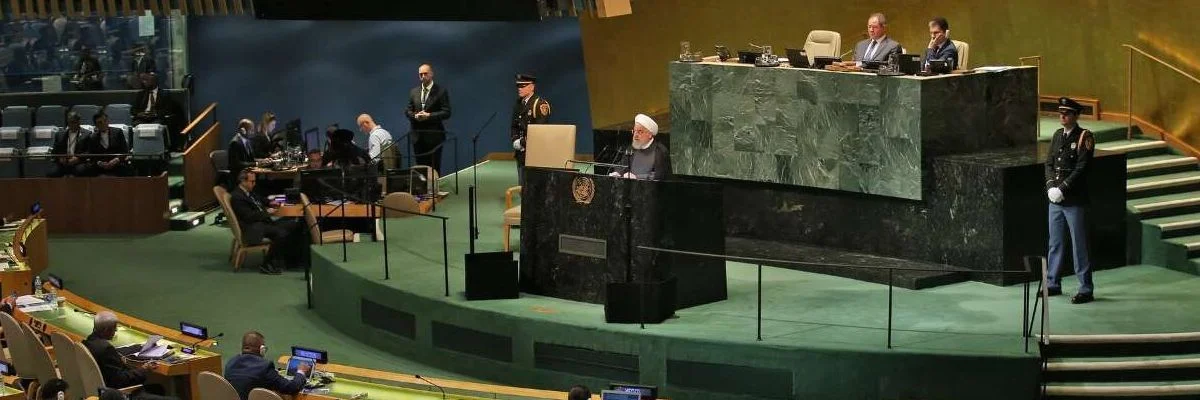

Full Remarks Made by the Iranian President at the United Nations

◢ The prepared remarks of Iranian President Hassan Rouhani delivered at the United Nations General Assembly on September 25, 2019. They are published here in full in the interest of providing fuller insight into Iran’s intended message on the potential for diplomacy with the United States.

Editor’s Note: The following are the prepared remarks of Iranian President Hassan Rouhani delivered at the United Nations General Assembly on September 25, 2019. The remarks, which have not been checked against delivery, were provided by the Permanent Mission of the Islamic Republic of Iran to the United Nations. They are published here in full in the interest of providing fuller insight into Iran’s intended message on the potential for diplomacy with the United States.

In the name of God, the Most Compassionate, the Most Merciful

Mr. President

I would like to congratulate your deserved election as the president of the seventy-fourth General Assembly of the United Nations and wish success and good luck for Your Excellency and the honorable Secretary General.

At the outset, I should like to commemorate the freedom-seeking movement of Hossein (PBUH) and pay homage to all the freedom-seekers of the world who do not bow to oppression and aggression and tolerate all the hardship of the struggle for rights, as well as to the spirits of all the oppressed martyrs of terrorist strikes and bombardment in Yemen, Syria, Occupied Palestine, Afghanistan and other countries of the world.

Ladies and Gentlemen

The Middle East is burning in the flames of war, bloodshed, aggression, occupation and religious and sectarian fanaticism and extremism; And under such circumstances, the suppressed people of Palestine are the biggest victim. Discrimination, appropriation of lands, settlement expansions and killings continue to be practiced against the Palestinians.

The US and Zionist imposed plans such as the deal of century, recognizing Beit-ul Moqaddas as the capital of the Zionist regime and the accession of the Syrian Golan to other occupied territories are doomed.

As against the US destructive plans, the Islamic Republic of Iran’s regional and international assistance and cooperation on security and counter-terrorism have been so much decisive. The clear example of such an approach is our cooperation with Russia and Turkey within the Astana format on the Syrian crisis and our peace proposal for Yemen in view of our active cooperation with the special envoys of the Secretary General of the United Nations as well as our efforts to facilitate reconciliation talks among the Yemen parties which resulted in the conclusion of the Stockholm peace accord on HodaydaPort.

Distinguished Participants

I hail from a country that has resisted the most merciless economic terrorism, and has defended its right to independence and science and technology development. The US government, while imposing extraterritorial sanctions and threats against other nations, has made a lot of efforts to deprive Iran from the advantages of participating in the global economy, and has resorted to international piracy by misusing the international banking system.

We Iranians have been the pioneer of freedom-seeking movements in the region, while seeking peace and progress for our nation as well as neighbors; and we have never surrendered to foreign aggression and imposition.We cannot believe the invitation to negotiation of people who claim to have applied the harshest sanctions of history against the dignity and prosperity of our nation. How someone can believe that the silent killing of a great nation and pressure on the life of 83 million Iranians arewelcomed by the American government officials who pride themselves on such pressures and exploit sanctionsin an addictive manner against a spectrum of countries such as Iran, Venezuela, Cuba, China and Russia. The Iranian nation will never ever forget and forgive these crimes and criminals.

Ladies and Gentlemen

The attitude of the incumbent US government towards the nuclear deal or the JCPOA not only violates the provisions of the UN Security Council Resolution 2231, but also constitutes a breach of the sovereignty and political and economic independence of all the world countries.

In spite of the American withdrawal from the JCPOA, and for one year, Iran remained fully faithful to all its nuclear commitments in accordance with the JCPOA. Out of respect for the Security Council resolution, we providedEurope with the opportunity to fulfill its 11 commitments made to compensate the US withdrawal. However, unfortunately, we only heard beautiful words while witnessing no effective measure. It has now become clear for all that the United States turns back to its commitments and Europe is unable and incapable of fulfilling its commitments. We even adopted a step-by-step approach in implementing paragraphs 26 and 36 of the JCPOA. And we remain committed to our promises in the deal. However, our patience has a limit; When the US does not respect the United Nations Security Council, and when Europe displays inability, the only way shall be to rely on national dignity, pride and strength. They call us to negotiation while they run away from treaties and deals. We negotiated with the incumbent US government on the 5+1 negotiating table; however, they failed to honor the commitment made by their predecessor.

On behalf of my nation and state, I would like to announce that our response to any negotiation under sanctions is negative. The government and people of Iran have remained steadfast against the harshest sanctions in the past one and a half years ago and will never negotiate with an enemy that seeks to make Iran surrender with the weapon of poverty, pressure and sanction.

If you require a positive answer, and as declared by the leader of the Islamic Revolution, the only way for talks to begin is return to commitments and compliance.

If you are sensitive to the name of the JCPOA, well, then you can return to its framework and abide by the UN Security Council Resolution 2231. Stop the sanctions so as to open the way for the start of negotiations.

I would like to make it crystal clear: If you are satisfied with the minimums, we will also convince ourselves with the minimums; either for you or for us. However, if you require more, you should also pay more.

If you stand on your word that you only have one demandfor Iran i.e. non-production and non-utilization of nuclearweapons, then it could easily be attained in view of the IAEA supervision and more importantly, with the fatwa of the Iranian leader. Instead of show of negotiation, you shall return to the reality of negotiation. Memorial photo is the last station of negotiation not the first one.

We in Iran, despite all the obstructions created by the US government, are keeping on the path of economic and social growth and prosperity. Iran’s economy in 2017, registered the highest economic growth rate in the world. And today, despite fluctuations emanating from foreign interference in the past one and a half years, we have returned to the track of growth and stability. Iran’s gross domestic product minus oil has become positive again in recent months. And the trade balance of the country remains positive.

Distinguished Participants

The security doctrine of the Islamic Republic of Iran is based on the maintenance of peace and stability in the Persian Gulf and providing freedom of navigation and safety of movement in the Strait of Hurmoz. Recentincidents have seriously endangered such security. Security and peace in the Persian Gulf, Sea of Oman and the Strait of Hormuz could be provided with the participation of the countries of the region and the free flow of oil and other energy resources could be guaranteed provided that we consider security as an umbrella in all areas for all the countries.

Upon the historical responsibility of my country in maintaining security, peace, stability and progress in the Persian Gulf region and Strait of Hormuz, I should like to invite all the countries directly affected by the developments in the Persian Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz to the Coalition for Hope meaning Hormuz Peace Endeavor.

