Fortune Telling: JCPOA and a New Year for Iranian Bankers

◢ The new year holiday has Iranians hoping for a brighter future and more prosperous household.

◢ At the same time, the nuclear negotiations underway in Lausanne are the source of great hope, but also trepidation for Iran's bankers.

On April 2, Iranians headed for nature on the 13th day of Farvardin in the Iranian new year, a day called sizdah be-dar. While spending time with family and conducting little ceremonies to bring good fortune, many Iranians contemplated the ongoing nuclear negotiations in Lausanne, Switzerland. The course of the new year seemed to hang in the balance as the negotiations stretched past their original deadlines.

Finally, late at night, Iranians received the best news in a decade, akin to some to the collapse of the Berlin Wall. Iran had reached a framework agreement with the six world powers of the P5+1. The agreement provided assurances for the exclusively peaceful nature of Iran’s nuclear activities, and heralded the lifting of all nuclear-related economic sanctions. The deal seemed to mark a new era of economic opportunity for all 80 million Iranians.

Perhaps no one was more relieved than the Governor of the Central Bank of Iran (CBI), Valiollah Seif, whose organization stands to gain so much through the implementation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) announced in the joint statement made by Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif and EU foreign policy High Representative Federica Mogherini.

CBI has suffered tremendously since the intensification of financial sanctions in 2012 and the expulsion of Iranian banks from the SWIFT global interbank messaging network. CBI reportedly has between $80-100 billion dollars frozen in accounts overseas, inaccessible due to the sanctions.

Iran's commercial lenders have also been victims of the financial sanctions leveled against them by the European Union and the United States. They are cut off from their overseas businesses and transactions with their foreign counterparts, leading to crises of liquidity and leveraging.

European banks can also find cause for relief, having been hammered for failure to comply with the myriad sanctions regulations. Firms such as BNP Paribas and Commerzbank have had a rough time with US authorities, forced to pay billion dollar settlements to the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC). A rollback of financial sanctions will reduce the legal risk of Iran trade, and eventually these banks can carefully revive their business with Iranian banks and even enter Iran's financial markets directly.

Overall, the prospect of sanctions relief offered by the JCPOA led usually reserved bankers and investors to shout for joy.

High Hopes and a Long Road

The talks between Iran and the P5+1 - Britain, France, Germany, China, Russia and the United States - blew past a self-imposed March 31 deadline with no certainty that they would not end in failure. Yet, after eight days of marathon talks, the JCPOA was announced to much fanfare. The negotiators have until June 30 to work out the details for implantation of the final deal.

But there is a long road ahead. Diplomats close to the talks say the deal is fragile. The understandings reached on April 2 could collapse before June 30 and experts believe it will be much harder to reach a final deal than it was to agree the framework accord. Even if a final deal is reached, factoring implementation, there is still a long way to the lifting of sanctions. Therefore, the sanctions, compliance investigatons, and the general isolation faced by Iranian firms will remain in place for the coming year. As Iran’s Foreign Minister Zarif succinctly put it, "We're still some time away from reaching where we want to be.”

Based on statements made by official on both sides of the aisle, and a fact sheet released by Washington, the JCPOA contains a pathway for the removal of all nuclear related sanctions as the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) verifies Iran’s commitments. Under the JCPOA terms, Iran will receive gradual relief from US and European Union nuclear sanctions as it complies with steps to eliminate or convert its nuclear facilities and increase the so-called “breakout time” that would be necessary to produce a weapons-grade nuclear material.

These terms allowed Zarif and his team to claim victory on the promise of sanctions relief by the P5+1. But as the negotiators of each country began the tough task of selling the deal to domestic constituencies, divergences emerged about exactly how gradual sanctions relief would be.

The simple fact is that implementation will take time, so CBI will need to navigate the new Iranian year of 1394 much the same way it weathered the last. It will enjoy only limited access to its foreign reserves, and continue to operate under general isolation.

Change in the Winds

Despite the sobering challenges of implementation, the JCPOA does allow Seif and the CBI bankers to think about the normalization of financial relations with the world. The positive psychological effect of the deal on Iran's foreign exchange market will definitely help the bank unify the foreign exchange regime– an elusive aim pursued by the CBI for over a year.

Notably, while the unification of the exchange rate system is a key priority, in the near term, Seif has signaled that CBI will allow the “appropriate currency rate set itself according to economic conditions.” The implication is that an improved mood among investors and business leaders will strengthen the wider economy to the point where CBI could pursue monetary policy more confidently. Already, the investment climate has improved. The Tehran Stock Exchange (TSE) saw big gains in response to the nuclear negotiations, with the rial making smaller advances against the dollar.

Of course, the removal of sanctions, coupled with the Rouhani administrations' cues about opening the market, means the prospect of increased foreign investment. All branches of the financial services industry stand to gain from this, including retail and commercial banking, asset management, investment banking, etc.

There are untold opportunities for bankers in the midst of the normalization process, even one as protracted as the JCPOA might entail. Many are getting ready for the battle that’s about to begin over market share in Iran's financial sector. For now, it seems Iran's misfortunes are coming to a (slow) end and the news could not have come on a more providential date than the 13th day of Farvardin.

Photo Credit: Guardian

Bringing FDI to Iran: 3 Key Tactics of Business Diplomacy

◢ Ensuring a potential nuclear deal remains a robust and lasting agreement will require commitments from stakeholders beyond the currently engaged diplomats.

◢ The business community in Iran and the West can play an important role in “stewarding” a nuclear deal.

Back in November, as the nuclear negotiations between Iran and the P5+1 nations seemed headed for an agreement only to result in a second extension, I wrote a piece about how the business community in Iran and abroad will need to “steward” a deal after it is signed.

Now that a preliminary agreement seems just moments away, laying the groundwork for a full agreement to be defined by June 30th, it may be time to revisit the notion of stewarding a deal.

My fascination with the question arises from a simple assessment; the deal is not an end in itself, it is merely a means to a whole range of activities that have been long overdue for Iranian businesses and the economy they serve.

The development of Iran’s economy since the Islamic Revolution in 1979 has been defined by attempts at self-sufficiency—a quality seen among most governments that have tried to cobble together a state in the aftermath of revolution.

In the pursuit of self-sufficiency, a wide range of government programs or initiatives came into effect. These included social policies, such as the expansion of the educational system across primary, secondary, and tertiary education, which boosted literacy rates nationally and the overall competitiveness of Iran’s workforce. It also included industrial policies, such as the development of domestic manufacturing capacity through import substitution industrialization.

The total consequence of these policies— though they were never instituted perfectly—has been to position Iran as a country with decent capabilities across nearly all the key factors that impact economic growth.

However, one key element has been largely missing. As a result of international sanctions and a persistently negative political climate, Iran has remained disadvantaged in its attempts to secure foreign direct investment (FDI). When compared with its regional neighbors, Iran has been left behind.

Over the last 10 years, Iran’s annual FDI inflows, measured as a percentage of GDP, have had half the magnitude of inflows in Turkey, and a third of the magnitude of inflows in the United Arab Emirates. In 2009, Iran’s FDI as percentage of GDP was a staggeringly just one-tenth of the levels seen in Qatar and Saudi Arabia.

