Iran Trade Mechanism INSTEX is Shutting Down

At the end of January, the board of Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX) took the decision to liquidate the company.

At the end of January, the board of the Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX) took the decision to liquidate the company. Established in January 2019 by the United Kingdom, France, and Germany, INSTEX’s shareholders later came to include the governments of Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands, Finland, Spain, Sweden, and Norway.

The state-owned company had a unique mission. It was created in response to the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal in May 2018. European officials understood that the reimposition of US sanctions would impede European trade with Iran. The nuclear deal was a straightforward bargain. Iran had agreed to limits on its civilian nuclear programme in exchange for the economic benefits of sanctions relief. If European firms were unwilling or unable to trade with Iran, that basic quid-pro-quo would be undermined. For this reason, supporting trade with Iran was seen as a national security priority.

In August 2018, EU high representative Federica Mogherini and foreign ministers Jean-Yves Le Drian of France, Heiko Maas of Germany, and Jeremy Hunt of the United Kingdom, issued a joint statement in which they committed to preserve “effective financial channels with Iran, and the continuation of Iran’s export of oil and gas” in the face of the returning US sanctions. They pointed to a “European initiative to establish a special purpose vehicle” that would “enable continued sanctions lifting to reach Iran and allow for European exporters and importers to pursue legitimate trade.”

In November 2018, when the basic parameters of a special purpose vehicle were still being formulated by European officials, I co-authored the first public white paper explaining why establishing such a company made sense. Conversations with European and Iranian bankers and executives had made clear to me that trade intermediation methods were being widely used to get around the lack of adequate financial channels between Europe and Iran. If these methods could be packaged as a service by an entity backed by European governments, it would reassure European companies about remaining engaged in the Iranian market, while also reducing costs.

A few months later, INSTEX was founded. In the beginning, the company was run by the Iran desks at the EU and E3 foreign ministries. The officials tasked with working on INSTEX, who were often very junior, quickly realised they had little knowledge of the mechanics of EU-Iran trade. When they sought to enlist help from colleagues at finance ministries and central banks, they frequently met resistance. Many European technocrats were reluctant to support a project which had the overt aim of blunting US sanctions power, even at a time when figures such as French finance minister Bruno Le Maire and Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte were making bold statements about the need for European economic sovereignty. Even INSTEX’s inaugural managing director, Per Fischer, departed given concerns over his association with a company that had been maligned by American officials as a sanctions busting scheme. Then, in May 2019, when the Trump administration cancelled a set of sanctions waivers, European purchases of Iranian oil ended. That left INSTEX as Europe’s only gambit to preserve at least some of the economic benefits of the nuclear deal for Iran.

Later that year, INSTEX hired its first real team after a new group of European governments joined as shareholders and injected new capital into the company. For a time, things looked more promising. Under the newly appointed president, former German diplomat Michael Bock, a small group of talented individuals worked to define INSTEX’s mission and build a commercial case for the company’s operation. Their efforts led to INSTEX’s first transaction, which was completed in March 2020—the sale of around EUR 500,000 worth of blood treatment medication. The political pressure to provide Iran some gesture of tangible support during the pandemic had also greased the wheels in European governments.

But many considered the INSTEX project doomed even before the first transaction was completed. Certainly, Iranian officials were derisive of the special purpose vehicle. Given that Europe had failed to sustain its imports of Iranian oil and was unable to use INSTEX for that purpose, focusing instead on humanitarian trade, Iranian officials dismissed the effort, even after the feasibility of the special purpose vehicle was proven. That it took more than a year to process the first transaction also meant that the Europeans missed their chance to fill the vacuum caused by the US withdrawal from the nuclear agreement. Without full cooperation from its Iranian counterpart, which was called the Special Trade and Finance Instrument (STFI), INSTEX could not reliably net the monies owed by European importers to Iranian exporters with those owed by Iranian exporters to European importers.

European officials will no doubt blame Iran for the fact that INSTEX failed, and it is true that the Iranian government never fully appreciated the political significance of European states taking concrete steps to counteract even the indirect effects of US sanctions. Of course, the decision to liquidate the company follows a spate of recent actions by the Iranian government—nuclear escalation, the sale of drones to Russia, and the brutal repression of protests—that make the continued operation of INSTEX politically untenable.

But most of the blame for INSTEX’s failure must lie with the Europeans—the company’s demise predates Iran’s recent transgressions. European officials promised a historic project to assert their economic sovereignty, but they never really committed to that undertaking. A mechanism intended to support billions of dollars in bilateral trade was provided paltry investment. European governments never figured out how to give INSTEX access to the euro liquidity needed to account for the fact that Europe runs a major trade surplus with Iran when oil sales are zeroed out. For the Iranians, this alone was the evidence that European leaders saw INSTEX as a political gesture that might placate Tehran, rather than an economic instrument that would bolster Iran’s economy in the face of Trump’s “maximum pressure.”

Paradoxically, Iran will lose nothing as the liquidators shut down INSTEX, quietly selling the few assets the company had accumulated—laptops, office chairs, and perhaps some nifty pens. It is Europe that is losing out. INSTEX was supposed to be a testbed for new ways of facilitating trade without relying on risk-averse banks to process cross border transactions. Successful innovation in this area would have given a new dimension to European economic diplomacy and helped Europe assert the power of the euro in global trade.

With the writing on wall, INSTEX’s management made one final attempt to give the company a future. Beginning in 2021, the company pursued a French banking license—a pivot that INSTEX’s board had approved on a provisional basis, but which was halted in early 2022. It is hard to overstate how significant it would have been had INSTEX emerged as a state-owned bank with a specific mandate to process payments on behalf of European companies that wish to work in high-risk jurisdictions, including those under broad US sanctions programme. Such a bank could have become a powerful tool for Europe to assert its economic might in the face of US sanctions. Moreover, it would even have been useful in cases where Europe is applying sanctions, like Russia. After all, a commitment to humanitarianism means that goods such as food and medicine must continue to be bought and sold even when most transactions with a given country are prohibited. INSTEX could have helped make European sanctions powers more targeted and more humane.

For a company that managed just one transaction, a surprising amount has been written about INSTEX. It has been the subject of news reports, think pieces, and academic articles. Even if many people struggled to understand what the special purpose vehicle aimed to do, its existence was novel and therefore noteworthy. For those insiders directly involved in the company’s saga, and for those of us who have closely followed from the outside, the main takeaway seems to be that there is much yet to be learned about the complex ways in which US sanctions impact European policy towards countries like Iran, through both political and economic vectors. In this respect, INSTEX did achieve something. A group of technocrats in European foreign ministries and finance ministries learned valuable lessons, often reluctantly and with great difficulty, about the limits of Europe’s economic sovereignty. Whether those lessons can be institutionalised remains to be seen. But a fuller post-mortem on INSTEX would no doubt offer important lessons for the future of European economic power in a world dominated by US sanctions. Learning those lessons would be its own special purpose.

Photo: Wikicommons

What Role Do Economic Conferences Play in Uzbekistan’s Development?

Uzbekistan is seeking a dialogue with the world and economic conference can serve to build trust and generate credibility.

Back in November, I travelled to Samarkand to attend the Uzbekistan Economic Forum. I had been to the ancient city nearly a dozen times, but this was my first professional event there. The Uzbekistan Economic Forum did not suddenly convince everyone that Uzbekistan is a special country. But it did show that Uzbekistan was becoming a more normal one.

Not everyone in Uzbekistan was happy with the conference. Some journalists and bloggers questioned why Uzbekistan’s government needed to convene yet another major and costly event. Others wondered if the return on investment would be worth it. Concerningly, the costs of the forum were not disclosed. Clearly, the organisers could have done a better job in publicly communicating the rationale for such a large event and why such conferences matter. To me, there are three reasons why they do.

First, Uzbekistan needs to foster regular dialogue with businesses partners, investors, and lenders who are independent from the government. Such actors are accountable to their shareholders, are subject to intense international media scrutiny, and must follow varied regulations around governance and sustainibility. Therefore, they can audit Uzbekistan’s achievements and shortcomings more honestly, generating important information for local media and civil society.