The goal of the Coalition for Hope is to promote peace, stability, progress and welfare for all the residents of the Strait of Hormuz region and enhance mutual understanding and peaceful and friendly relations amongst them.

This initiative includes various venues for cooperation such as the collective supply of energy security, freedom of navigation and free transfer of oil and other resources to and from the Strait of Hormuz and beyond.

The Coalition for Hope is based on important principles such as compliance with the goals and principles of the United Nations, mutual respect, equal footing, dialog and understanding, respect to territorial integrity and sovereignty, inviolability of international borders, peaceful settlement of all differences, rejection of threat or resort to force and more importantly two fundamental principles of non-aggression and non-interference in the domestic affairs of each other. The presence of the United Nations seems necessary for the creation of an international umbrella in support of the Coalition for Hope.

The Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Islamic Republic of Iran shall provide more details of the Coalition for Hope to the beneficiary states.

Ladies and Gentlemen

The formation of any security coalition and initiative under any title in the region with the centrality and command of foreign forces is a clear example of interference in the affairs of the region. The securitization of navigation is in contravention of the right to free navigation and the right to development and wouldescalate tension, and more complication of conditions and increase of mistrust in the region while jeopardizing regional peace, security and stability.

The security of the region shall be provided when American troops pull out. Security shall not be supplied with American weapons and intervention. The United States, after 18 years, has failed to reduce acts of terrorism; However, the Islamic Republic of Iran, managed to terminate the scourge of Daesh with the assistance of neighboring nations and governments. The ultimate way towards peace and security in the Middle East passes through inward democracy and outward diplomacy. Security cannot be purchased or supplied by foreign governments.

The peace, security and independence of our neighbors are the peace, security and independence of us. America is not our neighbor. This is the Islamic Republic of Iran which neighbors you and we have been long taught that: Neighbor comes first, then comes the house. In the event of an incident, you and we shall remain alone. We are neighbors with each other and not with the United States.

The United States is located here, not in the Middle East. The United States is not the advocate of any nation; neither is it the guardian of any state. In fact, states do not delegate power of attorney to other states and do not give custodianship to others. If the flames of the fire of Yemen have spread today to Hijaz, the warmonger should be searched and punished; rather than leveling allegations and grudge against the innocence. The security of Saudi Arabia shall be guaranteed with the termination of aggression to Yemen rather than by inviting foreigners. We are ready to spend our national strength and regional credibility and international authority.

The solution for peace in the Arabian Peninsula, security in the Persian Gulf and stability in the Middle East should be sought inside the region rather than outside of it. The issues of the region are bigger and more important than the United States is able to resolve them. The United States has failed to resolve the issue in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria, and has been the supporter of extremism, Talibanism and Daeshism. Such a government is clearly unable to resolve more sophisticated issues.

Distinguished Colleagues

Our region is on the edge of collapse, as a single blunder can fuel a big fire. We shall not tolerate the provocative intervention of foreigners. We shall respond decisively and strongly to any sort of transgression to and violation of our security and territorial integrity. However, the alternative and proper solution for us is to strengthen consolidation among all the nations with common interests in the Persian Gulf and the Hormuz region.

This is the message of the Iranian nation:

Let’s invest on hope towards a better future rather than in war and violence. Let’s return to justice; to peace; to law, commitment and treaty and the negotiating table. Let’s come back to the United Nations.

Photo: IRNA

Iran's Economy is Bruised, But Not Broken

◢ New data indicate that, while Donald Trump’s policy of “maximum pressure” has reduced Iranian oil exports to near zero and seriously hurt Iran’s economy, it has not caused anything resembling economic collapse. Furthermore, these data suggest that the economy is not in a steep decline, one that would anytime soon force Iran to capitulate.

This article was originally published in Lobelog.

Last April, in a column for this blog I predicted that sanctions are very unlikely to force Iran to renegotiate the multilateral nuclear deal known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). In particular, I argued that the belief held by Iran hawks in Washington foreign policy circles, that economic pressure will eventually force Iran to the negotiating table, exaggerated the importance of oil exports for Iran’s economy.

New data indicate that, while Donald Trump’s policy of “maximum pressure” has reduced Iranian oil exports to near zero and seriously hurt Iran’s economy, it has not caused anything resembling economic collapse. Furthermore, these data suggest that the economy is not in a steep decline, one that would anytime soon force Iran to capitulate.

The national accounts data, published by the Statistical Center of Iran (SCI), indicate that, in the Iranian year 2018/19 (21 March 2018 to 20 March 2019), GDP declined by 4.9 percent, which is far from a collapse of output. Coming after two years of robust growth following the July 2015 nuclear deal, it puts the economy still above its 2015 level.

This decline was, not surprisingly, led by the oil sector, which fell by 14 percent, followed by manufacturing (6.5 percent), which depends on imports of parts, and construction (4.5 percent). However, non-oil GDP, which measures the level of domestic economic activity, fell by only 2.4 percent. This is because output in services, which accounts for 55 percent of Iran’s non-oil GDP, remained unchanged, and agriculture, accounting for another 10 percent, fell by 1.5 percent.

Iran’s economy has taken a beating, but it is not a disaster, as President Trump likes to describe it. To most Iranians, his remarks last September—which he repeated in June—that Iranians “can’t buy bread,” showed how out of touch he is with the consequences of his own policy. Travelers to Iran have noticed, as I did this summer, that supermarkets shelves were full (though mostly with home produced goods at high prices), and there were no lines in government distribution centers, which are the hallmark of real disaster economies, like Venezuela.

High prices, triggered by the tripling in the value of the U.S. dollar since early 2018, have taken their toll on household incomes. The most recent SCI survey of income and expenditures shows that in 2018/19 average real incomes per capita fell by 6.7 percent in urban areas and 9.1 percent in rural areas, more than the decline in GDP per capita. These are sharp drops, but obviously not enough to ignite urban protests, as the Trump administration had hoped.

Going forward, the question is whether the Iranian economy is on a steep decline, is stabilizing at a lower level, or is on the road to recovery. This will influence Iran’s willingness, or lack thereof, to negotiate with the U.S., and should matter for Washington as it evaluates its Iran policy in light of its failure so far to yield the desired results. As always, Iran hawks recommend staying the course with “maximum pressure,” believing that Iran will “ultimately do a 180 if they perceive that there’s no way out.”

But what if there is a way out? What if Iran can restructure its economy to become less dependent on imports and truck along with reduced oil exports? Iranian leaders may be pinning their hopes on this scenario and thinking that the worst is over when they flatly reject negotiations.

In this belief they can draw support from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In its April 2019 World Economic Outlook, the IMF predicted that negative economic growth in Iran will end in 2020 and positive growth of around 1 percent per year will prevail till 2024. Not a rosy scenario by any means, as it implies loss of economic growth and declining per capita incomes for the foreseeable future, but it may be enough to convince Iranian leaders not to capitulate.

IMF forecasts beyond a year do not always materialize, and we do not know their assumptions about when U.S. sanctions will end. But the latest evidence from Iran’s labor force survey suggests that an end to the recession may be in sight. They show that in spring 2019, compared to spring 2018 before sanctions came back in full force, employment increased by 324,000 and the number unemployed fell by 365,000. As a result, the unemployment rate fell to a five-year low of 10.8 percent.

Significantly, half of this increase in employment was in industry, the sector that is most exposed to sanctions because its production depends on imports of intermediate inputs. Nearly half of all Iranian imports are intermediate goods.

Cynics have reason to doubt official Iranian surveys, but the rise in employment reported by the SCI makes good economic sense. For over a year, Iran’s currency has been at a historic low and its labor costs the cheapest in memory (about $5 per day for unskilled labor, half that in China). With rising profitability, it makes perfect sense for businesses to increase hiring to fill in for lost imports.

