In Boeing, Airbus Negotiations, Iran Air is Flying Solo

◢ Following the approach of most Iranian state owned enterprises, Iran Air has not engaged outside counsel for its negotiations with Airbus and Boeing.

◢ Hesitation to work with international law firms may be impacting the speed and effectiveness of negotiations.

The recent announcement that US regulators have given their approval for the sale of Boeing and Airbus aircraft to Iran Air has been met with great enthusiasm. Officials at Iran Air have stated that they expect to receive the first Airbus airliners early next year. The news is remarkable on a number of levels, as the Boeing and Airbus agreements have been seen by many to be the linchpin deals that would finally help raise the comfort level of international banks to transact with Iran.

It is also noteworthy that Iran Air has negotiated the deals without the advisory of an international law firm. Despite the fact that most airlines rely on outside counsel to help navigate the aircraft acquisition process, and that international law firms are itching to increase their presence in Iran, Iran's national carrier has followed the approach of most Iranian state-owned enterprises and forgone outside legal counsel in the negotiation of these commercial agreements. Instead, the company relies on its in-house lawyers, as well as on legal experts at the Ministry of Roads and Urban Development, which oversees both Iran Air and the Civil Aviation Organization.

Iranian state enterprises avoid engaging outside lawyers due to concerns regarding security, political sensitivity, and perhaps most practically, an unwillingness to pay the fees associated with high-level international legal advice, which can often amount to millions of dollars. The few Iranian state enterprises that have regularly enlisted outside counsel are in the oil industry, where deeper pockets and an international marketplace necessitate a different approach. The National Iranian Oil Company has been advised by Eversheds and the National Iranian Tanker Company has worked with Stephenson Harwood. In both cases, briefs focused on sanctions-related arbitration.

By contrast, Iran Air’s counterparties in the negotiations, the airplane manufacturers, have a clear reliance on outside counsel. Airbus and Boeing are so large and deal with such a wide range of legal matters across so many jurisdictions, that they each rely on their won “preferred legal network” of law firms pre-approved to advise the firms. This way, internal legal teams can tap the support of particular firms that have the capabilities desirable for a given brief. Boeing works with firms such as Eversheds, Allen & Overy, and White & Case, among others. Airbus has worked with Clifford Chance, Willkie Farr & Gallagher, and DLA Piper, among others. Given the fact that Boeing and Airbus use many of the world’s top law firms, and given that partners often move from firm to firm, there have been instances where a conflict of interest has emerged between Boeing, Airbus, and their clients or counterparts. This may be one reason why Iran Air opts not to use foreign firms. As so many of the major firms have worked with Boeing and Airbus, it would be difficult to ensure that sensitive information could be kept confidential in the course of negotiations. On the other hand, having “backchannels” in complex negotiations can be an asset, but these usually work when there are longstanding relationships in place, which Iran Air does not have.

Encouragingly, the reputation of the Iran Air legal team is strong. Because state-owned firms rarely use outside counsel even within Iran, they invest in and empower capable lawyers to manage legal and contractual issues. The legal department at Iran Air is divided into two teams: local and foreign. Both teams are overseen by the Director General for Legal Affairs, whose mandate covers all airline transactions and commercial contracts, including acquisitions through purchase or lease, in addition to a whole host of other legal matters. In the Airbus and Boeing negotiations, the Iran Air legal team is supported by the Legal Bureau in the Department of Legal and Parliamentary Affairs of the Ministry of Roads and Urban Development, led by Deputy Minister Alireza Mahfouzi. This bureau has specific responsibility to supervise “the preparation and exchange of cost agreements and acquisition of financial and capital assets” for its affiliate organizations.

There is no doubt that significant legal talent is being devoted to the Iran Air acquisitions. Given the importance of these deals not only to the long-term commercial viability of Iran Air, but also to the public perception of the Rouhani administration. However, the size and complexity of the Airbus and Boeing deals, which involve not only two of the largest non-oil commercial agreements ever signed by an Iranian firm, but also the need to navigate the complexities of US and EU sanctions and trade regulations in a difficult political environment, raises questions about the decision not to use outside legal council. In some ways, the decision could be seen as emblematic of a wider challenge as Iran seeks to open its economy. Can the country afford to continue working by its own rules, or will it have to begin following the more typical practices of the global commercial environment, such as a reliance on external legal counsel? For the moment, it looks like the Airbus and Boeing deals are proceeding as planned. That is good news, because the Iranian people are expecting results. Nothing less will do.

Photo Credit: Iran Air

Limited Capital is Creating "Blocs" in Iran's Start-Up Ecosystem

◢ Iran's start-up ecosystem is dominated by the two VCs that have been successful securing foreign investment.

◢ With little competition, these VCs and their start-ups are beginning to form competitive "blocs," limiting opportunities for collaboration and innovation.

Iran’s start-up ecosystem has continued to grow and develop since it burst onto the global tech scene in 2015. Incubators and start-up accelerators, including MAPS, Avatech, and DMOND Group have established a strong presence and helped instill best-practices that borrow from those of Silicon Valley. Some of the most prominent Iranian universities, including Shahid Beheshti, Islamic Azad University, University of Tehran and Sharif University have launched or are developing their own start-up incubators.

At the heart of the incubators and accelerators, a community has emerged that helps inspire new founders through events and outreach. Iran Startups and Roshdino host regular entrepreneurial meetings where start-up veterans share their expertise with local audiences, while Hamfekr Tehran coordinates weekly networking events hosted by a different start-up every week across various cities. The local community is not totally detached from the international scene, with Startup Grind having hostedsixteen events in Tehran, and Seedstars World—a start-up competition for emerging markets—holding its second Tehran-based event this month. Several conferences held outside of Iran, such as iBRIDGES series, were created specifically to link foreign investors with the Iranian start-up scene. Publications like Techrasa and Techly collect news on the start-up scene. An ecosystem is coming together with amazing speed.

Yet, despite the positive momentum and the energy and ingenuity of Iran’s start-up founders, the ecosystem is not immune to the larger challenges of the Iranian economy. Sanctions-related constraints and uncertainty around the corporate legal and policy framework for early stage investments obstruct local and foreign investors. This introduces risk above and beyond the inherent uncertainty when investing in a nascent sector where business plans are speculative and there have yet to be any IPOs or exits.

Nonetheless, capital has begun to follow into the eco-system, with a handful of adept foreign firms making early-stage investments. The largest activity has come from Pomegranate Investment, a Swedish fund that has raised EUR 60 million earmarked for investments in tech and consumer-focused sectors in Iran. Pomegranate has invested in Sarava Pars, a VC fund with investments in Avatech in addition to start-ups including Digikala (Iran’s answer to Amazon) and Café Bazaar (an Android marketplace).

Competing with Sarava is Rocket Internet, a publicly traded German company that replicates successful online businesses and adapts them to emerging markets. Rocket has four start-up ventures currently operating in Iran. Some of these are direct competitors with indigenous start-ups, such e-commerce site Bamilo and Snapp, a taxi app. The entry of Rocket into the Iranian market in 2013 had a positive effect in jump-starting local entrepreneurs by enticing them to move quickly with their own ventures to not only fill remaining market gaps but to also create competitive alternatives to the apps Rocket was launching.

Sarava and Rocket have played a major role in fostering and funding the start-up ecosystem in Iran, but the early dominance of these two players may become a liability as the Iranian ecosystem seeks the next level in its development.

While Sarava has gained an international reputation, based on its early success investing in Iran’s most promising ventures, its success has meant that it receives the lion’s share of attention from foreign investors looking for exposure to early-stage investments in Iran. Meanwhile, smaller and less established VC funds are overlooked and have yet to raise significant foreign capital. Even with Rocket’s track record, many treat Sarava as though it is the only game in town.

