To Break With Austerity, Rouhani Must Deliver on Sovereign Debt Sale

◢ To win foreign investment, Iran's needs to boost development expenditures. But expansionary fiscal policy will require a new source of revenue, as oil sales remain stagnant and tax rises remain politically risky.

◢ A sovereign debt sale, long discussed by Iranian officials, is the fundamental way Iran can find the revenues to self-fund growth. The Rouhani administration must focus on making its bond offering a reality.

One of the remarkable, and yet little discussed, aspects of the Iranian election is that Hassan Rouhani triumphed despite being an austerity candidate. His first term was notable for its frugal budgets and commitment to both slash government handouts and reduce expenditures in an effort to tackle inflation. On one hand, the focus on a more disciplined fiscal and monetary policy meant that Rouhani could point to a successful reduction of inflation from over 40% to around 10% while on the campaign trail. On the other hand, job creation has been stagnant and the average Iranian has seen little improvement in their economic well-being.

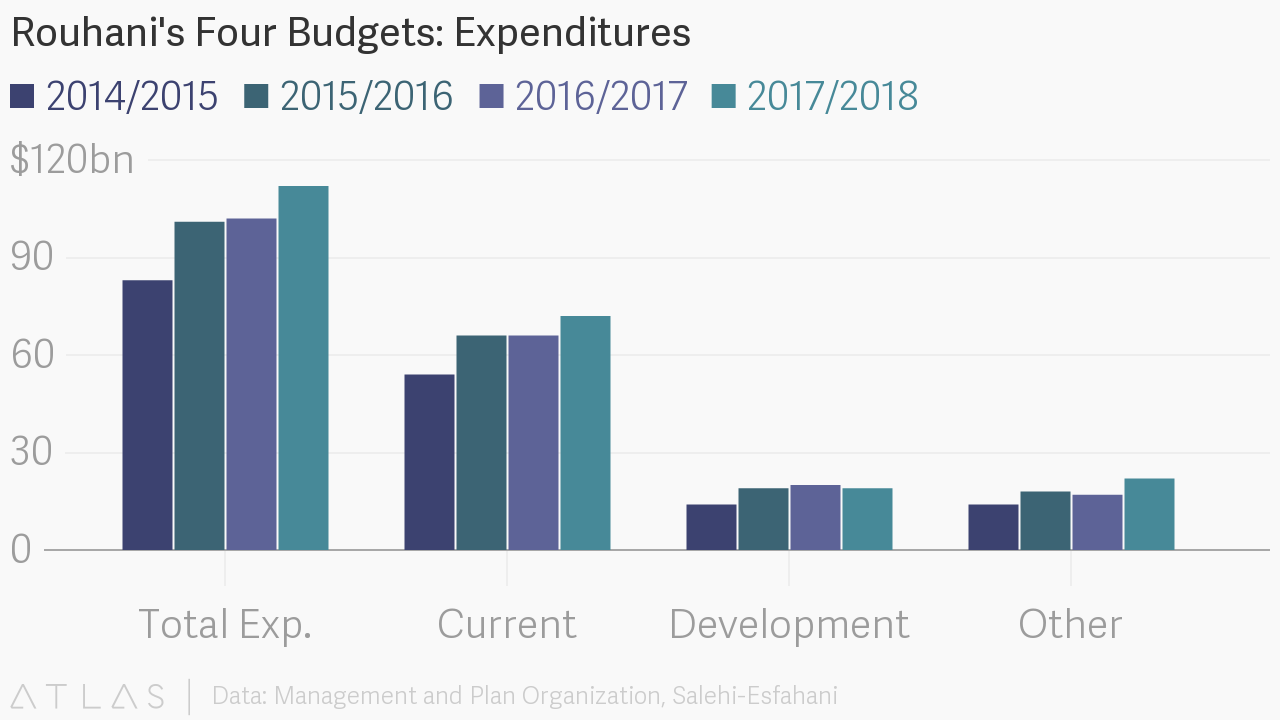

Some economists, including Djavad Salehi-Esfahani, have argued that Rouhani’s austerity economics are misguided, depriving the economy of vital liquidity that could help jumpstart investment and job creation. For example, Iran’s 2017/2018 budget sees tax revenues stay constant at an equivalent of USD 34 billion despite the fact that economic growth is expected to top 6%. Salehi-Esfahani believes that these figures reflect the Rouhani administration's belief “that letting the private sector off easy would encourage it to invest.” The government, meanwhile, will not contribute much more in investment. Development spending is set to decrease from USD 20 billion to USD 19 billion.

Surely, the Rouhani administration’s pursuit of a small government that leaves the burden of job creation and economic growth to the private sector is admirable. It represents a significant shift in the mentality that has characterized the economic policy of the Islamic Republic, which has long relied on state-owned enterprise and state-backed financing, supported by oil revenues, to drive economic growth.

But the volume of investment needed to revitalize economic sectors and create substantial job opportunity has not yet materialized. This is an undeniable fact, which Rouhani has attributed to failures on the part of Western powers to adequately implement sanctions relief, leaving international banks unable to work with Iran. Rouhani’s opponents meanwhile, attributed low volume of foreign direct investment to his administration's mismanagement. There is truth to both accounts.

In many ways, Rouhani’s lean towards austerity was a response to the spendthrift policies of his predecessor, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. The Ahmadinejad administration responded to faltering economic growth during a period of historic oil revenues by ploughing oil rents into the banking system and compelling banks to issue loans. These loans were often provided without the adequate due diligence and were used not to finance growth, but increasingly to fuel speculation, or more forgivably, to address cash flow difficulties faced by companies as a result of international sanctions.

As a result, Iran’s banking sector is now weighed down with a high proportion of non-performing loans, accounting for around 11% of total bank debt. When bank balance sheets grew increasingly precarious as non-payment of loans mounted in the sanctions period, competition for deposits grew. Exacerbating this competition, banks needed to provide higher deposits rates in order to stay ahead of inflation. The combination of forces pushed interest rates up to all-time highs.

The debt market in Iran is now broken. The IMF has urged urgent action to “restructure and recapitalize banks.” In the meantime, banks remain disinclined to lend and in the instances where healthier banks are able to provide loans, borrowers must contend with the high cost of debt.

This may help explain why the Rouhani administration so aggressively sought to address inflation—it was a necessary step to reduce the benchmark interest rate, which has so far been reduced from a high of 22% in 2014 to the current rate of 18%.

But even at such time that interest rates normalize, barriers will remain to the use of debt markets. At a structural level, Iranian companies, particularly in the private sector, rely on equity financing rather than debt financing in order to fund growth. This reflects a “bloc” behavior within Iranian enterprise. Partially as a consequence of the continued dominance of family-owned businesses in Iran’s non-state economy, business leaders tend to approach financiers within their own networks or holding groups, and many of Iran’s largest companies and banks anchor conglomerates that grew out of sequential processes of a kind of inward-looking venture capital. There is limited comfort among Iranian business leaders to seek funding from groups outside of these tight networks and by the same token, equity investors hesitate to provide finance projects outside their own networks. This means that the pool of available investor capital is rarely competing across the whole pool of available capital deployments—a significant inefficiency.

Growth-oriented investing itself can be a difficult strategic proposition. Iranian business leaders have understandably prioritized weathering periods of uncertainty over the execution of long-term plans. The challenge of dealing with short-term volatility has naturally favored short-term thinking. Major companies are only recently undertaking strategic reviews that might identify needs to invest in capital improvements or new services in order to drive growth in support of long-term goals.

The combination of the bloc effect in equity financing and the broken debt market creates a major brake on economic growth, especially from a supply-side perspective. To restore momentum, a third party is needed to order to reset the incentives and mechanisms around financing in Iran.

From the outset of its tenure, the Rouhani administration has hoped foreign investors would take on this role. An influx of foreign investment would have triggered growth without requiring the Rouhani administration to pursue difficult political gambles, such as expanding government expenditure for growth investments in the same period in which welfare programs are being culled. Moreover, the administration’s budgetary leeway was significantly reduced given the persistently low price of oil, making any such balancing act even more fraught.