But the switch to local production faces two obstacles. First, the U.S. sanctions themselves. To sustain the structural adjustment needed to reconfigure industrial production requires access to global markets, which trade sanctions inhibit. Second, it requires a banking system to finance businesses to restructure. Iran’s banking system is too weak to do so at present.

While the prospects of economic recovery remain uncertain, it is safe to reject the assumption that Iran’s economy is on a “death spiral,” to use a favorite phrase of Iran hawks. While economic conditions are desperate for many Iranians in need of jobs and medicine, they are not desperate enough for Iran’s leaders to risk getting into a costly war with their southern neighbors and the U.S. just to end the current stalemate. Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who has ruled out negotiations with Trump, is for one interested in finding out if the economy will rise to the challenge of sanctions and thus become the “resistance economy” that he has advocated for years.

Photo: IRNA

No, China Isn't Giving Iran $400 Billion

◢ A recent report from the London-based publication Petroleum Economist offers a cautionary tale of “fake news.” The claim that China will extend a $400 billion credit line to Iran is poorly sourced and inconsistent with both recent trends in China-Iran trade and the scope of China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

A recent report from the London-based publication Petroleum Economist offers a cautionary tale of “fake news” having spurred an unprecedented debate in about Sino-Iranian relations.

Quoting an anonymous senior source “closely connected” to Iran’s petroleum ministry, the article claims the existence of a major new agreement between Tehran and Beijing that could reflect “a potentially material shift to the global balance of the oil and gas sector.” The figures presented to back up this claim are astronomical—China will invest a total of $400 billion in Iran over the next 5 years, split between $280 billion in the development of Iran’s energy sector and $120 billion for infrastructure projects. This first round of investments is claimed to be part of a 25-year plan with capital injected in the Iranian economy every five years. Despite the attention that the report garnered, with follow-up articles in Forbes and Al Monitor among other publications, Petroleum Economist’s figures do not appear plausible.

China and Iran signed a comprehensive strategic partnership, the highest level in the hierarchy of Beijing’s partnership diplomacy, in 2016. On the occasion, Xi Jinping and Hassan Rouhani signed a comprehensive 25-year deal which included a series of multi-sector agreements intended to boost bilateral trade to $600 billion within a decade. Even considering the potential for trade following the listing of international sanctions after the implementation of the JCPOA, the goal was extremely ambitious, if not totally unrealistic.

Indeed, the re-imposition of US secondary sanctions in November 2018 has deeply impacted the level of China-Iran trade. As detailed in a Bourse & Bazaar special report, in the last trimester of 2018 Chinese exports to Iran dropped by nearly 70 percent, falling from the already low figure of $1.2 billion in October to a dramatic low of $400 million in December. Exports to Iran have now stabilized at just under $1billion each month.

Meanwhile, the flow of crude oil from Tehran to Beijing—undoubtedly the engine of Sino-Iranian trade—suffered a major slowdown due to the revocation of US oil waivers expired in May 2019. Despite China continuing buying Iranian oil in defiance of US sanctions, using ship-to-ship transfers and ghost tankers, the level of imports remain about half of pre-sanctions levels.

Post-November 2018 trade figures show a clear picture. Although China remains Iran’s most important foreign partner, Beijing has adopted a mixed policy vis-à-vis US sanctions—certainly bolder than European states, but still cautious. In short, the pattern of China-Iran trade suggests that a five-year, three-digit investment program is not credible, especially with oil imports at their minimum, secondary sanctions in place, and the poor record for project delivery of Chinese infrastructure projects in Iran. Moreover, it is unrealistic that Iran’s suffering economy could absorb such a massive injection of capital.

Petroleum Economist’s figures look even less realistic if looked from a broader perspective. According to Morgan Stanley, the total Chinese investment in the Belt and Road Initiative could reach $1.2-1.3 trillion in 2027. In May 2017, Ning Jizhe, the vice-chairman of China’s National Development and Reform Commission (CNDR), declared that Beijing’s investments in the BRI for the following five years (2017-2022) were expected to be between $600 billion and $800 billion. Therefore, it is hard to believe that China will invest almost the equivalent of two-thirds of its planned budget for its most ambitious and largest foreign project in Iran alone. If the Chinese were indeed set to spend $400 billion on Iran, the recent French proposal to extend a $15 billion credit line to restore JCPOA’s economic benefits would be completely useless given Chinese largesse.

The anonymous source painted an idealistic picture for Petroleum Economist, claiming that China has agreed to keep increasing its import of Iran’s oil in defiance of the United States and “to put up the pace on its development” of Phase 11 of South Pars gas field—which, ironically, represents one the clearest examples of Beijing’s difficulties in delivering its projects.

Most perplexingly, the source claimed that the deal “will include up to 5000 Chinese security personnel on the ground in Iran to protect Chinese projects.” Such a claim directly contradicts Beijing’s strategy of remaining disengaged from the Persian Gulf, especially considering the current tensions. Indeed, China’s apolitical approach to the region and good relations with Saudi Arabia and the UAE—with which China has comprehensive strategic partnerships—would be severely undermined by the presence of a Chinese armed contingent on the ground in Iran. The presence of foreign troops is also a political impossibility in Iran, where the refueling of Russian bombers at an Iranian airbase caused a political scandal last year.

With the exception of a Fars News piece quoted by Middle East Monitor, practically no Iranian nor Chinese official and semi-official news outlet have reported or confirmed the figures presented by Petroleum Economist. State news agency IRNA, which launched its Chinese channel only days before the news came out, had no corroborating report. When asked, Iran’s oil minister Bijan Zanganeh denied rumors about the $400 billion investment plan, succinctly stating: “I have not heard such a thing.” The head of the Iran-China Chamber of Commerce called the reports “a joke” and urged people to be more careful about the news they share.

The figures quoted by Petroleum Economist do not accurately reflect the future of Chinese investment in Iran. Nevertheless, the news achieved what could be assumed to be its original goal— to bait clicks.

No doubt, Iran is trying to put some pressure on the West, and perhaps on China itself, by reinforcing the idea of a strong, growing, and unique relationship between Tehran and Beijing. It should also be noted that before his trip to China at the end of August, Iran’s foreign minister, Javad Zarif published an op-ed in Global Times—a practice that is typical of Xi Jinping—calling, with quite unprecedented audacity, for a new phase in Sino-Iranian relations.

However, ties between Iran and China should not be overestimated and deserve careful consideration. In the short-term, Beijing represents Iran’s minimum insurance against US sanctions; in the long-term Tehran may be forced to more expansive eastward shift. But this will happen at the pace of China’s “strategic patience,” and there will be no $400 billion bonanza.

Photo: IRNA

Here’s What the French Proposal for Trump and Iran Actually Entails

◢ A new report in the Daily Beast claims that Trump is flirting with a “$15 billion bailout for Iran.” But the mechanics of the proposal Trump is considering, put forward by French President Emmanuel Macron, are far more limited and reasonable than this and other reports have suggested.

A new report in the Daily Beast exclaims that Trump is flirting with a “$15 billion bailout for Iran.” But the mechanics of the proposal Trump is considering, put forward by French President Emmanuel Macron, are far more limited and reasonable than this and other reports may have you believe. What is being deliberated is a plan that does nothing more than restore Iran economic benefits it was already receiving under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), until Trump withdrew from the agreement, reinstating U.S. secondary sanctions.

Back in 2017, French, Italian, and Spanish refiners were importing around 600,000 bpd of Iranian oil on an annual basis. When the U.S. reimposed sanctions on Iran in November of 2018, it provided waivers for eight of Iran’s oil customers to sustain their imports at limited volumes. Italy was the only European customer to receive a waiver, but given the complicated nature of U.S. sanctions, the waiver itself was insufficient to give Italian state oil company ENI enough comfort to continue buying Iranian oil.

