The Brexit Risk to the Iran Deal

◢ Brexit is disrupting the key coordinating bodies responsible for implementation of the Iran Deal.

◢ Trade and investment in Iran will not be a priority for key European companies during Brexit volatility.

This article originally appeared in LobeLog.

The United Kingdom has voted to leave the European Union in a historic “Brexit” vote. The myriad ramifications of the vote will only be fully understood in the coming years, but it is clear that Brexit is as much about the return of great power politics as it is about affairs in the European sphere. Ian Bremmer has declared Brexit the “the most significant political risk the world has experienced since the Cuban Missile Crisis.” It should be no surprise that the prognosis of the Iran deal, perhaps the most significant diplomatic achievement of this decade, will be impacted by the British decision to leave the EU.

The vote has certainly made a splash in Iran. Hamid Aboutalebi, Rouhani’s deputy chief of staff for political affairs, tweeted that “Brexit is a ‘historic opportunity’ for Iran” that must be taken advantage of. On the other side of Iran’s political aisle, Brigadier General Massoud Jazayeri has praised the Brexit vote, suggesting that it represents a rejection of American policies. Whatever the logic of these statements, political actors in Iran are clearly watching the Brexit fallout with interest.

But Iranians should be wary of seeing Brexit as a benign event. The uncertainty and volatility now gripping Europe may have a significant impact on the implementation of the Iran deal. Just as Iran was working to reenter the community of nations, relying on the central coordination of the European Union, the political and economic capacity for implementation is being diverted and eroded.

Diverted Political Capacity

Although much of the debate around the progress in implementation of the nuclear deal has focused on the US-Iran relationship and the role of the U.S. State Department, the diplomatic framework for the implementation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) is firmly rooted within the structures of the European Union. Annex IV of JCPOA outlines the creation of a Joint Commission with the mandate to “review and consult to address issues arising from the implementation of sanctions lifting” among other non-proliferation-related responsibilities. Annex IV specifically names High Representative Federica Mogherini as the “Coordinator of the Joint Commission” for implementation of the Iran deal.

Mogherini in turn leads the European External Action Service (EEAS), the diplomatic service of the European Union, which has played the central organizational role in coordinating Iran’s negotiations with the world powers. She was a key figure during the nuclear negotiations and spoke alongside Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif during the announcement that the P5+1 and Iran had reached a historic accord.

Within the EEAS, the Iran file has been held by Helga Schmid, recently promoted to secretary general of the service, in a move to give her more time to focus on the Iran deal. Below Schmid, an expert-level Iran Task Force was established in 2015. The task force, led by Portuguese diplomat Hugo Sobral is composed of seven members and works behind the scenes to iron out a wide range of issues related to implementation. Iran is unique in that it sits above most of the organizational hierarchy of the EEAS. Iran is such a complex issue, and has become so central to EU diplomacy as one of the few success stories of recent years, that the mandate for implementation is handled at the most senior levels.

Whereas EU coordination has been an asset for the Iran deal, it is now a risk. First, the diplomatic fallout of Brexit could monopolize the agenda at EEAS, with the senior leadership diverted from their work on Iran. Second, the greater the seniority of the diplomats, the greater the exposure to Europe’s impending political machinations. David Cameron has announced his resignation, and Francois Hollande and Angela Merkel will likely have to fight to keep their parties in control. The European foreign ministers who are stewarding the Iran deal—Britain’s Hammond, Germany’s Frank-Walter, and France’s Ayrault—are at risk of losing their jobs. Third, Brexit will clearly have an immense and detrimental impact on the political capacity of the EU. Already, surging populist politicians Marie Le Pen in France and Geert Wilders in the Netherlands have called for their own countries to pursue referendums on leaving the union. Whether those votes come to pass, the focus of the political establishment in Europe will turn inward, and the willpower and capacity to lead in the international arena will wane.

Eroded Economic Means

There is no other coordinating body for the Iran deal outside the EU-led framework. The EU’s central role, linking the foreign policy interests of the UK, France, and Germany (the E3 states) enabled JCPOA to emerge from a consensus including the United States, China, and Russia. That consensus was crucial to the promise of sanctions relief, which is the most important aspect of the deal from the Iranian perspective. If Iran does not see an economic boon, the Iran deal is at risk of failing.