Foreign direct investment, net inflows (% of GDP)

Although many reports have noted an uptick in trade relations with countries like China, India, and Brazil in an a response to sanctions, there has not been a marked improvement in FDI inflows over the last 10 years.

The stagnant figures are particularly surprising when one considers that Iran’s economy is perhaps the most diverse, mature, and demand-driven economy in the region, even surpassing Turkey in some key metrics.

Without an influx of foreign capital and the related impact on economic growth, Iran will remain unable to realize its economic potential. In this regard, a nuclear agreement will have two important impacts for the future of FDI in Iran. First, it will enable policymakers to begin the hard work of road-mapping and then enacting sanctions rollback. Second, it will markedly improve the political position of Iran in the international community, reducing the perception of the country as a rogue state or pariah.

However, both of these impacts are essentially superficial—they will not necessarily increase levels of FDI. Rather, in a post-deal scenario, Iranian businesses will have the new opportunity to pursue investments or partnership arrangements with foreign firms in a more concerted fashion.

The emphasis here is on being active. Because of the particularly longstanding isolation of Iran from international markets for goods, services, and capital, Iranian businesses cannot afford to remain passive and assume that opportunities will land on their doorstep.

Therefore, “stewarding” the deal means making the necessary strategic, operational, and tactical decisions for business development in order to capitalize on the initial improvement in the sanctions and political landscape. If Iranian businesses, working together with foreign firms, can create success stories on the ground—it will become significantly more likely that a the deal will become the basis of a larger détente.

So what are the key strategies, operations, and tactics to bring to bear? First and foremost, stewarding a deal means engaging in “business diplomacy.”

As I described in my November piece, “business diplomacy can be defined as the establishing and sustaining of positive relationships (by top executives or their representatives) with government representatives and non-governmental stakeholders with the aim of building legitimacy (safeguarding corporate image and reputation) in a difficult business environment.” This definition is taken from the excellent scholarship of Professors Raymond Saner, Lichia Yiu, and Mikael Sondergaard, who developed the concept of business diplomacy about 15 years ago.

If the strategy for Iranian businesses is to seek increased degrees of foreign investment and engagement, then business diplomacy will be a key operation. Subsequently, team members in the organization need to be able to deploy three main tactics as part of business diplomacy operations: brokerage, diffusion, and collection action.

The goal of brokerage is to enable Iranian businesses to earn a place at the negotiating table, whether that means earning access to high-level meetings with potential partners and investors, or participating in industry events overseas. Brokerage entails linking the currently unconnected groups or entities (Iranian businesses and international firms) by finding shared challenges and common ground. These linkages should extend both within and without the private sector—meaning that relations with government agencies, industry bodies, and watch groups overseas will also be important for Iranian firms. Executives will need to develop new skills to handle these relationships.

Once links are formed, the next tactic is diffusion, which is about Iranian firms beginning to have some influence on the overall economic agenda in Iran, the Middle East, and even global markets. This kind of influence is earned through claims making. Intelligent communications, public relations, and advocacy will allow for the perspective of Iranian firms to diffuse among new stakeholders. Business leaders should strive to be transparent and engage the public through interviews, conference engagements, and philanthropy among other initiatives.

Finally, when links have been formed and perspectives have been shared, Iranian firms and foreign counterparts will hopefully engage in collective action. At a basic level, collective action can represent specific joint-venture projects with multiple stakeholders. At a broader level, collective action will be necessary if Iranian businesses want to shape the future of the country. Only through collective action will businessmen and women emerge as important civil society leaders.

The tactics of brokerage, diffusion, and collective action each deserve their own detailed exploration, and this website will feature such analysis by expert authors in the coming months.

In the meantime, as we anticipate a tentative nuclear agreement, I hope that business leaders in Iran and abroad are galvanized for the incredibly difficult, but also incredibly rewarding work ahead of them. Without their efforts, a nuclear agreement will have little impact on the quality of life enjoyed by the average Iranian. But through enterprising activities such as job creation and the innovation of new goods and services, the promise of a nuclear deal can really come to life.

Photo Credit: Bourse & Bazaar

Iran and Global Trade: Lessons from the 17th Century

◢ Given the immense excitement around the potential lifting of sanctions, it might seem that Iran is opening to the West for the very first time.

◢ But Iran’s history of engagement with Western corporations dates back to the 16th and 17th centuries and history has important lessons for those seeking to enter Iran today.

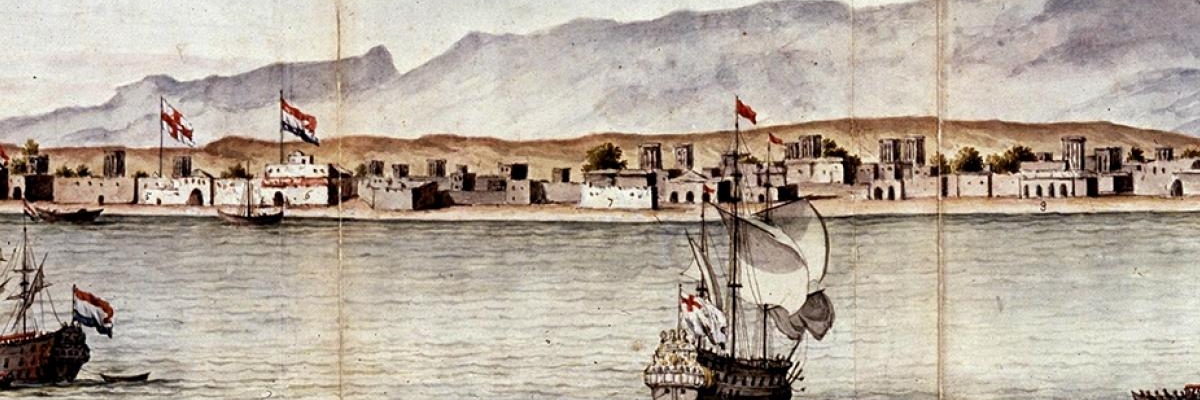

With the prospect of a nuclear agreement and the lifting of sanctions, Iran has become the hottest about-to-emerge market for investors and business leaders. But the anticipated gold rush of major multinational corporations entering the Iranian market is far from new. In fact, Iran’s history of engagement with Western corporations dates back to the 16th and 17th centuries and the reign of the Safavid Shahs, particularly Shah Abbas.

The history of this first “commercial revolution” contains three important lessons for investors and business leaders eyeing Iran today.

Intense competition means no guarantees.

The first Western corporations to do business in Iran date back to the 17th century, when the English East India Company (EIC) and the Dutch Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) integrated Iran into their global trading networks.

But before the English and Dutch built their merchant empires, it was the un-corporatized Portuguese merchants who first brought high-volume maritime trade to Iran and the Indian Ocean region, controlling the strategic ports of Hormuz in Iran, Goa in India, and Malacca in Malaysia.

Fierce competition dictated access to the Iranian market in this period. In fact, although Portuguese traders had an effective monopoly in the 16th century, the coordinated efforts of the EIC and VOC would destroy the Portuguese trading networks. Some decades later, in the early 17th century, merchants from the EIC and VOC began competing directly, and despite the initial advantage of the EIC, which enjoyed a privileged relationship with the royal court, the VOC would wrest control of Persian Gulf trade for the next century.