Eighteen months after Implementation Day, it is clear that the administration significantly overestimated both the attractiveness of the market and underestimated the hesitation of major banks to resume ties with Iran. Investing in Iran is neither easily justified nor easily executed.

The country lacks two essential qualities that have characterized most emerging and frontier markets in the last decade. First, most emerging economies are not as diversified as Iran’s, and do not have such a large arrange of incumbent players with whom any foreign multinational or investor will need to compete for marketshare. There tend to be more “greenfield” opportunities in which lower capital commitment can generate higher returns. Second, a nearly universal feature among emerging markets is the consistent application of both expansionary monetary and fiscal policy. Such policy makes it possible for each investor dollar to achieve a higher return.

In its commitment to reduce interest rates and return the debt markets to normalcy, the Rouhani administration is pursuing an appropriate monetary policy—eventually lenders will become active again. But what remains perplexing is the insistence on austere government budgets in the face of low commitment from foreign investors.

It is clear that the Rouhani administration cannot easily spend tax and oil revenues on long-term projects. Oil revenues are stagnant and there is limited political will to raise taxes. At current levels of government revenue, the political risks of such expenditure are high; as the presidential election showed, populism remains a potent rallying cry among Iranian voters. But foreign investors can’t be expected to step into the gap. Direct equity investments remain a hard sell when domestic financing, whether in equity or debt form, remains throttled and liquidity challenges abound.

There is however a feasible solution that has seen much discussion, but little action—Iran’s return to international debt markets. A sovereign bond issue would both provide Iran’s government the opportunity to raise expenditures in a way that does not draw from existing sources of state revenue by providing a wide class of investors exposure to Iran’s expected period of economic growth. Such a security, ultimately backed by the country’s oil revenues, would serve to mitigate perceptions of country risk for creditors.

In May of 2016, Iran’s finance minister Ali Tayebnia disclosed that discussions were taking place with Moody’s and Fitch over restoring Iran’s sovereign credit rating. One year later, the debt sale continues to be a point of discussion. Recently, Valliolah Seif, Governor of the Central Bank of Iran, commented that the country will issue debt “when [Iran] becomes certain that there is demand for [its] debt.”

Seif’s comments allude to the essential problem of Iran’s planned debt sale—marketing. In order to get Iranian bonds onto the market in any substantial way, the country would need the support of major international banks to serve as underwriters. But banks remain hesitant due to sanctions and political risks.

Turkey, a country which presents creditors significant political risk without mitigation of oil revenues, was able to raise USD $2 billion in a Eurobond sale in January of this year. The sale was underwritten by Barclays, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs and Qatar National Bank.

Iran, is fundamentally a more attractive investment opportunity than Turkey. But major banks remain hesitant to provide financial services to Iran. The Rouhani administration needs to make the sovereign debt sale a core focus of its dialogue with European and global counterparts, and insist on political and technical support in order to entice 2-3 major banks to come on board. In the same manner that the Joint-Commission oversees implementation of the Iran nuclear deal, a multidisciplinary working group needs to be formed to manage the implementation of the debt sale. With the right stakeholders engaged, one can a combination of early-mover banks from Europe, Russia, and Japan agreeing to underwrite the bond issue.

Encouragingly, the delays may have played to Iran’s favor. Emerging markets are just now beginning to rebound, and investors have driven sovereign debt sales to record highs. The Rouhani administration must seize this opportunity and move beyond the limitations of its present austerity economics.

Photo Credit: Wikicommons

The Stage is Set, But Will Rouhani Deliver in His Next Act?

◢ A resounding election victory has renewed Rouhani's popular mandate, but following President Trump's speech in Riyadh, the prospects for improved US-Iran ties remain remote.

◢ But by taking the high road, Iran can still make progress in its international relations, especially if it aims to forge deeper ties with Europe.

Last Friday, Hassan Rouhani emerged victorious in Iran’s contentious election, winning nearly 60% of the vote in a contest which saw 72% turnout. The clear victory confirms the incumbent’s popular mandate, and reflects the electorate’s belief that he remains the only politician able to lead on Iran’s wide range of economic, political, and social challenges.

Crucially, his chief opponents Ebrahim Raisi and Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf were unable to present a cohesive alternative to Rouhani’s economic program, relying instead on unrealistic promises to expand welfare handouts to Iran’s lower classes.

The promises of greater handouts had an undeniable appeal, however, as voters aired their frustrations with the lack of improvement in their standard of living during Rouhani’s first term. While growth has rebounded since the lifting of international sanctions, stubborn unemployment and wage stagnation have left the average Iranian patiently waiting for the much touted windfall of the nuclear deal. Nonetheless, Iranian voters understand that international engagement is a precondition of any eventual improvement in their economic fortunes. In a boon to electoral fortunes, Rouhani and his administration were widely and credibly seen as the most effective advocate for Iran’s international relations.

Yet, just two days after Rouhani’s victory, American President Donald Trump issued a scathing address from the specially-convened Riyadh Summit, during his first overseas trip. Trump’s speech, issued in concert with the Saudi leadership, cast Iran as a chronic human rights violator and the leading supporter of international terrorism. He called for the international community to isolate Iran.

The juxtaposition of Iran’s energetic and significant popular vote (driven in great numbers by Iranian women voters), with the cynical pageantry of the Riyadh Summit, held in a country where elections do not occur and in which women have limited freedoms, could not have been more stark.

While the Trump administration has quickly aligned itself with the particular vision of Iran espoused by Saudi Arabia and its Persian Gulf allies, the rest of the international community has watched the weekend’s events with greater pause. In the election, Iran put its best foot forward; demonstrating quite vividly that it cannot be caricatured as the destructive force portrayed by Trump, but should understood as a multifaceted country whose civil society is yearning for international engagement.

Though Trump’s speech risked adding fuel to the regional rivalry between Iran and Saudi Arabia, President Rouhani struck a measured tone in his first press conference since being re-elected, noting on Monday that the Saudi people remain Iran’s friends.

Overall, the weekend’s events may actually prove a blessing for Iran. By putting Iran’s better qualities into such clear relief, and by making so transparent the subservience of US foreign policy in the Middle East to an agenda defined by Saudi Arabia, a much wider political space is opening for ties between Iran and the wider international community, especially in regards to relations with Europe.

Senior leaders from the European Union, such as High Representative Federica Mogherini, were the first to congratulate President Rouhani on his reelection. His electoral success will no doubt give greater confidence to the slew of major multinational corporations that have been pursuing trade and investment deals in Iran. At the same time, the elections serve as a validation for the European policy that expanded economic relations can help encourage Iran’s move to a more open and accommodating political and social posture.

Consider also that despite the rhetoric, the Trump administration looks unlikely to interfere with the basic sanctions relief afforded through implementation of the JCPOA nuclear deal. As such, the baseline conditions for Iran’s economic engagement with the international business community have improved significantly.

In order to fully deliver on his promise of economic growth and to more effectively attract investment from industrial players and financial investors, the Rouhani administration must commit to a bold agenda of sustained reform. While his first term was largely focused on addressing fiscal and monetary policy (tightening budgets and reducing money supply in order to tackle inflation, for example), his second term must focus on industrial policy.

Iran needs to quickly decide how it will balance the requirement to support domestic industrialization and job creation with the need to welcome leading multinational companies who wish to bring their products to the Iranian market. A lack of clarity on this issue has meant that many long-standing trading partners in Iran are struggling to get the same support from government ministries and agencies that are afforded to outside companies promising new investment in the country.

This unequal treatment belies a lack of coordination among Iran’s government and business stakeholder groups on issues pertaining to the country’s business environment. European governments and trade promotion bodies could do much more to help transfer best-practices to their Iranian counterparts, helping to support the business development efforts of both foreign and Iranian companies. This kind of technical cooperation, which goes beyond delegations and trade events to address the practical challenges facing the business community across-sector, remains the elusive next step in Europe-Iran ties.

Rouhani’s great success has been to set the stage for an economic resurgence. The question now remains whether he can successfully direct the actors to play their parts.