A country whose debt burden is equal to 40 percent of its economic output must be open to scrutiny of its economic policies and institutions. The forum’s thoughtful programme presented the opportunity for such scrutiny, with topics ranging from political reforms to economic inclusivity. The organizers brought in people who could ask tough questions (including former CNN and Bloomberg journalists) as chairpersons for the panel discussions. Senior representatives from the IMF, IFC, World Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), Asian Development Bank, Asian Infrastructure and Investments Bank, regional central bankers, financiers, investors, and many consultants featured on these panels.

There was a time when frankness came at a cost. In May 2003, panelists from the EBRD, which was leading Uzbekistan through its protracted post-communist transition, spoke truthfully about the country’s economic and political shortcomings at the Annual Meeting in Tashkent. By 2005, EBRD war hardly making any loans in Uzbekistan and by 2007 it had exited the country altogether, unable to operate in an environment in which the authorities demanded deference. It was not until a decade later that EBRD returned to Uzbekistan. Today, the bank has 65 active projects with over EUR 2 billion in total portfolio value. With that much at stake, it is reasonable to expect that the EBRD and peer institutions will continue to speak up, especially as its activists continue to push the bank to live-up to its pro-democracy mandate.

Second, Uzbekistan needs a platform to prove its bureaucratic capacity, as it seeks to stay the course of increasingly difficult structural reforms. In contrast to heavily protocolled political events with predetermined outcomes such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization or Inter-Parliamentary Assembly, participants of economic forums in Uzbekistan are more demanding, represent diverse stakeholders, and care about performance dynamics. The newly formed Ministry of Economy and Finance, the Ministry of Labor and Poverty Reduction, and the Ministry of Justice—which oversee social policy—face new challenges every day. The nominally independent Central Bank and the judiciary are undergoing significant changes with unclear outcomes. They will all need to prove that they can uphold Uzbekistan’s domestic and international commitments and pay the bills.

At the same time, reform-minded public administrators themselves need businesses, civil society groups, and international professionals to get their president's attention in the highly centralized system. In Uzbekistan, the presidential administration can be reactive, prioritizing issues in response to media coverage, expert commentary, formal reports, and face-to-face meetings. It is no secret that certain business leaders may enjoy better access to the president that many ministers do not have. So, it is good when investors are both long-term thinkers and legally bound to seek clean deals. These investors and reform-minded public administrators can form coalitions as part of two-level game through which domestic reformers in transition economies find the means with which to amplify their voices.

Alongside many countries “stuck in transition,” the Uzbek government continues to face challenges outlined by the IMF in its 2014 review marking 25 years after the end of communism in Europe. Uzbekistan needs to reign in its exorbitant public expenditures, improve the business climate, enable market competition, enforce state divestment, and ensure rule of law. It was reassuring that almost all keynote speakers in Samarkand said the same. By the end of the first day (most discussions can be watched freely online), it was clear that there was broad consensus about what needs to happen to enable prosperity.

The Uzbek ministers and senior officials speaking at the conference shared this consensus and acknowledged problems. Some even joked, earning sincere laughter from the diverse audience. Importantly, the conference was held in Uzbek and English — this was more than political symbolism. Russia’s war on Ukraine has had varied effects on the Uzbek economy. These have been mostly negative (e.g. reduced financial inflows and increased social policy burden), though there have been a few silver linings (e.g. capital relocation, higher commodity prices, and parallel exports). After independence, Uzbekistan, like other post-Soviet states, pursued legislative and regulatory harmonisation with Moscow. But the country’s bureaucracy is starting to look beyond Russia. The use of the Uzbek language helps the central government connect to a wider swath of society. The use of English, meanwhile, represents a search for a wider cooperation with foreign countries.

Finally, these conferences help set expectations—and there are many expectations being set. That Uzbekistan will privatise the promised 1,000 more state-owned enterprises. That utility and energy prices will be liberalized. That the economic growth will be increasingly supported by foreign direct investment rather than direct borrowing. That more will be done to empower and separate the judiciary from the executive branches. That the Oliy Majlis, Uzbekistan’s legislature, will pass new competition law and that it will be signed. That Uzbek GDP will rise to USD 100 billion by 2026 and USD 160 billion by 2030. That the country embraces a free market economy, trusting that its people can achieve more with less state intervention. Whether Uzbekistan meets these high expectations is something that can be assessed when it is time to gather for another forum.

Uzbekistan is seeking a dialogue with the world. We can quibble about the optics of such conferences, but they do serve to build trust and generate credibility. There was a time when economic conferences in Uzbekistan had long titles, glorified the present, and discussed the future in only abstract terms. Back then, the desired outcome was applause—those conferences played no role in the country’s economic development. In Samarkand, a different kind of conference took place.

Photo: Uzbekistan Economic Forum

How Shifts on Instagram Drove Iran's 'Mahsa Moment'

Iranians are using Instagram for political activism like never before. But these changes were not sudden. The “Mahsa Moment” was driven by user trends on social media that have been years in the making.

This article was originally published in Persian.

In a narrative crafted by various political and intellectual currents, the “Iranian Instagram” is often presented as a means of depoliticising the attitudes and behaviours of the Iranian people, with its users engaging in vulgar content, falling for false news and claims, cursing at famous figures, and morbidly posting accounts of the more attractive sides of their daily lives. This same formulation is used by the conservative movement (also called the Principalists movement) to realise their policy of "organisation" and "protection" of the Internet. Using comparable language, pro-change political currents also direct users to ostensibly more political platforms, such as Twitter and Clubhouse. However, if this is the case, why has Instagram become one of the most prominent platforms for expressing and even organising political protests in the “Mahsa Moment?”

The simplest and shortest response to this question is to attribute everything that has occurred over the past two to three months to the Islamic Republic's enemies. This response has been heard repeatedly on official domestic media in recent months. Some of the self-proclaimed leaders of the people's protests in the media outside of Iran have given the same answer in different words, claiming that these events are the result of their years of hard work and meticulous planning. This type of analysis of people's collective actions is not only unenlightening and ineffectual but is a significant contributor to the current crisis.

However, another approach might be to temporarily set aside preconceived notions about online social networks in favour of a more empirically grounded and scientifically sound approach to answering this question. A portion of the answer to this question can be found by analysing the changing trends on Iranian Instagram.

Those of you who have been following along for the past three years may recall that I began a longitudinal study of Iranian Instagram in 2019 and have since published an analytical update three times in the early fall of 2019, 2020, and 2021. This year, data collection and analysis took longer than usual due to Internet filtering and interruptions, delaying the report preparation for the fourth phase of this research.

With these explanations, the findings of the fourth consecutive year of this research will be presented within the context of the question posed at the beginning of the report. The findings of this study demonstrate that the transformation of the Iranian Instagram space at the “Mahsa Moment” into a platform for online protests and the organisation of offline protests cannot be attributed to a pre-planned project. Rather, we must understand and analyse this phenomenon in light of the agency of users and the gradual changes that have occurred on Instagram in Iran over the past few years. In addition, despite tightening restrictions over the past year, Iranian Instagram continues on its path, both quantitatively and qualitatively, consistent with the previously optimistic changes.

Figure 1 depicts the frequency of active popular Iranian Instagram pages between 2019 and 2022. Despite the tightening of various restrictions facing Iranian users on Instagram, the number of active Iranian pages on Instagram with more than 500,000 followers increased by 17% in 2022, reaching 2,654.

Figure 1: Frequency of active Iranian Instagram pages with over 500k followers from 2019 to 2022

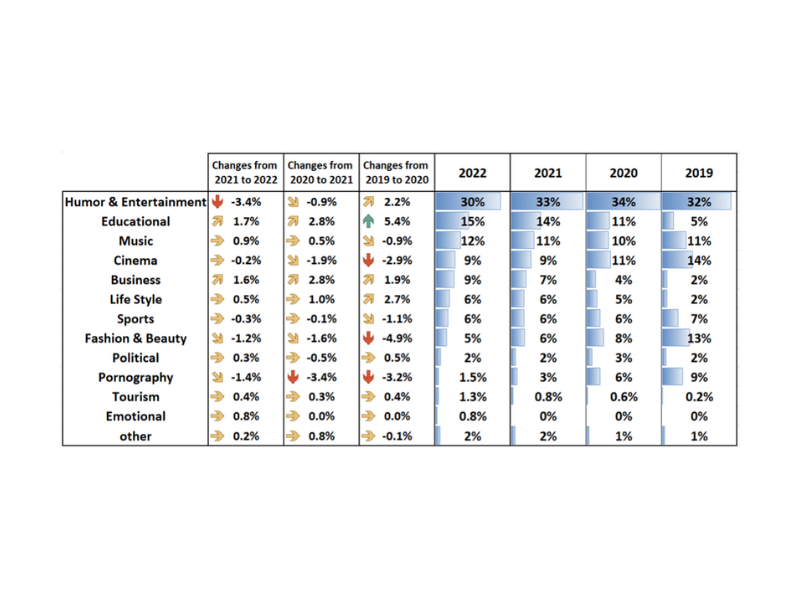

As displayed in Table 1, the share of "humour and entertainment", "fashion and beauty", and "pornography" pages among the most popular Iranian Instagram pages has decreased significantly over the past year. While the decline in "fashion and beauty" and "pornography" pages continues a longer trend, the declining ratio of "humour and entertainment" pages on Iranian Instagram over the past year is something new. In contrast, the percentage of "educational" and "business" Instagram pages has continued to rise in 2022.