It is taken for granted that those companies with a presence in Iran today will be best positioned in the post-sanctions period. But as demonstrated by the rise and fall of the Portuguese, the English, and the eventually the Dutch, there are no guarantees when competition intensifies.

A pertinent example that my colleague Daniel Rad discussed in this blog on Monday is the French car manufacturer Peugeot. Despite a decades-long presence in Iran and a dominant market share, increased competition from Chinese and Korean manufacturers such as Kia, Hyundai, and Chery, has been chipping away at Peugeot’s position.

Just as Portuguese traders lost their stronghold on the Iranian market in the 17th century, the current multinational market leaders could lose their privileged positions as more companies eye Iran’s strategic market.

Connective infrastructure is of paramount importance.

The competition between the Portuguese, the EIC, and the VOC at the end of the 16th century was all about establishing global trade networks. By controlling strategic ports, goods could travel more quickly and reliably from sites of cultivation or production in the Far East and to markets for consumption in the Near East and West. More efficiency meant higher profit margins for the companies financing each voyage.

It was through the competition for these strategic ports that Iran gained a key component of its current geostrategic position—access to the Persian Gulf.

Around the time the Portuguese arrived at Hormuz, Safavid rulers had only a tenuous hold on the Southern coast of Iran. The Portuguese faced no real resistance when establishing their port, and even constructed a fortress to protect their position.

The establishment of the first directly Iranian port cities was spurred by the rise of global trade routes in the 16th century. Bandar Abbas, was founded by the Safavid ruler Shah Abbas with cooperation from both the EIC and VOC. British and Dutch forces provided the critical firepower for Persian troops to take the Portuguese fort at Hormuz and claim control over the coastline. Today, Iran has several major ports or bandaran, including Bandar Imam Khomeini, Bandar Abbas, and Chabahar.

In this way, competition over international trade spurred the Iranian state to make a greater effort to connect the country to the world.

Aside from the development of seaports (which will certainly accelerate in a post-sanctions environment— the expansion of Chabahar a particularly ambitious project) the development of Iran’s airports might provide the best modern parallel.

Airport expansion is commonly attributed to rising tourist traffic and growth in Iran’s tourism industry is to be expected. But, the recent rise in the number of business travelers and the expanded need for cargo facilities and logistics infrastructure will be the greatest drivers of airport development.

Even now, at Tehran’s Imam Khomeni International Airport, the best facilities are reserved for “Commercially Important Persons” or CIPs, who have the privilege of travelling through the newest and most modern terminal. The airport’s ambitious $2.8 billion dollar expansion plan is designed to bring the overall standard of facilities in line with those on offer at the dedicated CIP terminal.

The scholar Willem Floor, an expert on Persian Gulf trade, relays the role once played by Bandar Abbas: “In 1628 [the English traveler] Thomas Herbert confirmed the lively, cosmopolitan nature of the new port, where he reports seeing English, Dutch, Danish, Portuguese, Armenian, Georgian, Muscovite, Turkish, Arab, Indian, and Jewish merchants.”

Without the right infrastructure, Iran will struggle to attract a similarly cosmopolitan mixture of international business travellers for the 21st century. New connective infrastructure will be key.

Domestic consumption will drive growth.

When thinking about Safavid Iran’s economy in historical terms, there is a tendency to assume Iran, midway between Europe and the Far East on the famed Silk Road, was just a way station for ships and caravans passing through.

But the Safavid Empire was large and powerful, and competed for regional influence with the Ottomans in the West and the Mughals in the East. As with any empire of its size, the Safavid dynasty had an elaborate court culture, which reached its height of opulence at the time of Shah Abbas.

In this light, Shah Abbas’ cooperation with the English and Dutch merchant corporations enabled Iran itself to emerge as a consumer marketplace. Given the ousting of the Portuguese with the help of the British and French, and victories over Ottoman invaders, “the consolidation of Safavid imperial power” called for an “an enhanced culture of courtly display and consumption of luxury goods” according to a study by historians Derek Bryne, Kevin O’Gorman and Ian Baxter.

With this new courtly display, the upper classes outside the confines of the court began to emulate the new consumerist behaviors. As Rudi Matthee has argued, “Not only was Safavid Iran being incorporated into a new global matrix of commerce and consumption; Iranians played an active role in its very formation by enthusiastically embracing the new consumables and adapting them to their needs and tastes.”

The 17th century commercial revolution that brought varied commodities like “spices, textiles, tin, camphor, Japanese copper, powdered and lump sugar, zinc, indigo, sappanwood, chinaroot, gum lac, benzoin, iron, steel, and sandalwood” to Iran, helped establish the consumerist attitudes seen among Iranians today.

The Safavid ruler and his royal court were the key “early adopters.” As Byrne, O’Gorman, and Baxter have shown, “by working to overcome… cultural inhibitions among the wealthy” the royal court “established a behavioral model, a propensity to consume, that other social strata could later emulate.”

Today, the consumer appetite for foreign goods can be seen in, for example, the increased popularity of shopping malls in Iran. Once confined to small shopping arcades in the wealthier enclaves of northern Tehran, major mall development projects have sprung-up that cater squarely to Iran’s middle class. The kind of aspirational consumerism that only a Western-style mall can provide, through which the middle class can emulate the tastes of the upper class, directly reflects the ways in which the 17th century aristocracy emulated the Shah and his court.

It is likely that Iran’s post-sanctions moment will be characterized by the increased consumption of accessible luxuries. To be clear, items such as smartphones, home appliances, quality cosmetics, the latest fashions, or imported foods have been widely available in Iran. But increased competition for market share by multinational corporations will drive down prices and increase inventories in the country as these corporations cut out middlemen and invest directly into retail opportunities in Iran.

Most importantly, access to these goods will be expanded beyond the major cities of Tehran, Mashhad, Tabriz, Esfahan and Shiraz as supply chains develop. Iran’s middle and lower class consumers will benefit as their purchasing power is stretched further in malls and hypermarkets around the country.

Should the Iranian consumer be unleashed, the domestic purchasing of everyday luxuries will have a significant impact on Iran’s economic growth in an echo of trends from centuries earlier.

The legacy of EIC and VOC are historical evidence of how Western corporations can deeply shape the Iranian marketplace. Investors and business leaders, in looking to history, should come to recognize that they can potentially wield a similar capacity to shape Iran’s post-sanctions future. Whether it is building new infrastructure or influencing consumer culture, the responsibility will be profound.

Photo Credit: Archeonaut

Masters of Montage: Peugeot and Iran's Auto Industry

◢ Iran Khodro (IKCO) announced the re-entry of its French partner PSA Peugeot Citroen into the Iranian automobile market through a new joint venture.

◢ The deal will see 30 percent of jointly produced cars in Iran exported to regional markets. As Iran Khodro’s managing director Hashem Yekke-Zare emphasized, the deal promises to create a regional auto manufacturing hub in the Persian Gulf.

Earlier this month, Iran's leading auto manufacturer, Iran Khodro (IKCO), announced the re-entry of its French joint venture partner PSA Peugeot Citroen into the Iranian automobile market. The new deal carries special significance as it brings with it the potential for new models to be introduced into an Iranian market where designs created in the 1980s are still produced and sold. Additionally, the announced deal would see 30% of Iranian produced Peugeot cars exported to regional markets. As Iran Khodro’s managing director Hashem Yekke-Zare emphasized, the deal promises to create a regional auto manufacturing hub in the Persian Gulf.