Photo Credit: Wikicommons

Early Delivery of Iran Air’s First Boeing Jetliner in Doubt

◢ In early April reports suggested that Iran Air would acquire its first Boeing 777-300ER nearly a year early, purchasing a plane originally built for Turkish Airlines.

◢ But the deal now seems dead and the aircraft has not made the expected flight to Victorville, California for repainting in the Iran Air livery.

On April 10, 2017, news broke that Iran Air was to receive its first new Boeing jetliner nearly one year earlier than expected, with delivery slated for mid-May. This was to be the first aircraft of eighty for which Boeing and Iran Air signed a $16.6 billion in December 2016. Deliveries for the order, which include fifty 737 MAX 8s and thirty 777s in two variants, were slated to begin in December 2018.

The aircraft in question was originally built for Turkish Airlines with the registration TC-LJK. Deemed superfluous to requirements before delivery, the plane was to be sold by Turkish to Iran Air, where it would fly with the registration EP-IQA. Prior to reassignment, the jetliner, a Boeing 777-300ER, would need to be repainted in Iran Air colors.

This was to take place in Victorville, California, where International Aerospace Coatings (IAC), a Boeing contractor, operates a program painting liveries for 777 aircraft. Initial reports suggested that TC-LJK would fly to Victorville on April 13 for repainting, following a visit by an Iran Air certification team to ensure the Iranians were happy to acquire the jetliner in its current configuration.

But new reports suggest that the deal has stalled.

Flight data shows that TC-LJK, operating as BOE549, remains in Everett, and has not moved since a short test flight on April 7.

This suggests that the repainting has not been completed. It might be that Iran Air requested alterations to the configuration of the aircraft, which would be made at Everett and would have delayed repainting. But the more likely explanation is that Iran Air is no longer able to secure the early acquisition.

An April 22 post on Paine Field News, a blog site which tracks production of aircraft at Boeing’s Everett factory, cites an unnamed source at the manufacturer to claim that the “Turkish-Iran Air deal for TC-LJK is officially dead” and that Turkish airlines has decided to take delivery of the aircraft as originally intended.

Yet just two days prior, on April 20, the same website cited the same unnamed source to suggest that deal was still alive and that Iran Air inspection teams had visited Everett to view the aircraft.

Something must have changed in the calculation of Boeing, Turkish Airlines, and Iran Air on or around April 21.

It is worth noting that an early delivery of the aircraft to Iran Air became much more difficult on April 19, when Secretary of State Rex Tillerson made an extended address to the press in which he highlighted “Iran’s alarming and ongoing provocations that export terror and violence.” The tone of this address, and the reaction it elicited in the media, certainly meant that there would have been a heightened impact on Boeing’s corporate reputation and that of any facilitating banks had the delivery to Iran Air gone ahead in the subsequent weeks. While Boeing has lobbied that its deal with Iran Air supports American jobs, critics of the deal were buoyed by Tillerson’s apparent acknowledge of concerns over the appropriateness of US-trade with Iran, despite confirmed adherence to commitments under JCPOA.

It may be that Boeing, Iran Air, and Turkish Airlines decided to take a wait-and-see approach on the Trump Administration's rhetoric on Iran. Certainly, even if Iran Air is unable to receive TC-LJK, there remain other "orphaned" jetliners on the market which Boeing can help direct to its Iranian client. An acquisition during the summer remains possible. Given the importance of the Boeing-Iran Air deal as a landmark contract for Iran's post-sanctions trade, the race will be on to make a successful delivery.

Photo Credit: Wikicommons

Iran, Pakistan, and Afghanistan Should Take a Regional Approach to Start-Ups

◢ Start-up ecosystems in Iran, Pakistan, and Afghanistan show great promise, but entrepreneurs in these three countries remain isolated from one another.

◢ These entreprenuers would benefit from more regional programs that encourage collaboration and shared learnings. Programs on offer in the ASEAN countries offer a compelling model.

Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan host some of most interesting and promising start-ups in Southwest Asia. Entrepreneurship and innovation are neither new nor foreign imports to the region. Cities and towns in Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan make up parts of the Silk Road, an ancient network of trade routes that once connected the East and West from China to the Mediterranean Sea. Historically, trade, innovation, and cultural exchanges have flourished along these trade routes.

Today, however, the entrepreneurs of this region operate in isolation from one another. Divergent political ideologies, cultural biases, and economic policies have prevented many entrepreneurs from exchanging ideas and collaborating, rendering them unaware of their neighbors’ achievements in areas of social innovation and entrepreneurship. Knowledge sharing and transfer, if sustained, can highlight the achievements of local and regional social and tech entrepreneurs.

While these three countries engage in active trade individually, building a regional start-up ecosystem would provide a space for entrepreneurs to share their experiences and collaborate further. Because of their shared cultures, histories, languages, and similar economies, Afghan, Iranian, and Pakistani entrepreneurs already share many common characteristics that could foster more collaboration and generate more economic growth and innovation. Therefore, we propose the formation of a regional start-up ecosystem to benefit the entrepreneurs and the economies of the above countries.

Entrepreneurs and ecosystems do not operate in a vacuum. Political, social, and economic realities influence entrepreneurs and shape start-ups. Establishing a regional start-up ecosystem would reduce border tensions, improve overall regional security, promote good governance, and allow the steady flow of goods and services across the region. Meanwhile, entrepreneurs and social innovators should focus on studying and understanding their regional markets, finding opportunities for growth and scaling within their own region.

Pakistan: An Established Player

Of the three countries, Pakistan has the most elaborate and developed start-up ecosystem. Urban areas of Karachi, Lahore, Peshawar, and Islamabad are home to some of the most renowned and internationally acclaimed entrepreneurs and social innovators (e.g payload, Healthwire, Dockit, Meezaj).

Since the security climate in the country has improved, the start-up landscape has grown and attracted venture capitalists from Silicon Valley, Malaysia and the Persian Gulf. The 2012 launch of Plan9, Pakistan’s first incubator, laid the groundwork for the start-up ecosystem. Pakistan is now home to more than 20 start-up incubators and accelerators that provide co-working, office space, mentorship, networking opportunities, and access to investors.

Undoubtedly, Pakistan has the potential to become the next emerging hub in Asia. Both high mobile penetration and the well-developed telecommunication infrastructure have given rise to tech start-ups that have disrupted almost every sector—wedding, health, fashion, payments. Success stories include Convo, a social networking platform, and have captured the attention of international investors.

Shaun Di Gregorio, CEO of Frontier Digital Ventures, a venture capital fund based in Malaysia that has previously invested in Pakistani start-ups, notes that “People who have an appetite for emerging markets will be attracted to Pakistan. It’s considered one of the next big frontier markets.”

Pakistan holds an edge over its regional counterparts primarily because of two reasons. First, Pakistan’s market does not set a limit on foreign equity, enabling investors to hold a 100 percent stake without the help of any local partners. Second, total repatriation of investment capital is allowed. Therefore, every penny earned in profit can be returned to the original investor with ease.

While serving as an example for its neighbors, Pakistan’s start-up scene continues to flourish, there is still work to do. As Khurram Zafar, executive director of Lahore University of Management Sciences’ Center for Entrepreneurship, notes “more bridges are needed between Pakistan and the outside world which are best built by the diaspora looking to stay connected with the country.” This lack of connectivity can be seen in the region. Many Afghan or Iranian start-ups are unaware of the incubators or accelerators that exist in Pakistan and unsurprisingly, there are no Iranian tech entrepreneurs in Pakistan’s accelerator programs such asInvests2Innovate or Peshawar 2.0. Collaboration among these three countries would boost productivity, increase access to investment, and promote their status to emerging markets.

Iran: A Rising Star

Iran’s entrepreneurship ecosystem remains nascent yet promising. In the past decade, Iranian policymakers have shifted their focus to entrepreneurship and innovation and there is plenty of room for progress. Iran’s overall score on the 2016 GEI Index is 28.8%, ranking 80th among the 130 countries surveyed. Among the 15 MENA countries, Iran’s ranking at 14 indicates a weak entrepreneurship ecosystem. Compared to previous years, Iran’s overall score has improved, but it has yet to fully realize its potential.