Subsequently, the concentration of capital and market share within the portfolios of the two biggest and competing players in Iran’s start-up scene has led to a situation that more or less prohibits collaboration among different ventures. While many investors are warned to heed domestic politics when looking to invest in Iran, the start-up ecosystem is rife with politics of its own. Many of the start-ups funded by Sarava and Rocket Internet compete directly for market share. This makes it difficult for non-competing ventures on either side to collaborate where synergies in technology development or marketing might be possible.

Given the impact on the ecosystem, founders are calling out for more options. “Iran’s start-up ecosystem is in need of foreign investors and many more venture capital players to generate a more diversified structure”, says Pedram Assadi, the founder and CEO of Chilivery, a food delivery platform. Assadi says more funding choices are needed “to prevent the creation of start-up blocs.”

Unless more sources of capital emerge, the start-up ecosystem in Iran risks becoming comprised of inward-looking blocs of isolated start-ups, which prioritize intra-network rather than inter-network collaboration. Moreover, the concentration of capital in two blocs also affects how ideas and expertise are shared. The pool of experienced local mentors advising Iran’s start-ups is inherently small, but it is further limited when those associated with the competing blocs are effectively precluded from working with start-ups outside their network. As a result, innovation is hampered even further.

Better access to capital will change incentives. Founders will benefit when new investors are forced to seek out innovative projects in their earliest stages rather than simply deciding to pour more capital into the saturated competing networks. Competition has its merits, but reducing the control of the blocs will open the door to collaboration among ventures and would stimulate overall growth. Innovation thrives when there is a surfeit of investors always seeking the next big thing, as the successes of Silicon Valley show.

But even in the face of the current challenges, Iran’s ambitious founders are not discouraged. Until the funding environment improves, the focus will remain on the product, and many new companies are bootstrapping or using crowd-funding platforms to fund development. Hady Moslehi is one of the co-founders of Ronak—a self-funded software start-up that recently launched a team-to-team messaging app called Nested, which placed third in this month’s Seedstars Tehran competition. He insists that the “most important issue remains how to build a product that users love.” If Iran’s founders can get that right, the investors will surely follow.

Photo Credit: Avatech

What Iran's Café Culture Teaches Us About Its Consumer Culture

Coffee consumption in Iran is on the rise, but as shown in the global success of Starbucks, selling coffee is about more than just beverages. Cafés demonstrate how Iranian consumers seek places of authenticity, creativity, and community—cultural offerings that underpin commercial success.

Café culture is most often associated with the intellectual awakening of Europe in the 19th century. As Duke University Professor Jakob Norberg writes in a 2007 essay, cafés and coffeehouses were a unique public space in Europe, deeply connected to the intellectual awakening of the middle class. The café emerged as both a liberating and secure social space, a place of “vivid intellectual culture” yet also “relaxed communication.” These same qualities have made cafés in Iran susceptible to crackdowns by the authorities. The forced closure of Tehran’s Café Prague in 2013 was seen as a “significant loss for Tehran's academic and cultural life.” In the words of a patron, the café, named to evoke the intellectual milieu of 19th century Europe, “wasn't just a café; it was like home, a safe haven for us to forget all our daily troubles and burdens."

This lamentation echoes the argument of political theorist Carl Schmitt, who suggested that “coffee is a symbol of… the bourgeois desire to enjoy undisturbed security.” German philosopher Jurgen Habermas believed that “the coffeehouse is a place where bourgeois individuals can enter into relationships with one another without the restrictions of family, civil society, or the state.” As Norberg explains, “The notion… resonates with us because it is still recognizable. We have coffee, we meet in cafés, we sit down for chats with friends and acquaintances; Habermas's depiction of the coffeehouse still corresponds to an everyday practice.”

As coffee houses reemerge in the more open social and economic landscape of the Rouhani administration, the vibrant conversation among young, energetic, and creative Iranians who frequent places like the popular Sam Café corresponds to Habermas’ view of coffeehouse. At first glance, the cafés seem to offer both a liberal enclave within a larger Islamic public space—offering intellectual security and unrestricted relationships otherwise in short supply —as well as a space to reinforce socioeconomic distinctions in ways that seem typically Western. However, this view ignores the fact that coffee’s place in Iranian society predates all meaningful Westernization.

The history of coffeehouses in Iran dates back to the beginning of the 17th century, a time when coffee was more popular than tea. As relayed by social historian Rudi Matthee, coffeehouses were constructed on Esfahan’s famous Naqsh-e Jahan Square as early as 1603. The first coffeehouses in the United Kingdom were only established five decades later. The qhaveh-khaneh, literally the “coffeehouse,” was precisely the kind of open and intellectual space celebrated centuries later by the likes of Habermas and Schmitt. Matthee recounts the description of the French traveler Jean Chardin, who traveled Iran in the 1660's and 1670's:

These houses, which are big spacious and elevated halls, of various shapes, are generally the most beautiful places in the cities, since these are the locales where the people meet and seek entertainment. Several of them, especially those in the big cities, have a water basin in the middle. Around the rooms are platforms, which are about three feet high and approximately three to four feet wide, more or less according to the size of the location, and are made out of masonry or scaffolding, on which one sits in the Oriental manner. They open in the early morning and it is then, as well as in the evening, that they are most crowded… People engage in conversation, for it is there that news is communicated and where those interested in politics criticize the government in all freedom and without being fearful, since the government does not heed what the people say. Innocent games [...] resembling checkers, hopscotch, and chess, are played. In addition, mollas, dervishes, and poets take turns telling stories in verse or in prose. The narrations by the mollas and the dervishes are moral lessons, like our sermons, but it is not considered scandalous not to pay attention to them. No one is forced to give up his game or his conversation because of it. A molla will stand up, in the middle, or at one end of the qahveh-khaneh, and begin to preach in a loud voice, or a dervish enters all of a sudden, and chastises the assembled on the vanity of the world and its material goods. It often happens that two or three people talk at the same time, one on one side, the other on the opposite, and sometimes one will be a preacher and the other a storyteller.

The accounts of other travelers and scholars confirm Chardin’s description of the coffeehouses as a place of intellectual creativity and social mixing. Importantly, the coffeehouses were not confined to the imperial capital of Esfahan. Accounts speak of such establishments in Tabriz, Yazd, and Shiraz, among other cities. The coffee culture of Safavid Iran was highly developed, with characteristics that were both local and global, religious and secular. The later tendency to see café culture as a marker of Westernization, one shared today by morality authorities who often interfere with cafes and their patrons, may be tied to the role of the coffeehouse in the 20th century, when places such as Tehran’s Café Naderi became meeting places for intellectuals committed to ideological movements that originated in the West. In effect, café culture was conflated with the ideologies it was helping to foment, despite its much earlier and more local historical roots.

Today, coffee consumption in Iran is on the rise. The Customs Administration of the Islamic Republic of Iran reports that 8,000 metric tons of coffee are imported each year. Iran’s parallel import market probably means the true figure is higher. Working from the official figure, and assuming that each cup of coffee represents 7 grams, Iran’s total consumption equates to 1.1 billion cups of coffee each year (Italy, a country with 20 million fewer people, consumes a staggering 14 billion cups of coffee each year.) Importantly, just 10% of the coffee consumed in Iran is freshly ground, with the remainder being instant coffee. Nestle is the only major international brand with a significant market share, maintaining around 20% with its Nescafé instant line. The fragmented market and low overall volume reflects how tea continues to be the preferred form of caffeine consumption in Iran. However, consumption is expected to grow at the high rate of 11% CAGR until 2020, taking the value of the market to more than USD $200 million. Yet, unlocking the full commercial potential of this market is about much more than selling cups of coffee. The rise of coffee consumption will depend on the emergence of a coffee culture. New cafés are opening across Iran’s major cities. Establishments such as Tehran’s Sam Café and baristas such as Mehran Mirjani have recently garnered the attention of the global coffee community.