Speaking to the breadth of the deal, Yekke-Zare said "the terms and conditions of the contract are not comparable with any of the previously signed agreements with Peugeot." The news of the revised auto-production deal even managed to get Iranian investors excited as shares of Iran Khodro nudged up despite a stock market still sluggish given the lack of positive indicators from the ongoing nuclear negotiations.

While news of the new joint-venture was only reported in the Iranian press, leaving its veracity unclear, the importance of a possible nuclear agreement to a resurgence in automobile manufacturing in Iran, particularly by Renault and Peugeot, has been long anticipated in the international business press.

As part of the new deal, Iran Khodro would be expected to meet Peugeot's production guidelines in an effort to bring the Iranian-made cars in line with the overall international standard. The Peugeot 405 GLX and Peugeot Pars (405 variant) remain big sellers among locally produced cars for their low price and plentiful supply of locally produced spare parts. But the overall build-quality lags behind the French-made versions, and a new manufacturing agreement would seek to remedy this.

Iran’s auto industry has typically relied on the domestic assembly of foreign models, a process known locally by the French term montage. In the mid-twentieth century, Iran Khodro democratized car ownership in Iran by producing the tough and affordable Paykan, which was based on the British Hillman Hunter design. In subsequent years, French brands became more popular.

After the Islamic Revolution of 1979, both Iran Khodro and its main competitor Saipa, struggled to sign contracts with foreign joint venture partners. Eventually, Saipa would begin the domestic assembly of the much maligned, but now ubiquitous South Korean designed Kia Pride. Iran Khodro produced a more premium product in the form of the French designed Peugeot 405 sedan and 206 hatch. All three of these models have been produced in their millions in Iran (IKCO's top year of production was 2011, with 1.7 million vehicles produced).

The sanctions relief permitted for Iran’s automotive industry as part of the 2013 Joint Plan of Action agreement did enable a 43% rise in production in 2014 (after an effective industry shut down in 2012-2013), supported by increased demand due to a stabilizing economy. In terms of market share, available figures from January 2015 suggest that the Peugeot 405 was the top selling car in Iran, outpacing the much cheaper Saipa Pride. The higher-end version of the 405, the Peugeot Pars, was also a strong seller, with a 54% increase in production.

Usually, such strong sales figures would be a signal of a healthy auto industry. But in Iran, the huge demand for these dated models speaks more to an overall dearth of options. 20 year old designs continue to roll off assembly lines, having had only minimal upgrades. Iranian consumers are ready for newer, safer, and more efficient models.

For this reason, excitement over a new deal with Peugeot serves as a reminder of the tough times that had befallen the Iranian automotive production industry over the last decade. If the reports in the Iranian press are to be believed, Peugeot is angling to take advantage of their market dominance by offering new models for montage. Yet, despite the fact that the Peugeot lion logo is affixed to so many cars in Iran, it is hard to say whether Iranians will remain brand loyal when more options arrive in the market. Already, Chinese, Korean, and even domestically designed IKCO models are chipping away at Peugeot’s traditional market share.

Time is not on the company's side. Sooner or later a nuclear deal will be reached, and Iranian car companies small and large, new and old are likely to be offered a wide variety of contracts to produce a wider range of models. How will the Iranian car auto manufacturing look in five years? The jury is out on the direction of the industry, but a look into the state of the competition serves as a potentially useful guide.

Renault, Peugeot's largest competitor in both France and Iran, has also prepared itself for an eventual easing of sanctions. The company recently offered two new "affordable" models to Iranian consumers in the way of the latest versions of the Renault Clio and Captur models.

Renault is actually the French company to most recently introduce a new model to Iran, providing complete knock-down-kits (CKDs) of its Tondar model, sold in Europe as the Dacia Logan. Significantly, Renault’s strategy offers a different look into how cars are produced and sold in Iran. Renault has not employed the same JV tactics that Peugeot has favored, rather licensing its Tondar model for production by three Iranian companies.

Further, the Wall Street Journal reported in January that Renault last year wrote off about €500 million (roughly USD $580 million) that it had accumulated over the years from sales in Iran, stating that under current banking restrictions it cannot repatriate the money. In what would be a bold strategic move, Renault executives have discussed buying a stake in Iranian manufacturer Pars Khodro using some of those stranded funds, according to people familiar with the matter.

Saipa, Iran's second largest producer has also been on the offensive in recent years. The company most notable for the multiple iterations of the 1980's boxy Kia Pride or Saipa 131 has begun producing knock-down-kits from a range of Chinese car manufacturers–nine models in all–along with a four locally produced small cars. The jump in the number of models with Chinese automotive makers underscores the tenuousness of Peugeot’s market advtantage.

Consumer reports suggest that Iranian car buyers will quite happily make the jump to other car brands, and increasingly to Chinese brands. Iranian car buyers have tired of the cars offered by the oligopoly of local producers and yearn for newer models (updated dashboard and facelifted headlights no longer suffice). Moreover, apprehensions of the quality of Chinese cars are slowly diminishing due to the continually improving safety ratings of the updated models.

Modiran Vehicle Manufacturing (MVM) produces local versions of popular low cost models of China's Chery Automobiles. MVM sought to compete directly with IKCO and Peugeot with inexpensive cars for Iranian consumers. Appreciating the up-to-date styling and features, Iranian drivers took up their offer in their droves. These days, many of the smaller vehicle manufacturers in Iran have either started producing or hope to produce variants of Chinese cars. This is likely the largest threat to Peugeot and Iran Khodro in the next 5 to 10 years. This also explains Saipa’s stance of doing away with expenditure on R&D and throwing its lot in with Chinese manufacturers.

The future of Iran’s automotive industry will drive the country’s manufacturing sector at large. Iran’s ability to both diversify its economy, and capitalize on its strong consumer base will depend on the capacity for companies like IKCO and Saipa to produce desirable cars. The principal question is whether the bulk of those cars will be of French, Korean, Chinese, or even domestic designs. The longstanding prevalence of Peugeot may be fortified in the aftermath of a nuclear agreement, but inroads by France’s Renault, Korea’s Kia and Hyundai, and Chinese brands like Chery, may change the composition of Iran’s streets and highways for good.

Photo Credit: Ran When Parked

Why Tech Companies Get Iran Wrong

◢ Iranian consumers already have access to the latest gadgets from the world's leading brands. What they lack are easy shopping experiences and after sales support.

◢ Global technology companies needs to go beyond marketing and brand appeal to win over Iranian consumers through customer service.

Iran has been touted as the greatest untapped market on earth for multinational technology companies. Bar a couple of exceptions like Samsung and HTC few of the international giants have an official presence in the country.

Articles commonly tout a handful of key demographic facts when describing Iran's potential:

Sanctions have kept 77 million Iranian consumers from Western goods and services for decades. And Iran’s population is young (two-thirds of the population is under 35), smart (the highest share of engineering graduates in the world), tech-savvy (the highest internet penetration in the Middle East) and relatively wealthy (the world’s 21st largest economy in 2013, despite sanctions, and a GDP higher than India’s).

But what do these young, smart, tech-savvy, and wealthy consumers really expect from consumer electronics?