Troublingly, Brexit will negatively impact the ability of both the UK and Europe to deliver the economic benefits of the Iran deal. The primary barrier to increased trade and investment has been the hesitation of major banks to engage opportunities in Iran. Banks are concerned about the lingering impact of US sanctions. Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif has leaned on Mogherini and EU leadership to compel the US to provide greater comfort to European banks about doing business with Iran. But they have made only limited progress thus far. Additionally, banks are generally more cautious than before the 2009 financial crisis, and Iran is seen as a high-risk market with only limited near-term upsides. Most financiers and investors were hesitant to put capital into Iran prior to Brexit, and they will be even more hesitant now, slowing the inflow of FDI. As early market activity has shown, Brexit is having a significant downward impact on emerging market assets. Already stumbling, emerging markets like Iran will become a less attractive opportunity if the volatility continues.

The secondary barrier is within the UK itself. Optimists might note that one of the key arguments of the Leave campaign was that freedom from the EU would enable the UK to pursue business opportunities in key emerging markets around the world. Although the focus has been on China and India, Iran would certainly fall into that category.

Indeed, the UK has been trying to drum up trade with Iran for the past two years, but has had little to no success. In 2015, Chancellor Exchequer George Osborne was slated to lead a trade delegation to Iran, but this was cancelled largely due to political concerns from the UK’s regional allies. In May of this year, Sajid Javid, the business secretary, was meant to lead a business delegation only for it to be cancelled as the Brexit debate threw Cameron’s cabinet into disarray. The UK does have a formal “trade envoy” to Iran in Lord Norman Lamont, who has been a supporter of renewed Iran-UK ties for many years as the chairman of the British-Iranian Chamber of Commerce. But Lord Lamont has had limited success mustering British business, and the UK lags far behind France, Germany, and Italy in terms of promised FDI. Iranians find some hope in the fact that Lord Lamont supported Brexit and will thus retain or even gain political influence in the aftermath of the referendum. But faltering political will is not the only challenge facing British business with Iran.

At a structural level, the economic priorities of the UK will change. Although the Leave campaign touted an embrace of new global markets, the initial priority will be to shore up the British economy by ensuring continued access to the European Common Market. This will require that the UK negotiate a free-trade agreement with the EU-27. This process will be extremely complex and lengthy, and as the global law firm Baker & McKenzie notes, “there are concerns that the UK lacks the manpower and expertise required for such negotiations.” Michael Dougan, a professor at the University of Liverpool, has cautioned that, in terms of the push to emerging markets, “Logistically it is difficult to imagine that the UK has the internal diplomatic and civil-service capacity to negotiate more than one or two agreements at a time, let alone sixty or seventy.” The logistical challenge will also face the chief executives of major British and European companies, who will now need to focus their attentions on post-Brexit planning. They will have fewer resources to devote to developing opportunities in Iran, especially at the required senior levels. Practically speaking, Iran will not be a priority in the post-Brexit economic agenda.

A Change in Mindset

The Brexit vote took place a little less than a year following the historic announcement of the Iran deal on July 14, 2015. What is perhaps most shocking for those of us who followed the Iran deal, and rejoiced in that announcement, is the different mindset affecting the political and economic landscape today.

When the Iran deal was announced, it seemed a triumphant example of cooperation and vision where the national interests of seven different countries, representing the global community, eventually produced a single robust agreement. In many ways, Brexit is a rejection of the type of politics that brought us the Iran Deal.

This may be the final consequence, with the hardest impact to gauge. A single national referendum has shaken the collective faith in the project of formalizing consensus and cooperation in international relations. Iran is coming back into the community of nations. But with the potential demise of the EU, that community will seem less welcoming and less hopeful.

Photo Credit: The Independent

Where Iran Sanctions Relief Falls Short

◢ Limitations on the activities of advisors and consultants keeps banks and businesses wary of engaging Iran.

◢ American regulators should offer a sanctions general license to help knowledge transfer take place.

This article originally appeared in LobeLog.