In 2008, Iranian start-ups such as Digikala emerged in the ecommerce and online retail market, becoming the largest ecommerce platform in Iran. Emulating Amazon, this start-up is considered a poster child for start-up success in Iran. In recent years, fast Internet speeds, high mobile penetration, and official support for entrepreneurship have led to creation of a flourishing start-up scene.

There are many sectors that remain bursting with potential for disruption. They include ride sharing, people to people hospitality, online furniture, design services, and payment delivery. Certainly, there is high demand for these types of start-ups because of Iran’s sophisticated and young costumers, and underserved markets, a legacy of international sanctions which has now been largely removed.

Despite its low entrepreneurship and productivity scores, Iran ranks fifth after India, China, Russia, and the U.S. for having a significant number of talented and well-educated engineers. Consequently, Iranian policymakers should divert their attention fully to exploiting Iran’s impressive human resources toward boosting competitiveness, promoting employment, and raising productivity levels.

Iran’s start-up scene is vibrant led by several savvy Western educated mentors and modeled after successful Silicon Valley companies. Start up Grind and Start-up Weekend events are held throughout the country. However, there too few incubators and those which do exist often struggle to provide adequate financing opportunities to promising businesses. Accelerators exist, but few are run professionally and optimally. Unfortunately, Iranian legal codes do not protect innovation and intellectual property rights. These obstacles have created setbacks for Iranian entrepreneurs, preventing them from robust growth and scaling.

Afghanistan: Underappreciated Potential

Although Afghanistan’s ecosystem and start-up scene is only now starting to grow. Particularly in urban areas of Kabul, Jalalabab, Kandahar, Mazar-i-Sharif, and Herat, new programs are being launched teaching youth how to code, teaching entrepreneurship, and many more related programs to increase capacity, knowledge, and skills.

Among such programs are Shetab Afghanistan, the first comprehensive incubation, co-working, and mentor program in Kabul that is helping entrepreneurs and social innovators. There is also Afghanistan Startup, Startup Valley, Startupistan, and many more that are entering the Afghan start-up scene.. A 2015 survey carried out including 27 start-ups in Afghanistan revealed that 70% of Afghan start-ups fail due to ecosystem and market start-up failures, including access to mentors, infrastructure, and more open regulatory environment, and access to finance. Contrary to conventional wisdom, security is not the top concern facing entrepreneurs. Instead, entrepreneurs face the following challenges: limited access to networks and regional markets, faster internet and related infrastructure, trade friendly regulatory environment, an end to corruption, as well as availability of supportive incubation, acceleration and co-working programs. These gaps can be filled within regional frameworks.

Why Collaboration Matters

It time to put more weight on the effective implementation of new political and economic initiatives, collaborative networks, policies, and programs to regionally link start-up ecosystems across Iran, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

The potential benefits of collaboration across regional ecosystems outnumber the disadvantages. It would lead to increased visibility and publicity for start-ups, offering an opportunity to scale into new regional markets. It would increase technical knowledge that is localized, and could potentially open up entrepreneurs from the region to sorely needed financial and mentor resources. Beyond these concrete benefits, local governments should offer incentives to attract large corporations in these countries. After all, large corporations remain vitally important for ecosystem building because they help investment in the supply chain, contract start-ups, or even possibly acquire the most promising start-ups in the long-run.

Because of the dominant Western-centric narrative widely accepted among entrepreneurs and start-up lovers, there is an overarching tendency for entrepreneurs to take examples from the West and emulate them. Therefore, there is a gap in knowledge among young entrepreneurs in these countries about exciting and new developments in their own backyard. While it is reasonable to emulate Western models, it is equally important to adopt and adjust them considering local conditions, specifically cultures, languages, and lifestyles.

For example, initiatives could include regional conferences like a TEDx talk held in Herat focusing on regional start-ups that can incorporate Tadjik entrepreneurs. Another way to foster brainstorming and collaboration among entrepreneurs could be to swap co-working spaces, as is done in Europe, so that an entrepreneur from Lahore can learn about the Iranian social technology market to scale his mobile geo-app for car parking. In addition, Iranian, Pakistani, and Afghan member investors could use shared Linked groups as a viable means to bridge cultural biases, connect board members, and enable mentor sharing between various accelerator and incubation programs in the region.

Among the most promising initiatives would be to establish a regional exchange and scholarship program between regional universities. Again looking at the region’s ‘backyard,’ the ASEAN (Association of South Eastern Asian Nations) countries have created several programs that support cross-border innovation and collaboration. For example, the very successful ASEAN University Network has helped hundreds of exchange students to study across borders since 1995. The organizations has built partnerships with other renowned universities around the world to promote knowledge sharing, collaboration, an access to opportunity through joint project-work.

Through the ASEAN Center for Entrepreneurship, regional and global initiatives support various start-ups. Recently, the Malaysian government, through its MaGIC Program, has offered ASEAN start-ups access to a regional accelerator funding and educational support services in Kuala Lumpur. Even "pariah state" North-Korea is sending its young entrepreneurs to Singapore, a powerful start-up hub, to help them in business, law, and economic policy and to learn about Lean Canvas (with the help of Choson Exchange, an NGO).

These initiatives provide compelling models of what could be done to support the achievements of local and regional entrepreneurs and social entrepreneurs among Pakistani, Iranian, and Afghan start-ups.

Unfortunately, the international media has failed to present a full and balanced view of Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. Negative images of violence and terrorism have become ingrained in many entrepreneurs’ minds and rendered them oblivious to the achievements of their neighbors in the areas of social innovation and entrepreneurship. Today’s revival of the ancient trade routes as a successful model for a regional start-up ecosystem highlights not only their historical legacy, but also their contemporary relevance to regional commerce, trade, and advancement of Southwest Asia.

Photo Credit: Bourse & Bazaar

In Letter to Congress, Rex Tillerson Sends Positive Signal on Iran Deal

◢ In a letter to House Speaker Paul Ryan, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson has confirmed Iran's compliance with its obligations under the JCPOA, or Iran Deal.

◢ This letter reflects an important shift in the Trump administration's view on Iran, publicly confirming faith in verification processes and indicating an intention to craft policy through formal mechanisms.

Update: Several hours after the publishing of this piece, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson gave a press conference in which he outlined a strongly negative outlook on Iran, underscoring that the administration's review of Iran policy will take into account the full breadth of foreign policy concerns including support for terrorism and human rights violations. The statement can be seen here.

In a letter to House Speaker Paul Ryan sent yesterday, Rex Tillerson, the U.S. Secretary of State, confirmed "that Iran is compliant through April 18th with its commitments under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action." The letter represents the clearest confirmation to date that the Trump administration is in agreement with the international community on the fact of Iran's compliance with the JCPOA, also known as the Iran Deal.

While some outlets misreported that the letter was equivalent to an extension of sanctions relief, it is more accurately a preliminary step, part of the State Department's quarterly reporting to Congress on Iran's compliance with the Iran Deal. The critical date for the extension of sanctions relief arrives in mid-May, just prior to the Iranian presidential elections. At that point, Tillerson will need to formally "waive" the US secondary sanctions on Iran, exercising an authority delegated to him by the President.

The timing of the letter to Ryan, coming just one month before the renewals are required, is a positive signal that the Trump administration will continue to implement the Iran Deal.

To be clear, the letter was not a total break from the relatively hawkish position taken by the Trump administration towards Iran. Tillerson's missive was titled "Iran Continues to Sponsor Terrorism" and it informs Speaker Ryan that President Trump has "directed a National Security Council-led interagency review" to examine whether sanctions relief afforded to Iran is "is vital to the national security interests of the United States." The invocation of Iran as a "leading state sponsor of terror" and the reference to the pending review have led some to see the letter as consistent with President Trump's negative view of Iran and campaign rhetoric in which he described JCPOA as one of the "worst deals" ever negotiated.