Eventually, in May of 2019, the oil waivers were fully eliminated, causing Iran’s oil exports to plummet further. Only China and Syria continue to buy Iranian oil in defiance of US sanctions. The cessation of European imports of Iranian oil has been the single greatest source of frustration for Iranian policymakers, who feel that Europe is failing to keep up its end of the bargain under the JCPOA nuclear deal. Iran imports a large volume of machinery and medicines from Europe—the loss of euro denominated revenues makes it much harder and more expensive for Iran to sustain these crucial imports, putting a strain on the Iranian economy.

In the face of these challenges, Europe established INSTEX, a state owned trade intermediary that would allow trade in non-sanctioned goods to flow without the need for cross-border financial transactions, and by extension, Iranian use of its now precious reserves of euros. But INSTEX has been hampered by the fact that it offers Iran no solution to sustain its oil sales to Europe. Not only is Iran ceding market share, but in its current form INSTEX will be unable to facilitate the billions of euros worth of imports from Europe that are currently left vulnerable without Iranian oil being sold to Europe in tandem.

This is the problem the French proposal seeks to solve. It is basically a riff on a proposal first put forward by the Iranians. The Iranians argued that if Europe is unable to purchase Iranian oil due to the reticence of European tanker companies and refiners to handle the crude, then Iran should “pre-sell” oil to Europe. Iran would be provided a line of credit today guaranteed against future oil sales to Europe to be completed when sanctions relief allows.

The figure that has been associated with the French plan—$15 billion—is a direct reflection of what it would take for Europe to restore the financial component of their oil purchases under the JCPOA. Over the course of a year, the value of 700,000 bpd in oil exports at a price of $58 per barrel is approximately $15 billion dollars. For context, in 2017, Europe imported 29,035,298 metric tonnes of crude oil, which is the equivalent of approximately 583,092 bpd. At the then still low oil prices, the value of those imports was just over EUR 10 billion. Accounting for a higher oil price and the need for round numbers, a $15 billion commitment is reflective of a normal state of affairs for European purchases of Iranian oil.

In short, the French are not aiming to provide any new money to Iran. Their plan is designed to provide Iran a financial benefit it was already receiving—in accordance with US sanctions relief—back in 2017. In this sense, the French are merely seeking permission from the Trump administration to restore their own compliance with the implementation of economic benefits of the JCPOA—a request growing more urgent as Iran loosens its own compliance with its nuclear commitments under the deal.

In some respects it is surprising that the French would embrace this plan given their relatively tepid push to sustain the economic benefits of the deal for Iran to date. But it would appear that President Macron believes a more substantial move is necessary to bring about a “ceasefire” in the economic war waged by Trump, and the Iranian escalations being pursued in response.

Crucially, the French plan does not call upon the U.S. to lend a single cent to Iran. The reason the Macron has appealed to Trump reflects both the political reality that he needs to de-escalate tensions between the U.S. and Iran as well as the practical reality that Europe is unable to provide the envisioned financial support without a sanctions waiver from the Treasury Department, either for the credit line itself, or for resumed oil sales.

The creation of new credit facilities for Iran was actually first considered in the summer of 2018 prior to the creation of INSTEX. European central banks were asked to consider opening a direct financial channel to Iran’s central bank to ease payment difficulties and enable the provision of export credit. But the central banks balked at the idea, both because Iran has yet to fully implement the financial crime regulations required by its FATF action plan (reforms which have still not been fully implemented) and also because of concerns about U.S. retaliation. Close advisors to the Trump administration were publicly calling for European central bankers to be sanctioned if such faculties were extended to Iran.

So some consent from the U.S. will be required to operationalized the French proposal. That may irk the Iranians, but it also makes the plan more feasible. European and Iranian policy makers alike have been disabused of the idea that direct defiance of U.S. sanctions is possible for France and the other EU member states. Macron has therefore decided to try and coax Trump towards a negotiated solution, dangling in front of him the prospect of talks with Iranian President Hassan Rouhani.

But importantly, the U.S. would be making a minimal concession to secure such talks. Any waiver granted to the Europeans could be revoked and the financial benefit Iran would receive is only part of the full financial benefits they were receiving prior to Trump’s withdrawal from the JCPOA and the reimposition of U.S. secondary sanctions.

Photo: Wikicommons

With Bolton Gone, Iran Must Seize Opportunity for De-Escalation

◢ John Bolton doggedly pursued maximum pressure, pushing aside the concerns expressed the secretary of state, secretary of treasury, military leaders and intelligence officials alike. While Trump’s antagonism towards the Iran nuclear deal predates his appointment of Bolton, the transformation of the Trump administration’s Iran policy into one of “economic war” was nonetheless dependent on Bolton’s ideological fixations.

The news that Trump has fired John Bolton—though the former national security advisor insists he resigned—will be well received in Tehran. Iranian foreign minister Javad Zarif had taken to branding Bolton as a member of the “B-Team”—alongside Israel’s Bibi Netanyahu, Saudi Arabia’s Mohammad bin Salman, and the UAE’s Mohammad bin Zayed—as a group that had been gunning for war in the Middle East. Iranian officials saw Bolton as a spoiler for diplomacy, a perception borne out by reporting on his role shaping and sharpening the Trump administration’s Iran policy over the last year.

Bolton’s ouster represents a real opportunity for the Trump administration to walk back from maximum pressure as more pragmatic officials outside the NSC find the space to assert their views once more. Despite the active roles played by the State Department’s Iran envoy, Brian Hook, and the Treasury Department’s undersecretary for terrorism and financial intelligence, Sigal Mandelker, in pushing forward the administration’s uncompromising messaging on Iran, the maximum pressure policy developed because Bolton was able to leverage his unique access to the president. Over the last year, Bolton repeatedly used this access to push the administration’s policy towards the extreme.

In March, Bolton and Pompeo were at loggerheads as to whether the Trump administration should revoke waivers permitting eight countries to continue to purchase Iranian oil on the condition that revenues were paid into tightly controlled escrow accounts. Bolton eventually prevailed. The revocation of the oil waivers in May led to insecurity in the Persian Gulf as Iran threatened the passage of maritime traffic through the Strait of Hormuz in retaliation for the restrictions on their oil exports.

In April, the Trump administration designated the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), part of Iran’s armed forces, a “Foreign Terrorist Organization,” in a move that had been debated by administration officials since late 2017, when the U.S. imposed a similar if less severe designation on the IRGC. Once again, Bolton was the key voice in favor of the move, despite the warnings of military and intelligence leaders that such a designation could make American troops in Iraq and Syria targets for retaliation.

In July, Bolton’s NSC advocated the revocation of the waivers which permit civil nuclear cooperation projects critical for the implementation of the JPCOA. European officials feared that the revocation of the waivers would effectively kill the nuclear deal. Trump eventually sided with Treasury Sectretary Steve Mnuchin who argued in favor of renewal, allowing the JCPOA to limp along.

Later that month, the Trump administration took the unprecedented step of sanctioning Zarif, despite reports earlier in the month that objections from Mnuchin and Pompeo had staved the move, strongly advocated by Bolton, to designate Iran’s foreign minister. The eventual designation caused an outcry in Iran, uniting figures across the political spectrum in condemnation of the U.S..

At each step Bolton doggedly pursued maximum pressure, pushing aside the concerns expressed the secretary of state, secretary of treasury, military leaders and intelligence officials alike. While Trump’s antagonism towards the Iran nuclear deal predates his appointment of Bolton, the transformation of the Trump administration’s Iran policy into one of “economic war” was nonetheless dependent on Bolton’s ideological fixations and mastery of the interagency process, qualities of which he has bragged.

Earlier this summer, several U.S. officials relayed to me their concern that the Trump administration’s Iran policy increasingly consisted of steps that created political costs for the United States—straining relationships with allies in Europe while deepening rifts with adversaries like China—while adding little meaningful economic pressure on Iran. The departure of Bolton may come as a relief to many of the career officials in the State and Treasury Departments who felt a growing incoherence—and their own irrelevance—in the administration’s policy.