Overall, while the current revival of coffee in Iran is certainly a kind of re-exportation from the West (and in particular the so-called Third Wave coffee culture of Australia), it is not merely a Western phenomenon and should not be characterized as such. The implication is that companies seeking to engage in the coffee market in Iran (or the wider consumer market targeting young, urban millennials) must consider the full cultural significance of their product or service offering. Simply believing that Westernization is the most salient trend is a strategic error, particularly because of the increasing commercial importance of cultural identity.

In the past two decades, it has become clear that the world’s most successful consumer brands do more than promise effectiveness, enjoyment, or value. There is an increasing expectation for companies and their brands to address consumer demands for authenticity, creativity, and community—cultural offerings that elicit an emotional connection. Given the historical cultural significance of coffee, it is perhaps natural that one of the companies that ushered in this consumer expectation was Starbucks, whose trademark play on café culture captivated consumers. Stanley Hainsworth, Starbucks’ former VP for Global Creative explains in an interview with Fast Company:

When Howard Schultz first came to Starbucks, he wasn't the owner of the company. He joined a couple guys that had started the company. He went over to Milan and saw the coffee culture and espresso bars where people met in the morning. He saw how people caught up on the news while they sat or stood and drank their little cups of espresso. That inspired the vision he crafted from the beginning—to design a social environment where people not only came for great coffee, but also to connect to a certain culture.

The challenge for Schultz, Hainsworth and the team at Starbucks was to “create something for consumers that they don't even know they need yet.” As Hainsworth explains, consumers were looking for a new kind of place to congregate:

Howard was very wise in knowing that Starbucks was not the only company in the world to make great coffee. On the contrary, there are hundreds of other companies that can make great coffee. So what's the great differentiator? The answer is the distinction that most great brands create. There are other companies that make great running shoes or great toys or great detergent or soap, but what is the real differentiator that people keep coming back for? For Starbucks, it was creating a community, a "third place."

The lesson for the Iranian market is profound. Consumers now expect companies to show some cultural creativity at all stages of their experience—from advertising, to the retail experience, to the product itself. The ubiquity of the Apple iPhone in Iran is a strong indicator that this expectation has taken root. But perhaps most importantly, Iranians are looking for new “places” to congregate and connect.

The politicized nature of public space in Iran introduces both greater risk and greater reward for those companies willing to commit to converting “spaces into places”—but the immense popularity of sites like Palladium Mall (an upscale shopping center) or the Tabiat Bridge (a pedestrian overpass connecting two public parks in Tehran) underscores the potential. As a consequence, companies cannot simply import the branding, marketing, and product offering from Western markets. As is evident in the history of Iranian coffeehouses, what may seem like processes of Westernization are often more nuanced. The commercial imperative to create a culturally complete offering requires companies to fully commit to localization for the Iranian market.

Again, Starbucks offers some useful lessons. “Starbucks culture” was born in Seattle, Washington and encompasses everything from the “who the furniture was chosen for, what artwork would be on the walls, what music was going to be played, and how it would be played,” as Hainsworth explains. Starbucks faced an immense challenge in reinterpreting this culture for disparate markets such as China and India. As explained by Revathy Rajasekan in a case study in the IUP Journal of Brand Management, “Starbucks’ entry into tea-drinking India” hinged entirely on a dedicated effort to balance the forces of globalization with the requirements of localization. Despite an aggressive launch, Starbucks’ market entry had stalled until the right culture had been crafted for the Indian consumer. The same will be the case for all multinationals entering Iran.

It may seem incongruous to celebrate establishments like Sam Café and then claim that major corporations seeking to enter Iran ought to use the Starbucks approach to culture. By dint of its success, Starbucks is seen as a bogeyman for the kind of globalization that crushes local proprietors. But in a broadly underserved market like Iran, there is room for both independent businesses and major multinationals. It is worth remembering that Starbucks developed its identity and strategy from its original incarnation as a humble coffee roaster in Seattle. In this way, small businesses, with their inherent connections to local communities and the focused visions of their founders, offer a means to innovate cultural offerings. On the back of Starbucks’ success, which elevated consumer expectations, the “third wave” of independent coffee shops has emerged in the United States and worldwide. A similar sequence is emerging in Iran across cafés, restaurants, retail outlets, and boutique hotels. Often founded by individuals who have proven adept at melding the global and the local in an authentic cultural offering, these new “places” are signaling the larger potential for major multinationals. The revival of the coffeehouses of the past signals the emergence of new consumer expectations in Iran, providing a useful template for any future approach to the promising marketplace.

Photo Credit: Sam Café

The Overlooked Potential of Iran's Women Entrepreneurs

◢ Women suffered disproportionately in Iran's economic downturn. Since 2005, the actual number of women in the workplace has fallen by nearly 1 million.

◢ But the dearth in opportunities has spawned an entrepreneurial streak among many Iranian women.

Recently, President Rouhani halted the third round of public sector hiring that is based on nationwide entrance exams. He instructed his ministers to review the sex-based quotas that have been in place for years. These quotas, which severely restrict womens' access to employment, are not opaque state targets. Rather, they are openly announced on an annual basis. The registration information for the qualifying exams of the education ministry stated upfront that of the 3,703 available positions, only a maximum of 630 will be open to women, regardless of performance on the exam. In larger urban areas where more women may be either merely interested or, more possibly, economically forced to work to make ends meet, there are more restrictive quotas because the pool of male applicants is larger. For instance, when the Ministry of Education needed 190 new hires in Tehran, only six positions were given to women. The field of education is a sector that is female-intensive across countries because teaching is considered as an "appropriate” profession for women since it is conducive for work-home balance.

With even the education sector shutting women out, other sectors are almost impossible for female candidates to penetrate. Thus, women hold only 10% of jobs in the public sector, which is the main employer of the country. During the Ahmadinejad presidency, a set of policies were introduced to presumably support working women to manage their dual roles as mothers and wives. In reality, however, these policies imposed a high cost to employers and created disincentives in the hiring of women. These extra costs were particularly heavy in the private sector, where employers had to bear the expenses. Last year the government announced that since 2005, the actual number of women in the workforce has dropped from 3.96 million to 3.1 million. For any nation, a drop of close to one million workers is a sharp decline. It is especially so for a country with an already low existing base of female workers and a large population. This disproportionality translates into a high economic dependency ratio, i.e. the number of people in a family depending on one earner. Hence, families are increasingly vulnerable to potential economic shocks and policy changes. According to the International Labor Organisation (ILO), the labor force participation of Iranian women is a mere 17%. Iran ranks among the lowest in the world, even below Saudi Arabia– a fact that surprises even Iranians.

There is, therefore, a growing consensus that the female labor force participation has reached alarming lows and that this fact is detrimental to the overall economic and societal health of the country. The issue is now being increasingly debated by economists and policy makers, and not just the women’s rights activists. Another indicator is the urgent emphasis on creating economic opportunities for university educated women. It is for this reason that President Rouhani called for a review of the fairness of quotas. Despite affirmative action quotas for men, and the restriction of certain study streams to female students in some university, women still make up about 60% of university entrants (down from 64% before), solely based on scores in gender blind university entrance exams – the Konkur. Their share in the engineering and science fields--subject matters often dominated by men in Western education systems--is approximately 70%. According to UNESCO, Iran has one of the largest cohorts (in terms of actual numbers rather than just percentages) of female engineering and science students in the world.