However, the letter should be seen as a positive signal for three reasons. First, it is a confirmation that the Trump administration trusts established verification procedures, which include the oversight of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and American intelligence gathering. Many opponents of the Iran deal have tried to cast-doubt on the trustworthiness of both the IAEA assessments and intelligence estimates dating to the tenure of the Obama administration, which have so far pointed to Iran's compliance with the Iran Deal. Tillerson's letter would seem to confirm that these mechanisms of evaluation hold weight for the new administration.

Second, the letter demonstrates an increasing willingness for the Trump administration to craft its Iran policy through normal channels. The interagency review requested by President Trump is a formalized and commonly-used process to determine appropriate national security policy. Given that the composition of Trump's National Security Council has changed considerably since he took office, most notably with the ouster of General Mike Flynn, who had put Iran "on notice" shortly before his demise, there is an improved likelihood that a review conducted at this stage would make a sober assessment of the Iran Deal's consistency with the US national security interest.

Finally, Tillerson's letter reflects that the Trump administration may now have a grasp on the essential challenge it is facing in crafting its policy towards Iran. On one hand, there is considerable pressure from certain congressional leaders and foreign allies such as Saudi Arabia and Israel for the administration to take a much harder stance towards the Islamic Republic. Indeed, it is worth noting that Tillerson's letter coincided with his participation in a U.S.-Saudi CEO Summit hosted by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. On the other hand, the administration has seemingly come to understand that JCPOA is an effective foreign policy tool, one that actually addresses much of the complexity in dealing with Iran. To cease its implementation of the Iran Deal in the face of Iranian compliance would both strain relations with European allies and likely cause further destabilization in the Middle East.

For President Trump, the task will be to remain tough, but reasonable. It remains possible for the Trump administration to be tough on Iran by taking the lead on targeted sanctions designations, such as those levied for Iran's February ballistic missile test. But at the same time, it is also reasonable for the administration to continue the "suspension of sanctions related to Iran pursuant to the JCPOA," as the letter puts it, especially if such suspensions support other Trump administration priorities, such as job creation through limited US-Iran trade.

At this juncture, key stakeholders, including the leaders of American multinationals which stand to benefit from access to the Iranian market, need step-up their outreach to Trump. Encouragingly, the viability of the Iran Deal is no longer "fake news."

Photo Credit: Wikicommons

Extention of Key Incentive Scheme Boosts Iran's Renewable Energy Market

◢ The recent extension of Iran's Feed-in-Tariffs scheme has renewable energy investors pushing to close deals in the next 12 months to take advantage of the strong government incentive packages.

◢ But FiTs won't last forever, and Iranian energy authorities are working to improve the general mechanisms that support foreign investment in Iran's renewable sector, including the use of Iran's first competitive bidding tenders for renewable energy projects.

Since the lifting of sanctions, Iran’s renewable market has emerged as an exciting destination for international green energy developers and investors. Growth can largely be attributed to a generous Feed-in-Tariffs (FiTs) scheme and the government’s continued effort to promote policies that, in combination, aim to strike the right balance between promoting Iran’s renewable market, removing barriers to project deployment, and building the technical capacities of the domestic industry. By looking at some of the recent but important developments in Iran’s renewable energy (RE) market, including the nature of government policies, it becomes clear that the Rouhani administration has set a path for growth enabled by international investment.

Iran’s generous program of green subsidies has been the key determinant of the attractiveness of its renewable market, and with the government’s recent decision to maintain its current FiTs for another 12 months, the market is set to shift into a higher-gear. The extension of the FiTs scheme, which was delivered through a decree signed by the Minister of Energy in mid-March 2017, demonstrated the continued commitment of the government in sustaining the momentum of its favorable renewable energy investment landscape among many of its regional and international competitors. The consistency in the nature of Iran’s renewable policies in the last three years is by extension, a major confidence-building measure for developers and investors, whose interest in a given market is not cultivated by generous FiTs alone, but also by stable and predictable policy environment.

Interestingly, the recent extension Iran’s FiTs scheme comes at a time when in most of other markets across the globe, governments are either reducing, halting or terminating their FiTs schemes all together. This has been a major cause of concern for green developers and investors with huge vested interest in those markets. With a reduction in government incentives and flattened demand in the European market, green developers and investors are now eagerly looking into opportunities in other attractive markets. Iran comes at the top of the list.

Opportunities and Limits of Feed-in-Tariffs

The extension of Iran’s FiTs scheme presents a window of opportunity that will not be around forever, and so the countdown has already begun for developers to take advantage of the existing rates by signing their Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) with Iran’s Renewable Energy Organization (SUNA) prior to March 2018. In light of this, it is projected that this year SUNA will expand its pipeline of renewable projects to be developed by international developers in partnership with local partners.

Currently, Iran’s FiTs scheme stipulates a 20-year PPA framework that supports a series of 13 renewable plants. The structure of the scheme is deliberately designed to increase the solar and wind capacities of the country, while also encourage procurement of smaller-scale projects by offering higher margin of profit for systems under 10MW and 30MW capacities. The reason behind this policy is twofold. On the one hand, it allows an experimental approach, where the impact of the initial projects that are pending construction and connection in this fledgling market can be assessed, and on other hand, it enables for the competence and commitment of developers to be evaluated in smaller projects prior to issuing further licenses for larger-scale developments. For the most capable developers, Iran’s FiTs system and structure simply means a strategy of portfolio aggregation—that is, building smaller projects that can be aggregated at a later stage. Therefore, many of renewable projects that will mushroom across different regions of the country in the next 24 months will consist of solar photovoltaic plants with 10MW to 30MW of capacity.

Nevertheless, the success and growth of Iran’s RE market cannot not rest on its generous FiTs scheme alone. For example, rival renewable markets, such as UAE, Jordan and Egypt, are currently developing and deploying projects on a much larger-scale than Iran without even considering the need to offer a generous FiTs scheme. For example, the launch of Dubai’s recent large-scale 200MW solar project in March, which was implemented at a record-low bid of 5.6 cents per kilowatt-hour, was product of a competitive RE tendering scheme, which is an alternative means of engaging developers.

The rapid pace of progress in the region’s RE markets, has made Iranian authorities ever more conscious that in parallel to providing FiTs, they need to institute and maintain multiple complementary mechanisms, such as competitive bidding tenders. Taking this in mind, the recent announcement of Yazd Regional Electricity Company for its plans to hold Iran’s first RE tender on the development of a 150MW utility-scale solar project is precisely aligned with this new emerging strategy of Iran—that is, to maintain its current FiTs scheme for broadly incentivizing development projects on smaller-scale, while phase in competitive bidding tenders as a new complementary measure to support larger-scale projects.

Project Deployment Mechanisms

In parallel to government’s effort to incentivize this market in the last two years, SUNA has also been hard at work in addressing deficiencies in regulations, removing barriers-to-entry, and setting a viable and functioning mechanism for project procurement and development. Designing an effective implementation framework, is in many respects the most challenging part of the puzzle for new emerging renewable markets, such as Iran. It requires a significant deal of coordination between various bureaucracies and organizations, followed by a synchronization of relevant policies and regulatory frameworks that enable project procurement and development. The good news is that the Iranian RE market has made great strides in this regard. The successful launch of the 14MW Hamedan solar park in February 2017, followed with the upcoming launch of Esfahan 10MW solar park, would not have been possible without a functioning project development mechanisms.

The achievements of SUNA in responding to many of technical and non-technical impediments of project implementation framework and regulation deficiencies means that the organization can now expand its activities into other important areas, such as more active investment promotion activities.. This includes establishing and developing new synergies and facilitating dialogue with international RE bodies for learning best practises in areas of policy, technology and financial resources, while also engaging with both local and international financial investors to provide the necessary project finance facilities. The recent delegations from the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) and the Norwegian Export Credit Guarantee Agency to Iran to hold meetings with SUNA reflect the increased communication and engagement of this organization with international stakeholders and bodies.

Building Technical Capacity

Support for renewable energy will not only bring numerous environmental benefits, but will also have significant economic yields for the country. The RE sector can important source of job growth should investment support local capabilities and infrastructure. Iran’s renewable market, despite in its infancy, has already inspired countless entrepreneurs to set up localized businesses in the value chain of renewable power generation and development solutions.