The appearance of "tourism" and "emotional" pages on popular Iranian Instagram pages in 2022 is another notable change. On the tourism pages, content pertaining to tourism in various regions of Iran and the world is published, whereas, on the emotional pages, content that represents human feelings and emotions are published.

Table 1: Share of popular pages by primary subject from 2019 to 2022

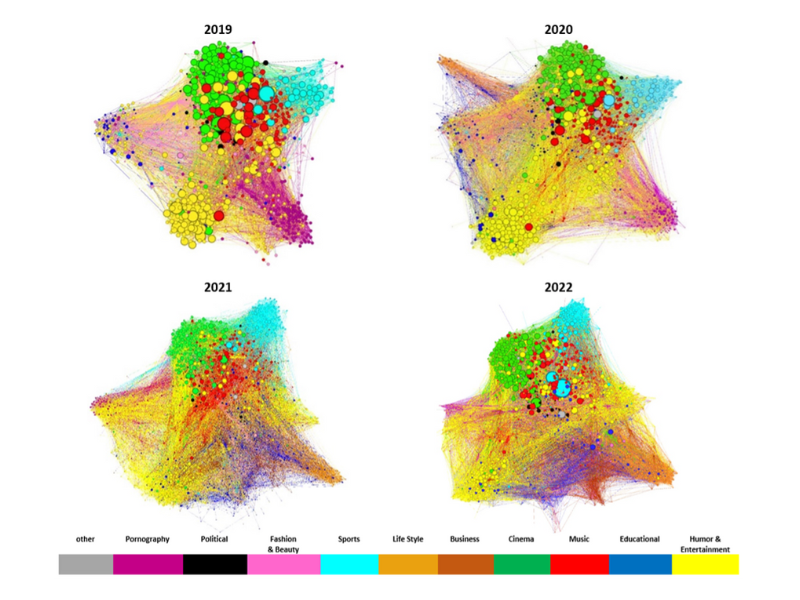

The trend of changes in the network of relationships between popular Iranian Instagram pages is illustrated in Figure 2 using the Indegree Index. When comparing the changing trend of the graphs from 2019 to 2022, we observe that education (dark blue), business (brown), lifestyle (orange), and fashion and beauty (pink) pages have become increasingly integrated within their respective fields and have distanced themselves from other fields. In the upper portion of the graphs, from 2019 to 2022, we notice an increase in the intertwining of sports screens (pale blue), movies (green), and music (red). In other words, these three types of popular accounts—also known as "celebrity” accounts—have gradually shaped a field that is related to issues outside of their profession. In this multifaceted field, in addition to celebrity pages, there are humour, entertainment, political, and social pages (yellow, black, and grey).

Figure 2: Changes in the network of relationships between popular Iranian Instagram pages from 2019 to 2022, as measured by the Indegree Index

Figure 3 displays the ten Iranian Instagram influencers with the highest authority based on the Authority index. All of these individuals belong to one of the three categories: sports, film, or music. These three categories also overlap. Moreover, with the exception of two individuals, the rest post additional content on the page related to their audience's political, economic, and social concerns and demands, as well as their profession and area of expertise. Let us refer to this type of celebrity as a "celebrity-activist.”

By a significant margin, Ali Karimi has the highest authority among the most popular Iranian Instagram pages, followed by Ali Daei, Golshifteh Farahani, Javad Ezzati, Amir Jafari, Bahram Afshari, Mahnaz Afshar, Majid Salehi, Parviz Parastui, and Reza Sadeghi.

Figure 3: Network relations between popular Iranian Instagram pages in 2022, as per the Authority Index

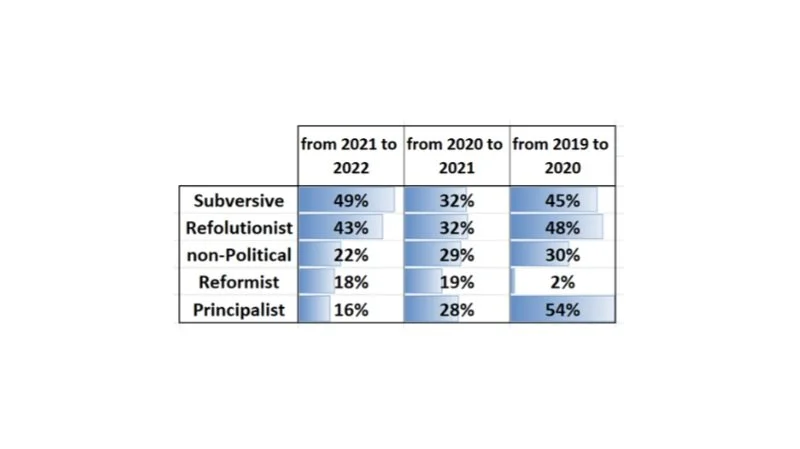

By reflecting on Table 2 and reviewing Table 1, we can gain a greater appreciation for the reasons why celebrity-activists on Iranian Instagram gain authority. Table 2 demonstrates that the number of followers of popular subversive pages has increased by 49% over the past year. This index was 43% for refolutionist (neither revolutionist nor reformist), 22% for non-politicals, 18% for reformists, and 16% for conservatives (Principalists). Comparing these statistics to those from previous years reveals that the notion of protesting the current political situation has become increasingly popular and a sought-after item on Iranian Instagram over the past year.

In contrast, as shown in Table 1, the proportion of political pages (individuals, groups, or organisations professionally engaged in political activity) among the most popular Iranian Instagram pages did not change significantly between 2019 and 2022, fluctuating by approximately 2%. In other words, Iranian political professionals of various political orientations lack the capacity and acceptance to represent the nation's political attitudes and demands. Iranian Instagram users have increased pressure on other popular Iranian Instagram pages, requesting that they reflect and even represent the political protests of the Iranian people. As previously explained, education, business, lifestyle, and fashion and beauty pages have not directly engaged with this demand of users due to professional considerations; however, a substantial portion of the movie, sports, and music pages have responded positively to the demand of their followers, largely due to their professional considerations. In actuality, it is the crisis of political representation that has placed celebrities in the position of representing the political demands of the Iranian people and given rise to the phenomenon of "celebrity-activists.”

In this sense, these are the people who have agency and have utilised the smallest opportunities to protest the status quo. In this way, they also take advantage of the opportunities provided by celebrities. In such a scenario, political professionals dissatisfied with the formation of these relationships between users and celebrities alter the truth and promote the narrative that "these excited people" have been duped by "illiterate celebrities!" Almost every political faction has employed such insults on occasion. Of course, these same "illiterate celebrities,” once defended participating in elections and voting for reformists, thereby increasing voter turnout. But, at the current time when celebrities are under the pressure of users and the online space has aligned with the Mahsa movement, conservatives and a significant portion of reformers assert that "the excited people" have been duped by the celebrities they follow. In actuality, instead of taking fundamental and principled measures to address the escalating crisis of political representation, political professionals sometimes align themselves with "concerned artists and athletes" and "intelligent people" and sometimes curse "illiterate celebrities" and "excited people" in accordance with their immediate interests.