It is certainly possible that President Trump will name another hawk to the role—there is no shortage of national security professionals in Washington wary of Iranian power—but it is highly unlikely that the replacement will have such a strong fixation on maximum pressure for its own sake. It is also unlikely that the new national security advisor will be as effective as John Bolton in working the bureaucratic machine of the White House.

In the hours following Bolton’s departure, Mnuchin insisted that the administration will maintain its maximum pressure campaign on Iran. But the need for that insistence is itself reflective of the opportunity now presented for the administration to slowly rollback aspects of its maximum pressure campaign and for Iran to offer the Trump administration a credible path to de-escalation.

With Bolton out, the prospects of direct talks between the US and Iran on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly later this month have certainly improved—Trump repeated his interest in meeting Iranian president Hassan Rouhani the same day he fired Bolton. But even if that remains a bridge too far for the Rouhani administration, who may consider it too risky to negotiate Trump in a moment of flux, there are more practical gains to be had. The simple restoration of the oil waivers, perhaps in accordance with the proposal advanced by French president Emmanuel Macron, could see Iran cease the resumption of uranium enrichment activities as part of its reduced compliance with the JCPOA.

Iran’s political predicament and economic pains are not John Bolton’s fault. But Bolton consistently pushed U.S. policy in directions that were perceived by Iranians as “war by other means.” Over the last few months, Iran has responded in kind. Bolton’s departure therefore is a useful reminder that while conflict may have structural roots—it is only as inevitable as the selection of a warmonger as national security advisor.

Photo: Wikicommons

India’s Iran Port Plans Languish Despite US Waiver

◢ Trump may have exempted Iran’s Chabahar port from sanctions, but India has struggled to realize its ambitions for the major infrastructure project. Recent government data confirms that no Indian investment has been made in the port in two years. As one Indian official involved with the project since its origins put it, “This was not what we hoped to achieve. Chabahar is only about photo-ops now, not substance.”

A year has passed since the US reimposed sanctions on Iran. During this time, the Trump administration exempted India’s investments in the Iranian port of Chabahar from sanctions in order to protect India’s strategic interests. Despite this accommodation, recent government data suggests that no new Indian investments have been made in the port project in the last two years.

Foreign aid expenditure figures released in July by the re-elected Modi government show that India has not spent any of its allocated funds for Chabahar since 2017. There is a conspicuous absence of spending even though roughly USD 20 million (150 crore rupees) was set aside each year. The government has now allocated a significantly lower, and perhaps more realistic, USD 6 million for the current year.

These figures confirm reports that India’s ambitions for Chabahar had hit a stumbling block even before Trump withdrew from the JCPOA nuclear deal. Evidently, the sanctions waiver has not been of much use either.

India’s Chabahar Ambitions

Indian prime minister Narendra Modi, now in his second term, has declared regional connectivity as a primary foreign policy goal and injected momentum into major initiatives to India’s east and west. A part of this was certainly driven by the state’s concerns about China’s own mammoth connectivity drive—the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—that runs through its immediate neighborhood and traditional sphere of influence. The project ideas themselves, however, pre-date the BRI.

The main regional connectivity project to India’s west is the Iran-India-Afghanistan transit initiative that hinges on the development of the Chabahar port along with road and rail links connecting it to Afghanistan. With Pakistan denying land access to India, New Delhi intends to use Chabahar to engage with the Afghan market and support Afghanistan’s trade and economic development.

Four years after Modi injected fresh momentum into the project, development at Chabahar has been slow—largely owing to US sanctions against Iran.

As per Iran’s original four-phase development plan, India was to invest USD 85 million to upgrade, equip, and operate two terminals on a ten-year lease. Indian prime minister Narendra Modi and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani oversaw the signing of this contract in May 2016 during the former’s visit to Iran.

Subsequently, Iran upgraded existing port infrastructure as per their agreed first phase of development. This upgraded port was inaugurated in December 2017 with great fanfare. The following year, India took over operations of the port but not much else went according to plan.

Ambitions vs. Reality

When it comes to sanctions, talk is never cheap.

Statements are more than enough to spook companies, heighten risk-aversion, and add further costs to proposed ventures. This was the case for Chabahar as early as Trump’s election campaign, long before the US president violated the nuclear deal.

The Indians first faced an investment chill at home. The Chabahar project calls for a private Indian firm to come on board as a strategic partner to manage, operate and maintain the port for ten years. The government entity created to oversee India’s foreign port projects—India Global Ports Limited (IGPL)—held two bidding rounds since 2016 with no result. It is now rewriting the terms a third time. Given the delay, the Indians signed on an Iranian firm (Kaveh Port and Marine Services) in the interim to take over operations.

A second task was to equip the port. European firms were Iran’s first preference but predictably after Trump’s win, they showed little-to-no interest in equipment bids. This left India with no choice but to work with Chinese firms. Interestingly, a Chinese company that won a bid to supply cranes in 2017 is blacklisted within India. Recent reports in the Indian media now suggest that some of these companies are reluctant to deliver equipment. Again, an environment of fear and uncertainty remains despite the US exemption.

A third aspect is the larger regional project on connectivity between India, Iran, and Afghanistan. As things stand, all parties are working with existing port infrastructure, roadways and operational capacity on this transit project. The route was tested successfully in October 2017 when Indian shipments of wheat arrived at Chabahar from Kandla (Gujarat) and made their way into Afghanistan. There is much left to be done, including the building of a new railway route, but Trump’s sector-specific sanctions pose new complications.

Making Do and Muddling Through

Three years on, Chabahar’s progress does not match India’s original expectations and Trump’s exemption has proven to be inadequate.

This project was touted to be India’s first foreign port development endeavour. For many assessing New Delhi’s record on infrastructure development abroad, the Chabahar project is no longer a useful indicator. It continues to rely heavily on stopgap measures with neither Indian nor foreign companies coming on board. It was a venture that New Delhi could have fought harder to preserve. But the reality is that it chose not to—a decision that merits an entirely separate discussion on the nuances of the India-US partnership and Iran’s reduced place in it.

All signs today point to the stakeholders behind the Chabahar project muddling through with what exists on the ground in Iran. As one Indian official involved with the project since its origins lamented, “This was not what we hoped to achieve. Chabahar is only about photo-ops now, not substance.”

Photo; Logiscm.ir

It’s Time to Admit That We Don’t Understand Iran’s Economy

◢ Give US and European officials a simple quiz about the Iranian economy and they will fail to answer fundamental questions. A poor understanding of Iran’s economy is the single most significant gap in our perception of Iran and the nature of the conflict in which it is currently mired.

This article was originally published by the Atlantic Council’s IranSource.

Give US and European officials a simple quiz about the Iranian economy and they will fail to answer fundamental questions. What is the composition of the Iranian economy? Who sets economic policy and who influences policymakers? How do monetary and fiscal policies explain Iran’s economic resilience? How does Iran use its foreign exchange reserves? Is Iran’s trade with China growing at the expense of its trade with Europe? What does the Iranian public think about the state of the economy?

The United States is pursuing an “economic war” on the basis of a very crude understanding of Iran’s economy. Should the goal of its sanctions policy be havoc, such an understanding will suffice. But if the US is serious about using sanctions as a tool to coerce Iran to change its behavior, or by extension, if the US decides to one day use economic incentives to induce Iran to change its behavior, a nuanced understanding of Iran’s economy will have a direct bearing on the probability of success. A similar determination must be made about Europe’s belated effort to defend its economic ties with Iran in the face of US secondary sanctions—a poor understanding of Iran’s economy has comprised their defense.

US President Donald Trump’s economic war on Iran has had at least one positive impact. It has helped policymakers in the United States, Europe, and even Iran to realize the fundamental role that the economy plays in shaping how the foreign policies and national security strategies of Iran and global actors intersect. These actors are now scrambling to develop a more sophisticated understanding of Iran’s economy and a better package of measures to ease sanctions pressure. As part of this work, policymakers are calling upon the expertise of those individuals in Iran, Europe, and even the United States who possess insights about Iran’s economy. But if a deeper understanding of Iran’s economy is to truly underpin policymaking, institutional efforts will be required that improve how knowledge about Iran’s economy is produced and disseminated in three areas: business journalism, academic research, and corporate communications.