Western consumer electronics have been sold in the Iranian market in large quantities since the mid-1990s, in step with the digital revolution. In recent years, the Iranian uptake of the iPhone demonstrates the tendency of Iranian consumers to both adopt new technology quickly, and to develop creative trade connections to ensure supply, sometimes purchasing the latest devices directly from factories in China and elswhere.

For example, I once discovered a Motorola Moto smartphone – a phone made at the time in the United States – in a Tehran store display cabinet brandishing the factory-applied logo of American carrier AT&T.

Items like this imported smartphone show how sanctions hinder both multinational manufacturers and the Iranian consumer. With these grey market imports, Motorola simply cannot gain any real data on Iranian purchasing patterns nor can it understand the local mobile telephone market. It competes in a market in which it has no direct contact with its consumers.

On the other hand, the Iranian consumer is also shortchanged. Their chosen phone lacks company support or warranty and they pay a hefty premium on each device.

In this unusual status quo, American companies, most hindered by sanctions, fare the worst. Their corporate researchers, anticipating the eventual opening of the market, rely on second, third or fourth hand information regurgitated in the media coverage of Iran's commercial potential. This coverage creates a warped view of the domestic Iranian market. Moreover, with the inconsistent and sometimes contractionary market reports produced by Iran's domestic media, this problem is only exacerbated.

But even the absence of many major multinational still doesn't fully explain why so much data on Iran is duff. For that you need to get to the finer points of publicly available reports and then it all starts to become clear.

The onus rests on the international market research firms which produce reports on the Iranian market. These firms use a myriad of unorthodox tactics to gather market data on the domestic Iranian market.

In many instances they simply use fluent Persian language speakers based abroad to read and monitor news reports about specific industries. For more granular information, they might also sometimes cold call Iranian households to ask survey questions about product preferences. These piecemeal methods unfortunately leave big gaps when the finalized data is published.

It is only with on the ground analysis and street-level market reporting that it becomes possible to decipher why certain consumer electronics companies do well in Iran, or why a given device or operating system is the most popular.

Out of all foreign companies it is the South Korean conglomerates which have the best data on Iran, owing to their official precense in the country. They are not likely to share this vital information with their American competition. A recent report on the website of Press TV's– Iran's official English-language international news service–highlights that Samsung in particular is ramping up efforts to strengthen its market position.

However, Apple has so far outpaced all other manufacturers in terms of appeal. This might be unsurprising given that it is now the world's leading smartphone manufacturer. Yet, the Cupertino firm still doesn't have an official representative in the Iranian capital, nor does it offer warranties by third or even fourth party vendors. The grey market imports available on the market are also unusually expensive. But the appeal of the iPhone 6 and Macbook continues to trounce all the other devices available to Iranian consumers.

As part of the global battle with their American foe, Samsung has had an uphill struggle against Apple in Iran. Knowing it lacks the same brand appeal, the Korean firm has invested millions of dollars to establish flagship stores across the country, battling sanctions to offer warranties and even creating Iran's most prolific corporate social responsibility (CSR) policy among foreign companies. But despite all these feathers to their hat, they still have to fight the overall brand power of their main American rival.

Bluechip Japanese electronics firms have also struggled in the Iranian environment in recent years. Some industry insiders admit that Sony, for example, spends one-tenth the amount on marketing budgeted by Samsung. JVC, has all but disappeared from the country's high streets with the last remaining stores stocking dated LCD TVs. Panasonic on the other hand seems to be increasing its presence once again. A flagship store on Shariati Street in Tehran recently saw a complete overhaul.

Yet, massive investment in Iran is no guarantee for success and consumer electronics and technology companies have blundered before. One example can be seen in the case of Nokia in 2009. The Finnish firm reigned supreme among multinationals in the Iranian market, even maintaining a major office on Bucharest Street in Tehran.

However, poorly structured telecommunications deals with their local Iranian partner, misinformation spreading like wildfire, and the firm's general unwillingness to develop a global smartphone strategy quickly put an end to their dominance. No amount of investment could rebuild the tarnished brand in the eyes of the Iranian consumer.

It isn't just hardware or device manufactures who fall short. Microsoft has also squandered an advantage in the brand appeal of its software. Even though the Obama administration eased sanctions on the sale of electronics in 2013, Microsoft has little engagement of Iranian consumers.

Microsoft has continuously punished Iranian users for their use of illegal software, forcing nearly the entire country to rely on unreliable pirated editions purchased cheaply in Iran. The lack of official product support is especially vexing for Iranians as the newest updates, patches, and features remain unavailable for all those unable to purchase an official software license. In fact the problem for the American software firm is so great that thousands of Iranians have petitioned Microsoft to offer official support. Again, despite a dominant market share, negative experiences will continue to color the Iranian view of Microsoft products.

If American, European, and East Asian technology companies want to get a grasp of the Iranian market they are going to need to understand a few things about the average Iranian consumer that data cannot capture. Firstly, as a conversation with any traders or consumers will reveal, the two largest issues for local consumers are warranties and sales support. This is something which foreign manufacturers generally only pay lip service to. For now, it seems Samsung is the exception, having smartly spent huge sums of money on after-sales support. LG comes a close second in terms of support and has also recently stepped up efforts to offer a better consumer experience in major cities like Tehran.

Secondly, rationalization of the shopping experience is a must for most consumers. The traditional bazaar shopping experience continues to this day with many consumers purchasing their electronic items from independent stores, who set inconsistent prices and cannot vouch for the authenticity of their products. This shopping experience leaves a lot to be desired, and often if any problem arises with said items, people have no recourse when something goes awry. The discrepancy between this shopping experience and the carefully calibrated environment of an Apple or Microsoft store abroad must be noted.

In sum, Iranian consumers' requirements are similar to those found in any developed market. Sanctions have not prevented access to the latest technology, but they have made the overall buying experience more strenuous and costly than in perhaps any other market. In a post-sanctions environment, the battle will not be to ensure Iranians purchase devices. Rather, multinational firms must vie to offer the best overall customer service and generate positive brand experiences. The most successful companies will be those that focus less on the hard sales data, and focus more on the more intangible needs and preferences of the Iranian consumer.

In a world of apps and product ecosystems, consumer technology is about more than just the device. The same will become true in Iran.

Photo Credit: Reuters, Raheb Homavandi

Iran, Twitter, and Business: 16 People to Follow

◢ Twitter is a popular platform among pundits, analysts, journalists, and politicians who work on Iran-related issues.

◢ Many of these individuals can be useful points of information to help augment traditional business intelligence practices with a critical awareness of key issues as they develop.

Twitter is popular amongst pundits, analysts, journalists, and politicians as a means to share information and discuss the politics of Iran. But a smaller group of individuals, encompassing business reporters, business leaders, entrepreneurs, and trade officials, also use Twitter to discuss Iran from a commercial perspective. Following members of this group can help augment more traditional business intelligence practices, and ensure a critical awareness of key issues as they develop. By following the right people, one's Twitter feed can become a source of expertly-curated business news and insight that is always up-to-date.

Here are 16 key people to follow if you are interested in Iran’s commercial future.

The Nuclear Negotiations

These accounts offer their followers a great means to track the progress of the nuclear negotiations between Iran and the P5+1.