Table 2: The rise in followers of popular Iranian Instagram pages by political orientation from 2019 to 2022

The relationship between Instagram users and popular pages has gradually developed an inherent logic over time, which can be made more tangible by examining a few examples from Table 3. Hassan Reyvandi's number of followers increased by more than 6 million between 2019 and 2020, when, in addition to political protest, the production of humour and entertainment content independent of official media was considered a high-demand commodity on Instagram. Consequently, he moved from third place in 2019 to first place in 2020. From 2020 to 2021, when humorous content independent of the official media still had some appeal, Reyvandi maintained his position by keeping a considerable distance from other prominent pages. Nonetheless, Reyvandi's position has been weakened over the past year, when "opposition to the existing political conditions" became the high-demand commodity on Iranian Instagram. Indeed, it is highly probable that he will soon be demoted. Rambod Javan has already experienced this fall. After failing to meet the expectations of political dissidents on Instagram, he dropped from the second most popular Iranian Instagram page in 2018 to the tenth most popular in 2019. Behnoosh Bakhtiari's position declined even further. Bakhtiari, who had the fourth most popular Iranian Instagram page in 2019, was harshly criticised by many Instagram users after taking several controversial positions, including publishing an Instagram post against the three protesters of November 2019 who were sentenced to execution. As a result, her page fell from the fourth most popular Iranian Instagram page to the nineteenth position within three years. Such evidence demonstrates that, contrary to the misleading term "influencer,” the resultant of the collective will of users has a substantially more direct and significant effect on the behaviour of influencers, not the reverse.

Table 3: Follower counts of the most popular Iranian pages from 2019 to 2022, per million users

From 2019 to 2021, the percentage of female Instagram celebrities in Iran rose from 32% to 42%. However, there has been no discernible change in the gender distribution of famous people over the past year. Likewise, while the percentage of popular pages based in Iran increased from 76% to 81% between 2019 and 2021, there has been no significant change in this regard over the past year.

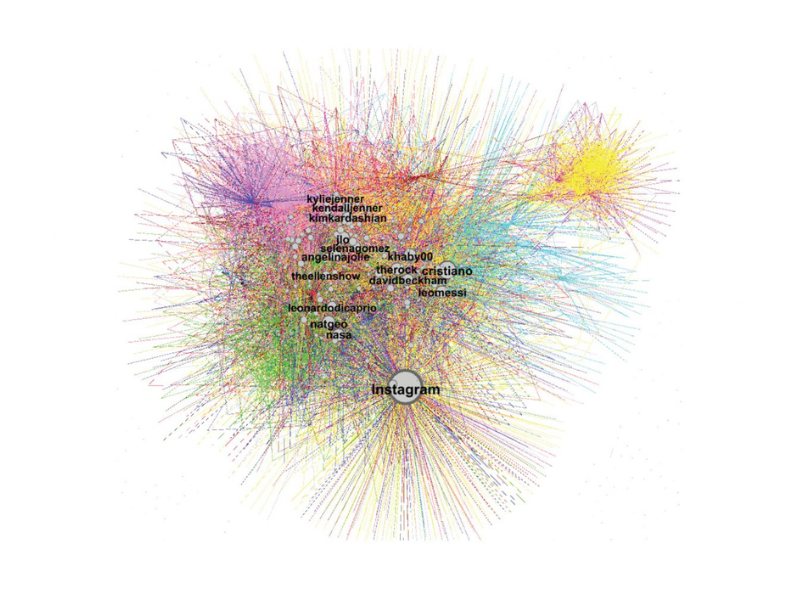

Let us conclude by examining the influence network of popular Iranian pages as affected by global authority pages. Based on the Authority Index, none of the foreign pages with high authority among the most popular Iranian Instagram pages are political. NASA, National Geographic, Leonardo DiCaprio, and Ellen DeGeneres have the most authority among film-oriented pages. Kylie Jenner, Kendall Jenner, and Kim Kardashian have the strongest authority among fashion and beauty pages. Jennifer Lopez, Selena Gomez, and Angelina Jolie have the highest authority jointly among the cinema and fashion and beauty pages. Moreover, Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo have the greatest authority among sports pages, while Khaby Lame, Dwayne Douglas Johnson, David Beckham, and the official Instagram page are authoritative among various sections of popular Iranian Instagram pages.

Figure 4: The position of authoritative international pages among popular Iranian pages on Instagram based on the Authority Index

Today, and particularly in the post-Mahsa era, the events that occur within the framework of online social networks are increasingly scrutinised by various political currents. Analysts with differing political leanings are discussing the relationship between online social networks and the collective protest actions of the Iranian people more than ever before. However, a quantitative increase in the analysis of online social networks can be considered a positive event if these analyses are continuously reviewed in conjunction with research findings in this field. Otherwise, it will not only be unenlightening but will also lead to the propagation of false stereotypes and, as a result, incorrect decisions and policies regarding this relatively new phenomenon.

Users' actions on online social networks may be correct in some cases but incorrect in others. It is crucial that whenever we find the actions of users to be inappropriate, we avoid blindly attributing everything to intelligent services, media, think tanks, or opportunistic and deceitful people. Instead of believing in these conspiracy theories, we should seek a more accurate understanding of the logic behind their actions and decisions using different methods and the logic of the situation in which users find themselves.

This methodological and analytic error is not unique to supporters of the government but is frequently committed by pro-change political currents when they encounter unpleasant phenomena in online social networks. In recent years, as a result of such a circumstance, many activists, analysts, and even some sociologists have shifted their focus from the lower levels of politics to security issues and have become experts on security issues and whistleblowers of media conspiracies and enemy think tanks.

The narrative of "excited and gullible users" is one of the recurring stereotypes regarding online social networks. In this narrative, social network users are uneducated and naive individuals who are constantly exploited by deceptive and opportunistic individuals, groups, and organisations. Throughout the past few years, and especially in the last few months, a great deal of commentary on Iranian Instagram has been based on this narrative. Interestingly, proponents of this narrative rarely question the veracity of this view and appear to see no need for scientific evidence to verify its veracity.

The results of the fourth phase of the longitudinal research I have conducted on Iranian Instagram users demonstrate conclusively that this narrative is highly misleading. Indeed, when criticising a false stereotype, we must take care not to fall into another false stereotype. Consequently, I hope that the caution that I have attempted to observe in writing this research report will be noted by the readers and that the research findings will be interpreted with the same caution.

Photo: IRNA

Regional Economic Integration Comes into Focus at Second Baghdad Conference

At the second meeting of the Baghdad Conference on Cooperation and Partnership, regional economic integration was a new focus for the countries involved.

The second meeting of the Baghdad Conference on Cooperation and Partnership took place in Amman, Jordan on December 20. Last year’s meeting in Baghdad initiated a process for multilateralism, dialogue, and cooperation between Iraq and its neighbours, some of whom met for the first time in years. This year’s gathering in Amman cemented the initiative as an annual regional summit and, importantly, added economic integration to the regional agenda.

In August 2021, former Iraqi prime minister, Mustafa Al-Kadhimi, with the support of French president Emmanuel Macron, managed to bring together officials from Egypt, Iran, Jordan, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates, as well as representatives from the European Union, Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), Arab League, Organisation of Islamic Countries, and the United Nations. This year, in addition to all those who participated in the first conference, the two missing GCC states—Oman and Bahrain—were present as well.

Al-Kadhimi largely succeeded by focusing on foreign policy, particularly as he sought to ease regional tensions. He was instrumental in revitalising relations with Iraq’s neighbours, which had been strained for years. He was also key in kickstarting dialogue between Iran and Saudi Arabia, as well as setting the stage for Iran-Egypt and Iran-Jordan talks. His hosting of the first Baghdad Conference positioned him—and by extension Iraq—as a trusted regional intermediary.

That is why Iraq’s recent transition to a new government was initially met with concern around the region. Mohamed Shia Al-Sudani’s seemingly pro-Iran stance was expected to once again strain Iraq’s ties with its Arab neighbours. There were reports that Saudi Arabia paused negotiations with Iran because of this change of government in Baghdad. But Al-Sudani’s efforts to retain the mantle passed by Al-Kadhimi put regional leaders at ease. He has committed to continuing his predecessor’s efforts to secure regional and international support for the development of Iraq—Baghdad remains in the title of the conference for this reason.

