Just $10 Billion Could Fundamentally Change Iran's Economy

◢ As Henkel's recent moves show, investments can be made most quickly and with the largest economic impact in Iran's private sector.

◢ By targeting 100 private sector companies, with a maximum average transaction value of USD 100 million, just USD 10 billion could fundamentally change Iran's economy.

As we approach the end of 2016, the most important deal concluded for post-sanctions Iran this year was not among the headline-grabbing agreements signed by Boeing, Airbus, Renault, Siemens, Shell, or Total. Rather, it was a much smaller deal that received absolutely no coverage in the international business media.

In May of this year, German FMCG manufacturer Henkel purchased the remaining shares in its local joint-venture, Henkel Pakvash, taking its ownership to 97.7%. The company was able to deploy EUR 62 million to make the acquisition by purchasing shares on Iran’s Fara Bourse. In August, Henkel subsequently purchased the detergent business of Behdad Chemical for approximately EUR 158 million.

Henkel’s two transactions should be considered the most important of 2016, not only because they were successfully completed (in contrast to many of the larger deals that remain at contract stage), but also because these transactions are reflective of the most important kind of capital deployment for Iran’s near-term economic growth.

Both supporters and opponents of the Iran Deal have been focused on the billion-dollar contracts being made between major multinationals and Iranian state-owned enterprises. The logic is simple. Iran is a large economy and the true economic value of the Iran deal will only be reached when the country receives billions of dollars of foreign direct investment.

Iranian officials have boasted of a USD 50 billion target for FDI in 2016, a massive leap from the USD 2 billion registered the previous year. Reports suggest that Iran will more likely achieve around USD 8 billion. It took the Russian economy eight years (from 1999 to 2007) to see FDI inflows rise from levels commensurate with the current levels in Iran to the USD 50 billion milestone. While the process may take less time in Iran, business leaders and policymakers need to focus on what can be achieved in the next year.

By necessity, larger deals operate on longer timeframes. It will take years for Airbus and Boeing to complete their deliveries, or for Shell and Total to start pumping oil, and for Renault and Daimler to ramp up production. In effect, the contracts signed today will only manifest their full economic value in the next five to ten years.

In the private sector, timeframes for investment are much shorter. As the Henkel deals show, investment in private sector firms can happen quite quickly, even just months after Implementation Day. These transactions are the potential spark for Iran’s economic engine and they represent the overlooked landscape of Iran’s economy. The bulk of untapped economic value lies in the private sector.

Privately-owned companies maintain dominant positions in consumer-facing sectors such as FMCG, food and beverage, pharmaceuticals, consumer technologies, and hospitality and tourism. These companies, some of which are family-owned and some of which are publicly-held, are led by a globalized class of managers, many of whom have studied and lived abroad. Therefore, these companies operate much closer to international best practices for key functions such as accounting, supply chain management, human resource management, and marketing and communications. While many of these firms are under financial duress due to the lasting effects of sanctions, they nonetheless possess strong market share and significant cash flow, making them ripe for turnarounds. Some are in superb financial shape.

Most importantly, these companies are identifiable, if not widely known. While the firms and their owners have remained out of the limelight of Bloomberg, Reuters, or the Wall Street Journal, the grapevine in Tehran has a way of determining which companies deserve to be counted among the top 100, and which are the true standouts. The much talked about “positive list” of clean and compliant companies already exists—one just has to be on the ground in Tehran long enough to catalogue it. This is a small group of companies, at most numbering around one hundred . The very largest of these companies generate around USD 1 billion in revenue. As such, most of these enterprises would require relatively little capital for a strategic or financial investor to take a meaningful, if not a majority, ownership position. This is particularly true if one considers that leveraged buyouts—with debt financing coming from Iran—could be part of the capital solution. Realistically, the value of the purchased stakes, whether majority or minority, would rarely exceed USD 200 million and would probably average between USD 20 to 50 million.

Such transactions are small enough that they would enable the investing company or fund to mitigate the banking sector challenges that are currently throttling Iran trade and investment. The smaller banks that have begun to work with Iran are equipped to handle transactions of this size without breaking their balance sheets. By the same token, it is far easier to convince a large bank to facilitate a smaller transaction on the back of significant investor-led due diligence. Strong evidence for this can be seen in the success of Pomegranate, a Swedish investment fund, in deploying approximately EUR 60 million into Iran's tech sector.

Looking for one hundred companies with a high average acquisition transaction value of USD 100 million dollars means that a total of just USD 10 billion is needed to trigger a fundamental change in Iran's economy across numerous levels, from company operation to macroeconomic conditions.

Foreign investment is a protracted process. It will make an impact on the acquisition target at numerous stages, as new strategic shareholders take positions across Iran’s private sector. In the vetting stage, private sector firms will need to prepare themselves for due diligence, taking further steps towards better accounting and corporate governance practices. These firms will also have to embrace internationalization, becoming more knowledgeable of the global commercial landscape, and improving their capacity to engage with foreign investors or partners. When executed, the investment itself will fund knowledge and technology transfers, with the new foreign owner proving their “value-add” by helping the Iranian company make improvements in management and operations.

While the above benefits take place at the microeconomic level, there is a strong body of economic research from Iran that outlines the macroeconomic impact of private sector investment. In 2005, economists Pirasteh Hossein and Farzad Karimi examined how investment priorities in Iran could be aligned to “priorities in production and employment” in order to reduce unemployment and better address “[Iran’s] process of development.” One key finding was that “from an investment point of view, "the service sector and FMCG manufacturing are the two areas that can be considered the “‘great winners’ in generating aggregate employment due to investment.” The authors further note that private firms dominate these sectors. Therefore, “more private sector activity is warranted, since this will spread employment opportunities all over the economy with a faster pace.”

While the paper and its data are over a decade old, the fundamental findings may be even more valid today. Given the date of publication, the authors did not account for the additional impact of post-sanctions investment. They could not have predicted the great strides the private sector has made over the last decade. Certainly, there is ample research that establishes the “positive correlation between growth of national incomes and private investment ratios.” Research also shows that foreign direct investment drives greater private domestic investment in what is called a “crowding in” effect.

Finally, in today's world, trade flows are fickle. An anti-globalist turn in politics makes trade a weaker link for constructive international relations. For Iran to achieve true integration into the global economy, shareholder equity will be the tie that binds. By bringing more foreign shareholders into it's economy, Iran will rise in importance in the economic agendas of its European partners.

A direct investment of USD 10 billion is smaller than the total value of the Boeing/Iran Air deal. Growth capital, triggering value-creation, is what is needed at this crucial moment. Deploying a mere USD 10 billion of such resources into Iran's private sector in the next few years will create more economic value than pouring even larger amounts of capital into mature, state-owned enterprises. Investors and policymakers should take note.

Photo Credit: Henkel

How Rex Tillerson's Oil Industry Politics Could Boost the Iran Deal

◢ ExxonMobil CEO Rex Tillerson will reportedly be named Trump's new Secretary of State, ending speculation about the critical role for US policy on Iran.

◢ Tillerson's public comments on sanctions and Iran give some indication that he will take a pragmatic view of the Iran Deal.

It has been widely reported that Rex Tillerson is to be named the next Secretary of State, ending speculation about perhaps the consequential cabinet post for the prospects of Iran policy in the Trump administration.

Tillerson’s appointment has shocked many. As the Chairman and CEO of ExxonMobil, he has no formal diplomatic or political experience. Tillerson is also a friend of Vladimir Putin, having built his name as a regional executive for ExxonMobil in the Caspian region in the late 1990s.

Some commentators have suggested that Tillerson’s appointment as Secretary of State will bring the back-room politics of the global oil industry into the heart of American foreign policy. Given the problematic role that oil companies have played in international relations, this may give cause for concern. However, for the prospects of Iran Deal implementation in the Trump administration, Tillerson’s appointment could represent the entry of a pragmatic figure who can look beyond the ideological fixations of people like John Bolton, his reported deputy. Tillerson’s public comments offer clues to his outlook.