@AliVaez -Ali Vaez, International Crisis Group

ICG is the only organization to have significantly investigated sanctions rollback scenarios. Their August 2014 report on the nuclear agreements is testament to Vaez’s expertise and overall handle on the negotiations and its many issues.

@lrozen -Laura Rozen, Al Monitor

A tour-de-force on Twitter, Rozen has a knack for distilling the general mood of the nuclear negotiations. Her insights can help followers to stay one step ahead of key developments as the talks progress.

@FaghihiRohollah -Rohollah Faghihi, Entekhab News

On the Iranian side, Faghihi helpfully updates his followers with insightful translations of the key statements made by Iranian officials to the Iranian press. These statements indicate how the nuclear negotiations are being communicated to the domestic audience in Iran.

Sanctions Law and US Policy

Sanctions law is often misunderstood. These accounts can help business leaders trace legal and political risk.

@youbsanctioned -Sam Cutler, Ferrari and Associates

Cullis know the intricacies of US sanctions regulations and use Twitter to comment on news and developments related to Iran sanctions. He commonly identifies misinterpretations of sanctions law by business leaders, journalists, and even policymakers.

@TylerCullis -Tyler Cullis, NIAC

As a legal fellow for the National Iranian American Council, a group that has led advocacy in Washington around sensible application of Iran sanctions, Tyler’s research outlines the relationship between US legislation and the way sanctions are applied in the real world.

Iran Financial Markets

Iran’s financial markets are not widely covered in the usual business and financial press. These accounts demonstrate how Twitter can serve as an alternate source of business intelligence.

@aclIran -ACL

New to Twitter, ACL is one of just a handful of Iran-focused financial services companies with an international profile. Their access to high-quality market research ensures that followers will enjoy access to accurate, granular economic and commercial data.

@FirouzehAsia -Firouzeh Asia

A brokerage on the Tehran Stock Exchnage (TSE), Firouzeh is part of the Turquoise Capital Group, among the first organizations to begin introducing Iran’s securities markets to international investors several years ago. Also follow Turquoise partner Ramin Rabii (@RabiiRamin).

@bazaartehran -Bazaar Business

A news digest, Bazaar Business gathers together the day’s most important news from leading Iranian and international economic publications in one place, saving readers a heap of trouble.

@MortezaRFT -Morteza Ramezanpour, Financial Tribune

The stock market correspondent for Iran's only English-language economic daily, the Financial Tribune, Ramezanpor keeps a close eye on on the TSE.

International Business Reporters

These journalists cover Iran commercial matters for leading international publications. Their reporting drives the general interest in Iran as an emerging market and marks the “must know” developments in the commercial landscape.

@benoitfaucon -Benoit Faucon, The Wall Street Journal

Faucon’s reporting is energetic, and his widely shared account of Apple’s potential entry into the Iranian market demonstrates his knack for finding exciting stories.

@LadaneNasseri -Ladane Nasseri, Bloomberg News

With reporting across Bloomberg’s many quality news products, Nasseri’s contributions have been key to Bloomberg’s expanding coverage of Iran over the last year.

@Najmeh_Tehran -Najmeh Bozorgmehr, The Financial Times

As Tehran correspondent for the vaunted Financial Times, Bozorgmehr has a wide range, including political and human-interest stories. But her business reporting is most unique, with the excellent insight and sourcing one would expect from FT.

@a_merat -Arron Reza Merat, Economist Intelligence Unit

Formerly with The Economist magazine, Merat’s role at EIU reflects the preparations being made my leading market research firms to study Iran more closely and with individuals on the ground in Iran.

@amirpaivar -Amir Paivar, BBC Business News

BBC, with its Persian language service, is one of the few international news agencies with a significant viewership/readership in Iran. Paivar’s bilingual tweets reflect this unique reach.

Iran Startups

Perhaps nothing is more emblematic of the excitement around Iran’s commercial reopening than the media attention on the country’s nascent start-up scene. Unsurprisingly, some of the key start-up players are active of Twitter.

@avatech_ir –Avatech

Avatech is a Tehran-based start-up incubator backed by Iranian VC Sarava. Also follow founder Mohsen Malayeri (@malayeri)

@Startupir -Iran Startups

A startup community in Iran that hosts events around the country. Also follow co-founder Mobin Ranjbar (@MobinRanjbar).

Photo Credit: Bourse & Bazaar

Let It Rule: Imperatives for Central Bank of Iran

◢ In most countries, central bankers wield immense influence over the economy through their monetary policy.

◢ The Central Bank of Iran has struggled to secure the power and independence of its foreign equivalents, hindering economic planning and growth.

“And God said, Let there be light: and there was light.” A central bank’s power is somewhat like God’s, at least in monetary terms, as a former governor of the Central Bank of Iran once said. This is true for the world's most influential central banks such the Fed, ECB, BOJ and BOE or the SNB. The Swiss National Bank's recent move to abandon a self-imposed peg of the Swiss franc against the euro, introduced in 2011, sent the Franc soaring against the Euro by almost 40 percent, is a testament to the power they exert.

But, the CBI is far from wielding the power and independence that its foreign counterparts enjoy.

The bank is under strict financial sanctions, which have diminished its foreign reserves. Thus it has lost face in the foreign exchange market. Gone are the days when remarks by its governor calmed traders. In recent years, even its actions have little effect. In 2012, the bank had to resort to closing down all currency trade in a bid to halt the collapse of the rial, when vows to stabilize exchange rates and financial intervention failed. At that point the bank had overplayed its hand so much so that traders saw the bank reactionary and imprudent. Little has changed in this regard.

Defenders of the bank might counter that the siege on the CBI for allegedly circumventing sanctions against Iran's nuclear energy program is the source of its ineptitude. And yes, having $100 billion trapped overseas does hurt a lot. But that's not all.

Just look at the list of issues the bank is contending with and you'll see that even with a $100 billion, the leopard doesn't change its spots!

It is struggling to bring 7,000 rogue financial institutions, including one Ayandeh bank, under its supervision. The CBI has tried and failed to decrease interest rates for the past year. But, the same institutions have not complied, leading to drainage of deposits from banks towards their coffers.

Furthermore, past monetary decisions by the central bank and the former government have led to tens of billions of dollars of toxic debt on the balance sheets of state-owned commercial lenders, in turn driving them towards property speculation. The central bank is seeking to undo this knot in a civilized way, without undue panic and bankruptcies. Results will materialize slowly, if at all.

When we consider the inability to craft effective policy, at the heart of the matter are the limitations on the central bank's legal powers and its authority to make key decisions.

In most developed countries, monetary policy is the domain of a central bank’s governors. Not so in Iran. The money and credit council, a body within the central bank but controlled by the government, sets monetary policy, not the governor and his deputies. This essentially makes the bank an arm of the Ministry of Finance.

The bank also plays the role of the treasury for the government. It receives oil revenues, and then prints rials and distributes the funds to various government branches. Sometimes the foreign receipt part doesn't take place, thus curbing the bank's control over inflation.

And even when the policies are made, the bank is too feeble to implement them. It doesn't have the capability to exert pressure on banks or the currency market, let alone combat those who defy its commands.

So how can investors and business leaders ask for inflation to be restrained, monetary policy to be set and the currency's value to be stabilized, if they are to rely on such a central bank?