The world’s leading media outlets extensively report on Iran and there remains a limited but experienced corps of foreign correspondents based in Tehran. But the overwhelming editorial focus of foreign reporting from Iran is the politics, rather than economics of the country. This bias extends even to Bloomberg and the Financial Times, the powerhouses of global business journalism. While it is common to see reports on issues such as currency devaluation or rising inflation, particularly with regards to the impacts of sanctions on Iran, these reports tend to present a vox populi view of economic issues. There remains remarkably little reporting about economic policy in Iran or developments in either financial markets or industrial sectors. Similarly, English-language reporting on these issues from Iranian publications lacks global insights.

Of course, the lack of journalistic focus on Iran’s economy is itself a product of the country’s economic isolation. One of the main commercial drivers of financial reporting is demand for information from international investors—who have no real footprint in Iran. But if the intention of the current editorial focus on Iran is to inform global readers about phenomenon driving Iran’s political decisions and security strategy, it is significant oversight not to examine economic precursors in more detail. More effective reporting on Iran from a “world affairs” perspective requires grappling with the complex narratives of the Iranian economy.

In the area of academic research, there is a small contingent of professional economists in the United States and Europe who work on Iran. These individuals are overwhelmingly of Iranian heritage, and tend to look at Iran’s economy as just one part of their research focus, due to a lack of institutional and financial support available for Iran-specific research that is not focused on political or security issues.

Better academic research on Iran’s economy requires stronger institutional support from universities, think tanks, and research centers. Greater funding must be made available so that economists with an interest in Iran can gainfully pursue an Iran-focused research agenda. Cross-disciplinary outreach is necessary to help demonstrate the salience of economic insights to the political and sociological study of Iran, as well as more topical research areas such as the growing body of academic work on sanctions. Finally, the research findings of economists working on Iran should be much more proactively translated into insights for non-specialist audiences through the publishing of research notes, providing commentary to journalists, participation in public and private meetings for non-academic audiences, and the use of social media to reach interested audiences.

Of course, pressure from the Iranian government makes journalism and academic research in and about Iran difficult, and this remains true for work on Iran’s economy. At a time of “economic war,” the Iranian government considers reporting and research on Iran’s economy to be especially sensitive. But the simple fact that so much of the current body of research and reporting on Iran’s economy is focused on the impact of sanctions or published in the context of US national security concerns feeds Iranian suspicions. Establishing more diverse and collaborative research programs and initiatives can help “de-securitize” the study and understanding of Iran’s economy.

Finally, corporate communications remains under-developed in Iran. On one side, Iranian companies have yet to adopt best practices when it comes to corporate communications and investor relations. Many large and important enterprises have little more than a website and an occasional interview by a senior executive to shed light on their role in their given sector and developments in the sector at large.

On the other side, the foreign companies active in Iran, which better understand the importance of corporate communications, have been deterred from sharing information about their operations in Iran due to the reputational risks associated with sanctions campaigns. While many companies have maintained entirely legitimate and remarkably successful business operations in Iran in the sanctions period, most of these operations are essentially invisible for those outside of the country. In the absence of such information, US officials have had a free hand to characterize Iran’s economy as unusually opaque and corrupt, when it is probably only as opaque and corrupt as other developing economies—a reality understood by the foreign companies that stubbornly operate in the country.

These dynamics had shifted somewhat during the period immediately following the implementation of the nuclear deal. Several of the European large corporations active in Iran began to use corporate communications to highlight their market activities, in part to demonstrate to Iranian stakeholders a kind of pride about their market presence or market entry. But with the re-imposition of US sanctions, companies are once again skittish. As a result of these shortcomings in corporate communications, an understanding of the most important commercial enterprises in Iran, the nature of their ownership, their product offerings, and the general status of key industries and sectors is really only readily available to those individuals or organizations with a presence in Iran or who enjoy direct access to business networks. Company-level information about Iran’s economy remains difficult to obtain for both journalists and economists.

As Iran and the US find themselves trying to avoid stumbling into a military conflict, it may seem ridiculous to suggest that developing a more sophisticated understanding of the Iranian economy is essential to finding a pathway to diplomacy. But this moment of crisis emerged from the failure of sanctions relief following implementation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the hardship of the economic war now being waged by Trump, and the inability of the remaining parties of the nuclear deal to meet their basic economic commitments to Iran. Until policymakers are empowered with the insights generated by more business reporting, more academic research, and more transparent corporate communications, they will find their foreign policy and national security strategies inadequate to the task of securing peace. A poor understanding of Iran’s economy is the single most significant gap in our perception of Iran and the nature of the conflict in which it is currently mired

Photo: Nassredean Nasseri

Iran Delays Currency Reform Demanded by Private Sector

◢ Despite sharp criticism from the private sector, the Rouhani administration has delayed a key reform to Iran’s currency policy, frustrating the country’s beleaguered business leaders. In late June, government spokesman Ali Rabiei stated definitively that the administration has no plans to eliminate the subsidized foreign exchange rate made available to importers of essential goods.

Despite sharp criticism from the private sector, the Rouhani administration has delayed a key reform to Iran’s currency policy, frustrating the country’s beleaguered business leaders.

In late June, government spokesman Ali Rabiei stated definitively that the administration has no plans to eliminate the subsidized foreign exchange rate made available to importers of essential goods.

Iran’s current currency policy was April 2018 in the aftermath of a devaluation crisis that had formed in anticipation of the re-imposition of U.S. secondary sanctions as Donald Trump moved closer to his decision to withdraw from the JCPOA nuclear deal in May 2018. Subsequent rounds of sanctions and particularly restrictons on Iran’s oil exports have added further pressure to Iran’s currency markets.

Iranian policymakers responded to these pressures and the fast-rising cost of imported goods with a policy that plays into Iran’s multiple exchange rates and entails allocating foreign currencies to importers of essential goods at the “official” rate of 42,000 IRR/USD—a far lower rate than the current “open market” rate of around 120,000 IRR/USD.

The government operates a third rate, the NIMA rate, which is named for the online currency system that was established by the Central Bank of Iran (CBI) also in April 2018. The system is made available to exchange houses and banks that buy foreign currency and is where exporters are obligated to repatriate their export yields. In recent months, the NIMA rate has inched closer to the open market rate and now stands at around 110,000 IRR/USD.

For the private sector, the convergence of the NIMA and open market suggests the time is right to simplify the currency market. In late July, the Iran Chamber of Commerce, Industries, Mines and Agriculture (ICCIMA), the main representative body of the private sector, released a statement calling for the elimination of the subsidized rate and a long-term move toward rate unification.

The subsidized rate, the ICCIMA argues, contributes to already rampant inflation, enables rent-seeking activities and corruption, reduces general trust in government economic policy, and makes it harder for local manufacturers to compete with imports. Moreover, in the assessment of chamber members, the current policy of subsidization failed to prevent price increases for imported essential goods, which have outpaced inflation.

The ICCIMA has called on the Rouhani administration to eliminate the subsidized rate and move toward rate unification in the long-term by decreasing the gap between NIMA and open market rates in addition to levying capital gains tax on foreign currency trades. It has also said the government should redirect resources away from importers and instead subsidize the consumption of low-income households through cash subsidies, while also providing financing to local manufacturers to help reduce reliance on imports. Finally, the ICCIMA statement calls for the government to ease economic pressure on the private sector by repaying its outstanding liabilities to suppliers and contractors.

“Since the open market and NIMA rates have gotten so much closer, this is absolutely the right time to eliminate the subsidized rate,” ICCIMA board member Ferial Mostofi told Bourse & Bazaar.

“Let us accept that the official rate does not reflect the true value of our currency and try to focus on repatriating non-oil exports using the real rates so that we can have a chance at competing in international markets,” the prominent woman business leader added.