Tillerson Does Not Believe in Sanctions

In a May 2014 ExxonMobil shareholder meeting, Tillerson stated, “We do not support sanctions, generally, because we don’t find them to be effective unless they are very well implemented comprehensively and that’s a very hard thing to do.” For a global company like ExxonMobil, which works in politically tumultuous markets, sanctions are an inherent risk to business. For example, Exxon has a pending project with Rosneft worth a reported USD 300 billion that is unable to proceed due to US sanctions.

Given that there has been a renewed call in Washington for new, non-nuclear sanctions to be levied on Iran, Tillerson’s general disbelief in the efficacy of sanctions is important. This is particularly the case as Europe, China, and Russia have each signaled that they will not cooperate with any US attempt to renegotiate the Iran Deal—making comprehensive implementation of any new sanctions impossible.

Tillerson Wanted To Get Exxon Into Iran

In an interview with CNBC from March of this year, Tillerson made it clear that he saw Iran as an attractive market for ExxonMobil, despite US sanctions. He stated:

U.S. companies like ours are still unable to conduct business in Iran. A lot of our European competitors are in, working actively. I don't know that-- that we're necessarily at a disadvantage. The history of Iranian-- in foreign investment in the past, their terms were always quite challenging, quite difficult. We--never had large investments in Iran for that reason. And I don't know that the Iranians are gonna be any different today. We'll have to wait and see and there hasn't been any contracts put out. But I also learned a long time ago that sometimes being the first in is not necessarily best. We'll wait and see if things open up for U.S. companies. We would certainly take a look because it's a huge resource-owning country.

Since he made these comments, Iran has unveiled its new IPC oil contracts and oil majors Total, Shell and DNO have all signed heads of agreement outlining the terms of new investments in oil and gas production in Iran. Tillerson will see his former peers at the oil majors making huge strides in the market and will likely see this as a perfectly natural development for an economy coming out of an onerous sanctions regime.

Tillerson Sees Multinationals as Private Empires

As described in Steve Coll’s increasingly relevant history of the firm, Private Empire, ExxonMobil developed into the world’s largest company by pursuing interests very different from those of the US foreign policy. Tillerson’s predecessor, Lee “Iron Ass” Raymond once declared, “I am not a U.S. company and I don’t make decisions based on what’s good for the U.S.” For all intents and purposes, Tillerman, who rose through the ranks at Exxon, absorbed this outlook.

Raymond’s statement is particularly noteworthy given the intense focus of the current U.S. sanctions regime on defining U.S. and non-U.S. entities or persons and delineating the scope of Iran business that is accordingly permissible. The dilemma facing many of the world’s largest multinationals and financial institutions is that while they do not necessarily see themselves as “U.S. companies,” they are nonetheless treated as such by U.S. regulators. As a result, business interests in Iran become much more difficult to operate.

Tillerson may be sympathetic to rising calls from major European multinationals across industries for the U.S. to be more proactive in the implementation of the Iran Deal, and in particular, to reduce the extraterritorial nature of its regulatory oversight by changing the extent to which global companies can be reduced to US legal entities.

What About Miles’ Law?

There is an old adage of political science called Miles’ Law that describes how perspectives on policy change depending on one's position within the state bureaucracy: “Where you stand depends on where you sit.”

It may be that in assuming the role of Secretary of State, Tillerson will adopt a more inherently political and therefore oppositional attitude towards Iran. Certainly figures like John Bolton will seek to push Iran policy in a much more hawkish direction.

But Tillerson will ostensibly have the greatest authority in the ongoing treatment of the Iran Deal, inheriting the hands-on role defined by Secretary Kerry. As an oil industry CEO named "Rex," he likely has the advantage over Bolton in getting subordinates to bend to his will. Trump is also more likely to see Tillerson as a peer.

The present implementation of the deal benefits from the expertise and management of career civil servants like Ambassador Stephen Mull and Chris Backemeyer, who could be encouraged to stay on the Iran file if Tillerson adopts a pragmatic approach. Tillerson could run his State Department as a private empire, allowing the overall tenor of the incoming administration’s foreign policy to be defined by Trump and his more vocal acolytes, but ensuring that the execution of State’s diplomatic aims retains a more businesslike, if not outrightly commercial, logic. This would not be too dissimilar from the operation of the Iranian MFA within the overall context of the political posturing of the Islamic Republic.

Those who support the deal can find some comfort in the idea that a career of training in the realist politics of the oil industry may make Tillerson a more pragmatic voice in Trump’s cabinet, one which may see the Iran Deal as an appropriate measure that addresses key security concerns, but also provides the world’s private empires desired access to a promising market.

Photo Credit: Fortune

Smarter Iran Policy Could Give Trump Leverage to Protect American Jobs

◢ Donald Trump recently underscored his intention to protect American jobs by making an extraordinary intervention at a Carrier factory in Indiana.

◢ A look at Carrier and Indiana's other top employers illustrates how across the United States, major businesses have traded with Iran. Trump should use Iran policy as leverage to either boost US exports, or incentivize multinationals to keep American jobs.

Last week, President-Elect Donald Trump and Vice-President Elect Mike Pence traveled to Indianapolis, Indiana to save American jobs. In a speech at a manufacturing facility of Carrier Corporation, a subsidiary of United Technologies Corporation (UTC), Trump announced that the company would preserve approximately 1000 jobs it had planned to outsource to Mexico and would make a new investment to preserve the competitiveness of its Indiana manufacturing facility. In exchange for its compliance, UTC would receive significant tax incentives.

The Wall Street Journal editorial board called the Carrier intervention a “shakedown,” and it was shocking to many that President-Elect Trump would go so far as to interfere in the decision-making of a private enterprise in order to preserve a small number of jobs.

By a similar token, members of the business and policy communities were dismayed to learn that the Trump administration may seek to interfere in the Iran Deal more deliberately and quickly than previously thought. While Trump was making his announcement at Carrier in Indianapolis, the U.S. Senate voted unanimously to renew the Iran Sanctions Act. The following day, it emerged in a report in the Financial Times that the Tump transition team is exploring new non-nuclear sanctions.

But what if Trump is missing out on the chance to win big on both job creation and Iran policy by connecting the two efforts? The potential nexus of Iran policy and jobs policy is clear. Either Iran can be a direct destination for American-made goods, unleashing a new and highly valuable export market, or, Trump can use his powers to permit non-U.S. companies to more freely trade with Iran, offering a growth opportunity that may enable executives to forego cost-saving layoffs in the US.

Indiana, where Trump and Pence stood up for American jobs, illustrates the salience of Iran to American business interests quite well. Nearly every major multinational corporation with operations in Indiana, counting among them many of the state’s largest employers, have had or currently maintain business dealings with Iran.

When Trump met with Gregory J. Hays, CEO of UTC, at Trump Tower to negotiate the preservation of the jobs at Carrier in Indianapolis, he probably did not realize that instead of offering a tax incentive, he could easily use his future executive powers to enable Carrier and UTC to resume doing business in Iran, a market that was once highly lucrative.

In 1972, Carrier invested USD $2.4 million (equivalent to nearly USD $15 million today) in order to acquire 50% of Carrier Thermo Frig (CTF), an Iranian manufacturing joint-venture. CTF operated until the Islamic Revolution, growing steadily and paying its shareholders a dividend of just over USD $1 million in 1978 (equivalent to nearly USD $4 million today). While the numbers may seem small, it is worth considering the unrealized growth potential. In neighboring Turkey, Carrier Corporation currently owns 50% of Alarko Carrier, a manufacturing venture similar to that of the former CTF. In 2016, Alarko Carrier generated USD $131 million in revenue.