Despite the many obstacles, women’s entrepreneurship is a bright light in Iranian society. Market-relevant training, such as engineering and computers, and the dearth in actual opportunities have spawned an entrepreneurial streak in many Iranian women. According to a study by Bahramitash and Salehi, based on a survey of male and female-owned firms that closely follows a similar methodology of the World Bank’s Enterprise Surveys, about 9.6% (applying sample weights) have a female principal owner. Female ownership rises for large firms (50+ employees) to 13.9%. On average, these firms are slightly younger than their male peers (7.1 vs 7.8 years, respectively), which suggests that they are perhaps slightly more technologically advanced than the businesses of their male counterparts. For medium (10-49 workers) and small firms (up to 10 workers) female ownership is 8.2% and 10%, respectively. Bahramitash and Salehi further find that women entrepreneurs are in more dynamic sectors of the economy. Out of necessity, their superior educational accomplishments and ingenuity have resulted in more innovative business models and ventures.

Iranian entrepreneurs have faced substantial obstacles in recent decades. Besides international sanctions, Iranian entrepreneurs must contend with policy uncertainties, limited access to telecoms (especially a slow and constricted Internet), credit constraints, non-competitive behavior in markets, difficulties in obtaining permits, corruption, and the high costs and uncertainties of the legal system. Women entrepreneurs face all of these challenges, and some more. According to the IFC's Women, Business, and Law Report (2016), Iranian women face differential treatment in 23 specific areas of the law. In the Bahramitash/Salehi study, too, women-owned firms (not just the women owners) responded more adversely to sanctions, slow internet, anti-competitive behavior, and policy uncertainty.

On a more positive note, Bahramitash and Salehi found that women-owned enterprises reported fewer problems related to corruption when obtaining permits and easier access to necessities such as finance. This may be consistent with global trends that show that bribe takers are more reluctant to approach women for bribes, and that women have a better repayment track record as borrowers.

Iran is a bastion of opportunities. In the words of Sir Martin Sorrell, CEO of global communications firm WPP, “Iran is one of the world’s last remaining untapped opportunities of that scale, short of Mars and the Moon.” Women entrepreneurs should not be overlooked when foreign companies seek potential local partners. However, most trade delegations visiting Iran have made little effort to engage Iranian businesswomen.Too few foreign delegations have included women from their own countries in their midst. And, male delegations meet Iranian male counterparts, thereby widening the existing gender gap at home and in Iran.

The chief of a recent international delegation that made the effort to meet with a group of women entrepreneurs, commented:

“I can truthfully say that I have never met such a group of dynamic and high ranking women entrepreneurs in one room before. Generally when we have such meetings with the private sector it is with men in the traditional fields and a few token women… so it is quite amazing that Iran has this caliber of women 'marching on.' What was also interesting and possibly counter-intuitive is that when asked if they faced any barriers as women, most of them said they had no real issues in the business arena that related to gender discrimination.”

This is what characterizes true entrepreneurs—seeing opportunities and not the numerous hurdles along the way. In short, Iranian women entrepreneurs are ready, savvy, willing, and able to contribute to the emerging economic possibilities coming to their country. Sidelining them robs everyone of opportunities.

Iran's Business Leaders Must Do More to Protect the Environment

Iran's businesses have a responsibility to protect the environment alongside the government and civil society. Companies should be motivated by both profit and an ethos of corporate social responsibility to adopt more sustainable practices.

In today’s energized, almost-post-sanctions-era Iran, so much has become possible. But as growth takes place, and as increased capital flows into the country, we need to expect more from our business community as contributors to human development.

Businesses are expected to make profits. That is how wealth and jobs are created. That is how lives and livelihoods are transformed. But, along with profits, comes an expectation that the business community must act responsibly in terms of the social, environmental and economic improvement of the communities in which they make these profits. Most notably, businesses must focus on their responsibility to protect our environment.

Facing Grave Challenges

At present, our fragile, endangered planet faces many grave challenges. One of the greatest human development challenges we are witnessing in Iran is the threat of an increasingly hot and dry environment. The environment is being degraded through our actions. Climate change, coupled with the poor environmental decisions of the past, is making Iran hotter and drier. We see a country that is water-stressed, losing its forests, polluted by sand and dust storms, and energy inefficient. We see dramatically less biodiversity than even a decade ago.

The government is trying to reverse environmental degradation, but without the overall level of success required. Due to the scale of the problems and the nature of the causes, these problems can only be successfully addressed when all stakeholders who have had a share in creating them commit to finding solutions.

We all need to start acting sustainably. Governments need to do more. Citizens need to do more. And yes, frankly, the United Nations must also do more. We need to speed up our responses. Fortunately, the governments of the world, including Iran, have agreed to implement the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which came in to effect in January 2016. These goals strive to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure prosperity and peace for all through partnerships. We all need to take the time to learn, understand and apply these goals.

The United Nations is already working closely with the Iranian government to tackle many of the challenges identified through the SDGs. Encouragingly, Iranian authorities, along with most governments worldwide, are starting to frame a response to SDG targets.

Now is the time for the Iranian business community to also become more involved and visible in sustaining our environment. I believe that the business community must get involved both directly and indirectly in order to protect our environment. This can come in two ways. Direct and indirect.

Direct Efforts

Business efforts to reduce the environmental impact will increasingly become a matter of self-interest. Iran has committed, under its draft sixth Five-Year National Development Plan, to implement a low-carbon economy. Given this, plus the global commitments to which Iran has signed up to under the Paris Agreement, the Government will increasingly pass laws and policies which mandate emission reductions. Businesses therefore have a profit incentive to anticipate the regulations which will inevitably be imposed by an Iranian Government increasingly needing to comply with its own international carbon-reduction obligations.

In line with this, businesses should be innovative. Innovation brings about new opportunities and thus benefits the company and the society. “Sustainable innovation” can include such elements as a reduction in water use for production and the encouragement of companies to incentivize their customers to use less water by recycling.

Next, businesses should switch to more cost-effective techniques for their infrastructure. For example, when operating a business, one of the biggest burdens can be the cost of energy. Thus, in order to reduce these costs, the following steps can be taken:

Buy energy-efficient appliances and devices.

Switch off equipment when not in use.

Monitor your corporation’s energy usage by installing the necessary equipment (and act on what the numbers show)

Switch to using renewable sources of energy where possible (such as wind and solar).

But we also need to start with ourselves. And so, another step forward for businesses can be the engagement of employees and customers in sustainable behavior and actions. These actions entail raising awareness about a company's own “sustainable goals,” so that more people can become involved in supporting and helping to achieve those goals. It is the responsibility of every business to send the same message and encourage others to join these efforts.

Indirect Efforts

But there is another – indirect – way in which businesses can act to improve the environment. This is through Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Across the planet, CSR is becoming recognized as a strategic management tool for guiding corporate decisions. The ethos of CSR should also filter down to operations. In the end, and if done well, CSR will powerfully enhance a company’s corporate image in a world where, increasingly, if you are not visible, you are not relevant.

We are no longer in a position to choose pure profit. Our growth must be inclusive. Our development must be sustainable. And our environment must be safeguarded. These ideas were what drove former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan to create the UN’s Global Compact in the year 2000. The Global Compact brings together business, governments, civil society and UN agencies to advance universal principles in the areas of environment, labor, human rights and anti-corruption. This initiative is the world's largest voluntary corporate citizenship pact. At present, over 4,100 companies from over one hundred countries participate. CSR is at the very center of our Global Compact. But there are hardly any Iranian companies represented in the Global Compact. The time has come for this to change.

CSR can contribute to overcoming human development challenges in all countries. Through CSR, companies can financially (or in-kind) support environmental causes and donate to organizations and charities that are working to overcome some of the challenges facing our planet. Irrespective of size, businesses can get involved and send a positive message to others to participate in CSR.