Over the last few weeks, the debate about supposed U.S. obstruction of sanctions relief has reached a fever pitch. Secretary of State Kerry has brushed off criticism from Europe and Iran, making it clear that the US stands by its obligations under JCPOA. He has stated that US sanctions are used “an excuse” to hide the fact that some European companies “don’t want to do business or they don’t see a good business deal.” Jarrett Blanc, deputy lead coordinator for Iran nuclear implementation echoed this sentiment when addressing an Iran business conference in Zurich, the first time the State Department has spoken at such a gathering. He noted that hesitations go beyond US sanctions and that “business decisions, not surprisingly, in fact take into account concerns well beyond sanctions.” These statements have raised concern among deal supporters in Europe, Iran, and the United States that the deal is at risk, especially if momentum doesn’t materialize before the prospect of a Clinton or Trump presidency.

However, the recent debate about obstruction of sanctions relief overlooks the fact that compliance with US regulations requires two steps: understanding the current status of US sanctions on Iran and ensuring that any transaction facilitated by a financial institution doesn’t contravene those sanctions. It is certainly true that the U.S. Treasury and its Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) could do more to elucidate precisely how they will enforce the post-JCPOA Iran sanctions since European financial institutions, given a history of hefty fines, will not tolerate such a degree of confusion and ambiguity. However, even if the US regulations were crystal clear, determining whether a given transaction is compliant will remain difficult. This second dimension to compliance is what banks call “know your customer” or KYC, and it requires a high degree of due diligence to ensure that parties in a given transaction (even the simple transfer of funds from one account to another) do not fall afoul of the remaining US sanctions. Although progress is being made on the first step of compliance, with US regulators and European bankers and businessmen opening a dialogue, the second step remains a challenge with no clear solution.

In order to put banks at ease, the onus will be on Iranian companies to raise levels of transparency and accountability. Moving from a closed, inward-looking economy to one properly integrated into the global systems for finance and trade will require new business practices. This has been well noted in the numerous country reports written by major law firms such as Dentons, Eversheds, and Clyde & Co, as well as advisory companies such as McKinsey, Control Risks, Economist Intelligence Unit, and PwC.Iran understands the need for greater transparency, but the transition is only just beginning. Most Iranian business leaders considered a nuclear deal an unlikely occurrence until quite late in the negotiations. Few began serious preparations for “post-sanctions” business development until after Implementation Day. As a result, only a handful of Iranian companies in each sector can provide investors detailed and reliable materials on investment and partnership opportunities at the present time. Companies often lack clear and comprehensive websites, let alone detailed third-party due diligence reports or feasibility studies for the projects they are touting. As such, the majority of Iran’s investment opportunities are not “bankable”—that is to say an investor cannot have a high degree of confidence in the verifiability of the project at hand. If the investor cannot be sure of fundamental details, then the cautious banks will be even more hesitant to provide financing or simply facilitate the necessary transactions. They will not be able to ensure compliance, even if the US regulations and other relevant sanctions are crystal clear.

The Blind Spot

The majority of the major deals announced since Implementation Day, which have not progressed beyond Memoranda of Understanding, are between European MNCs and Iranian partners who have a historical working relationship. Companies like Airbus, Bosch, Daimler, Danieli, NovoNordisk, Scania, and Siemens are not new in the Iranian market, and therefore the sizeable investments promised can be made with the confidence built from an iterated relationship with the Iranian counterparty. New players are facing an interesting dilemma. They are making country visits to Tehran every week and are speaking with potential partners. But while the initial conversations are almost always positive, making clear the much touted investment opportunities, the mechanics of those deals remain difficult to pin down. Reluctant to lose the positive tempo of initial visits, European companies have attributed that hesitation to the ambiguity around US sanctions—Secretary Kerry’s comments are accurate. These new entrants certainly find it far easier to blame US sanctions than to explain the inadequacy of a potential Iranian partner’s provided information. It is also hard to blame the Iranian companies that have so little recourse and support in actually producing reports and documentation to the standards Europeans desire even in a so-called “emerging market.”