In early March, just before the start of the current Iranian year, the administration showed signs that it mulling whether to end the subsidization policy. CBI Governor Abdolnasser Hemmati admitted in a frank statement that subsidization had failed. “In effect, allocating subsidized currency to essential goods has failed to prevent their price hikes in the medium term due to the nature of market in the economy and the weakness of the distribution and supervision systems,” he said.

But in a June 23 televised interview, Hemmati did claim some success for the policy, noting that the price of essential goods rose by 40% on average during the previous Iranian year, whereas imported goods that did not receive the subsidized rate surged by 98%.

Furthermore, he argued that scraping the current three-tier currency policy during the current Iranian year was simply not worth the hassle. However, he did suggest that the government was trying to reduce the burden of the subsidized rate.

According to Hemmati, from the $14 billion that was approved by the parliament to be allocated to subsidize foreign exchange used to import essential goods in the current Iranian year, more than $3 billion was effectively eliminated when the government decided on April 28 to reassign four items previously listed as essential goods. Those items included meat products—which had experienced extreme price increase despite qualifying for subsidized foreign exchange– tea, butter, and beans.

From the remaining figure of less than $11 billion, Hemmati said, $5 billion was allocated by the time of his interview. Subtract an additional $3 billion that the central bank has said is required to ease imports of medicine and eliminating the remaining subsidy of less than $3 billion is deemed by Hemmati to be “not worth a new country-wide inflationary shock.”

Many private sector business leaders disagree. “There is no doubt that eliminating the subsidized currency policy will entail a price shock, but that shock will be short-term and very much worth it when compared to the long-term detrimental effects of the current policy,” ICCIMA’s Mostofi said.

In her view, if the main goal of the policy is to help middle to low-income families, policies should be adopted that do not spur corruption and waste away the country’s precious foreign currency reserves while the country is contending with a “maximum pressure” sanctions campaign.

Photo: IRNA

Abu Dhabi Can’t Afford To Keep Iran Out Of Dubai

◢ During the last financial crisis, capital flight from Iran offered a hidden bailout for Dubai as global investors pulled back. With a new crisis on the horizon, Iranian business leaders are wondering—how long can Abu Dhabi afford to freeze them out?

This article was originally published in LobeLog.

As the world teeters on the edge of another financial crisis, few places are being gripped by anxiety like Dubai. Every week a new headline portends the coming crisis in the city of skyscrapers. Dubai villa prices are at their lowest level in a decade, down 24 percent in just one year. A slump in tourism has seen Dubai hotels hit their lowest occupancy rate since the 2008 financial crisis, even as the country gears up to host the Expo 2020 next year. As Bloomberg’s Zainab Fattah reported in November of last year, Dubai has begun to “lose its shine,” its role as a center for global commerce “undermined by a global tariff war—and in particular by the U.S. drive to shut down commerce with nearby Iran.”

Dubai, an entrepôt where the workers are migrants and where property is king, is especially vulnerable to global recessions. In the immediate aftermath of the global financial crisis in 2009, Dubai’s real estate market collapsed, threatening insolvency for several banks and major development companies, some of them state-linked. Abu Dhabi, which controls the UAE’s vast oil wealth, threw Dubai a lifeline with an initial $10 billion bailout, later expanded to $20 billion.

But there was a second, hidden “bailout” that helped keep Dubai afloat. When the Bush administration enacted the Iran Sanctions Act in 2006, deepening Iran’s economic turmoil under President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, there was a significant increase in the already significant volume of capital flight from Iran, most of which landed in Dubai. One 2009 estimate places the total value of Iranian investments in Dubai at $300 billion.

While global investors pulled their capital out of Dubai in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, the Iranian business community mostly stayed put, maintaining their deposits in Dubai’s teetering banks. Iranians continued to invest in Dubai’s ailing property market and used Dubai’s ports to conduct re-exports as sanctions restricted Iran’s direct access to global markets. For Iran’s captains of industry and finance, Dubai was not some far flung emerging market, but a vital channel to the global economy in the face of tightening sanctions. As Iranian economist Saeed Laylaz smartly observed in 2009, “Dubai is the most important city on earth to the Islamic Republic of Iran, with the exception of Tehran.”

The financial crisis and U.S. sanctions had served to deepen the mutual dependence between Dubai and Iran—an outcome that ran counter to the goals of policymakers in both Abu Dhabi and Washington.

The Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and the defacto ruler of the UAE, Sheikh Mohammad bin Zayed (MBZ), has long seen Iran as a rival. MBZ is hostile to Iranian influence over Dubai, where many of the leading trading families can trace their roots to Iran, a legacy of centuries of trade in the Persian Gulf. MBZ’s dream of an assertive UAE would have been undercut had Dubai continued to develop into the Hong Kong to Iran’s China.

The Obama administration’s effort to build a multilateral sanctions campaign offered MBZ the opportunity to curtail Iran’s presence in Dubai’s economy. As they sought to isolate Iran economically, U.S. officials traveled to Dubai to meet with banks and companies to discourage them from engaging in commercial activities with Iran. Rather than resisting U.S. interference in the UAE’s economic sovereignty, Abu Dhabi amplified the American message– the bailout had put Abu Dhabi in a position to dictate policy to Dubai. The new policy called for Dubai to close its doors to Iranian money.

In subsequent years, the presence of Iranians in Dubai’s economy has diminished significantly. Trade persists, but banks refuse Iran-origin funds, close the accounts of Iranian companies, and deny services to individuals who maintain Iranian citizenship. More recently, as the Trump administration cultivated ties with MBZ, the UAE began to reject more Iranian applications for residency and business visas were routinely denied. Nearly 50,000 Iranian residents have left the UAE in the last three years.

But there are new signs that Dubai may be seeking to repair its trade relationship with Iran. In a recent interview, Abdul Qader Faghihi, president of the Iranian Business Council in Dubai, declared that a “space for trade between Iran and the UAE has been reopened.” Though any opening remains in its initial stages, Faghihi referred to negotiations with “the rulers of Dubai” in which Dubai authorities “accepted that Iranians who have the capital and intend to conduct legitimate trade with the UAE will be granted business visas and that banks will open accounts for these Iranians on instruction from Dubai authorities.”

This small opening may be related to efforts to reduce tensions around the Strait of Hormuz as Abu Dhabi reconsiders its regional entanglements and the risk of conflict in the region—it is unlikely that Dubai would be able to extend an olive branch to the Iranian business community without the consent of Abu Dhabi. But economic fears, and not security concerns, provide the clearest reason why a change in policy may be on the cards—Dubai will soon need another “bailout” from Iran. Farshid Farzanegan, head of the Iran-UAE Joint Chamber of Commerce, recently stated “The UAE’s behavior towards Iranian businessmen has changed… and moves are being taken to resume relations… As the UAE economy slumps, officials have decided to cooperate with Iran.”

Ten years on from the last financial crisis, Dubai is still repaying its debts to Abu Dhabi. As the UAE braces itself for the next global recession, Iran remains the only country capable of injecting significant capital into Dubai at a time when global investors will pullback. Iranian business leaders in Dubai are wondering—how long can Abu Dhabi afford to freeze them out?

Photo: Wikicommons

Trump’s NSC ‘Blocks’ Swiss Effort to Ease Iran Humanitarian Trade

◢ Last year, the Swiss government opened negotiations with the Trump administration to ensure that Switzerland’s significant sales of pharmaceutical products and medical devices—technically exempt from U.S. sanctions—could continue unimpeded. But the National Security Council has so far prevented the Swiss effort to ease trade in food and medicine in a remarkable subversion of longstanding U.S. protections for humanitarian trade with Iran.

In November of last year, as the Trump administration reimposed secondary sanctions on Iran and embarked on its “maximum pressure” policy, the Swiss government opened discussions with the Treasury and State Departments to ensure that Switzerland’s significant sales of pharmaceutical products and medical devices—technically exempt from U.S. sanctions—could continue unimpeded.