With this in mind, I urge business leaders in Iran to explore CSR and engage in partnerships to make growth more inclusive and more environmentally-sustainable. Living in Iran, I am encouraged by the number of private sector organizations, public corporations, and banks who wish to collaborate with entities – including those like the UN – to promote environmental initiatives and inclusive growth. Although I see encouraging signs within the private sector towards these goals, much more needs to be done.

Today, the world is demanding that companies behave responsibly vis-a-vis the environment. The spirit of “partnership” within the corporate community is at the heart of the SDGs. One goal in particular—Sustainable Development Goal 17—calls on all states to “Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development.” This is a direct call-to-action for the private sector. In order to attain sustainable development we need more hands. Each and every citizen has a role to play.

The UN stands ready to assist Iran's robust business community in promoting CSR.

Photo: Newsweek

New Contracts Offer Synergies Between Players in Iran's Power Industry

◢ Iran's Ministry of Energy has devised Energy Conversion Agreements (ECAs) to encourage investment in power generation

◢ Investment is needed to upgrade an energy grid currently prone to 25% energy loss at peak times

Iran’s power industry is one of the most strategic and advanced industries among the country’s diversified industrial-based economy. The industry is not only strongly positioned to play a crucial role in Iran’s overall economic growth and industrial exports post-sanctions, but it is also a strategic component of the country’s geoeconomical importance in the South Caucuses and Central Asia.

In this new era of possibilities and opportunities, the outlook for the industry’s rapid expansion and economic growth is promising. This expansion is supported by the country’s abundant fossil fuel resources, over 600 different equipment-manufacturing companies and contractors, and over four million specialized technicians with electrical engineering backgrounds. Additionally, Iran’s large reserves of copper, aluminum, zinc, polymer, and other major raw materials allow robust capabilities for the domestic manufacturing of turbines and electrical components.

Nevertheless, considerable inefficiencies affect all segments of Iran’s power industry value chain. These deficiencies will continue to create challenges for the sustainable development of the sector. While foreign investment, and its hype, have become the main focus for meeting development objectives, other critical factors should be taken into account as the country makes its way back to the global arena.

Investment Incentives and Barriers

To attract new sources of capital to efficiently and quickly develop the power sector (for which the utilization of Class F and H turbines with net efficiency levels of 56% and 61% respectively are required), the Ministry of Energy (MoE) has introduced Energy Conversion Agreement models (ECAs) within Build-Own-Operate (BOO) and Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) frameworks. In an attempt to reduce bureaucracy and increase efficiency in the processing of investment applications, MoE established Iran’s Thermal Power Plants Holding Company (TPPH) in early 2016, assigning it with the overall responsibility of negotiating investment deals and issuing required permits and licenses.

The Iranian power ECAs are based on two major principles: 1) free feedstock gas supply and 2) guaranteed electricity off-take at competitive tariffs. Both of these components are offered over five-year periods. The MoE has reached an agreement with the Ministry of Petroleum for the supply of gas which is converted to electricity for consumption in domestic markets. As such, these agreements are considered Energy Conversion Agreements as opposed to conventional Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) offered elsewhere. The gas supply agreement has not been immune from political clashes between the two ministries, however. Officials of the Oil Ministry contend that by giving the project owners the opportunity to export electricity, the free supply of gas to power plants could undermine Iran’s gas export capabilities when the ECA’s term comes to an end.

ECA Model

- Fixed 5-year agreement with free supply of feedstock gas

- Guaranteed off-take agreement at pre-determined prices (which will be adjusted annually to protect investors against inflation and exchange rate fluctuations)

- Guaranteed (almost) free access to the grid for 20 years

- TPPH fixed financial modeling offering a 20% IRR

- After period of five years, the power plant can trade its electricity at the Energy Exchange market, or sell it to national or international off-takers at market prices

In order to ensure investor confidence, Iran’s Ministry of Economy and Finance backs the ECA agreements with a sovereign guarantee for the FIPPA-registered equity capital and incurred interest, which in turn, facilitates the means for investors to acquire finance at a low interest rate from international banks. In light of these attractive terms—often described as “too good to be true”—many international power companies, particularly those from Germany, Turkey and South Korea, have already signed MOU's with TTPH for multi-thousand megawatt power projects across the country.

While the MoE has been successful in attracting foreign investment, it has been less successful in engaging the Iranian private sector—namely manufacturers and contractors active in electric engineering, consultancy, and power plant construction. The post-sanctions policy of creating a "resistance economy", endorsed by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei, puts a great emphasis on the importance of empowering and supporting Iranian companies in their post-sanctions reintegration into the international economy. Entities that worked diligently and successfully during the era of sanctions to ensure the generation and flow of electricity are specifically rewarded. The requirement for establishing partnerships with competent Iranian companies – a requirement also included in the Iranian Petroleum Contracts (IPCs) - should be incorporated in power sector development contracts as well.

Another major development barrier in Iran’s power market is that despite a massive installed capacity of 75,000MW, a large number of power plants operate using extremely inefficient single-cycle E-class turbines with a stagnant efficiency of 30-35%. This level of inefficiency is even higher when combined with the energy loss in the transmission and distribution systems caused by old, inefficient and depleted network utilities and technologies. Half of the electricity appliances and cables in the distribution system are over a quarter-century old and cannot withstand heavy loads during peak times. According to a report published by the Parliament Research Centre in July, 2015, the actual level of power loss in Iran’s power system (energy conversion and transmission and distribution networks), ranges between 19-22%, and increases to over 25% during summer peak times. In practice, this means that for every 1000 MWh electricity generated during the peak time, a staggering 250MWh is wasted.

Heavy state subsidies and underpriced natural gas supplied to power plants result in depleted efficiency in Iran's power grid. A low tariff structure has caused a trend of excessive and inefficient consumption pattern per capita and the resulting inability to recover costs has led the industry to accumulate significant debt. The situation has been recently exacerbated by the urgent requirement for capital investment in developing new capacities to meet an unprecedented growth in demand. This requirement is expected to increase even further in light of post-sanctions economic growth. The expanding structural deficit has been a daunting burden on both the government and the private sector. A yearly investment of USD $5-6 billion has been required to meet the annual growth demand of 6% (or 5000 MW).

Iran as a Regional Energy Transit Hub

Iran’s power industry could play a critical role in enabling Iran to become a major regional electricity-dispatching hub, connecting the Caucuses and Central Asia with the Middle East. In addition to the realization of this project, the development of the larger alliance of the North-South corridor, which is being created among Russia, Azerbaijan and Iran, also has a strategic value for Iran. Unlike gas exports, which always face political barriers and fluctuations, electricity exports portend not only revenue, but also Iran's geo-economic relevance by creating economic and energy interdependency.

One of the major geopolitical objectives of the Iranian government is to ensure its regional ambitions by promoting energy diplomacy. While substantial progress has been made to date, (such as the synchronization of Iran's extensive national grid with all of its immediate neighbors, including Turkey, Iraq, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan), this corridor requires substantial cross-border infrastructure development. The Iranian power industry, with the help of the private sector, should be at the forefront of this development. By allowing investors to solicit customers both domestically and regionally, these projects would also provide an attractive opportunity for investors to tap into regional markets for export of their generated electricity once their five-year power purchase agreement comes to an end. The ever-growing electricity demands of the Emirates, Oman and Kuwait offer a unique opportunity for power project developers in Iran.

The market knowledge and engineering know-how of Iranian companies, combined with the technological capabilities of foreign companies, will result in lucrative and substantial endeavors. As Iran re-engages with international markets, the most important policy for both government officials and Iranian power sector players is to grow sustainably, with a view to the long-term interests of the country.