At the conference, Al-Sudani said, “The priority now lies in strengthening the bonds of cooperation and partnership between our countries through interdependence in infrastructure, economic integration and joint investments.” To that end, he argued that regional states should “strive to work together to transform from consuming to manufacturing countries by establishing joint industrial zones that enhance our collective industrial capacity and link the supply chains to one integrated chain capable of competing in global markets and launching mega projects in various sectors.”

By focusing on economic opportunities, Al-Sudani connected the Baghdad Conference to a wider agenda. He was also making an appeal for support from partners beyond the region, such as the European Union. EU High Representative Josep Borrell was present at the gathering in Amman.

In the Joint Communication on a “Strategic Partnership with the Gulf,” which was published in May 2022, the European Union praised the first Baghdad Conference and committed to supporting the region-led process. While France was the only European country supporting the Iraqi initiative initially, the European Union called for a follow-up process to the Baghdad Conference “with EU involvement” and as part of “a structured, EU-facilitated dialogue process”.

In the face of rising competition with other external players, such as China, Russia, and even India and Japan, European countries and the EU are falling behind. But Europeans can make significant contributions towards regional dialogue on economic integration by helping to create multilateral platforms, transfer know-how and technology, and provide financial support. European expertise can help the region find ways to jointly tackle the basic issues that have impeded economic growth and have resulted in spillover effects, such as increased food insecurity and inability to mitigate the rising challenges of climate change.

Establishing a new development fund by using existing instruments and institutions is key. This would mean including sovereign wealth funds, co-investment programmes, economic zones, or multi-party investment initiatives through regional banks or multinational institutions. The Islamic Development Bank, the various state-owned sovereign wealth funds within the GCC, as well as the European Investment Bank, and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, have all supported projects that have a multilateral or regional outlook. This could happen through matching funds allocated to the initiative by involved parties.

Through its Global Gateway project, the EU and regional partners could also “explore joint initiatives in third countries through triangular cooperation, financial support, capacity building and technical assistance.” The EU can draw in the regional players to help with reconstruction efforts in Iraq. The Global Europe Instrument foresees projects and investments in Iraq as well. The Instrument aims to fund international cooperation through grants, technical assistance, financial instruments, and budgetary guarantees.

Cooperation in developing a particular port or completing segments of Iraq’s national railway should be the priority. Exploring joint investments in Iraq’s oil and gas industry as well as green energy transition should also be considered.

Dust and sandstorms, as well as drought and water scarcity, are causing huge financial and human costs for Iraq, but also for all neighbouring countries, as well. Key projects that combat shared environmental challenges, which have proven to be the easiest avenue for cooperation, should be explored.

Even though various regional tensions remain, the outlook for regional cooperation and multilateralism seems bright and the Baghdad Conference is helping define a framework for broader regional cooperation, with integration as its aim. As Dutch diplomat Jeanine Hennis-Plasschaert, Special Representative of the Secretary-General for the United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq, reflected during the meeting, the “demonstration of regional partnership” can now “result in a number of concrete steps.” Hennis-Plasschaert added that these steps “might even lead to a framework for regional integration as an effective means of achieving prosperity, peace and security.”

Photo: King Abdullah Press Office

When it Comes to Iran, China is Shifting the Balance

Xi Jinping’s recent trip to Riyadh, his first foreign visit to the Middle East since the pandemic, suggests that China may no longer seek to treat Iran and its Arab neighbours as equals.

In 2016, during his first trip to the Middle East, Chinese Premier Xi Jinping visited both Riyadh and Tehran, a reflection of China’s effort to balance relations among the regional powers of the Persian Gulf. But Xi’s recent trip to Riyadh, his first visit to the Middle East since the pandemic, suggests that China is no longer aiming to treat Iran and its Arab neighbours as equals.

Following the meetings in Riyadh, China and the GCC issued a joint statement. Four of the eighteen points that comprise the joint statement directly pertain to Iran. In the declaration, China and the GCC countries called on Iran to cooperate with the International Atomic Energy Agency as part of its obligations under the beleaguered Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Using strong and direct language, the statement additionally called for a comprehensive dialogue involving regional countries to address Iran’s nuclear programme and Iran’s malign activities in the region. The language used was less neutral than that typically seen in Chinese communiqués and instead took the tone of Saudi and Emirati talking points regarding Iran.

Iranian officials were especially vexed to see that China had effectively endorsed longstanding Emirati claims to three islands: Greater Tunb, Lesser Tunb, and Abu Musa. The islands, located in the Strait of Hormuz, were occupied by the Imperial Iranian Navy in 1971 after the withdrawal of British forces. Ever since, Iran has considered the three islands as part of its territory. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) has made periodic attempts over the last four decades to regain control of the islands, claiming that before the British withdrawal, the territories were administered by the Emirate of Sharjah. While the statement does not go so far as to declare that the islands belong the UAE, China’s call for negotiations over their status inherently undermines Iran’s claims.

The reaction of Iranian officials and the public has been sharp. The day after the statement was published, Iranian newspapers featured bitter headlines. One newspaper even provocatively questioned China’s claim over Taiwan. Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian tweeted that the three Persian Gulf islands belong to Iran and demanded respect for Iran’s territorial integrity. Meanwhile, Iran’s Assistant Foreign Minister for Asia and the Pacific met with the Chinese Ambassador to Iran, Chang Hua, to express “strong dissatisfaction” with the outcome of the China-GCC summit.

Amid the polemic generated by the China-GCC statement, the Chinese official news agency Xinhua announced that Vice Premier Hu Chunhua would visit Iran and the UAE next week. If the stopover in Tehran was intended as a Chinese gesture to ease tensions, the move is likely to backfire. While “Little Hu” had been expected to gain a prestigious seat in the Politburo Standing Committee during the recent National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), he was instead demoted from the Politburo and is expected to be removed as Vice Premier in March 2023. Considering Xi’s triumphal visit to Riyadh, the optics surrounding Hu’s planned visit to Tehran are especially bad.

As Xi begins his third term as China’s leader, he appears to be viewing relations with Iran through the prism of liability, rather than opportunity. Despite the fanfare surrounding the beginning of Iran’s long-awaited accession to the China-led Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) in September, this was a relatively shallow political move. The SCO is an organisation with a limited institutional capacity and substantial internal divisions—Iran’s accession did not herald the opening of a new era in Sino-Iranian relations.

Two issues appear to be hampering China-Iran relations. First, negotiations to restore the JCPOA have failed. With sanctions in place, Iran has struggled to attract Chinese investment and cooperation, especially when compared to Saudi Arabia and the UAE. As I argued in March, economic ties are a pillar of the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (CSP) that China and Iran have devised, but relaunching economic relations between the two countries requires successful nuclear diplomacy and the lifting of US secondary sanctions. Beijing and Tehran announced the beginning of the CSP implementation phase last January when the nuclear talks appeared likely to succeed. Today, the prospects for implementing the CSP are nill and China-Iran trade is continuing to languish at around $1 billion in total value per month.

Second, Iran’s decision to sell military drones to Russia, thereby becoming actively involved in the war in Ukraine, is proving a significant strategic miscalculation. By actively supporting Russia’s war of aggression, Iran has taken itself out of a large bloc of countries, nominally led by China, that have adopted an ambiguous position towards the conflict. This bloc, which notably includes the GCC countries, is neither aligned with Ukraine and NATO nor openly against Russia and its coalition of hardliner states. In short, Iran’s overt alignment with Russia is at odds with China’s approach.

Meanwhile, the evident strains in US relations with Saudi Arabia and the UAE have created an opening for China to deepen ties with the two regional powers. In some respects, this opening has diminished China’s need to cultivate a deeper partnership with Iran. Ties with Tehran had long been attractive as a means to counterbalance US influence in the region. But Beijing’s success in building deeper relations with Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, two capitals that have long taken their cues from Washington, suggests that China is gaining new means to check US power in the Middle East.

China-Iran relations have seesawed plenty over the years, but the outcome of Xi’s visit to Saudi Arabia suggests a new and more negative outlook for bilateral ties. While Iran tries in vain to “turn East,” China may be shifting away.

Photo: IRNA

Participatory Budgeting Opens Path for Democratic Reform in Uzbekistan

A participatory budgeting initiative may prove a vital step forward in Uzbekistan’s political development if it opens the path to wider democratic reforms.

Since his inauguration in 2016, President Shavkat Mirziyoyev has paved the way for many policy reforms in Uzbekistan. Four of these reforms stand out as truly consequential.