But the hardline sanctions policy being pushed by the National Security Council has so far prevented a Swiss effort to ease trade in food and medicine in a remarkable subversion of longstanding U.S. protections for humanitarian trade with Iran.

According to Swiss customs data, in 2017 Switzerland exported CHF 236 million in pharmaceutical products to Iran. Last year, the total fell to just CHF 164 million, hampered by both the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal and volatility in Iran’s foreign exchange market. In the first half of this year, exports have totaled CHF 79 million.

European companies engaged in trade with Iran have become adept at finding payment solutions in the absence of normal correspondent banking. Some European and Swiss banks continue to process Iran-related transactions for sanctions-exempt trade, particularly for large clients with longstanding commercial relationships in Iran.

But when trade manages to flow despite the direct and indirect effects of sanctions, it is often with higher transaction costs for all parties, which are then passed onto the consumer. Additionally, many advanced therapies or specific medical devices are produced by smaller Swiss companies, which do not have the same capacity as major Swiss pharmaceutical firms to find alternative payment solutions to sustain their trade with Iran. Hidden in the trade data is the reality that specific medications are not being sold to Iran as reliably, contributing to the shortages that have compromised the treatment of many of the most vulnerable Iranians, particularly those with chronic illnesses.

In light of such challenges, which were first experienced under Obama-era sanctions, the Swiss government entered into discussions with the Trump administration, seeking additional clarity for Swiss banks engaged in humanitarian trade around “two key challenges.” As described by a Swiss official to Bourse & Bazaar, the Swiss government was seeking “some sort of ‘certainty’ for banks involved [in humanitarian trade with Iran] so that they will not be excluded from the US market.” Additionally, the Swiss government was hoping to provide their banks clarity on the permissibility of “the transfer of Iranian-origin funds into the Swiss accounts” when Iranian importers pay Swiss importers for humanitarian goods.

Early discussions proceeded quickly, not least because the Swiss were seeking to reinstate a compliance model that had been used by the Treasury and State Departments before, during the period in which the Obama administration was tightening its secondary sanctions on Iran. In late January, several reports indicated that the payments channel had become operational—that was incorrect. Despite delays, Swiss officials believed they were in the “final stages” of launching the payment channel in February. They too were mistaken.

Six months on, the Swiss government and Swiss banks have yet to receive any meaningful clarity from the Trump administration on their proposed channel for humanitarian trade. As NBC’s Dan de Luce reported in March, administration officials were still debating “a proposal from Switzerland to set up a humanitarian payment channel that would encourage Swiss banks to handle sales of medicine, medical devices and other items to Iran without fear of violating U.S. sanctions.”

Importantly, what the Swiss are proposing is entirely consistent with existing U.S. sanctions laws and does not seek to undermine secondary sanctions powers. The Swiss approach does not entail the creation of a special purpose vehicle in the manner of INSTEX, the company established by the French, German, and U.K. government to support their sanctions-exempt trade with Iran. The INSTEX project was itself launched after the Trump administration rejected a request by the E3 governments for expanded waivers covering humanitarian trade.

European officials with knowledge of the Swiss negotiations tell Bourse & Bazaar that while officials at the State Department and Treasury Department had quickly understood the intention and importance of the Swiss request and moved to provide the requested assurances, the necessary administrative actions were later “blocked” by officials at the National Security Council, which has taken an unusually active role in sanctions policy in this administration.

The debate over the Swiss humanitarian trade mirrors similar disagreements among key administration officials about the reasonable limits of the Trump administration’s maximum pressure campaign. Led by John Bolton, the NSC has taken the same hard stance in debates around the revocation of the oil waivers permitting controlled exports of Iranian oil, around the sanctions designation of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), and around the partial revocation of waivers that permit civil nuclear projects central to the non-proliferation commitments of the JCPOA.

Earlier this week, the State Department published a video in which Special Envoy for Iran Brian Hook sought to dispel several “myths about sanctions that continue to be promoted by the Iranian regime,” including “myth” that sanctions target humanitarian trade. Back in December of last year, the State Department provided a supportive statement to the Financial Times in response to questions about the Swiss payment channel, declaring: “We understand the importance of this activity since it helps the Iranian people. It has never been, nor is it now, U.S. policy to target this trade.” Officials at the NSC apparently disagree.

Photo: Wikicommons

INSTEX Develops New Service in Bid to Fast-Track Iran Transactions

◢ The state-owned company at the center of European efforts to save the Iran nuclear deal is entering its next phase of development. In a push to process transactions more quickly, INSTEX is rolling out a new factoring service for European exporters. The company is also making new hires that will enable it to expand operations more quickly in the coming year.

The state-owned company at the center of European efforts to save the Iran nuclear deal is entering its next phase of development. In a push to process transactions more quickly, INSTEX is rolling out a new factoring service for European exporters. The company is also making new hires that will enable it to expand operations in the coming year.

Having reached the end of his six-month contract, Per Fischer is stepping down as the president of INSTEX, the state-owned company established by France, Germany, and the United Kingdom to support trade with Iran. Fischer’s replacement is former German ambassador to Iran Bernd Erbel. A career diplomat, Erbel has been posted in Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt, and served as ambassador to Iraq prior to his stint as ambassador to Iran.

The change in leadership comes as INSTEX finalizes several other management hires. By filling these roles, INSTEX will enter a new phase of operation as a standalone company based in Paris. Until now, both INSTEX’s outreach to European companies and its coordination with its Iranian counterpart, STFI, has been led by civil servants at the foreign and economy ministries of the company’s three founding shareholders.

Fischer, a former Commerzbank executive, had been selected as the company’s first president due to his banking background. But Erbel, who lacks commercial experience, will have a different mission as he assumes his leadership role. Erbel will leave key commercial responsibilities to the new managers, focusing instead on ensuring a constructive working relationship between INSTEX and STFI. In recent weeks, cooperation between the two entities has slowed. Iranian authorities have called for INSTEX to be funded by Iran’s oil revenues—a move that would leave INSTEX vulnerable to sanctions from the United States.

Erbel’s deep knowledge of Iran may help him navigate the tensions surrounding the INSTEX project in Tehran and reassure Iranian stakeholders of the seriousness of European efforts to develop the mechanism further.

The goal for INSTEX remains to ease Europe-Iran trade by developing a netting mechanism that eliminates the need for a cross-border financial transactions. In this model, INSTEX will coordinate payment instructions between companies engaged in bilateral trade between Europe and Iran, enabling European exporters to receive payment for sales to Iran from funds that are already within Europe. The counterpart entity, STFI, will then mirror those transactions, allowing Iranian exporters to get paid with funds already in Iran.

Delayed by political disagreements, INSTEX and STFI remain in the process of establishing the netting mechanism. But in a bid to fast-track transactions, INSTEX has opted to roll out a new service that does not require the direct participation of its Iranian counterpart. INSTEX is now in advanced negotiations to a provide factoring service to an initial cohort of European companies.

In factoring transactions, INSTEX will purchase the expired invoices of European exporters who have failed to receive payment for sanctions-exempt goods sold to Iran. The focus on expired invoices allows INSTEX to avoid lengthy French regulatory approvals for a full factoring service. Importantly, INSTEX will not require the goods in question to have been delivered to the Iranian buyer in order for the European exporter to factor its receivables. In this sense, the service approximates a kind of trade finance.

According to a draft contract between INSTEX and a European company seen by Bourse & Bazaar, the purchase price paid to the European exporter by INSTEX would amount to 95 percent of the “assigned receivable.” In other words, INSTEX will charge a 5 percent fee as part of its factoring service. This fee will vary based on the transaction.

Such costs are not negligible for European exporters, especially when considering that INSTEX will require each transaction to undergo third-party due diligence at the exporter’s expense. Yet they are commensurate with the transaction fees typically charged by banks in those cases in which the bank is willing to accept funds originating in Iran. Moreover, for European companies burdened with unpaid invoices, the certainty of payment from INSTEX, a state-owned European company, is inherently attractive.