Photo Credit: GE

4 Megatrends That Support Rising Tech Entrepreneurship in Iran

◢ Entrepreneurial change starts with the individual, but is buoyed by favorable trends

◢ Megatrends in demographics, economics, communications technology and capital are driving growth in Iran's tech sector

Before talking about the key megatrends supporting technology entrepreneurship in Iran, I'd like to introduce the “change formula:"

(V x D) + FS > R = C

In this formula, C = change; R = resistance (fear of change); V = vision (a picture of what future looks like); D = dissatisfaction (pain of being on a burning platform); and FS = first steps (courage to take the first steps).

The change formula shows us that change needs to come from within. But at the same time, entrepreneurs look to favorable trends which help change happen faster and more readily. To analyze key "megatrends" in Iran we at Iratel Ventures used modified versions of the National Innovative Capacity and National Innovation System frameworks. Each topic forms the basis of our continuous and improving research.

The 4 key trends shaping entrepreneurship capacity in Iran are:

- Demographics (Culture, Education, Employment)

- Economics (Reconstruction, Reformation, Innovation)

- Communication Technology (Fixed, Mobile, Internet, Unified)

- Capital (Flight, Infrastructure, Exploratory, Venture)

Of particular interest to us is how venture capital will scale tech entrepreneurship among Iranians. An important aspect of this consideration is that pure scientific and technological advances which do not lead to economic applications are not a sustainable option for venture capital.

1. Demographics (Culture, Education, Employment)

Firms in innovative countries are willing to invest heavily in R&D, and have moved beyond extensive use of technology licensing. Companies focus on building their own brands, controlling international distribution, and selling globally, all of which are complementary to innovation-based strategies. Organizationally, firms from innovator countries engage in extensive training of employees, delegate authority down the organization, and make greater use of incentive compensation.

This is the vision for the future. This is the culture we need to establish in Iranian companies. One that is universal and capable of attracting top talent, not just domestically but internationally.

Having said that, Iran has abundant potential talent with 60% of the youth under the age of 30. This represents an amazing workforce but also a challenge. We need to create 1m jobs annually to keep employment under control but are only generating 300k.

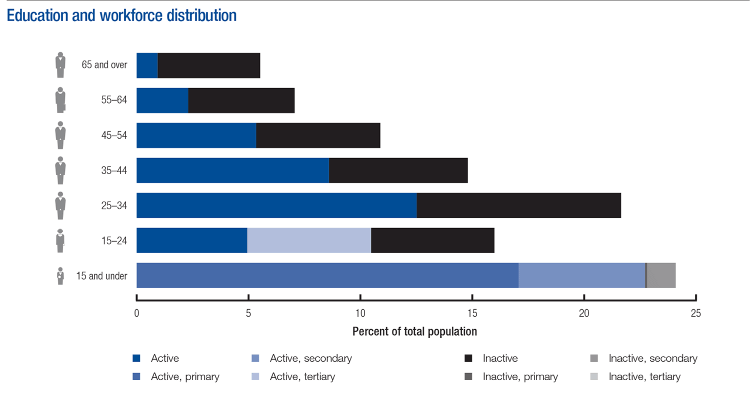

Source: World Economic Forum

This pool of talent is highly educated. According to the World Economic Forum, Iran has the third highest number of graduates in engineering, manufacturing and construction (in absolute and per capita numbers).

If they’re not provided the opportunity to work on what they’re good at, Iranians will seek opportunities overseas. This phenomenon of "brain drain" is exactly what happened during the last two decades. The good news is that many are ready to establish businesses here (if not already) and make a real contribution.

This is the result of many years of good work in education, culture building and wanting to improve our place in the world. We are at the crossroads. We need to use these gifts properly or risk losing the opportunity. These high levels of innovative assets (scientists, engineers, and to some extent research institutions) have so far been hampered by the business environment and the competitive landscape in our country and now is the time to change.

2. Economic (Reconstruction, Reformation, Innovation)

Many policy discussions assume the existence of a sharp tradeoff between goals such as health, environment, safety, and short-term economic growth. However, a healthy rate of innovation increases the likelihood that new technologies will emerge that substantially temper or even eliminate such tradeoffs.

One of the main characteristics of the post-revolution economy in Iran is that growth at any rate may not be the top priority. The macro environment is affected by how economic decisions are made and how different parts of the economy are optimized in light of factors beyond profit.

This coupled with the economic shock due to the revolution, put industrial R&D and innovation at the bottom of the economic agenda. The restructuring of universities and the subsequent war led to further widening of the gap between R&D and industry. The international sanctions and eight years of devastating war further eroded our economic powers and pushed the country to the brink of economic collapse where real per capita income dropped 61% from the high of 1976 to the low of 1988.

The post war period presented an opportunity for ambitious rebuilding. Although there were great advances in this period and infrastructure was the primary beneficiary, there was still a lot of debate hampering growth. Most of the activity came from the public capital, however, private capital was slowly gaining confidence.

During the reformation, we had many social and cultural initiatives, but little in the way of economic reforms. The country was facing internal as well as external pressures especially with record low oil revenues. A bright spot was that private financial institutions and banks were set up and the first steps in turning private capital into a real player were being taken.

Next came a period of further shocks and economic isolation marked by inward looking policies that focused on tax and subsidies, rather than growth. With little incentives to stay and international pressures, foreign investors left. However, private capital was booming in many consumer related industries and there was a big disconnect between public and private economies putting further social pressure on the country. The spring was being compressed even further.

In the new post-sanctions phase, the economy is at the top of an agenda marked by an outward looking vision to reconnect with global trade and to emphasize “knowledge based” companies. One can only hope for a bright future where economic policy will act as a tail-wind for innovation.

3. Communication Technology (Fixed, Mobile, Internet, Unified)

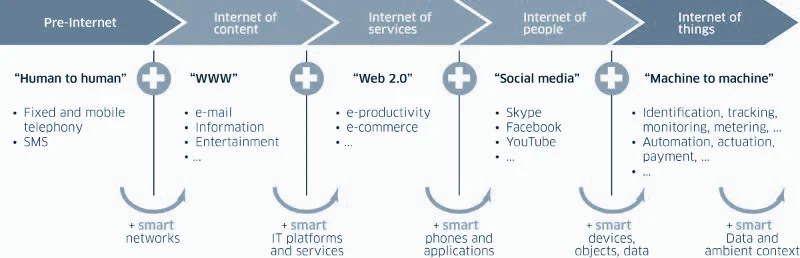

Communication technology has had a tremendous effect of shifting an inward looking local innovation to an outward global one.

In parallel with everything that was going on in our country, the world was entering the information age at great speeds, embracing a global many-to-many communication platform called the internet.

With the convergence and unification of voice, video and all other types of communication using smartphones, the possibilities of building bigger, more open and more useful services are multiplied by an order of magnitude. Given the right circumstances, these technologies will connect us to a global audience at the push of a command and make building of previously unimaginable businesses possible. Imagine you’d told someone 40 years ago that they’ll be able to communicate with 5m people simultaneously and get responses from them in real time!

Iran was no exception in adapting this tremendous communication technology. Iran was an early adopter of the GSM standard resulting in a jump to the digital world. By the late 90s, Iran was the largest country in the ME in terms of mobile phone volumes and by mid 2010s, Iran had he highest internet population and the second highest number of smartphones in the region.

The internet and communication evolution is only marching on, with an ever increasing number of things coming online, we will have a unified system gathering, analyzing, optimizing and automating many things we do in our daily lives.

4. Capital (Flight, Infrastructure, Exploratory, Venture)

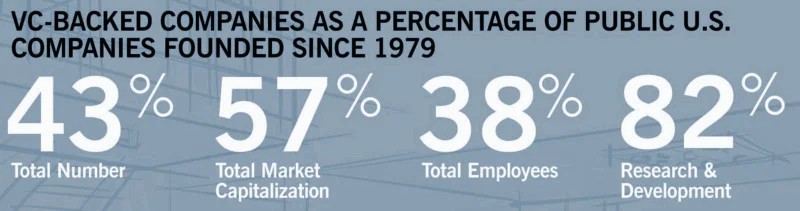

The availability of venture capital reflects the importance of risk capital in translating basic research into commercializable innovation.