Today one can still find Carrier air condition units in Iran. Some are old models from the CTF days, others are newer models imported via the grey market. These are serviced by Sarma Afarin Industrial Co. a publicly traded company, which emerged from CTF when Carrier pulled out from Iran in 1979. Sarma Afarin still manufactures climate control units based on Carrier designs.

A couple of days after announcing the Carrier outcome, Trump turned his attention to Rexnord, a diversified industrial company.

Just like Carrier, Rexnord had direct business dealings in Iran prior to the Islamic Revolution, and then continued supplying Iran through non-U.S. subsidiaries. The company only began to completely wind down its trade with Iran through in 2009, according to regulatory filings. Iranian companies continue to source and service Rexnord systems through the secondary market.

The incoming administration should realize that the Carrier and Rexnord cases are not exceptions when it comes to Indiana or America's Iran business ties. For example, Indiana is a leader in the American pharmaceutical industry. One of the state’s largest employers is Eli Lilly, which has its global headquarters in Indianapolis. According to regulatory disclosures, the company currently supplies “medicines for patient use in Iran.” The company exports to Iran and conducts related activities “in accordance with our corporate policies and licenses issued by the U.S. Department of the Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control.” The encouragement of the Trump administration would certainly help Eli Lilly penetrate the Iranian market, which is becoming a goldmine for European pharmaceutical companies. American firms are being left out.

Indianapolis is also home to the sprawling North America headquarters of Switzerland's Roche Diagnostics, which researches, develops, and manufactures laboratory equipment for the analysis of medical samples. Under licenses and exemptions for medical equipment, Roche exports diagnostic equipment to Iran through its local agent, Akbarieh. While Roche products manufactured in Indiana are not imported directly to Iran, the research and development performed in Indianapolis informs the rollout of products in the country. Other sections of Roche’s business are operated locally by Roche Pars, a wholly-owned Iranian subsidiary established in August, 2013. Roche Pars is currently the fastest growing pharmaceutical company in Iran, registering 50% annual sales growth as it approaches 5% market share.

Indiana boasts a proud history of transportation manufacturing. The state is home to the world’s sole manufacturing plant for Toyota’s midsize Highlander SUV. While the Highlander is not currently sold in Iran, Toyota’s RAV4 and Corolla models are strong sellers with nearly 4,000 models sold since March of this year. The Highlander would likely do very well, as two of its direct competitors are among the most popular imported models in the country. The Hyundai Santa Fe is Iran’s top selling imported car, followed closely by the Kia Sorento. However, if the Trump-Pence team did decide to unleash Indiana’s mighty Highlander on the Iranian market, they would have to extend an olive branch first, as Iranian legislators have blocked the import of US-manufactured automobiles in retaliation for the US renewal of the Iran Sanctions Act.

According to a 2012 filing to the Securities and Exchange Commission, Cummins, a world-leader in diesel engines and generators, continued exports to Iran via its European subsidiary until 2010, when sales totaled approximately USD $1.3 million. Just two years earlier, sales were USD $5.7 million. As sanctions have tightened, third party importers have stepped in to divert generators produced in Cummins’ factories in places like Chongqing, China and Pune, India to Iran. Neither Cummins, nor the workers at its Seymour, Indiana factory, now benefit from what was once a promising market.

Rolls Royce’s Indianapolis facility produces “more Rolls-Royce products... than anywhere else in the world” according to its website. While this facility primarily produces small to medium civil aircraft engines and marine and helicopter engines that are not currently exported to Iran, the company has expressed that it welcomes Iran Air’s pending acquisition of Airbus aircraft that will be powered by the larger Rolls-Royce Trent-series engines. In addition, the company is reportedly in talks with Iranian energy authorities to determine whether Rolls-Royce diesel and gas generation systems can be acquired as part of upgrades to Iran’s power infrastructure.

There are almost certainly other companies in Indiana that would benefit from an enabling of trade ties with Iran. In 2014, NIAC, an advocacy group, published a report that examined the total value of US export revenue to Iran forgone between 1995 and 2012 due to the imposition of sanctions. The researchers found the total value of lost exports to be as high as USD $175 billion. In addition, the lost exports translate to an average of 66,000 jobs lost each year.

Even in the American heartland of Indiana, the economy depends on the success of major multinational corporations, some headquartered locally, others operating foreign outposts. For nearly all of these companies, Iran is a market of significant interest. If the Trump administration wants to be known for its business acumen, it should think more creatively as to how best to incentivize global corporations to preserve American jobs. Rather than using public pressure and tax incentives to compel global companies, Trump should offer opportunities that encourage growth and ambition.

Given the renewal of the Iran Sanctions Act, it remains the prerogative of the executive branch to green-light Iran trade through the provision of OFAC licenses. Donald Trump has clearly realized that his new role as President-Elect gives him immense influence over some of the world’s largest corporations. He should use that leverage to give big business what it wants—new markets in which to compete. For the workers at Carrier, Rexnord, Eli Lilly, Roche, Toyota, Cummins, and Rolls Royce, anything that reduces the pressure on their executives to slash costs could make all the difference. Currently, European products dominate Iran's marketplace. Products made in Indiana—and indeed in all fifty states—could find a hugely receptive market in Iran. The Trump administration would be wise to take heed.

Photo Credit: Wikicommons

For Iran's Supermarkets, Bigger May Not Be Better

◢ Hypermarkets now account for 2% of the total value of the grocery market in Iran, and 15% of the market in Tehran.

◢ But as hypermarket growth begins to stall in Europe, retailers in Iran should take heed. Similar consumer trends are likely to manifest in Iran in the coming years. Big stores won't be enough to win sales.

Supermarkets have long been associated with modernity in Iran. The Shah, who was contemptuous of the “worm-ridden shops” of the traditional Iranian bazaar, writes in his memoirs “I could not stop building supermarkets. I wanted a modern country.” The early leaders of the Islamic Republic also wanted a modern country, and continued to build supermarkets. Most of Iran’s chain retailers are state-owned or state-affiliated enterprises. Etka Chain Stores Company, established in 1955, is controlled by the economic holding company of Iran’s armed forces. The Tehran municipality launched the Shahrvand chain in 1993. Bank Melli, Bank Tejarat, and Bank Saderat jointly launched the Refah chain the following year. Whereas the Shah was apparently building supermarkets for vainglorious reasons, the economic planners of the Islamic Republic found chain stores appealing for the ability to more directly manage supply chains and pricing.

The introduction of greater efficiency continues to motivate the modernization of Iran’s retail sector, and thereby modernize the economy at large. As part of the push for privatization that began in earnest fifteen years ago, however, the emphasis for retail sector development was moved away from state ownership. Under the Sixth Five-Year Development Plan, Iran aims to increase the share of chain stores in the retail market by 10%, but the onus of that growth is clearly on the private sector. There is plenty of potential.

Market research firm Vistar Business Monitor estimates the total value of Iran’s retail sector at USD $70 billion, of which only 8.5% can be attributed to chain stores, including hypermarkets. Traditional retailers such as neighborhood shops and bazaar vendors account for the remaining 91.5%. In Tehran, the total value of the retail market is estimated at USD 12 billion, of which 15% is attributable to chain stores.

The largest retail chain by number of stores is Etka, with nearly 500 outlets. By way of comparison, Europe’s leading food retailer, Carrefour, boasts over 6000 hypermarkets, supermarkets, and convenience stores in France alone. Given that Iran has a larger population than France, it would be easy to explain the lack of chain stores as related to the country’s lower consumer purchasing power. The average grocery-spend per household in Iran is around IRR 80 million, or roughly USD 2500. Accounting for 3-4 individuals per household, this equates to a per capita spend of roughly USD 650-800. This is on par with spending in Russia and Eastern Europe and far below the USD 3400 spent per capita in France.