Luckily, the solution is simple enough, at least on paper. A separation of powers is necessary. Monetary policy should be detached from fiscal policy, and the bank should be isolated from politics.

To do so, the bank should be given full autonomy on monetary matters, a structure similar to that enjoyed by its counterparts in developed nations. A system of governance, where by all three branches of government have a degree of influence in the bank's governance would better guarantee the bank's autonomy. But this would require a change in the constitution, a lengthy and difficult process.

Furthermore, the central bank's legal clout and ability to exert power on its turf needs augmentation. Its influence has to cut through the lobbying of vested interests. Its responses to crime must become rapid. For this it needs more legal powers and a wider array of financial tools to help it set and oversee monetary policy. Again lawmakers must empower the bank for the benefit of investor, business leaders, and the economy at large.

Many officials in the current administration have expressed their desire to give CBI greater autonomy and new legislation is under work to give the bank some new powers. But a half-hearted will not be effective. What is needed is a fully independent central bank, as enshrined in law and in the deference of the financial sector at large. After all a strong and independent central bank will help iron-out the full range of economic policies. We ought to let the governor rule his domain.

Photo Credit: mebanknotes.com

Negotiating Iran: Paving the Way for Foreign Investment

◢ Iran has spent decades pursuing self-sufficiency across major industries in what has been called a “resistance economy.”

◢ This development strategy must change if the country is going to attract much needed foreign direct investment post-sanctions.

For decades, Iran has largely gone it alone in developing its industries. If there were a global economic self-sufficiency index, Iran would be right at the top. This self-sufficiency, although impressive to the outside world, has nonetheless encouraged practices and processes that are inconsistent with global norms. As Iran and the P5+1 hammer out a nuclear deal the Islamic Republic contemplates a post-sanctions environment which will undoubtedly call for a revision of the country's economic and development strategies. Crucial to this transition will be a strategy to attract more foreign direct investment.

Foreign investors have done their homework on identifying both the unprecedented investment opportunities of a post-sanctions Iran as well as the obstacles and fundamental challenges. Given the Islamic Republic’s distinct profile and potential for growth, Iran is poised to become the next frontier market to be developed. But more homework will need to be done on Iran in order for investors to gain FDI contracts.

Although not unique to Iran, three key aspects of FDI negotiations are worth noting for investors: the capabilities and character of Iranian industries, the Islamic Republic’s hierarchy of values and the country’s overall post-sanctions economic and development strategies. Each of these aspects needs to be understood in depth and in relation to the others in order for foreign investors to gain favorable FDI contracts.

Below is a broad understanding of the three aspects of FDI negotiations specific to Iran that will be explored in greater detail in subsequent articles.

Capabilities and Characteristics of Iranian Industries

Iranian industries yield some impressive production numbers. For example, despite suffering under sanctions, Iran’s auto industry will produce 1.1 million cars in the current Iranian year which ends on March 21, 2015; up from a low of 737,000 in 2013 and nearly at the level of 1.6 million in 2011, when the EU introduced new sanctions. Save the inclusion of some components like engines and select electronics, what is significant is that this level of production in the auto industry was achieved without the benefit of value added exports afforded through a broader global value chain.

But this achievement is a double-edged sword. The vast majority of cars produced were for domestic consumption rather than for export. Moreover, decades of working largely outside of the global economy has bred production techniques and practices that might be unfamiliar to the network of global value chains in both Europe and Asia.

Consequently, the practices, techniques and overall ways of doing doing business for a variety of Iranian industries fall short of global norms (This situation is not unlike the policies of Import substitution industrialization popular in Latin American economies in the 1970s and 1980s). Before getting to the negotiating table, foreign investors will need to do their homework on not just the business opportunity but also the character and level of variance of business practices of their respective industries in Iran. For example, having been accustomed to working with a domestic set of suppliers, Iranian manufacturers will need to get accustomed to working with an international set of suppliers. Once the capabilities and characteristics of Iranian industries are understood, investors will be in a better position to offer the knowledge and technology transfer that the Islamic Republic desires in exchange for contracts.

Iran’s Hierarchy of Values

Having developed an industrial base to the level it has, Iran’s hierarchy of values brought to FDI negotiations will differ from that of other lesser developed countries. The likelihood of a walkout by Iranian officials from the negotiation room might be high with the rationale being the Islamic Republic could go without the investment and simply continue to muddle through as they have been. Hence, foreign investors need to have an adequate understanding of the Iran’s hierarchy of values. For example, Iranian manufacturers may prefer to acquire new capital for their factories rather than adopt new manufacturing techniques.

A lack of understanding also seems to be evident in the ongoing negotiations regarding Iran’s nuclear program which is currently on its second months-long extension. Foreign investors will need to have done their homework on understanding what specific values Iranian officials hold relative to them and offer a package of value added technology and knowledge transfers that reflect this understanding. In sum, Iranian decision makers more than the leaders of other lesser developed countries put more weight on outsiders understanding their hierarchy of values reasoning that the Islamic Republic could almost always return to an ‘economy of resistance’.

Post-Sanctions Economic and Development Strategies

As it looks now, all signs lead to a gradual lifting of sanctions on Iran which will in turn steadily open Iran to the global economy over years if not a decade or more. Iranian decision makers will need to overhaul the country’s economic and development strategies in order to accommodate the rapid increase in FDI inflows as well as the country’s broader integration into the global economy. The process will inevitably appear shambolic, haphazard and/or incongruent and occur at a seemingly breakneck speed. But if the foreign investor has done their homework knowing which knowledge and technology transfers Iran seeks at which phase and has a firm grasp of the hierarchy of values of Iranian decision makers vis-a-vis their own, they are more likely to be seen as part and parcel to Iran’s economic and development strategies and consequently granted FDI contracts. Finally, given the Islamic Republic’s penchant to go it alone if need be, first-mover advantage could be especially important and lucrative for foreign investors that are granted contracts.

Conclusion

Negotiations are about knowing what the other side wants in order to reach a favorable agreement. They tend to go smoothly with both sides contributing positively to the other side so as long as there is a thorough understanding of the other. If foreign investors do their homework the intricacies on the role of FDI in Iran’s post-sanctions economic and development strategies coupled with an understanding of the hierarchy of values of Iranian decision makers they can gain an advantage at the negotiating table.

Photo Credit: Financial Tribune

Risky Business: Four Categories of Iran Risk

◢ Managing risk is a key part of an Iran market entry strategy.

◢ There are four major categories of risk to consider: commercial, legal, political, and reputational.

It must be commonplace in meetings where opportunities for business development or investment in Iran are being discussed. Suddenly it becomes apparent that the pitch was half-baked-- it didn’t include an assessment of risks. With a simple question like “What’s the firm’s reputation?” or even “Is it legal?” the pitch falls flat.

A more systematic and proactive approach to risk assessment can avoid these pitfalls. An assessment should begin with four main categories of risk: commercial, legal, reputational, and political. Each of these categories needs to be explored in depth and in relation to the others in order to craft a useful and durable business development strategy. Even if you aren’t an expert in any of these categories (I certainly am not), having a structured approach helps identify gaps in knowledge early so that the right information can be sourced and solutions can be crafted before a problem arises or a tough question comes up in a pitch meeting.

Below is a basic introduction to the four types of business risk in the Iranian context, which will hopefully be explored in greater detail in subsequent articles.