The first two reforms are economic. The move to a mostly market-based foreign currency regime and the implementation of tax reforms delivered significant positive stimuli for economic growth and helped to open the Uzbek economy to foreign investment.

The third reform put an end to the abhorrent practice of state-sponsored forced and child labor. Possibly more than any other, this reform has earned Uzbekistan international praise. The Economist named Uzbekistan “country of the year” in 2019, describing it as a country “that abolished slavery.” Although labour rights and state intervention issues persist in cotton production clusters, the reform effort still successfully stigmatised forced labor among top officials, improved many labour conditions, and opened the Uzbek cotton and textile industry to international trade.

The fourth reform has garnered less international attention but is no less significant. The Citizens’ Initiative Budget is a participatory budgeting platform that lets the public decide where they think it is best to spend public money. The policy aims at better redistribution through decentralization of budget planning.

The initial outcomes are exciting: 7.8 million votes were cast in support of 61,500 spending projects in 2022. The votes determined the allocation of USD 100 million across 98 percent of all micro-districts (mahallas) in Uzbekistan. Compare this to 2021, when 6.72 million votes were collected on 69,700 projects. This year voter turnout increased, while the collective action improved with fewer—and likely more realistic—nominated projects. It is estimated that 33 percent of Uzbek adults participated in the voting process in 2022. A prominent blogger suggested that the participatory budgeting process was the country’s most competitive election. While tongue in cheek, this reaction to participatory budgeting points to its significance—people mobilise and vote for the option that best represents their needs.

Without true electoral accountability in the country, Uzbekistan’s central government often receives distorted signals from its people. That is why reforms that leverage the tools of participatory democracy are so crucial. Arguably the most significant recent example of distorted signals was when in July of this year Karakalpakstan’s legislature and government unanimously supported the constitutional amendments to dissolve its semi-autonomous status. Mass civil unrest erupted leading to deaths, injuries, and property damage. President Mirziyoyev later berated the Karakalpak lawmakers for failing to communicate the people’s concerns and wishes to the central government.

Alongside the participatory budget, another valuable source of signals is Uzbekistan’s media environment, which has become more free since 2016 as outspoken bloggers and probing journalists write for a range of independent digital media outlets. Even though the state-owned national television, radio, and print media have little impact on policymaking and there remains censorship, the Presidential Administration now regularly cites Telegram messages and local reports when demoting bureaucrats and municipality heads—a sign that the media is supporting accountability. Investigative reporting also sometimes forces municipal or regional authorities to abandon or adjust unpopular decisions before public anger escalates.

As promising such anecdotal occurrences of accountability may be, they do not and cannot accurately represent or equitably empower all the people of Uzbekistan. For one, there is a clear digital divide in how many people own smartphones and can afford or access the internet. Richer urban areas with better education, more infrastructure, higher incomes, and more active civil society enjoy a greater capacity to mobilise and take advantage of initiatives like participatory budgeting. These divides can be self-reinforcing. Therefore, as a rule, central governments try to keep urban residents more content.

Another reality is that such feedback channels mostly enable short term policy interventions, and do not necessarily help in gauging long term sustainable development priorities and population needs. While participatory approaches and media attention can help citizens respond when, for example, a green space is endangered, other important decisions about where to build roads and schools or when hire doctors and buy vaccines have much steeper collective action costs. Without regular bottom-up elections, in which politicians are asked to define their policy agendas and are held accountable to those agendas, it is difficult to collect informational signals on what the population wants even if everyone agrees on the essentials.

The Citizens’ Initiative Budget may prove a vital step forward in Uzbekistan’s political development if it opens the path to wider democratic reforms. Such reforms may be necessary if Uzbekistan wants to build on five years of strong economic growth—social scientists agree that the quality of political institutions determines economic outcomes.

Encouragingly, Uzbekistan is set to substantially expand its participatory budgeting platform. In 2022, the government will increase funding to nearly USD 250 million and has pledged at least USD 700 million to be disbursed in 2023. Moreover, the government has proposed that all infrastructure projects in micro-districts will be funded through participatory budgeting. A recently circulated draft white paper from the Presidential Administration suggests granting 28 districts expanded local governance authority, giving local legislators full-time paid employment, and empowering local residents with the ability to recall underperforming lawmakers and officials.

Ultimately, the essential condition for good governance at any level is enabling free and fair elections. Free and fair elections will optimise distribution of economic resources, enable growth, reduce corruption, and advance inclusion and happiness. As the success of the Citizens’ Initiative Budget shows, the Uzbek people are ready to take charge of their shared political future.

Photo: AXP Photography

Long-Awaited Uzbek-Kyrgyz Border Deal Sparks Unrest

The final demarcation of the Uzbek-Kyrgyz border was expected to be a tremendous political victory for Kyrgyzstan. But instead of celebration, the agreement has spurred domestic unrest and intensified repression.

In October, the final demarcation of the Uzbek-Kyrgyz border was expected to be successfully concluded after three decades of negotiations. The agreement was supposed to be a tremendous political victory for Kyrgyzstan, especially for President Sadyr Japarov. But instead of celebration, the agreement has spurred domestic unrest and intensified repression.

Most visibly, the unrest is due to the Kempir-Abad water reservoir in the Uzgen district. The local population in Uzgen believes that the government and president’s close ally Kamchybek Tashiev's negotiating team failed to fully address state borders, land ownership, and water management in the area and did not adequately explain the deal to the public. Concerns about ceding the important reservoir to another country and abandoning Kyrgyz land were frequently voiced, but the government downplayed concerns. Some members of a parliamentary committee responsible for the preliminary approval of the new border also complained about the secrecy of the agreement. The exact full wording of the deal was not published, which led to uncertainty about what they were actually voting for, and some parliamentarians refused to vote at all.

Japarov faced opposition to the announced border agreement both in media and in the streets. On October 22, a committee for the protection of Kempir-Abad reservoir was formed. Activists also organised a demonstration denouncing the deal and demanding transparent public discussions. However, Japarov labeled the protests as the product of the "evil intentions” of a few opponents.

To succeed, the regime has resorted to silencing the opposition voices until the deal is officially signed. On October 23, there was a mass detention of two dozen vocal opposition activists in Bishkek and elsewhere around the country. The Kyrgyz government also decided to take action against the local operations of Radio Free Europe and blocked the broadcaster’s website for two months over the alleged spreading of disinformation. Later, the National Security Committee—headed by Tashiev—ordered Demir Bank to close RFE’s local account.

The crisis over Kempir-Abad and the entire border demarcation process illustrates one of the core problems of the current Kyrgyz government: an authoritarian approach to sensitive domestic issues. On the agreement with Uzbekistan, Japarov and Tashiev decided to push the deal through the opposition using their political influence and power. There is no exact date of the official signature announced, and under the current circumstances, neither the official implementation nor peaceful acceptance of the deal by the Kyrgyz society is certain.

Since his ascendence to power after large public protests in October 2020, Japarov has relied on his image as a strong national leader. Issues regarding territory, national interests, mineral resources, and economic prosperity have formed the core aspects of his political agenda. In recent months, however, he has faced mounting challenges in every domain. Moreover, attempts by Kyrgyzstan to present a border agreement regarding Kempir-Abad failed last year. Experiencing the same failure again would be a huge blow to Japarov’s political career.

Aside from its border issues with Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan also lacks fully demarcated borders with Tajikistan. Various factors have delayed the demarcation process since the dissolution of the former Soviet Union. These include complicated physical geography, mixed ethnic populations, and domestic political stakes. Tensions between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have been rising in the past few years and there is little hope that the situation will improve in the foreseeable future.

The government’s nationalist rhetoric has not helped. This rhetoric has been accompanied by armed clashes and unprecedented levels of violence earlier this year. Neither Bishkek nor Dushanbe are interested in launching a full-scale war against one another, and destabilisation of the wider region is against the interests of their neighbours too. Even so, neither side has shown the willingness to engage in negotiations. For the time being, leaders in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are using to justify consolidation of power at home.