Not surprisingly, purchasing power in Tehran is about three times higher than the national average. Tehran boasts a per capita grocery spend of around USD 2400, which brings this segment of the market closer to the average expenditure seen in countries like Belgium, Netherlands, and Germany. International retail brands have taken note of this spending power. The push for new retail formats coincides with Iran’s post-sanctions growth and development and the entry of international players into the Iranian market. Most notably, French retail giant Carrefour entered the Iranian market in a joint venture with Dubai-based conglomerate Majid Al Futtaim. The two companies launched “Hyperstar,” a clone of Carrefour’s highly successful hypermarket format. The first Hyperstar opened in 2009 in Tehran, and the brand has since expanded its footprint in Tehran and has added branches in Esfahan and Shiraz.

But other hypermarket brands such as France’s Auchan and Germany’s Rewe Group have yet to seriously look at Iran. Part of this reticence may be due to the fact that Iran is a difficult market to navigate from a supply chain and operations perspective, but it also reflects the fact that many of the leading grocery retailers are facing new challenges at home. While hypermarket expansion was the key driver of sector growth for the last twenty years, these massive stores, typically over 5,000 square meters in size, have begun to falter in their profitability. Across Europe, hypermarkets grew by 4.3% annually from 2004-2012. This figure is projected to fall to 2% from 2013-2018, falling below expected growth among neighborhood shops (2.6%), discounters (4.6%), and convenience stores (5.3%). Some of the drivers of the slowdown—market saturation, lack of investment, and real estate development costs—will not pose a barrier to hypermarket expansion in Iran anytime soon. However, three drivers reflect important considerations for the next wave of retail development in Iran.

First, consumers around the world are tiring of “one-stop shopping” in which a single weekly trip is made to purchase groceries and necessities in large quantities. Part of the reason for this is reduced need. Household sizes across the European Union have been dropping consistently over the last few decades and have now settled at 2.3 individuals. The most common household is a single person household, accounting for one-third of all households in the EU. While Iran’s current average household size is closer to the levels seen in Europe 50 years ago, the size is inflated by the fact that long-term economic instability has led to children continuing to live with their parents well into adulthood at higher levels than might be expected given Iran’s average levels of educational attainment and general economic development. Over the next decade, should Iran’s economic recovery gain momentum, the average household size will likely decrease, particularly as the number of single-person households rises again. Market research has shown that singles see one-stop shopping as less appealing because it requires more time and pre-planning.

Second, the global shift away from one-stop shopping is tied to growing consumer demands for convenience. In developed economies, people are increasingly busy, and two working parents often lead households, a circumstance that will become more common in Iran. This trend has led consumers to rely more on local convenience stores and to purchase groceries online. At the same time, low levels of chain store market penetration means that most Iranians continue to rely on local neighborhood stores for their daily needs. In cities where mobility is limited by traffic and poor transport links, these small shops remain far more convenient than the one-stop shopping outlets. Add to this the rapid uptake of e-commerce among Iranian consumers and the trends suggest hypermarkets may be at their most appealing right now.

Finally, consumers worldwide are insisting on a greater effort by their retailers to engage at a local or community level. The success of retailers such as Costco, Whole Foods Market, and Trader Joe’s—each of which has cultivated a reputation as a friendlier and more ethical retailer—has had a significant impact. The importance of community engagement is particularly acute in Iran, in which retailers are competing with the traditional bazaar, a unique retail space in which market transactions are deeply tied to social exchanges. Iranian consumers remain connected to the idea that purchasing a good is best done via a trusted vendor with whom a personal rapport exists.

To address these issues, Hyperstar has taken numerous steps. It has opened its locations as anchor properties within larger shopping mall developments so that a trip to the grocery store can be part of a larger retail experience. It has also begun to roll out home deliveries to better serve people’s daily needs. Furthermore, it has used in-store activations like food tastings and special events to engage at a community level. Company documents also outline a plan for Hyperstar to eventually roll out smaller “market” stores to serve neighborhoods.

Nonetheless, the combination of these trends means that while Iran’s retail market is far from saturated, Iranian and international retail companies developing entry or expansion plans for the market need to keep up with the times. Rather than replicate the business models from twenty years ago, retailers in Iran and their international partners should adapt the current best-in-class thinking about how to serve consumers. A “channel convergence” is needed in which retail brands span hypermarkets, convenience stores, discounters, and e-commerce platforms to create a multifaceted consumer offering. This is where Iran’s domestic chain stores could hold immense untapped potential. With new branding and better merchandising, these stores may be ideally positioned to benefit from the coming changes in Iranian consumer preferences.

While conventional wisdom might suggest creating a “modern” Iran will require building the biggest and brightest supermarkets possible, to be truly cutting edge, smaller stores may be the key to success.

Photo Credit: Thomas Christofoletti

To Save the Iran Deal, Unleash the Auditors

◢ The Obama administration is weighing its final possible measures to strengthen the Iran Deal before President Trump has a chance to make his mark.

◢ Improving transparency in the Iranian economy would have the most immediate impact on the continued viability of sanctions relief. US policy must make it easier for global consulting and auditing firms to work in Iran.

As President-elect Trump begins to assemble his cabinet, the initial panic around the survival of the Iran Deal has given way to discussions about how exactly deal supporters can work to preserve its achievements. With several vocal opponents of the deal now suggesting that the JCPOA agreement may not be slated for immediate destruction, a window has opened to strengthen and protect the processes of implementation.

In Washington, there is just enough time for a few final executive actions to be taken in order to support implementation of the Iran Deal, and the Obama administration is currently weighing its options. The administration must strike a balance. It must take significant action to signal to Iran, Europe, China, and Russia that the deal continues to be viable, while not doing anything drastic enough to provoke a harsh reaction by the incoming Trump administration.

Perhaps this is exactly why unthreatening consultants, accountants, and auditors might be the unexpected saviors of the Iran Deal. Ten months after Implementation Day, Iran’s economy remains opaque, and the many large investment opportunities that have reached MOU-stage remain contingent on further due diligence and compliance work to ensure all parties, including elusive financiers, are ready to proceed with the transaction.

As it stands, many of the world’s largest advisory companies remain unable to service clients in Iran, leaving too few advisors on the ground working to bring transparency and strategic clarity to both Iranian and international business leaders and investors. For every global management consultancy, accountancy, or communications firm that has been able to establish an Iran desk, two others remain stuck on the sidelines. The challenge is that current US general license policy, in particular General License H, is too ambiguous for the purposes of enabling many major multinational companies to create an Iran market offering that fits within larger corporate structures. Issues around governance, support services, intellectual property, technology, and billing are all unaccommodated under general licensing, making it arbitrary as to whether key stakeholders in a company will decide that it is feasible to offer services to Iran. Some firms, uncomfortable with the ambiguity in General License H, have applied to OFAC for specific licenses, but long delays and difficult dialogue mean that few companies succeed with this channel.

To make an immediate and lasting impact on European efforts to establish economic ties with Iran, thereby increasing the flow of investment anticipated following sanctions relief, the Obama administration must create a new general license with more expansive accommodations for services related to improving transparency in the Iranian economy. Apart from a handful of small service providers, Iran is devoid of professional accountants, management consultants, and public relations advisors that are able to work to international standards. Unleashing the “Big Four” in Iran could be a way to keep the four horsemen of the Trump administration at bay. There are three key reasons why a new general license could fundamentally improve the pace of implementation and the viability of the Iran Deal.

First, such a general license would radically improve transparency in the Iranian economy. Some experts, such as former UK Ambassador to Iran Sir Richard Dalton, have recently called on authorities to develop a “positive list” whereby companies can ascertain “the ownership and control of Iranian state entities, including entities where there is no IRGC (Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps) presence.” Such a list would be all but impossible to institute under the Trump administration, and it is unclear whether it is even the place of any government to judge the suitability of Iranian companies for partnership. However, if a wider range of companies were able to conduct due diligence work in Iran, a potential positive list would emerge more organically. As companies are vetted by international consultants hired by strategic and financial investors, the findings will become part of the collective knowledge of the business community. It is already commonplace for business leaders to ask one another whether a given company in Iran has a “clean” reputation (Do they run parallel books? Who are the true shareholders?). While client privilege will prevent consultants from disclosing their due diligence findings directly, business leaders who do pass muster would almost certainly exercise their prerogative to market this fact widely. Word-of-mouth would combine with the commercial value of a verified reputation to create a new dynamic in the business community where transparency is paramount.