This has not gone unnoticed by the government, which has particularly designed its FiTs scheme in order to foster technical capacity within the industry. The program supports local businesses and entrepreneurs active in this field by allocating a premium of up to 30% on base FiTs rates to those projects that utilize locally-produced content. This premium is attractive enough to encourage international developers to maximize integration of domestically produced technologies, or to explore new local manufacturing of key components.

The next generation of Iranian electrical engineers and technicians has already demonstrated resilience, technical expertise and an entrepreneurial-mindset by not only creating and supporting the value chain of electricity generation of the country, but also exporting their services, equipment, and technologies to the regional markets. To demonstrate, Iran’s power industry, exported over USD 3 billion in electric engineering services and goods to the regional market last year. Aside from supportive policies, the long-term potential to use Iran as a launchpad for regional expansion, sets the country's renewable energy market apart from its regional rivals. Investors are beginning to take note.

Photo Credit: Financial Tribune

Boeing, Iran, and American Jobs

◢ The first new Boeing jetliner is likely to be delivered to Iran Air later this month in what will a historic moment for US-Iran relations.

◢ Boeing's deal with Iran Air represents a unique instance in which an American company's exports to Iran directly support American jobs. This simple fact may provide a framework on which US-Iran ties could be stablizied during the course of the Trump administration.

This article was originally published in LobeLog.

New reports suggest that Iran Air’s first new Boeing jetliner could be delivered within the month.

According to Reuters, Boeing is reallocating a 777 originally designated for Turkish Airlines. This would be the first aircraft of eighty for which Boeing and Iran Air signed a $16.6 billion in December 2016. Deliveries for the order, which include fifty 737 MAX 8s and thirty 777s in two variants, were originally slated to begin in December 2018.

The early deliver will be a boost to President Hassan Rouhani’s reelection push, and follows Boeing’s announcement last week of its second agreement to sell passenger airplanes to an Iranian airline—a deal to sell thirty 737 MAX 8 airplanes to Iran Aseman airlines, valued at $3 billion.

The Iran Air and Iran Aseman deals are among Boeing’s largest open orders and come at a time of softening demand for commercial aircraft among the world’s airlines.

Expectations are also high for the deal within the Iranian business community. Many business leaders in Iran, as well as their European peers, see the Iran Air and Iran Aseman contracts as important bellwethers of the willingness of the United States to continue to implement sanctions relief commitments under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) nuclear deal. Specifically, the deals are a test of whether the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Asset Control will continue to provide licenses to both American and European companies that seek to engage opportunities in Iran. Athough Iran Air and Boeing were able to proceed from a memorandum of agreement to a full contract on the back of an OFAC license issued for the relevant transactions, the license was granted in the final months of the Obama administration. The Iran Aseman deal, which is currently limited to a memorandum of agreement, will only be able to proceed to a full contract when the Trump administration issues an OFAC license.

Trump has called the Iran Deal the “the worst deal ever negotiated.” The question is whether he will see Boeing’s opportunity as a redeeming feature.

When Iran Means Jobs

Boeing’s engagement with Iran pits the Trump administration's skepticism of the value of the Iran nuclear deal directly against an avowed commitment to support American jobs, particularly in the manufacturing sector.

Numerous American companies are engaged in business with Iran, either via their non-US subsidiaries as permitted under General License H or on the basis of humanitarian exemptions for the export of agricultural commodities or pharmaceutical products. However, it is rare for the products eventually exported to Iran to originate in the United States. Generally, the exported goods of American companies are produced in a non-U.S. manufacturing facility as part of a globalized supply chain. As such, for most American multinational corporations, engaging in opportunities in Iran may deliver shareholder value but won’t unlikely support American job creation on a large scale.

Boeing is an exception to this pattern. For political and practical reasons, the production of airplanes was never offshored and therefore a direct link exists between the orders placed in Iran and American labor at Boeing’s primary production facilities in Bellevue, Washington and to a lesser extent, North Charleston, South Carolina.

Although Boeing is a large, successful American company, it remains politically delicate to pursue business in Iran. Cognizant of this fact, the company has sought to speak Trump’s language when discussing its sales to Iran.

Boeing has highlighted American manufacturing jobs as a fundamental consideration of both the 2016 deal with Iran Air and the recent deal with Iran Aseman. According to Boeing’s official statement on December 11, 2016 announcing the deal to deliver airplanes to Iran Air, the sales will “support tens of thousands of U.S. jobs directly associated with production and delivery of the 777-300ERs and nearly 100,000 U.S. jobs in the U.S. aerospace value stream for the full course of deliveries.” Similarly, the April 4, 2017 announcement of the agreement with Iran Aseman noted “an aerospace sale of this magnitude creates or sustains approximately 18,000 jobs in the United States.”

Boeing’s government relations outreach isn’t limited to public statements. Following Trump’s public lambasting of the company for the cost of a proposed replacement for Air Force One, Boeing CEO Dennis A. Muilenburg has made it a priority to build a direct relationship with the Trump, first meeting with then-president-elect at Trump Tower on January 17. One month later, President Trump visited the Boeing facility in North Charleston, South Carolina which manufactures the 787 Dreamliner. That Trump visited the North Charleston facility rather than the larger Bellevue, Washington facility likely reflected the fact that Trump carried South Carolina in the election, but lost Washington state. Perhaps conveniently, North Charleston is the main manufacturing facility for the 787 Dreamliner, which has not been ordered by Iran Air or Iran Aseman.

After touring the facility, Trump presided over a rally attended by Boeing workers and Muilenberg. “My focus has been all about jobs. And jobs is one of the primary reasons I'm standing here today as your president,” he declared. “I will never, ever disappoint you. Believe me, I will not disappoint you.”

Given the clear parallel between Trump’s speech and Boeing’s positioning of its deals with Iran, it is highly unlikely that Muilenburg and Trump did not discuss Boeing’s Iran business, although there has been no public statement to this effect. It is likewise unlikely that Boeing would have proceeded with the deal with Iran Aseman unless it was reasonably confident in the viability of the deal. Certainly, the executives at Iran Aseman, a privately held airline that has not yet announced a similar deal with Airbus, would have insisted on Boeing’s assurances that the aircraft deliveries were politically viable.

Boeing’s Commitment to Iran

Boeing’s commitment to Iran requires not just political resolve, but also long-term thinking. Not only will these deals take many years to come to fruition—the Iran Air deliveries set to begin in earnest in 2018 and the Iran Aseman deliveries only in 2022—but the full extent of the export opportunity represented by Iran will only materialize over the next two decades.

There are three key considerations that Boeing needs to make. First, the company’s ability to supply aircraft to Iran is of great significance given that it has only one other true global competitor in Airbus. If Boeing is unable to fulfill these agreements it will no doubt lose significant orders to the European giant.

Second, Iran’s current orders are primarily focused on the modernization of existing fleets and the addition of capacity on existing routes. At the moment, Turkish and Emirates Airlines have significant market share in Iran’s international travel market from Iran because of their ability to operate more flights from destinations in Iran to Europe through their respective hubs in Istanbul and Dubai. European airlines have also made significant inroads in the market in the last two years. For example, although Iran Air only operates flights from Tehran to London three times a week, British Airways now operates a daily service. At the same time, an aging fleet makes Iran Air unappealing to travelers and hurts the airline’s ability to compete with international carriers.

In the next decade, during which time existing fleets would have been modernized, Iran’s economic recovery and its favorable geography should combine to further boost tourist and business travel to Iran from a wider range of international markets. Indeed, the IATA has forecasted that Iran’s passenger volume could rise from 12 million passengers today to 44 million passengers in 2034.

Iran Air currently flies to about 50 destinations worldwide. By comparison, Turkish Airlines, leveraging the geography of its Istanbul hub, now flies to 296 destinations worldwide. It’s unlikely that Iran Air or any Iranian airline has the financial resources and market conditions to become a “mega-carrier”—and indeed these airlines are beginning to struggle. Still, Iranian carriers have significant room for growth, particularly in serving “transit” roles, which means that further orders are possible, especially for long-haul aircraft like the 787 Dreamliner.