Here, then, is the true blind spot of US sanctions relief for Iran. It’s not so much that banks feel uncomfortable with transactions, but actually that the third-party service providers banks and businesses rely on to provide an objective, verifiable, and bankable picture of a given opportunity, counterparty, or transaction are not able to operate. The same companies that have produced the initial flurry of reports about Iran—management consulting firms, accountancies, credit agencies, and law firms—are finding it very difficult to understand exactly how they can service Iranian clients in the current regulatory environment. These global companies have massive US operations and countless US persons working in an inherently polycentric corporate structure. They are in some ways the most multinational of all multinational corporations. These companies, which act in many respects as the architects of global standards for business practice and governance, are perhaps more hamstrung than the banks, which have relatively ring-fenced corporate structures.

This situation presents the fundamental challenge of unlocking post-sanctions Iran. The investment opportunities exist, and there is a real will to engage both in Europe and in Iran, but actionable information is in short supply. The “big four” accountancies are circling Iran, attending conferences, publishing reports, and sending non-US citizens on country visits. Despite the high levels of interest, however, work has been slow to start. It is time-consuming, costly, and logistically difficult to create a compliant Iran advisory practice within these major firms.

General License H was a much-touted development to the OFAC guidance update to US sanctions on Implementation Day. It authorized “U.S. persons, including employees and outside legal counsel and consultants to provide training, advice, and counseling on the new or revised operating policies and procedures, provided that these services are not provided to facilitate transactions in violation of U.S. law.” In short, US lawyers and consultants can now help US companies and the foreign subsidiaries of these companies get the basic architecture of their own compliant Iran strategy in place. However, the same US persons and the companies they advise, remain explicitly unable to “rely on [General License] H to “export U.S.-origin goods to Iran.” The trouble is that “U.S.-origin goods” encompasses a prohibition on “reexporting from a third country, directly or indirectly, any goods, technology, or services that have been exported from the United States.” Furthermore, beyond the initial permitted consultations, U.S. persons cannot partake in Iran-related “day-to-day operations” of a U.S.-owned or -controlled foreign entity engaging in activities with Iran, “including by approving, financing, facilitating, or guaranteeing any Iran-related transaction by the foreign entity.”

This language raises many important questions for a company whose primary service is advisory. Can the exchange of ideas and information have a national origin such that it would be defined as a service exported from the U.S.? What does “facilitation” mean in terms of consultancy or due diligence work, which will nearly always be insisted upon by one or all of the involved parties? What is the “red line” where the provision of training and advice to help devise a ring-fencing structure for a non-US subsidiary’s Iran business becomes “day-to-day” involvement in the new Iranian venture? Finally, if the advisor is a third party in a given transaction, is there a meaningful point at which the “exportation” of a service is “is intended specifically for Iran,” and thereby prohibited, or in fact intended and performed for the non-Iranian party?

What the US Should Do

We live in a global ideas economy, where some of the world’s most important companies do nothing more than ensure other firms are working in the most intelligent, strategic, and transparent ways. If Iran is going to become a responsible player in the global economy, it needs access to the free market for ideas. US sanctions policy must ensure that channels for the transfer of knowledge and expertise are left open and that the world’s leading advisory firms can take the lead in sifting through the Iranian opportunities, raising capacity in Iranian companies, and providing transparency for European banks and businesses. A new, expanded general license for advisory practices would eliminate the hassle and cost of setting up a proper Iran advisory practice and get the right expertise into the country at this crucial stage. There already exist broad exemptions for activities such as journalism, publishing, and conference organizing, which presuppose an open exchange of information. The spirit of these exemptions needs to be extended to a broader notion of knowledge transfer that allows for holistic compliance-focused advisory services to be provided to Iranian clients without the arbitrary prohibition of activities by US entities.

Policymakers would be hard pressed to find a way that a management consultant or tax expert trying to explain to an Iranian company how the world expects them to do business would contravene the purpose of US sanctions. On the contrary, policymakers might keep primary US sanctions in place until enough knowledge has been transferred to Iran to raise transparency and governance standards. This will enable US regulators to have a greater degree of confidence in the ability of private businesses to themselves judge the appropriateness of transactions at such time that the US is ready to consider a lifting of primary sanctions on Iran. To be clear, management consultants and other advisors are plainly not a panacea for Iran, but they can have a major influence in shaping the direction of intelligent commercial development. Consider the significant role played by McKinsey in formulating Saudi Arabia’s new Vision 2030 plan. Iran needs similar expertise and vision now.