Second, getting more due diligence experts into Iran would improve the viability of the Iran Deal by diminishing the criticism of anti-deal groups. Since Implementation Day, think tanks like Foundation for Defense of Democracies and advocacy groups like United Against Nuclear Iran have had to adapt their messaging. Acknowledging that attempts to “name and shame” companies that work in Iran no longer deter major multinationals from exploring the market, these groups have recently focused on highlighting that Iran trade and investment is “risky business” and that due diligence must be taken very seriously prior to any actual engagement. The approach makes sense given that due diligence is difficult to complete in Iran—these groups are reminding companies that it is foolhardy to make investments based on leaps of faith. Should world-class due diligence become a more easily accessible service in Iran, leaps of faith would become unnecessary, and this criticism would lose its resonance. Moreover, if globally-reputable advisory firms are able to audit ongoing compliance with regulations, then US and EU authorities would be under less pressure to police whether the implementation of the Iran Deal is benefiting parties such as the IRGC.

Finally, any step to increase transparency in the Iranian economy is likely to help assuage longstanding concerns in the banking community. Major European banks remain unwilling to transact with Iran, but concern over US sanctions is not always the predominant issue. European banks are even unwilling to engage in sanctions-compliant transactions because of wider risk concerns. In effect, Iran is still seen as an economy in which ownership is shrouded and in which money moves freely between the legitimate and illicit sides of the economy. Because so few Iranian companies have undergone significant due diligence, there is very little to counteract this impression. In other markets, major banks rely on the evaluations of the Big Four auditors (EY, PWC, KPMG, and Deloitte) or the Big Three credit rating agencies (Moody’s, Standard & Poor's, and Fitch Ratings) to guide the appropriateness of engaging with particular client transactions.

As in these other markets, Iran needs a holistic approach to compliance where no one entity assumes too much risk for signing off on major transactions. The decision to provide banking services or to facilitate a transaction should depend on input from the compliance department of the client (such as a major multinational corporation), the compliance department of the bank, and the external compliance experts who have conducted due diligence on the Iranian counterparty (given that Iranian firms do not have robust internal compliance functions).

In this way, while Iranian banks work to institute sector-wide reforms including adherence to FATF guidelines, the advisory services of the Big Four, Big Three, or other respected firms could play a critical role in raising the comfort level of major banks in engaging in transactions—at least on a case-by-case basis. Given how important individual transactions by European multinationals such as Airbus, Renault, Total, or Siemens will be to the overall sentiment around the Iran Deal, even a move to increase case-by-case acceptance of Iranian financial engagements could have a major impact.

As US regulators have set expectations regarding the parameters of acceptable commercial activity with Iran by both US and non-US persons, and the requirements for due diligence therein, it behooves regulators to empower businesses to meet those expectations to the fullest ability. In the limited time that remains before the uncertain leadership of President Trump, the Obama administration should strengthen the Iran Deal by unleashing the auditors.

The Overblown Fear of Iranian State-Owned Enterprise

◢ The IRGC reportedly controls up to 40% of Iran's economy. The scale of these holdings is in line with historical levels of state ownership seen in OECD countries.

◢ US policy should apply a more nuanced approach to state-owned enterprise in Iran, and induce the market forces that are already proving to support privatization.

When the first IPC contract was awarded to Setad, an entity with ties to Iran’s Supreme Leader, critics of the nuclear deal saw confirmation of their worst fears. In their view, sanctions relief was always bound to enrich elements in the Iranian state, fueling conflict in the region.

As scholar Alex Vatanka writes in a recent piece for Foreign Affairs, the awarding of the IPC contract was a concession by the Rouhani administration to a wave of pushback by the extensive military-industrial complex mostly controlled by the Iran Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). As Vatanka argues, the Rouhani administration is engaged in the “thorny process” of “compromising and whenever possible co-opting the political and economic interests of the hardliners.”

This “thorny process” is part of the larger effort of privatization in the Iranian economy, to which the Rouhani administration is vocally committed. As such, it is important to not see politically-necessary compromises as failures. On the contrary, slowly undoing the grip of Iran’s military-industrial complex on the economy requires a much more nuanced understanding of state-owned enterprise, not just by the Iranian stakeholders, but also by Western business leaders and policy makers.

Since Implementation Day, there has been little effort to examine the actual mechanics of business on the ground in Iran, particularly between Western multinationals and state- owned enterprises (SOEs). One of the few assessments is a recent report by the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD), a think tank which opposed the Iran Deal. The FDD report offers an attempt to unpack the role of the IRGC in Iran’s economy in a detailed manner, looking at the history of actual acquisitions in Iran. In line with FDD’s advocacy, the report is skeptical of Iran’s capacity for reform:

Even as Iran welcomes forging strategic trading ties – inviting foreign capital and technological investment to enhance Iran’s export capabilities – it ultimately subordinates these openings to national security and foreign policy goals. The IRGC is the guarantor of this objective.

While the report ends with the expected call for additional sanctions, it remains a good case study in how a convoluted and stubborn understanding of the IRGC has been crafted in Washington, impacting how US policy is applied towards Iran’s economic recovery.

Part of the Western reaction to state ownership in the Iranian economy is a product of the neoliberal mindset. Beginning in the 1970's, Western governments spent four decades slowly untangling the state from the economy. Policymakers and business leaders in the West tend to see state-ownership in their own countries as not only undesirable, but also economically and socially irresponsible. This is particularly true in the United States, where state-owned enterprise is essentially non-existent.

American observers of Iran would do well to consider that mechanisms of political economy are complex. Ownership is easily conflated with the idea of control, but ownership is just one mechanism by which a state can influence the decision-making of commercial actors. Looking to the United States, some of the country’s largest employers, such as publicly-traded firms Boeing and Lockheed Martin, are hugely dependent on federal budgets and underlying political decisions. National security posture is equally as consequential to the economic well-being of households in an industrial city such as Everett, Washington as it is in Karaj, Iran.

In Europe, the connections between commerce and the state persist, reminding us that state ownership was once the economic norm. The push for privatization in Europe, a politically-fraught process, did not begin in earnest until the 1980's. It wasn’t until 1998 that Europe saw the total annual value of privatizations peak. Today, European governments retain significant ownership in their countries' major multinational corporations. For example, France has ownership in EDF and Airbus, Germany in Volkswagen and Deutsche Telekom, and Italy in Enel and Eni. It is also worth considering that while central government control of companies in Europe has declined, it persists at local levels. Today, only a handful of enterprises in Germany are controlled by the federal state, but according to PWC, nearly 15,000 companies are owned by local municipalities, a form of state ownership that goes unconsidered.

Overall, the 34 OECD countries boast 2,111 fully or majority-owned state-owned enterprises (SOEs) valued at USD $2.2 trillion dollars. Looking at basic averages, this is equivalent to 62 majority-owned SOEs per country with an average total value of USD $64 billion dollars. By way of comparison, the FDD report identifies “at least 229 companies with significant IRGC influence, either through equity shares or positions on the board of directors.” This figure includes firms in which the IRGC does not have a majority stake. Whether or not it is precise, there is no doubt that the IRGC owns some of Iran’s largest conglomerates, and it is widely agreed that the military-industrial complex accounts for 20% to 40% of the Iranian economy.

If we generously assume that the IRGC controls 40% of Iran’s economy (as measured by GDP), this amounts to roughly USD $150 billion in value. Using data compiled by The Economist, we can draw comparisons to key Western economies. The total value of state ownership of firms in France (including minority stakes) is USD $280 billion dollars, which is equivalent to 10% of GDP. In Italy it is USD $230 billion or 11% of GDP. In Germany it is $130 billion or 4%. In Japan it is USD $480 billion or 10% of GDP. In Sweden it is $160 billion or 30% of GDP.