While condemnable, Japarov and Tashiev’s attempts to secure the regime's position by silencing critics are hardly surprising. But the scale of the repression is concerning. Despite domestic turmoil, Kyrgyzstan still enjoys a reputation as a country with a more vibrant civil society and greater democratic mechanisms than its neighbours in Central Asia. However, researchers, activists, and civil society members interviewed by the author in recent months unanimously pointed to a worsening outlook and cited the disappearance of previously understood “red lines” and the unpredictability of authorities’ punitive actions.

Tashiev’s participation at a meeting with Vladimir Putin in Moscow last week under the auspices of the Commonwealth of Independent States illustrates Kyrgyzstan's slide towards more oppression. During the meeting in Moscow, non-governmental organisations and international bodies were labeled as threats and destructive forces.

The unrest and regime instability in Kyrgyzstan may have a negative impact also on other international projects, including the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbek railway, which has been on the table for two decades with no traction until last month when it was finally put forward. If the unrest persists, the parties to the rail deal may run out of patience. Moreover, Uzbekistan may either delay the ratification of the border agreement or demand more favourable conditions at Bishkek’s expense.

But even if the border deal materialises and both Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan implement the agreement, issues on the ground will likely persist. The newly demarcated border requires effective border management, trust, and mutual endorsement by the locals on both sides. Without a proper arrangement, even a minor skirmish might escalate to a major border conflict. Moreover, the contested future of the Kempir-Abad water reservoir further adds to the complexity to an already fragile situation at the Kyrgyz-Uzbek border.

Photo: Press Service of the President of Uzbekistan

As Protests Continue, Biden Should Enable Remittance Transfers to Iran

The Biden administration should adjust its sanctions policies to authorise remittance transfers to Iran, making it possible for Iranians in the diaspora to support their family members in ways that strengthen capacities for political participation.

Protests in Iran are continuing as the Iranian people bravely maintain a presence in the streets and on social media. So far, Iranian authorities have given no clear indication that they will reform policies in line with protest demands and have signalled that a larger crackdown may be coming.

While the protests have meaningfully shifted the political discourse around women’s rights and state repression, it is unclear whether Iran’s civil society has the resources necessary to generate a large and lasting protest movement that maintains pressure on Iranian authorities and raises the costs of further crackdowns. One critical factor is the economic disempowerment of Iranian society over the last decade.

Between 2010 and 2020, the spending power of the average Iranian household has fallen by just over 20%. This loss of economic welfare is primarily the result of U.S. sanctions, particularly those imposed in 2012 and re-imposed in 2018. In the two decades leading up to 2012, Iranian households enjoyed an unbroken period in which living standards were rising.

U.S. sanctions policy has made protests in Iran more frequent, but also less likely to succeed. The economic precarity that has become a dominant feature of the Iranian social condition over the last decade makes it harder to sustain protest movements. Many Iranians literally cannot afford to organise and mobilise over weeks and months. Workers are reluctant to strike given the risk of losing their jobs. Even those who retain the economic means to protest lack the tools to organise.

In institutional terms, sanctions have weakened the formal and informal civil society organisations that help mobilise the middle class and channel middle class resources towards political action. Charities, advocacy groups, legal aid providers are starved of resources. Civic-minded women, who are at the forefront of Iran’s new protest movement, have been hit especially hard. As one Iranian activist put it last year, “Activists are struggling to survive… If they do end up with a bit of time at the end of the day for their activism, they are often too exhausted and preoccupied with economic survival to be effective.”

The recent protests have no doubt energised a wide range of social groups in Iran, but looking in both economic and institutional terms, the balance of power between Iranian state and Iranian society has clearly shifted in the state’s favour. Mobilisations have become more frequent, but they tend to be smaller and more fleeting, making it easier for the state to either crackdown or to simply wait out the protests.

As such, the Biden administration should adjust its sanctions policies to broadly authorise remittance transfers to Iran, making it possible for Iranians in the diaspora to support family and friends in ways that reduced economic hardship and strengthen capacities for political participation.

Remittance flows are restricted because banks and money transfer companies do not facilitate transfers to Iran owing to sanctions on the Iranian financial system. Most remittances are therefore made via exchange bureaus (known to Iranians as sarafis) or are hand-carried into Iran by individuals. U.S. persons are explicitly authorised to hand-carry personal remittances but are not permitted to use money service businesses. The financial flows made through exchange bureaus and hand-carry channels are difficult to track and so the true extent of remittance flows may not be reflected in authoritative estimates, but Iran is likely receiving far less remittance transfers than countries with similar economic characteristics.

The World Bank estimates Iran received $1.3 billion of remittances in 2021, equivalent to just one-tenth of a percent of GDP. By comparison, Thailand, a country with a higher per capita GDP ($19,000 vs. $16,000 in PPP terms) and a smaller population (70 million vs. 84 million), received $9.0 billion of remittances, equivalent to 1.8 percent of GDP.

It is unlikely that exchange bureaus and physical transfers total in the many billions of dollars. In short, Iran’s remittances inflows are much lower than expected given the size of the economy and the economic needs of the population. Remittances flows are far too limited to shore the economic welfare of households in the face of the generalised economic crisis to which sectoral sanctions contribute—a fact evidenced by the erosion of household consumption over the last decade.

A significant body of academic research suggests that remittances encourage political participation, including in protests. In a 2017 paper, Malcolm Easton and Gabriella Montinola use individual-level data from Latin America to explore the relationship between the receipt of remittances and political participation. They find that “remittance recipients are more likely to select protest rather than the base response” whether in a democracy or autocracy. Additionally, in autocracies, remittances make political change seem more achievable. Easton and Montinola explain that “receiving remittances increases the odds of selecting protest relative to believing change is not possible by 34%.” Abel Escriba-Folch, Covadonga Meseguer, and Joseph Wright arrive at a similar conclusion in their 2018 study which used individual-level data from eight African countries. They find strong evidence that “remittances increase protest by augmenting the resources available to political opponents” and “remittances may thus help advance political change.”

The Iranian diaspora in the United States is the largest and most politically active in the world. As U.S. persons, members of the diaspora living in the United States are unable to send remittances to Iran beyond the hand-carry method, which is not an option for those who cannot travel to Iran for personal or political reasons, or who are opting not to travel to Iran due to the increased risks facing dual nationals. To provide routine and reliable financial support to family and friends in Iran, members of the Iranian diaspora should be able to avail themselves of money service businesses or other payments solutions.

The relevant regulation does stipulate that remittance transfers “processed by a United States depository institution or a United States registered broker or dealer in securities” are authorised. However, there is a lack of such institutions offering remittance services for Iran—U.S. banks do not maintain correspondent accounts at Iranian financial institutions. As such, the Biden administration should update its regulations to enable U.S. persons to make remittances transfers through other channels. This can be done through the issuance of a new general license with two aims.

First, the Biden administration could authorise the use by U.S. persons of money service businesses, such as Europe-based exchange bureaus, to transfer non-commercial, personal remittances to Iran. Second, and perhaps more usefully, the Biden administration could authorise the use by U.S. persons of cryptocurrency exchanges to purchase USDC stablecoins and transfer those stablecoins as non-commercial, personal remittances to Iran. The administration would also need to authorise U.S. cryptocurrency exchanges to onboard users in Iran.

Exchange bureaus can typically make deposits to accounts at Iranian financial institutions. The existing regulations do state that U.S. banks can engage with money service businesses in third-countries to make remittance transfers to Iran. But that makes such transfers subject to the discretion of U.S. banks. The guidance should be modified such that U.S. persons can directly engage exchange bureaus, for example those in Europe, to make transfers to Iranian bank accounts. Making it possible for U.S. persons to use third-country money service businesses would have an immediate impact on the volume of remittances sent to Iran. However, this channel cannot scale indefinitely as money service businesses generally need to balance inflows and outflows to make transfers in a netting process.

The use of cryptocurrency could be even more impactful. While few Iranians maintain cryptocurrency accounts, the technology provides one of the few scalable options for enabling U.S. persons to make remittance transfers to Iran. So long as cryptocurrency exchanges receive guidance that allows them to onboard Iranian users, Iranians can be expected to adopt the technology and U.S. persons will be able to transfer cryptocurrency without a constraint on scale.

