchase inputs and repatriate profits.

Earlier this year, INSTEX was dissolved. Its shareholders, which eventually counted ten European states, lacked the political fortitude to see the project through. Notwithstanding bold claims about preserving European economic sovereignty in the face of unilateral American sanctions, there was always a sense among European officials that Iran was undeserving of a special purpose vehicle. But as the world moves to a new financial order, more institutions like INSTEX will emerge. Pozsar’s vision is bold insofar as he believes central banks will establish new cross-border clearing mechanisms based on CBDCs. But if new digital currencies can emerge to displace the dollar in the global monetary order, so too can new institutions be established.

Pozsar’s vision for Bretton Woods III becomes more convincing if one considers that the emergence of institutions such as decentral banks could lead to the creation of correspondent banking networks that are truly divorced from the dollar-based financial order. However, there remain plenty of reasons to doubt that such a system will emerge. Pozsar appears to have given little consideration to the issue of state capacity. Most countries have poorly managed central banks as it is—in the Odd Lots interview he pointed to Iran and Zimbabwe as early movers on CBDCs. We should have low expectations for the ability of most governments to develop and implement new technologies such as CBDCs or to establish wholly new institutions such as decentral banks. Moreover, the ability of the U.S. to use carrots and sticks to interfere with those efforts should not be underestimated.

There may be compelling structural drivers for something like Bretton Woods III, namely the rise of China and the overall shift in the global distribution of output. But somewhere along the way those structural drivers need to be converted into institutional processes. Bretton Woods is shorthand for the idea that monetary rules are as important for the operation of the global economy as the macroeconomic fundamentals. Countries reluctant to break the rules will struggle to rewrite them.

Photo: Canva