The adage “trust but verify” was bandied by the Obama Administration to explain the methodology of JCPOA. The verification of the IAEA—a third party—was crucial to bringing the nuclear deal to fruition. Rather than complaining about banks and historical fines, we should realize that the economic implementation of sanctions relief under JCPOA will also require its own kind of third-party verification. Kerry is telling the banks to trust that sanctions relief is real, but he isn’t giving them the tools to verify that opportunities are actionable. This is where sanctions relief is falling short.

Marketing Iran: It's Time

◢ Iran suffers from a negative reputation worldwide, which does not match the domestic reality.

◢ Companies must master skills of marketing and communications to offer new perspecitves on the country and what it can offer.

I will be honest. When one of my close business friends invited me to visit Tehran last year, I was very excited but at the same time a bit scared. I remember spending days on google analyzing Iranian culture, reading about other people’s experiences in the country and just trying to get as much information as possible about this country that has this amazing history but at the same time seems isolated and misunderstood by the Western world.

My fears about Iran disappeared the moment I landed in Tehran.

Despite negative portrayals in the media media, the truth is that there is nothing mysterious about Iran and its people. In my personal experience, Iranians are one of the friendliest and open-minded people in the world. Iran deserves a chance on the global scene, like it or not, the country is about to become one of the world’s most important players.

A lot has happened in the year since I first landed in Iran. This November 21-22, working with our wonderful partners from Mana Payam and Aujan Iran, we are organizing the Global Marketing Summit, Iran’s first ever business conference to feature two days of presentations by global marketing gurus.

Organizing this historical event in Iran has been the most incredible journey of my life. In the past five years my company, P World, has organized over 150 business events in 30 different countries. None of them compare to my excitement for the Global Marketing Summit in Tehran.

It is important to note that as an international company we faced serious backlash from some of the countries where we operate due to the fact that we are organizing events in Iran. The Iranian visas in my passport also resulted with me being questioned on numerous occasions by security guards at different airports about my trips to Iran and yes, at the beginning I was a bit nervous. At one point, we were receiving so many negative messages that we were seriously thinking of whether we were making a good decision by organizing an event in the country. You have to understand that we worked very hard to build a global brand and it was very important for me, as the company’s founder, that our reputation remains intact.

After several sleepless nights and very careful thinking I realized one thing. It is everyone’s responsibility, including mine as a foreigner, to help paint the real picture about Iran. It should be our responsibility to position Iran where it truly belongs and to showcase to the world the true possibilities in the country. Iran is a country of amazing potential and intellectual richness, not the enemy that the Western world is afraid of. To create the right image for Iran and Iranian companies will require better strategies in marketing and communication.

The reality is that as Iranian companies open up for international business, they must learn to adapt and follow the trends that the global superbrands are setting. As their customer base expands, they will have to be able to understand the needs of their new consumers and create marketing strategies that reflect the global marketing standards. The aim of our event is to help all Iranian marketers understand the new rules of the marketing game and to help them prepare for the new and exciting times. At the same time, international delegates must gain much needed insights about the Iranian marketing scene and the rules they have to follow if they want to successfully operate in Iran.

Today, as I am packing my bags to travel to Iran, I know that I made the right decision to host our event in the country.

Iran’s time is coming and if you cannot accept this fact, then the loss is completely yours.

Photo Credit: P World

Business Diplomacy Management: A Must-Have Skillset for Iran

◢ "Business diplomacy" has become a key skillset for multinational corporations operating in markets around the world.

◢ In Iran, the worlds of politics and business often collide making these skills part of the formula for succesful management.

As nuclear negotiations conclude and an opening to Iran’s market looms, Western companies with interests in investing in Iran need to prepare their entry strategies carefully. Beyond normal business considerations, Western companies may face challenges with obstacles emanating from outside of their direct sphere of control. To plan beyond “business as usual,” I propose that they consider applying the competencies of Business Diplomacy Management.

After so many years of strained international relations, foreign companies need to understand that Iran comes with a history fraught with political tensions that may impede business as usual. A British and American backed coup forcefully removed the democratically elected Mossadegh in 1953 to reinstall the Pahlavi Shah, who was himself subsequently removed in the Islamic revolution in 1979. Since then relations between the new Islamic Republic of Iran and Western countries have been frosty. The recent JCPOA agreement must be understood within this context.