Venture Capital is considered as the main financial driver of entrepreneurship that can ignite innovative streams due to its high risk tolerance and expectation factor.

In the years before the revolution and the first 10 years following the revolution, the country saw huge capital outflows and frozen assets due to political issues. During the infrastructure building phase, capital, mostly public, was being allocated to rebuilding efforts. Infrastructure investments in the major industries as well as newer ones (e.g. telecoms) was picking up. At the same time, the country’s private capital was still far from having any influence. Private capital had limited access to opportunity and was primarily locked in real estate and trade.

However, a period of economic reform began to unlock the potential in local industries. Privatization gathered pace and private financial institutions were set up and private capital started feeling more opportunistic. This helped shape the nucleus of the private capital which would take at least a decade to grow and become an important player. During the later reformation years, capital started exploring adjacent and relevant markets outside Iran. However, with the new rounds of sanctions this exploratory phase came to an abrupt halt and returns were diminished.

This growth opened the way for the emergence of a new trend, the rise of venture capital. Venture capital knows that the only way to build meaningful and sustainable returns is by building products and services that will go beyond the local constraints and have the potential to have a global footprint. Both public and private capital moved towards venture applications. Public capital was becoming more structured as seen in the establishment of a Sovereign Wealth Fund in Iran with local as well as global aspirations. Private capital had long been stuck in bank deposits. But lowered interest rates have begun to influence depositors to seek our investments that can contribute to economic production.

Source: Stanford Business School

It is this kind of capital that can move fast, add value on an operational level and bring new ways of connecting with a global audience. This is the only way we can build an innovative platform for global Iranians. Once capital gets moving, its momentum will impact the other trends and positively compound their progress.

As direct beneficiaries of many (if not all) of these trends, it is our duty to be the change we want to see in our community. This is why we think that supporting entrepreneurship is the biggest contribution we can currently make. It allows us to take a long term view and patiently build a strong foundation towards an innovation driven economy for a more prosperous Iran.

Banner Photo: World Economic Forum

Seeing FDI as Iran’s Biggest Communications Challenge

◢ Attracting FDI is highly competitive, and Iran needs to improve its attractiveness as an investment destination.

◢ Iranian businesses need to understand both hard and soft drivers of perception and craft strategies to get hesitating investors engaged.

So much has been said about the outstanding opportunity that Iran presents for investors around the world. The country has been described as the last great emerging market opportunity available to global investors. Throughout the prolonged period of international negotiations that led to the JCPOA, the headlines focused on the significant economic fundamentals of the country—a population of 80 million people, a highly educated and skilled workforce, huge natural resources, and relatively sophisticated banking and legal systems, just to mention a few. Iran should be an enticing prospect for international investors operating in a low-growth global environment. Much has also been said about the need for Iran to attract the necessary FDI, technology, and expertise to re-invigorate an economy that has been left behind during a long period of international sanctions. But there has been less focus on the specific challenges Iran faces now as it promotes itself for greater engagement by foreign companies and investors--notably the difficult job it has to improve perceptions about the country as an investment destination.

Attracting FDI is Highly Competitive

Attracting serious FDI to a country is a highly competitive business, as so many emerging economies and developing countries now vie with one another to position themselves for investment. For Iran, isolated for so many years under sanctions, the process of promoting itself for foreign investment is going to be a major task as it seeks to compete with every other emerging market economy in the world – many of whom have become adept at global marketing and commercial diplomacy. Before launching a global advertising and media relations strategy, however, those in Iran mandated to promote FDI will need to understand what factors influence FDI decision makers. What drives a global corporation or a financial institution to invest in a country that has potential for growth, but presents significant risks?

The Drivers of FDI Decision Making

The business of attracting FDI to a country is atwo-part "contact sport". Firstly, it requires a strategic approach to understanding how investors behave when considering a destination for FDI. Secondly, there must be government-level commitment to engage closely with those investment decision-makers and stakeholders as they start to shape their sentiments around a specific investment opportunity. This requires an adequately-funded and serious communications strategy and engagement program at a national level.

In many years of working with countries and sovereign entities on FDI communications, I have learnt that a number of universal factors drive investment decisions. They can be referred to as the "hard" and "soft" drivers of investment.

Hard Drivers of Investment

The hard investment drivers influencing corporate decision makers as they consider whether to invest in a new market are principally economic. The first questions that need to be answered include what are the scope and nature of the potential business and what is the specific opportunity in our sector? It is therefore highly important that potential investors have this information available to them. For a country like Iran, isolated for so long and not used to making information available to international audiences, this will be a challenge. I find that there is a dearth of good economic information readily available on the country for international audiences. This void will need to be addressed by both trade groups and the government, in due course. Current levels of awareness about the specific investment opportunities in Iran are staggeringly low. In the UK, for example, many people compare Iran to its neighbors such as Afghanistan or Pakistan, rather than to Turkey, a more analogous comparison. This fact reveals the state of current investor misperception and ignorance regarding the country. When combined with the negative media coverage the country tends to receive from both the global and US-centric business media, a strongly negative view is created. The case for investment in Iran is a difficult one to make in the boardrooms of Europe because the perception of risk is combined with a low level of awareness of the actual economic opportunity and business environment.

Other hard drivers focus on the standard accepted processes of due diligence needed when considering a new market. Key questions that need to be addressed in FDI communications are: What are the corporate governance standards? Is the legal system reliable? What are the levels of transparency? What are the levels of corruption? How pro-business is the government? Again, the country needs to be seriously proactive in dealing with each of these issues and addressing justifiable concerns. Global indices play an increasinglyvital role in shaping investor decisions. As Iran ranks markedly behind its regional neighbours in key areas, the country will need to decide how to engage with indices such as the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom (Iran ranked 171 in 2016), World Bank Group’s Doing Business Report (Iran ranked 118 in 2016), Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (Iran ranked 130 in 2015) and World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report (Iran ranked 74 in 2015-16).

While these global rankings reflect Iran’s lack of engagement with the teams who compile them, they will collectively create a powerfully negative picture as investment decision makers assess potential opportunities in Iran.

Soft Drivers of Investment

The soft drivers of investment are centered around culture, not hard economic data or global rankings. Interestingly, soft drivers have a huge influence on FDI decision making. Therefore, government FDI communication has to shape both cultural and investment perceptions. Questions to be addressed include: Are women able to occupy senior roles in business? What are the career opportunities for women in the country? How strong is the infrastructure? Are there decent hotels and transport and flight links? Will my senior staff want to be posted to the country? In short, what is the "likeability" factor of the country? It is imperative that the country’s investment communication addresses these softer considerations. Because Iran has a positive narrative to highlight in this area, it must devote significant resources to building an effective campaign to addresses both hard and soft drivers. After all, decision makers are more likely to invest in a country they like.

Perception Research

The first step in developing the FDI communications program will be to conduct perception research in key markets and sectors. Perception research should be qualitative, and include in-depth interviews with investors, compliance managers, and regulatory bodies in key markets. This is a key tool in establishing a true picture of how the country is perceived by potential investors and target companies. Only then can an effective communications strategy and engagement program be developed and launched to change perceptions.

A year after the signing of the JCPOA, there is much frustration both in Iran and in Europe about the slow pace of the resumption of trade and international banking with Iran. Interested international investors are unlikely to commit to major investments until convinced that Iran is open for business. During this lull, those charged with promoting FDI into Iran must work diligently to shape perceptions and build investor appetite.