The authorisation should be limited to exchanges and should not cover transfers made directly to addresses or via wallet providers, because of the additional controls that the exchange can impose. It is technically feasible for cryptocurrency exchanges (such as Coinbase and FTX) to limit the value of transfers that can be received and held by Iranian users in line with the provisions of the authorisation. Additionally, transactions processed by the exchange do not happen on cryptocurrency blockchains, they are run within the exchange’s internal database. This enables the exchange to freeze any account held by its user and block further transfers if necessary. Moreover, the exchange could ensure that users were only able to transfer certain cryptocurrencies to Iran, such as traceable USD stablecoins which are pegged to the dollar (the best option is USDC, which has a track record of cooperation with US regulators). This would ensure that exchanges are not providing a platform for speculative trading by Iranian users and that Iranians do not have a perverse incentive to hold onto their remittances. These exchanges can also require additional KYC for U.S. persons and Iranian individuals on either end of a given transfer.

To be effective, these authorisations would need to be followed by extensive outreach by the U.S. Department of Treasury and U.S. Department of State to ensure that money service businesses and cryptocurrency exchanges begin supporting Iran-related transfers. U.S. authorities would also impress the importance of monitoring for suspicious transactions and could ask for data on the remittance flows to enable better enforcement. Any authorisation could be granted based on a limit to the value of remittances made by a U.S. person each month—a limit as low as a few hundred U.S. dollars could make a significant difference in supporting basic household welfare in Iran.

There is a risk of abuse by individuals seeking to transfer funds to designated entities or individuals in Iran. But the risk is limited. Flows of USDC cannot be directly taxed or expropriated by the state. To spend any remittances they have received, Iranians would either need to pay for goods and services by transferring USDC to another Iranian user that has created an account on the exchange, or by finding an Iranian user who is willing to exchange USDC for cash.

The lack of hard currency flows means that the proposed action does not entail a substantive change to the structure of U.S. sanctions on Iranian economic sectors and state-owned and controlled entities. Even so, the authorisations can significantly boost the economic resources of Iranian civil society and enable more robust political participation, including in protests. However, the decision to participate in the protests lies with each Iranian. Unlike a strike fund, this policy does not create an incentive for protest, nor are the remittances made contingent on certain kinds of political action.

There is a precedent for this approach. Even while adding sanctions on the Maduro government, the Trump and Biden administrations have notably allowed Venezuelans to continue to use U.S.-based financial services, such as the payments app Zelle, to send and receive U.S. dollars. This has had the effect of shielding many Venezuelans from even steeper declines in economic welfare as the country experienced a steep sanctions-induced recession.

Enabling Iranian-Americans to make remittance transfers to their family members in Iran within the context of existing sanctions regulations would mean that the Biden administration is not only seeking to deprive the Iranian state of resources for repression but is also working actively to preserve the power of the civil society at a time of general economic crisis. This is what true solidarity would look like.

Photo: IRNA

Iranian Women are Colliding with the Iranian State

Iranian women, supported by the many men who have now joined them, are challenging the discrimination they have experienced for decades.

On the day that Ebrahim Raisi, Iran’s President, was giving a speech at the United Nations headquarters in New York about the double standards with which human rights are pursued around the world, a tear gas canister flew past me and hit a car that was parked a few metres away. I was among the protesters running down Palestine Street in the centre of Tehran, and the tear gas was being fired directly at us by anti-riot police. We were doing nothing more than shouting slogans, but any of us could have been severely injured or killed—this was not an isolated incident. According to human rights groups, more than 90 people have been killed in the ongoing protests across Iran. The protests were ignited by the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini while she was in the custody of the morality police. The authorities have responded to these protests with a brutal crackdown—beating, shooting, arresting—and an internet blackout that has blocked access to platforms such as WhatsApp and Instagram.

Twenty years ago, it would have been hard to imagine that dozens of cities in Iran would erupt in protests against imposed religious rules. The death of Zahara Bani Yaghuob, an Iranian medical doctor arrested by authorities in Hamedan in 2007, did not lead to widespread protests at the time. But the Iranian state is reaping what they have unintentionally sown. Despite rolling back some women’s rights, such as the Family Protection Law introduced under Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, and imposing an Islamic dress code, after the revolution, a so-called Islamic educational system helped more women in rural and lower social classes to receive an education. While women in upper and middle social classes benefited from progressive laws prior to the revolution, traditional families, typically from disadvantaged backgrounds, felt more comfortable sending their daughters to school under Islamic laws. Today, women account for 60 percent of university students in Iran. It is no coincidence that Generation Z, now on the frontlines of the recent protests, are the children of Iran’s 1980s baby boomers. Generation Z’s parents were the first cohort to see a dramatic shift in the numbers of women receiving higher education in Iran.

A few hours before the tear gas canister nearly struck me on Palestine Street, I was passing security forces on Revolution Avenue when a man in plain clothes and a helmet came up to me and said, “Our cameras will capture your face. If I see you again in this area, you’ll get arrested.” “For what crime?” I asked. “No offence required,” he replied, “I have the power, and I’ll use it against you.”

The man’s boast is the key to understanding the recent protests in Iran. After Sepideh Rashnoo was harassed on a bus by a fellow citizen over her “improper” hijab in July, the dangerous power that had been delegated to pro-regime citizens became clearer. Iranians watched Rashnoo, a writer and artist, make a humiliating forced “confession” on national TV. In contrast to Rashnoo’s humiliation, the woman who harassed her over her hijab enjoyed a kind of authority bestowed upon her by the government.

Along with the morality police, the citizens who have been granted this authority stepped up their policing of the hijab rules since Raisi’s election, which was marred by record low turnout. The death of Mahsa Amini while in police custody has revealed the conflict between the Iranian government and citizens who do not want to comply with rules they believe infringe on their civil rights. There is significant disillusionment and profound doubt about the prospects of reforming a system that has shown zero interest in compromise. If the Green Movement’s slogans were full of verses from Qur’an and other Islamic references, the slogans heard in the recent protests contain no Islamic references and no requests for narrow reforms.

Despite the economic stagnation, systematic corruption, and mismanagement in recent years, economic grievances do not feature in the slogans either. The protests have coalesced around dissatisfaction about how the Iranian state relates to society. The protests that erupted after Mahsa Amini’s death emerged mainly from marginalised groups: Kurds who are an ethnic minority, the middle class which as encountered so much hostility from the government, women who are not even recognised or protected in the system if not wearing a hijab, and the working class who have witnessed widespread governmental corruption in the recent years.

While living under the strict rules of an increasingly authoritarian state, the future for these oppressed groups is grim—they see a dead end. Accordingly, for the Iranian authorities, the unification of these various social groups, which has happened for the first time since the 1979 revolution, poses a new challenge.

In recent years, Iran’s middle class has been shrinking because of international sanctions and economic decline. Still, they have had some spaces, such as social media and satellite television, to engage with progressive ideas on human rights. Long before the recent protests forced Iran’s national television to address the issue of compulsory hijab on their programmes, subjects such as the hijab, personal freedom, and gender politics have been debated on social media and foreign-based television channels before large audiences. In this way, two different worlds have coexisted and one is now crashing into the other.

Are we witnessing another revolution in Iran? It is hard to ascertain. Iran’s state ideology still has sincere supporters, not just at home but also across the region. Some analysts have pointed to the limited number of protesters to suggest the protests are a “virtual revolution” that exists only on social media. Still, a revolutionary turn does not necessarily depend on the number of active protesters; it arises from a dead-end situation. Following Ayatollah Khamenei’s speech in which he called the protests “riots” and blamed a foreign plot for the unrest, the obstruction has never been clearer.

Nevertheless, there is a movement in Iran. Motivated by their anger following Mahsa Amini’s death, a growing number of women who have found the courage to go out with their hair uncovered in public. For a political system that places enormous emphasis on women’s appearance, this is a profound form of protest. Iranian women, supported by the many men who have now joined them, are challenging the discrimination they have experienced for decades. They have already achieved a great victory by making their voice heard around the world.

Photo: EPA-EFE

Can SCO Members Achieve Connectivity in the Face of Conflict?

If the SCO is to mature as an organisation and make good on its vision of connectivity, it must also serve as a platform for conflict resolution.

The two-day Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit took place last week in Samarkand, Uzbekistan. Aside from agreeing to the Samarkand Declaration, which summarises the intention of SCO members to foster deeper economic partnerships, the gathered leaders also signed 44 documents consisting of numerous memorandums, roadmaps, and action plans for cooperation in tourism, artificial intelligence, and energy.