1. Commercial Risk

The greatest challenge in evaluating commercial risk in Iran is the way expectations can quickly outpace reality in anticipation of a historic nuclear deal.

Articles in the The Economist, Wall Street Journal, Time, and other publications have trumpeted the impending “gold rush” or “bonanza” that would ensure if Iran is reintroduced into global markets for goods, services, and capital. The enthusiastic reporting of the many possible macroeconomic drivers of Iranian growth—a young population, an untapped manufacturing base, decent purchasing power, limited government debt etc.— makes it seem like investment in Iran is a “safe bet.”

But the reality is that within the positive forecasting for Iran on a macro scale, investors, business leaders, and entrepreneurs— whether foreign or Iranian—need to heed the dynamics of the micro scale. Investment opportunities ought to be judged on their own terms, and not solely in relation to the bigger picture of potential Iran growth.

What does this mean in practice? Whatever the opportunity in question, a commercial risk analysis needs to be done to ensure that the opportunity remains viable for a wide range of macroeconomic scenarios. It is tempting to treat investments as a “safe bet” because the macro projections are so good. For example, an investor might think that a heavily leveraged buy-out of a consumer goods factory, even one that is inefficient and poorly managed, would be worthwhile because consumer demand is likely to surge in the aftermath of the deal—an inefficient factory can still deliver good margins if the price of goods rises high enough. But what happens when this belief leads the investor to shirk the responsibility to make the factory operate better, whether through better management or equipment upgrades? The factory investment remains exposed to a fundamental commercial risk, and if consumer demand does not materialize, the heavily leveraged bet is lost.

Certainly, emerging markets investors in markets like China, Brazil, India and South Africa have the appetite for such risky bets, and sometimes they are able to execute aggressive strategies to great success. But if overly aggressive approaches become widespread in the post-sanctions investment landscape, the tendency will be to ignore or discount the true commercial risk.

Iran only has one chance to emerge from years of isolation and to position itself for long-term prosperity. The last thing the country needs is the wild speculation and risk-taking that typified foreign investment in Russia in the mid-nineties. The “only way is up” attitude towards economic growth ignores the necessary volatility in any major economic reorientation, and also overshadows the reality that a dud business is a dud business regardless of how good the economy might get. The goal should be mitigate commercial risk at the micro level so that the enterprise can prudently navigate any macroeconomic fluctuations.

2. Legal Risk

Iran remains subject to the most advanced and comprehensive sanctions program ever instituted. So it is perhaps especially frustrating that entrepreneurs and investors get excited about commercial opportunities before they have a close look at the legalities. When the “post-sanctions” future is imagined, the process of sanctions relief is often simplified as though sanctions will go from “on” to “off.” But the real opportunities will lie in navigating the legal landscape in order to find the viable opportunities first.

Sanctions regulations are complex and were legislated in a messy way. How they will be rolled back remains a point of debate. But generally speaking, where US sanctions go, EU and UN sanctions will largely follow. What is clear is that the rollback of sanctions will likely be a phased process, and therefore the legal landscape will be constantly evolving even in what seems to be a “post-sanctions” moment.

In the meantime, companies will be tempted to try and “outsmart” sanctions. But this is foolhardy. Compliance is important, and companies should invest in the best legal expertise available on an ongoing basis to learn how to craft an adaptive, compliant business strategy. Failure to comply could mean drastic and long-lasting commercial, reputational, and political damage. It is a bad habit shared by many firms that in order to keep costs low, the lawyer is only hired when the contracts are being drafted.

Additionally, companies shouldn’t forget about the need to comply with Iran’s domestic laws. There is a tendency for multinational firms to flout domestic laws when entering emerging markets. Usually, the perception of lax enforcement and corruption allows companies to think that domestic laws can be heeded selectively. This is also foolhardy. Not only is Iran’s enforcement capacity greater than the average emerging market (it has very strong state institutions, despite levels of corruption), but failure to pay taxes, ensure safety, or abide by environmental protections will earn the ire of the highly-educated Iranian public, who should be respected even more than the prosecutors.

3. Reputational Risk

I touched on the topic of reputational risk in this November article for LobeLog, and I consider it one of the most fascinating challenges of doing business in Iran. The commercial and legal risk present in Iran is commensurate with levels in numerous markets, but the level of reputational risk is perhaps the highest in the world.

A poll published by BBC World Service in June 2014 identified Iran as the most “unfavorably viewed country” by individuals worldwide. Certainly, much of the international criticism is deserved and companies need to be honest with their customers, employees, and shareholders about their corporate responsibility to support positive social outcomes in all markets, including Iran.

But from the standpoint of business development it is worth considering the specific allergic reaction often exhibited when the ideas of “Iran” and “business” are combined. Special interest groups use public campaigns to name and shame companies that do legal business in Iran. Sometimes even humanitarian trade is targeted. So when we consider the idea of normalization, we are really discussing a new normal in which the combination of the ideas “Iran” and “business” is no longer the cause for concern or condemnation.

In practical terms, managing reputational risk will require savvy branding and an excellent communications and public relations strategy. This involves everything from redesigned websites to better disclosure of company activities, announced through new mechanisms of corporate communications. Transparency will be key in order to assuage negative perceptions and present a new normal of a responsible and resurgent business community.

4. Political Risk

The fourth and final category of risk is perhaps the most difficult to evaluate. Political risk is about “street smarts”— understanding the commercial landscape of a country like Iran in a very deep way, capturing the political, social and cultural dimensions. Those seeking to do business in Iran will have a lot to learn in little time.

At the macro level, political debates around privatization and foreign ownership may impact how commercial and contract law is carried out, but there are actually existing laws written to protect foreign investment and private enterprise—they just have had limited use in a period of low FDI. Firms will need to develop skills in government relations to ensure they stay on top of these debates and the consequences for their business.

Looking to the micro level, Iranian society places great importance on personal or institutional reputation and pride. Any partnership or venture is judged on the reputation of its constituent parties. But rather than seeing reputation as a question of branding, this is a more political understanding of “reputation.”

For example, a certain individual or company might be the most commercially powerful of among the potential partners, but may also have a more questionable reputation within the industry. This partner may be best positioned to mitigate commercial risk in a given venture, but how does the politics of a potential partnership effect reputational or legal risk in the medium to long term? Would a company that is less commercially powerful, but held in higher esteem actually make a better partner?

To be clear, the need to make such political evaluations is not a trait unique to Iran. Even Silicon Valley is a place where the partner you choose or the investor you secure can drastically alter the trajectory for success. In Iran, as in Silicon Valley, political risk means knowing who are the key actors, how they are perceived, and the resources they are able to mobilize. But for a foreign investor or firm, the learning curve in a new market like Iran will be especially steep.

Conclusion

Looking at these four categories holistically, responsible companies will seek to turn risks into strengths. A proactive and careful approach to developing the commercial, legal, reputational, and political facets of a business development strategy can offer firms a competitive edge in the marketplace. Mitigating risks can be expensive and time-consuming, and may require seeking analysts, lawyers, PR consultants or other experts to help fill gaps in knowledge. But companies that can internalize and deeply understand risk/reward calculations for the new phase of Iran’s development will reap immense rewards.

Photo Credit: Morteza Nikoubazi/Reuters