Finally, Iran’s most commercially successful airline is privately held Mahan Air. Mahan continues to be listed on the OFAC Specially Designated Nationals (SDN) list for the use of its civilian aircraft in airlifting troops and munitions from Iran to Syria. But it’s fleet size of 50 aircraft is significantly greater than Iran Air’s 29 aircraft, and it flies to more destinations with greater regularity and a higher passenger volume. Should Mahan reform its business practices and clarify its ownership, Boeing and Airbus could be competing for another significant set of orders.

Framework for “Business Diplomacy”

For the above reasons, Boeing’s engagement with Iran isn’t about a couple of one-off transactions. It is about a longterm commitment to a market that will generate substantial orders over the next two decades. From a political standpoint, this makes Boeing’s foray into Iran so important.

Whereas US diplomats have no access to Iran and limited direct dialogue with Iranian counterparts, American executives are opening substantial channels of communication. In this sense, leaders like Muilenburg become the unlikely interlocutors between pragmatic commercial and governmental stakeholders in Iran seeking to engage US-Iran relations on a transactional basis, and the American political establishment, most notably President Trump himself.

Boeing’s deals could help build a framework on which to develop US-Iran ties in the coming years. In some respects, Boeing’s situation echoes the aborted Conocophillips oil exploration and production deal from 1995. Likewise heralded as a rekindling of US-Iran ties, the Conoco deal died at the hands of congressional pressure and sanctions legislation. But the Boeing deal may have better prospects for three reasons: it does not require an investment in Iran, the sale of new and safer airplanes principally benefits the Iranian people, and most crucially, it supports American jobs.

The Boeing deals need their own “implementation.” This process will keep critical commercial and political stakeholders engaged in a discussion about what constructive engagement with Iran can achieve. In its first phase, under the auspices of President Trump, the scope of engagement will likely remain limited to protecting aircraft manufacturing jobs. Let’s just hope he doesn’t let the workers down.

Photo Credit: Iran Aseman

Slowly But Surely, Lake Urmia Comes Back to Life

◢ Lake Urmia was once the second largest salt-water lake in the world. But years of environmental mismanagement saw the surface area of the lake shrink by 90%.

◢ After a decade-long initiative led by the United Nations, and supported by the Iranian and Japanese governments, water levels in the lake are finally beginning to rebound.

This article was originally published on the United Nations Iran website.

Life has returned to the dying Salt Lake in North-West Iran. The effort to restore what had been broken is succeeding.

Returning to the barren landscape after almost four years, I was able to see water. Not nearly enough, but much more than last time. The lake is reviving. And this revival is the result of an immensely successful collaborative effort involving many players—some Iranian, some foreign.

Lake Urmia was once Iran’s largest lake. In its prime, it was the second largest saltwater lake in the world. But years of man-made disruption—from the frenzy of 60 years of dam-building to the massive over-use of feeder rivers—had diverted the natural flow of sweet water from the surrounding basin into the salty lake. As a result, it simply dried out. It died at the hands of humans.

I also remember thinking that if the lake dried up two main things would happen. One is that salt from the dried lake bed would blow around and get dumped on farming land and crops in what essentially becomes a salt dustbowl in a fairly large radius around the lake. Secondly, we could expect people to get sick. For example, in the vicinity of the dried-out Aral Sea in Central Asia, we already see people afflicted with allergies and respiratory diseases including cancers.

But there would be a third self-destructive phenomenon at play as well. As farmers drilled ever-deeper to pump out the aquifers at the side of the lake for farming, over-exploitation of this groundwater surrounding the lake would cause saltwater seepage into those very same wells. This would hit people’s access to potable drinking water. So we were threatened by a “perfect salt storm” affecting people’s health and livelihoods.

When our plane landed in Urmia two weeks ago, having taken the normal one hour to fly from Tehran, I wondered what I would see. I had heard tell of an improvement. But such stories often vanish in the face of requests to provide evidence. I wanted to see for myself.

It was when we started to approach the vast open expanse of lake bed that I saw the morning sun glimmering off something which had not been there when last I travelled to the lake.

Water. Not deep. But enough to cover the salt dust granules which had caused such havoc before. As we drove across the bridge which bisects the lake, the glimmering started to stretch out towards the rising sun.

I must confess I was so happy that tears were welling up in my eyes. The environmental problems we create can be fixed, I thought. And here is how it happened.

First, some numbers.

When Lake Urmia was full, say 20 years ago, it was estimated to contain around 30 billion cubic meters (bcm) of water. At the worst point, 3 to 4 years ago, it contained a mere 0.5 bcm of salt water. The number now stands at 2.5 bcm. The deadly decline has been reversed. The amount of water now keeps increasing each month.

Use slider to see before and after.

Three to four years ago, when the water level was at its worst, only 500 of Lake Urmia’s 5,000 square kilometer surface was covered by any water at all. That figure has now risen to 2,300 square kilometers. Admittedly, much of that water is spread extremely thin, and some tends to evaporate easily. But it is there, offering a protective covering for the estimated 6 billion tons of salt and dust, which now no longer finds its way so easily into the air, into our eyes and lungs, and onto the farmers’ crops.

Because the amount of annual precipitation in terms of rain and snow in the basin has not changed appreciably in the last few years, we must look elsewhere for an explanation of why the lake is now filling up.

There are three main reasons. The first is engineering works to help unblock and un-silt the feeder rivers. Second is the deliberate release of water from the dams in the surrounding hills. Third, and most difficult of all to accomplish, has been a change in the way water management in the basin happens—especially among farmers. Other approaches like banning illegal wells have also had an impact.

The third approach—better water management—took considerable time and effort to achieve. But it appears here to stay. While practicing new roles and partnership of local authorities and communities within LU restoration process, it took painstaking effort to get farmers to reconsider how they grow their crops by modifying their agricultural techniques when growing wheat, barley, rapeseed and fruit and vegetables.

The new techniques are astonishingly simple: changing farm dimensions to make for smaller plots which retain water better; not using flooding as a form of irrigation, but rather trickle-irrigation which is targeted at the crops and thus not wasted; avoiding deep tillage which causes unnecessary water loss; introducing drought-resistant crop strains; ploughing plant residue back into the soil rather than burning it.

Across the board, the crop yield—despite using less water—has also increased by 40 per cent.

Use slider to see before and after.

Here is a final reassuring set of numbers. Considering the normal hydrological conditions, the lake has an average of 5.4 meters and the maximum depth in northern part around is around 15 meters. When the lake was at its worst point, the lake’s average level had dropped to almost zero. When we compare the level of the lake taken now with what prevailed at exactly this time last year, we note a 6 centimeter rise. The monthly increases have been incremental, but sustained.

The project which has brought about the improved water management is being implemented by the UN Development Programme (UNDP). Based in West and East Azerbaijan provinces with a focus on Lake Urmia surrounding cities and villages, it works closely with local farmers, provincial and national governments and others to initiate an adaptation process by implementing the “ecosystem approach."

Following a 7 year project to introduce ecosystem approach for saving Lake Urmia, with the generous financial support from the Japanese government in recent years, as well as an inflow from the Iranian government’s own resources at both the national and provincial levels, these techniques have been successfully implemented in 90 villages. But this number represents only about 10% of the irrigated farming area in the Urmia Basin. Nonetheless, in the areas where the sustainable agriculture is being practiced, there is a water saving of about one-third of the water that would otherwise have been wasted under the old inefficient practices. This saved water can flow back into the lake, thereby replenishing it.

UNDP’s interventions to save Iranian wetlands including Lake Urmia—starting 12 years ago, but intensifying significantly with the addition of three phases of Japanese funds—have focused on working with local farmers, cooperatives and government to support a new model of partnership among stakeholders and initiate an adaptation process by implementing sustainable agriculture techniques. It has also advocated alternative livelihoods for women using micro-credit and biodiversity conservation.