Photo Credit: SAIPA

How Think Tanks Influence the Debate on Iran

◢ Think tanks played a crucial role in both sides of the debate surrounding the Iran Deal.

◢ The success of the Iran Deal continues to depend on the influence of think tanks, particularly in Washington D.C.

At the 3rd Iran Europe Forum in Zurich earlier this year, Iranian business leaders attending frequently asked: What is a think tank?

The concept of the think tank originated in the United States with independent research institutes such as the Brookings Institution, which was founded in 1916 by a St. Louis businessman named Robert Brookings. Brookings established the institute with the goal of providing research in the fields of foreign policy, economics, and development. The actual term “think tank” was first applied in 1959 to the Center for Behavioral Sciences in Palo Alto, California. The term has since become a catch-all for thousands of organizations around the globe with a variety of agendas, funding streams and output. In some countries, think tanks are offshoots of the government and are managed by officials. The Institute for Political and International Studies in Tehran, which is affiliated with the Iranian Foreign Ministry, is one such example.

In the United States, most think tanks are privately funded by foundations and individuals, and seek to influence U.S. policymakers by publishing reports, testifying on Capitol Hill, and holding public and private events. The State Department’s Policy Planning Staff lists about 60 think tanks, mostly in Washington but some abroad, that it finds “particularly useful” in helping the department shape U.S. foreign policy.

Many U.S. think tanks, including the Atlantic Council, the Brookings Institution and the Center for Strategic and International Studies, are bi-partisan and do not endorse political candidates. They strive for balance in their staffing, analyses and events. However, their scholars are not barred from taking positions on contentious issues and are encouraged to put forward their ideas. Other organizations, such as the Heritage Foundation and the Center for American Progress, have clear leanings to the right or to the left of the political spectrum. These entities often act as lobby groups.

During the heated debate that took place last summer in Washington over the Iran nuclear deal, a number of think tanks and other organizations sought to influence the outcome. Many of the groups in support of the deal received small grants from the Ploughshares Fund, a non-profit based in San Francisco that seeks the elimination of nuclear weapons. Ploughshares was praised in the Journal of Philanthropy for its “creative and nimble thinking” in coordinating the successful campaign in support of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Among the groups that received funding from Ploughshares for their work on Iran were the Atlantic Council, the Arms Control Association, the Friends Committee on National Legislation (a lobby connected with the Quakers), and J-Street (a liberal Jewish-American group).

Groups on the conservative side of the political spectrum were much better funded. These organizations included the neo-conservative Foundation for Defense of Democracies and the powerful pro-Israeli government lobby, the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC). In total, they spent an estimated $40 million on anti-JCPOA advertising directed at the U.S. Congress-- a staggeringly larger sum than that spent by the pro-deal camp. In the end, however, the effort failed to convince a sufficient number of Democrats that there was a better available alternative to the JCPOA. Indeed, the JCPOA never even came up for a vote in the U.S. Senate because opponents could not muster the 60 votes required to end the debate.

The Atlantic Council, which was founded in 1961 to promote U.S. ties with Europe, did not take a position on the JCPOA. However, a bipartisan Iran Task Force organized in February, 2010 under the leadership of then-Atlantic Council chairman (and later Defense Secretary) Chuck Hagel and former Ambassador to the European Union Stuart Eizenstat, did issue a statement in July, 2015. It gave qualified endorsement to the JCPOA while urging “special vigilance against any violation of its terms.” The Task Force also organized two private, bipartisan dinners in Washington in August, 2015 with Energy Secretary Ernie Moniz, a key member of the U.S. negotiating team. Similar events were held in New York in the fall with the Iranian ambassador to the United Nations, Gholamali Khoshroo, and with Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif.

The Task Force, which has since evolved into a broader Future of Iran Initiative, seeks to increase the JCPOA’s chances for success and build on its model for conflict resolution. The Initiative also tries to promote a deeper understanding of Iran through reports and panel discussions such as a recent symposium on the implementation of the JCPOA that was addressed by two key administration officials – Deputy National Security adviser Ben Rhodes and John Smith, the acting head of the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control(OFAC).

In large part because the U.S. and Iran have lacked formal diplomatic relations since 1980, there is a dearth of expertise and knowledge about Iran in Washington foreign policy circles. Members of Congress, in particular, tend to view Iran through the lens of official Iranian anti-American and anti-Israel rhetoric. At the Atlantic Council, we strive to show Americans a more nuanced and realistic perspective on Iran by sponsoring events that feature individuals who have had first-hand, recent experience in Iran and who can speak to all aspects of the Islamic Republic.

Among the events the Initiative has held this year were a discussion on sports diplomacy, showcasing visits to Iran by U.S. wrestlers, a panel on hi tech startups and the innovation economy in Iran, and a discussion on the ramifications of the Iran-Saudi rift on regional conflicts. The Initiative also put out a balanced report on Iran’s human rights policies and organized a discussion that included experts on other countries in the region, including Saudi Arabia. The Initiative has also hosted Iranian officials, including Valiollah Seif, the governor of the Central Bank of Iran, for private discussions about the Iranian economy and the impact of the JCPOA. For the remainder of this year, the Initiative is planning events on environmental challenges in Iran’s Hamoun wetlands, the experiences of U.S. Peace Corps volunteers in Iran, and the country’s contemporary art scene. The Initiative also publishes a blog, IranInsight, with articles in both English and Farsi.

While there are other think tanks in Washington that have held events on the nuclear deal or Iran’s regional role, the Initiative is unique in its wide-angle view of the country. We feel we are performing an important service by acting as a bridge between two cultures that have been divided for far too long.

Photo Credit: Atlantic Council

Why Hotel Development in Iran Has Investors Excited

◢ Iran is expected to welcome 20 million tourists per year by 2025, but the country currently boasts just 650 hotels.

◢ International brands are moving into the country and strong market potential means that investors can find favorable incentives and financing packages to support development.

The lifting of sanctions on Iran has opened range of investment opportunities in the hospitality sector. After more than 35 years of economic isolation, Iran has a strong need for investments in hospitality infrastructure and will provide a major opportunity in next few years.

Iran is an extremely attractive tourist destination. The country has a rich cultural heritage with 19 UNESCO listed sites. Its tourist attractions range from ancient Persian ruins to beaches on the Persian Gulf and Caspian Sea to ski resorts in the Alborz mountains.

According to the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC), Iran’s tourism industry contributed 6.1% of the country’s GDP in 2014. This proportion is expected to rise by an average annual growth rate of 5.5% through 2025. Visitors export generated IRR 24,903.4bn (1.1% of total exports) in 2014 and is forecasted to grow by 3.0% pa to IRR 34,604.1bn in 2025 (0.8% of total). Moreover, WTTC data shows that the country hosted around 5 million tourists in 2014. Taking into account the positive effect of lifting of economic sanctions on Iran, this flow of tourists is expected to increase steadily to reach 20 million by 2025.

Considering its young population, 60% of which is below the age of 30, relatively high GDP per capita, and a location Iran has a strong potential to become a leading tourism market globally.

Before the 1979 revolution, Tehran’s hotel market had one of the highest penetrations of international hotel operators in the region with IHG, Hyatt, Hilton and Starwood operating hotels in prime locations. Following the revolution, the industry witnessed decades of stagnation. The departure of international hotel operators had significant impact on the quality of hotel management, resulting in a generally low quality of service.

Since the lifting of sanctions, Iran’s government has demonstrated that it is eager to attract foreign investment to meet rising demand. In the last year, the number of business travelers in Iran has increased significantly, creating demand for branded hotels operated by international hotel chains. Acording to research by Horwath HTL, a global hospitality industry consultancy, Iran currently boasts just 640 hotels with 96 located in Tehran, of which only 2 belong to an international brand. In comparison, Istanbul alone has 57 branded hotels.