In short, the IRGC is about as entrenched in Iran’s economy as the Swedish state is in Sweden’s economy. While state ownership in Iran extends beyond the IRGC to include other state-affiliated groups, it is evident that proportion and value of ownership is not as drastically different when compared to that of advanced economies.

Moreover, the scale of this ownership should be evaluated in historical perspective. Many of Europe’s leading industrial companies were forged in wartime economies that were the first installations of the “military-industrial complex.” That currently 20% to 40% of the Iranian economy can be designated as part of such a complex is in line with the norm for Western political economy in the twentieth century. Therefore, while at this point in time there are perhaps numerous companies with IRGC ownership, we should be able to imagine a time in the future when the number will decrease. Furthermore, we should take stock of the forces which may drive the relevant trend.

It is also important to draw comparisons across more comparable geographies. State ownership remains a mainstay of emerging economies around the world. High levels of state ownership can be measured by looking to the state shareholdings of the ten largest firms in the BRIC markets of Brazil (50%), Russia (81%), India (59%), and China (96%). In short, state ownership, whether or not it is economically prudent, is far more normal than many Western policymakers readily admit.

Critics maintain that the case of Iran is somewhat different. Those skeptical of engaging Iran economically argue that Iran’s industrial complex is deeply tied to forces such as the IRGC, and that the economic proceeds from IRGC-owned entities could be directly contributing to Iran’s foreign interventions and domestic repressions.

These concerns are broadly valid. The lack of transparency among state-owned enterprises raises serious concerns for any foreigners seeking to do business in Iran. But the concerns are overblown when they are used to dissuade engagement with the Iranian economy. The West determines whether to sustain state ownership in its own companies, or whether or not to engage with a Chinese or Indian SOE on a case-by-case basis. When considering Iran, however, state enterprise is raised as a reason for the blanket rejection of economic engagement, drawing often tenuous links to military activity. There are two reasons why state-ownership should not be used to justify the continued isolation of Iran’s economy.

Firstly, state-ownership exists as a spectrum. When we look at Iran’s industrial complex, it is important to mark the difference between a company being a direct enabler of illicit activity, and one being merely imbricated within a political economy that produces such effects. For example, when looking to Iran’s banking sector, the FDD report goes so far as to argue that “the distinction between IRGC-owned, IRGC-linked, and non-IRGC banks is insignificant.” But this is patently false. For example, the report indicates that the IRGC maintains ownership positions in twelve companies listed on the Tehran Stock Exchange. While this ownership may mean that the IRGC benefits financially from any increase in the share price driven by investor demand, it also means that the companies are beholden to a wider array of shareholders. The governance of a public company neutralizes some of the risks associated with IRGC ownership. Pushing more of the IRGC companies towards public share offerings may enhance the absolute value of the IRGC holding, but it would reduce the relative value (and influence) of the holding when compared with what is controlled by public shareholders.

Secondly, state-ownership is conditional on market forces. The FDD report offers a compelling example from the automotive industry. In June, 2016, the IRGC “sold its shares of Bahman Group, the country’s third-largest carmaker”, most likely because “it understood that the company could not sign contracts with foreign companies if the IRGC retained ownership.” In this way, a key outcome of sanctions relief for Iran-- increased foreign investment--is changing the incentives around state-ownership. What the FDD report leaves out is that Bahman Group was subsequently acquired by Crouse, a highly-regarded privately-held car parts manufacturer, demonstrating how consolidation and M&A activity can drive privatization in mature sectors. Had Bahman Group remained in IRGC control, it would not have been able to compete with Iran’s other carmakers, which are on the cusp of introducing new models on the back of new joint ventures with foreign partners.

By adopting a more nuanced view of state ownership in Iran’s economy, sensible policy could be devised to induce the market forces necessary to drive further privatization. Unfortunately, many in Washington who will read the FDD report are unlikely to properly configure the facts. The notion that the extent of state-ownership can be modulated or eliminated by relying on market forces will not resonate in the case of Iran, despite the compelling evidence from other countries. This is the great irony. A neoliberal doctrine that vilifies state ownership keeps lawmakers and policymakers in the US fixated on crippling the Iranian economy. However, the solution could be to simply trust that the influx of foreign investment will change incentives as a more competitive and freer marketplace emerges.

Perhaps this is why the FDD report ends with what seem to be contradictory recommendations. On the one hand the report calls for the US to “impose non-nuclear sanctions on individuals, entities, and entire sectors of the economy involved in illicit activities.” On the other hand, the authors suggest that “companies should avoid trade and investment in Iran,” while also conceding that many firms are choosing to enter the market. At the very least, the authors note, these companies should take special care in due diligence and to “require certification from Iranian partners that they are not IRGC-linked.”

Washington needs to decide whether it is going to continue with the contradictions or craft a more sensible policy. Coming to that decision will no doubt be a thorny process.

Photo Credit: Wikicommons

Why the Iran Deal Will Survive the Trump Presidency

◢ The Trump presidency poses considerable risks to the full implementation of the Iran Deal, but is unlikely to threaten the deal's survival as some have suggested.

◢ Trump's interference in the deal will be constrained by domestic politics, Russian strategic interests, and European lobbying.

This article was originally published in LobeLog.

Trump’s triumph is sending shockwaves through the foreign policy community, particularly among supporters of the Iran nuclear deal. Reuters has already reported that Trump’s election puts the Iran Deal “on shaky ground.” Richard Nephew, a former State Department official who was involved in the nuclear negotiations, told Reuters, “Say goodbye to the Iran deal.” Daryl Kimball, director of the Arms Control Association, which supported the Iran Deal, noted to The New York Times that it was unclear whether Trump “would deliberately or inadvertently take actions that unravel that agreement.”

Views from Iran echo this pessimism, as political commentators note that Trumps election could empower Iran’s hardliners. Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif has sought to temper concerns by arguing that the “most important thing is that the future U.S. president sticks to agreements.”

Trump’s win no doubt introduces uncertainty into the already complicated status of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). But the notion that Trump can or will single-handedly dismantle JCPOA overstates his likely power as president. Three factors will constrain his ability to unravel the Iran deal: the relatively low importance of Iran in the current landscape of American politics, the essential security implications of the Iran deal for Russia, and the economic ambitions of Europe.

Trump’s Priorities

Trump will arrive in the White House with little pressure to take immediate action on Iran. Although Trump did use the Iran deal as a means to impugn both Hillary and Obama, his vocal opposition to the deal probably had little to do with his electoral success, as other races show. Republican Senator Mark Kirk of Illinois, one of the most vocal opponents of the JCPOA, lost his seat to Democrat Tammy Duckworth, a deal supporter.

Although foreign policy was important in the election, it was not for the typical reasons, and this may be a saving grace for the deal. According to data from the Pew Research Center, 89% of Trump supporters highlighted terrorism as a “very important” issue, while 79% considered foreign policy to be “very important.” In both categories, the Trump supporters considered the issue more important than did Clinton supporters (74%, 73%). Although these figures might suggest that the electorate expects Trump to take action against what Trump has called a “terrorist state,” it is important to remember the tenor of the foreign policy debate in the election and what Trump came to represent.

For the Trump camp, the overall posture of foreign policy amounts to something of withdrawal. This may be reflected in the same Pew dataset—54% of voters believe Clinton would make “wise foreign policy decisions” versus just 36% for Trump. In some sense, Trump supporters may be unperturbed by his lack of foreign policy skills because they want him to make fewer foreign policy decisions overall. As Max Fisher and Amanda Taub argue persuasively in The New York Times, Trump’s success in the foreign policy debate was about avoiding the complexities of actual policy, instead using foreign policy as a discussion point to highlight his appeal as a strong leader. Voters will not likely expect Trump to meddle in the details of the Iran deal and even if he did, they would have a hard time discerning its impact. Trump’s boastful proclamations may suffice for his supporters, leaving him with little obligation to engage the thorny, multilateral nature of the Iran deal at the level of actual policy.