At present the project’s interventions cover sites all around the lake, and most affected, part of the lake basin. To boost coverage from 10%, the plan is to move towards significant upscaling of this important initiative in an emblematic effort which is being recognized at an international level.

As I got on the plane to return home to Tehran in the evening, three takeaway lessons occurred to me.

First, we face powerful environmental challenges in Iran. But we can fix what we have broken. And this is happening—right now—in Lake Urmia.

Second, the public must educate itself and speak out on the environment. The UN received a petition in 2016, containing 1.7 million signatures, requesting action on Lake Urmia. The pressure has been relentless. Such pressure must be welcomed and acted upon.

Third, in the final analysis, these environmental problems cannot be solved if we act alone. The Lake Urmia response shows that it takes leadership by public authorities, acting in collaboration with the affected communities, and sometimes with support from the international community (technical support from UNDP and financial support from a partner like Japan) to do the trick.

What has happened in Lake Urmia is an example to inspire us all—both within and beyond Iran.

Photo Credit: United Nations Iran, Nasa

In the Future, Iran's Biscuits Will Be Made by Robots

◢ Automation will fundamentally change labor markets around the world, with the deepest impacts being felt in the manufacturing sector.

◢ While foreign direct investment in Iran will support job growth in manufacturing in the near-term, eventually the push for efficiency gains will include automation and workforce reductions.

Some of Iran’s most popular biscuits are manufactured in a facility about an hour south of Tehran. In the tea drinking country of Iran, biscuits are a staple, served to guests in living rooms and boardrooms alike. The biscuit company in question has been in business for over 50 years and occupies several buildings which house production lines for butter biscuits, chocolate cookies, and flavored wafers.

While the scents are those of a bakery, the factory’s sights and sounds are completely industrial. Conveyor belts whir on several parallel production lines, arranged in the long central hall. The oldest equipment in operation was made in 1961 by English equipment maker Simon-Vicars and can bake 500 kilos of biscuits per hour. The majority of the equipment is made by Germany’s Werner & Pfleiderer, with two lines installed in the 1970s and a third line installed in the 1990s. These ovens can bake up to 900 kilos of biscuits per hour. The most modern equipment in the factory are the two Italian Imaforni ovens, purchased second-hand, which can bake up to 600 kilos of biscuits per hour. However, the Imaforni machines are often dormant.

Across the production lines, only the mixing, baking, and cooling processes are mechanized. Packaging of the biscuits is done by hand by teams stationed at the end of each line.

In a building next door to the main factory, the baking of more complex wafer cookies requires even more human input. Not only is packaging completed by hand, but the assembly of the wafers requires the sheets of pastry to be manually fed into the machine that applies the filling.

Altogether the factory employs just under 200 people and boasts a maximum production capacity of 11,000 tonnes per year. With dormant production lines, the output is really about half that figure. By way of comparison, Mondelez International’s factory at La Haye-Foussiere in France produces 45,000 tonnes of biscuits per year with just 450 employees. With greater automation, the La Haye-Foussiere factory employs just twice the number of workers to produce at least four times the biscuits each year.

The owners of the Iranian biscuit factory had one emphatic answer when asked what they would do a new injection of capital: “We would invest in automation.”

Last week, I wrote about the importance of the blue-collar workforce to Iran’s economic recovery, and how post-sanctions growth needs to serve this stakeholder group. While in the short-term, there is clear evidence that foreign direct investment will support the type of economic growth that drives job creation, in the longer-term, the relationship between investment and job creation is less linear. Workers know this and it explains lingering doubts among the working classes about the trajectory of Iran's economic development.

Automation looms large over industrial sectors around the world, and Iran is no different. The arrival of what is being called the “Fourth Industrial Revolution” was the focus of the 2016 World Economic Forum in Davos. The “Future of Jobs” report published during as part of the annual gathering made waves for its prediction of rapid and dramatic shifts in the composition of workforces worldwide. The report predicted over 1.6 million lost jobs in the manufacturing sector by 2020 across a sample of 20 countries that included developed economies such as the United States, Germany, and Japan, as well as rising economies such as China, India, Brazil and South Africa.

While Iran was not one of the country’s sampled in the report, the findings did cover Turkey, which is a strong proxy for Iran given the similar size and composition of its labor force. Employment in the manufacturing sector will actually increase in Turkey through 2020. Similar increases are forecasted for Mexico and South Africa. The report evidences how the pace of economic growth in emerging markets in the next 5-10 years will mean an expansion, rather than contraction in blue-collar jobs. The trend should hold true for Iran.

However, the report’s authors also note that the implementation of automation technologies will only begin to gain momentum globally between 2018 and 2020, when “Advanced robots with enhanced senses, dexterity, and intelligence” which “can be more practical than human labour in manufacturing” begin to account for a greater number of the roles on the production line. Realistically, the adoption of these expensive technologies in less-developed economies such as Iran will take place later, but as adoption increases the next generation of automation technologies will become less expensive in the same period when Iranian labor begins to grow more expensive as wages rise during the post-sanctions economic recovery. This combination of events will make automation even more appealing. Inbound investment will be used to improve efficiency and productivity in the manufacturing sector and capital intensive automation will be justified based on economies of scale made possible as Iran’s exports rebound.

Already, companies like German robotic arm manufacturer Kuka have helped modernize the assembly lines at Iran Khodro and other Iranian automakers. While such improvements to efficiency have helped Iran’s auto-industry become more competitive by international standards, thereby justifying the new wave of potential investment from the likes of Renault, Daimler, and Volkswagen, the long-term profitability of these sectors could depend on reductions to the workforce.

The experience of European automakers in their domestic markets is instructive. On average, a European Union auto worker produces the equivalent of 7 vehicles per year. In Iran, which has approximately 500,000 autoworkers and an annual vehicle production of about 1 million, the worker-to-vehicle productivity ratio is just 2. In the medium-term, an improvement in Iran’s productivity ratio would necessitate both increases in automation and also reductions to the workforce.

For the Rouhani administration, this presents a stark dilemma. How do you usher in an economic agenda to serve the people, if the new agenda will also usher in technologies that could upend employment opportunities for the working classes?

Over the last few years, many of Rouhani's critics have taken to labeling him a neoliberal, the implication being that his pursuit of economic growth will come at the expense of blue-collar workers. Rouhani's ability to address the concern will depend on his ability to ensure that "knowledge transfer" follows investment.

When asked how they intend to manage impending shifts in labor markets, 65% respondents in “Future of Jobs” report cited “reskilling current employees” as the fundamental strategy for basic industries, including blue-collar work such as manufacturing and construction. But while rich countries like Switzerland and Sweden that face this dilemma can experiment with ideas such as universal income or mass retraining of the workforce, for Iran, these issues are far more delicate.

As World Economic Forum founder Klaus Schwab and board member Richard Samans write in the preface of the report:

It is critical that businesses take an active role in supporting their current workforces through re-training, that individuals take a proactive approach to their own lifelong learning and that governments create the enabling environment, rapidly and creatively, to assist these efforts.

For the biscuit company, the opportunities to retrain staff for new roles are numerous. Whereas 200 individuals work in the company, just a dozen are involved in the distribution and sales of the company's products. There are essentially no formalized teams in sales and marketing, business services, retail partnerships, human resources, or corporate and legal affairs despite robust annual revenues. So while the overall proportion of manufacturing labor may decline, the growth of companies like the biscuit maker, should also open the door to opportunities in other job roles.

Looking to the breakdown of the Mondelez workforce in the UK, of the 5000 total employees, two-thirds are directly involved in manufacturing. By this standard the Iranian biscuit company should have nearly 10 times the current number of commercial staff given the size of the manufacturing staff.

Indeed, the "Future of Jobs Report" forecasts job growth in business and financial operations, management, and sales functions across the sampled countries. For Iran, the challenge will be to make sure blue-collar employees are empowered to make the leap into these new roles.

Photo Credit: Bourse & Bazaar

The Other "Forgotten Man": A Look at Iran's Blue-Collar Workforce

◢ Iran's blue-collar workforce is the backbone of the country's economy, but has been largely overlooked by international policymakers and business leaders as a key stakeholder group.