Security Imperatives

Although Iran and Europe have principally depended on the United States to set the pace and parameters of sanctions relief, particularly as US sanctions remain in place, the matter of implementation is actually somewhat separate from the matter of the deal’s viability. Those concerned for the Iran deal’s survival argue that President Trump will block sanctions relief for Iran, playing into the hardliner narrative that the US is obstructing the deal and thereby enabling Iran to back out.

However, the JCPOA’s promise of sanctions relief is of primary importance only if Iran and the United States remain the two pillars of the deal’s viability. With a Trump presidency, the deal will be defined by its more fundamental dimension of security. One of the principal outcomes of the JCPOA was to ameliorate Iran’s security dilemma. Iran had been on the back foot, wary of military intervention from the United States, Israel, and Saudi Arabia on the pretext of its proliferation threat. The Iran deal was conceived as an arms control agreement, despite its current billing as a kind of economic pact.

If security is the chief justification of the deal for all parties, then the new pillars of the deal are Iran and Russia. For Iran, the JCPOA eliminated an urgent threat of attack by Israel and/or Saudi Arabia by removing the only globally acceptable pretext for such an attack—a proliferation risk. The knock-on effects have freed up Iran’s security apparatus to take a more aggressive security posture in the region, particularly in Iraq and Syria. The notion that this new posture proves that the Iran Deal empowered Iran’s security apparatus is worthy of its own debate, but at the very least it has enabled Iran to align with Russia and mobilize in the theater of conflict in Syria. Russia was a key party in the Iran deal negotiations. Russian strategic interest in the JCPOA is not economic—Iranian companies remain generally uninterested in working with Russian firms, and Russian foreign policy is markedly uninfluenced by economic prerogatives as the ineffective imposition of Western sanctions shows. Realistically, Russian support for the deal was about enabling Iran to be a more active geopolitical actor in the region, uniquely free from obligations to toe the US line.

For President Trump, Russian interests may pose the biggest barrier to ripping up the deal. This is true irrespective of any special Trump relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin, which is beyond the scope of this analysis. If Trump were to rip up the deal, Iran would need to take retaliatory action in light of domestic politics, perhaps by (at least symbolically) restarting its nuclear program. If Iran were to do so, it would put the country back on the agenda for military intervention by Israel or Saudi Arabia. Both states would be able to quickly rally support among US lawmakers for any such move—the image of Iran as a nuclear threshold state persists in Washington. But if Iran were drawn into a direct military conflict with any of its neighbors, its ability to align with Russia in the Syria conflict would be seriously compromised.

Russia, already overstretched in Syria, needs Iranian collaboration to keep Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad in power. Russia has a strong incentive to keep the current balance of power in the region intact, and the Iran deal is part of that balance. Russian enticements should be sufficient to keep Trump contained regarding Iran, while also shoring up Iran’s commitment to the deal through outreach to stakeholders in the IRGC and around the Supreme Leader. In short, the question of faltering implementation during a Trump presidency is unlikely to override the security dimension of the JCPOA. Tearing up the Iran deal means conflict with the nascent Russian-Iranian coalition.

Then There’s Europe

Stuck in the middle of this scenario is Europe. The European interest in the Iran deal is largely economic. Economic development in Iran benefits European economies but also supports the process of moderation in Iran that has been a key part of the political justification of the Iran deal in European capitals. As such, Europe cares more about implementation of sanctions relief than perhaps any other actor.

The Trump presidency will no doubt slow the process of implementation in the near-term. But European companies have yet to directly push US policymakers regarding the lingering challenges of doing business with Iran. Some observers in Iran went so far as to suggest that Trump’s business background will make him amenable to working with Tehran. Although this might be a leap too far, the notion that “money speaks” for President Trump could hold water. To the same extent that Trump’s arrival in Washington discombobulates the foreign policy community, it may do the same for lobbyists. Multinational businesses have an opportunity here to exert influence in the advocacy vacuum if they can get the right mechanisms in place. Given the first and second points made here, the bar will be relatively low: prevent interference in the deal.

Perhaps this explains the brave words already coming from key European actors regarding Iran. French oil giant Total, which this week announced a major investment in Iran’s gas industry, has indicated that “the election that took place in the United States does not change anything” regarding its projects in Iran. Other European industrial firms are likely take a similar view—after all a Clinton administration would have posed its own challenges regarding the political and compliance risks of engaging with Iran.

Importantly, Iran deal implementation is the responsibility of a dedicated group of civil servants at the State Department and the U.S. Treasury, and these individuals are unlikely to be moved from the Iran file, even if Trump’s secretary of state is a vocal opponent of the deal such as Senator Bob Corker. But the new administration’s foreign policy posture will probably sap the ability of the State Department and the U.S. Treasury to actively work on implementation issues through outreach.

So, although the deal’s survival may not be under threat, the Trump impact on implementation will certainly limit the scope of its success. To address implementation, outside actors will need to take on greater responsibility to define challenges, devise policy solutions, and drive advocacy. Selling-in policy suggestions to the Trump administration might become the true “art of the deal.”

In some ways, it is saddening to once again return to a “great-game” type discussion of US-Iran relations in the Middle East, and to suggest that better lobbying might be a way to mitigate the impact of Trump’s presidency. But Trump’s ascendency is merely a step backwards on a journey that has been halting and complicated from the outset.

Photo Credit: Wikicommons

Airplanes, Oil, Elections, and Zeno's Paradox in Iran

◢ News regarding the Airbus deal, the gas industry, and the US election mark progress in Iran's frustratingly slow post-sanctions development.

◢ But the recent increase in the incremental steps taken for Iran's economic growth should be encouraging, as the math behind Zeno's Paradox demonstrate.

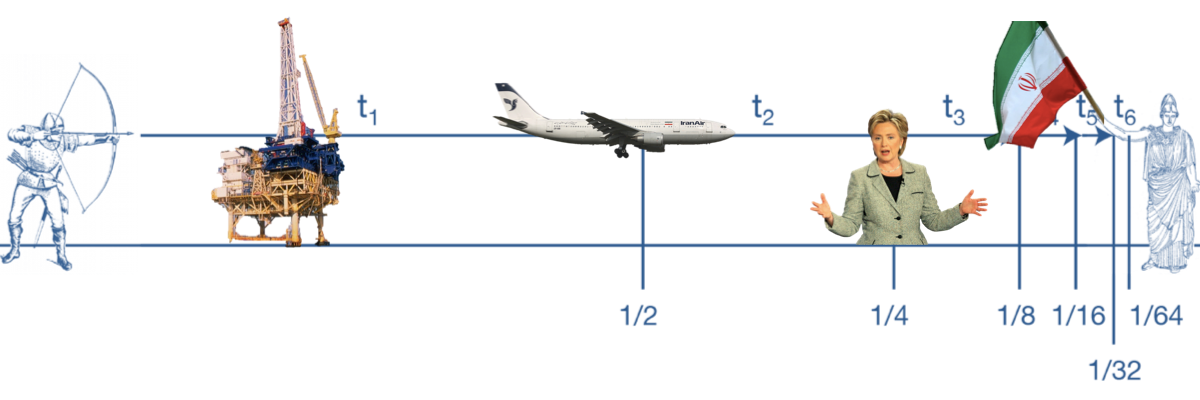

Zeno of Elea was an Ancient Greek philosopher most famous for his four paradoxes on the relationship between space and time. The most famous “Zeno’s Paradox” is the “Dichotomy Paradox.” Imagine you wish to travel from A to B. In order to reach your destination, you will need to walk half the distance. You will then need to walk half of the remaining distance (a quarter of the total distance), and then half of the remaining distance (an eighth of the total distance), and so forth. Continuing in this manner, as the basic math shows (½ + ¼ + ⅛ …), it would take an infinite number of steps to reach point B.

On Iran’s journey from A to B, from sanctions relief to economic resurgence, the Iranian and European business communities have been waiting for three key milestones: Iran’s acquisition of its first new airliners, the entry of the first international oil company to Iran, and the conclusion of the seemingly everlasting US election. There have been developments in each area this week.

First, Tim Hepher and Parisa Hafezi at Reuters report that Airbus has made progress in the effort to secure financing for its deal to sell 118 planes to Iran Air. However, the lease finance, which may come via Dubai, would only cover the first 17 planes.

Second, Benoit Fauçon at Wall Street Journal was the first to report that France’s Total and China’s CNPC would be the first international oil companies to make a post-sanctions investment in Iran’s gas industry, working with Iran’s Petropars to develop the South Pars gas field in a USD $6 billion deal. However, the signing ceremony was only for a Heads of Agreement, and the “deal is a draft that still must be completed over the next six months” according to Iranian officials.

Finally, we have passed election day in the United States, and after months of uncertainty, Iranian officials and the business community now know that Donald Trump will lead the United States for the next four years. While the outcome is concerning due to his outspoken criticism of Iran, at the very least companies can begin to evaluate political risk more concretely as they weigh investments in Iran and elsewhere. However, the nature of the US election and the discourse between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump meant that there was no substantive discussion of Iran policy by either candidate. While the Iran-focused personnel at the State Department and the U.S. Treasury are unlikely to change, it will likely take several months for the new Trump administration to signal its overall approach on implementation of the nuclear deal and related issues.

It seems, therefore, that in each instance where there is progress in Iran’s post-sanctions agenda, something like Zeno’s Paradox remains in effect. For every milestone reached, another remains frustratingly far away, and the ultimate goal of profits and economic growth seem tantalizingly out of reach.

Part of the problem is one of perception, and here, Zeno is once again instructive. His “Arrow Paradox” describes the relationship between motion and time. If you observe an arrow in motion at a single point in time, it will appear motionless. Continuing in this manner, if the arrow is observed at every instant on its journey, it will appear motionless at every instant. Motion, therefore, would seem impossible.

In some ways, the arrow paradox describes the problem of perception and expectation around Iran’s economy. The tendency is to observe the market at a given instant, and to see banking challenges, reputation risk, and political uncertainty as barriers that have prevented trade and investment almost constantly. It might seem that no progress is being made.

The trick to understanding Zeno’s paradoxes is the same as the trick to seeing the progress in Iran’s economic recovery. Worrying too much about how to take the next step on the journey from A to B and about the challenges that presently make that next step difficult, make us blind to the importance of changes in momentum.

As the news from Airbus, Total, and the US Election demonstrates, Iran’s economic recovery is gaining momentum. Key milestones are being reached more quickly, even if the incremental steps are smaller. While the JCPOA nuclear deal took us halfway from the journey from economic isolation to economy resurgence, subsequent steps, represented by the actions and achievements of particular ministries, companies, or individuals, will be smaller. But these steps are now occurring more rapidly. As Brian Palmer explains in Slate, the trick to solving the paradox is to make “the gaps smaller at a sufficiently fast rate.”

This is exactly what is happening in Iran to solve the country's economic paradoxes. A resurgence once considered impossible is slowly coming to fruition.

Iran's First "Airport City" Blueprints a New Way of Doing Business

◢ The master plan for IKIA Airport City is one of the most ambitious in Iran and will require USD $50 billion in investment to achieve.

◢ Creating an airport city is not just about new transport links, but also about creating new models of collaboration between state and private actors.

Travelers to Tehran often wonder why Iman Khomeini International Airport (IKIA) was built so far from downtown Tehran, requiring at least an hour's drive and often much more given the city's notorious traffic. Many Iranians miss the ability to fly to international destinations from the centrally located Mehrabad Airport, from which IKIA inherited all international flights in 2007. But while Mehrabad is a 20th century airport built to serve Tehran, Iman Khomeini is built for the 21st century, with a wider range of priorities in mind. Today, airports are the key engine of economic growth for cities competing in a globalized economy and in the last decade airport development has become a central focus for urban planners and economists alike. The 2011 book Aerotropolis, written by John Kasarda, Director at the Center for Air Commerce at the University of North Carolina's Kenan-Flagler Business School, helped establish the concept of the "airport city." Kasarda argues that the airport deserves a more central role in how urban spaces are created. He writes, "Rather than banish airports to the edge of town and then do our best to avoid them, we will build this century's cities around them."

The master plan for IKIA includes the vision to create a world-class aerotropolis by building a city around IKIA. The Ministry of Roads & Urban Development has positioned IKIA to investors as "an international crossroad connecting north to south and east to west" which "makes it profoundly eligible to evolve as a regional hub, leading to [the development of ] an Airport City or an Aerotropolis." This is precisely why the airport was built so far from Tehran; it needed room for a new city to grow. Moreover, the airport was meant to connect geographies, and is accessible from Semnan Province in the east, Qom and Isfahan provinces to the south, Markazi Province to the southwest, and Alborz and Qazvin Provinces to the West.

Our firm, Rah Shahr International Group, spent several years developing the master plan concept for Iran's first such airport city, the Imam Khomeini Airport City. In this plan, the airport becomes a nucleus around which commercial centers, residential zones, and transport infrastructure would be organized. The IKIA Airport City will hopefully decentralize a good portion of Tehran's congestion by moving many offices and businesses to the new mega-site. We estimate that IKIA Airport City will require USD $50 billion of investment.

The scope and size of the IKIA project echoes Kasarda's view of airports as "components of large technical systems" that work like machines to create logistical efficiency and economic productivity. In the technical system for IKIA, there will be four major zones, an Aviation Zone (2,800 hectares), a Free Economic Zone (1,500 hectares), a Special Economic Zone (2,500 hectares), and a Mixed-Use Zone (7,000 hectares). Each zone will in turn house different facilities such as light industry, hotel and convention spaces, warehouses and logistics centers, commercial offices, and even public parks. To work effectively, these zones will need to be linked by road and rail to Tehran and Iran's four corners in a "smart" transport network. The main highway from Tehran to Bandar Abbas (with access to Isfahan and Shiraz) passes by IKIA to the East. Saveh Highway passes to the West. In terms of rail access, the extension of the Tehran metro network to a new terminus at IKIA, which is nearing completion, reflects a positive first step. The proposed Isfahan-Tehran high-speed bullet train will connect through IKIA.

Clearly, the master plan for IKIA is one of the most ambitious in Iran, and it will therefore require Iran to innovate new ways of fostering cooperation and economic development between a wide range of stakeholders. This may be the most important legacy of the airport city project. Airports and their surrounding developments rely on enterprise zones and tax abatements to attract tenants, urban development corporations to manage the project delivery, and public-private partnerships to fund the construction of critical infrastructure. As anthropologist Brenda Chaflin explains about the airport in today's globalized world, "Redesigned and reimagined, the airport is... a site of contestation and collaboration between a plethora of state overseers and the private sector, including architecture and construction firms, investors, and development banks." Getting these different groups to cooperate will be a significant challenge, but it may also be the critical outcome for Iran's long-term economic success. IKIA can serve as a testbed for developers, contractors, and investors from both Iran and abroad.

We can already see evidence of new collaborations at IKIA. In 2015, the Ministry of Roads & Urban Development established the IKIA Airport City Company to serve as the contracting party in public-private partnerships around airport city development. Through this entity, the government negotiated a joint-venture with French construction firm Bouygues and French airports operator Aéroports de Paris (AdP) to construct a new passenger terminal in a USD $2.8 billion deal that would increase airport capacity to 20 million passengers per annum in the first phase. A possible further three phases have been planned that would take the airport though 90 million passengers per annum in total capacity.