What is Business Diplomacy?

Business diplomacy focuses on creating an environment suitable for business and reducing risk and uncertainty. It requires that Western companies understand the historical factors which influenced Iran’s economic, political-military, social and cultural forces as they all affect business in Iran today.

Diplomacy and business are not incompatible nor are they totally different. Professional boundaries between business and diplomacy have gradually become blurred especially after the end of the Cold War period. States are championing economic development and trade relations in today’s global economy which is increasingly interconnected and interdependent. Governments use economic and commercial diplomacy to represent their interests abroad and at home. However, companies are less aware that they need to develop their own diplomatic competencies in order to be successful abroad and to be less dependent on information and guidelines provided by their embassies.

Charges d’affaires or economic and trade advisors at embassies routinely read local press, meet with economic decision-makers and write briefs. These briefs are eventually passed on to the private sector by way of the ambassador. Today, the role of these briefs is no longer as important as it once was as similar information can be gathered by local corporate agencies. Multinationals regularly employ agents with local knowledge not only to gather information, but also to act as facilitators in their dealings with local authorities.

Applied to Iran, western companies investing and planning to operate in Iran should anticipate that their managers will be asked to represent their company and communicate to government officials, business partners and non-business stakeholder groups what their company is intending to do in Iran, how the products and services will help Iran’s economy to grow and how their investment will contribute to improving Iranian society at large.

The function of business diplomacy management should be placed close to other core functions of a company investing in Iran. In addition to this, the diplomatic know-how should be a company-wide responsibility and that the business diplomacy function should be under direct supervision of the CEO.

Business Diplomacy Management: The “must have” skillset for foreign investors

The success of any foreign firm’s future investments in Iran will depend not only on commercial prowess but also on sufficient support from the Iranian government. Unlike many other comparable markets, success will also depend on how the foreign investor interacts with non-business counterparts. A foreign investor has to be able to look for commonality of interests while at the same time be able to agree to disagree without falling into the trap of carrying out disagreements through conflicts. In other words, investors moving to Iran need to acquire diplomatic skills to manage the many differences between Iranian and Western business and societal contexts.

Iran’s non-business stakeholders can be very problematic for a foreign investor if the investor does not know how to respond to these non-business stakeholders in a competent and appropriate way. Business diplomacy management is for instance called for to constructively engage consumer groups, religious leaders, or powerful forces like the Revolutionary Guards who run their own businesses and are used to receive a share of Iranian companies’ profits while making the lives of local producers or retailers difficult.

As a consequence of the normalisation of economic and political relations, Iranian firms will face foreign investment and competition in their home markets while at the same time still being asked to pay a kind of licence or protection fee to the Revolutionary Guards. Hence they will be hard pressed to compete against foreign competitors and orient their business towards a more long term business venture.

Being faced by foreign competition and continuous quasi-tax costs, local firms might act very opportunistically and hence might not always be able to honour agreements with Western business partners. Non-execution of commercial agreements might follow generating a sense of insecurity on the side of the Western investor who cannot read the factors that might have led to non-traditional business practices by Iranian counterparts and who might decide to withdraw from Iran in case of broken promises or abrupt change of commitments.

The following skills and knowledge could be useful to a Western investor planning to invest in Iran:

Basic grasp of Iran’s history, specifically its modern economic history, and legal systems.

Cultural awareness, especially with regard to decision making and social norms.

Familiarity with the diplomatic process that led to resolution in the Iranian nuclear talks.

The ability to represent one’s own company in an Iranian context, with considerations for Iranian counterparts, the media, and informal pressure groups

Strategy, tactics, and procedures of negotiations with Iranians as well as recognition of Iranian negotiation behavior.

Implementing Business Diplomacy Management at Firm Level

Diplomatic know-how at the firm level of a Western investor has to be a strategic core competency as defined by Hamel and Prahalad:

“A core competence represents the sum of learning across individual skill sets and individual organizational units. Thus a core competence is very unlikely to reside in its entirety in a single individual or small team.”

Diplomatic know-how should hence be seen as a company-wide responsibility shared by top management and the respective heads of business units. In order to realize this core competence, I suggest that global companies should create a business diplomacy management function consisting of the following elements namely:

Business Diplomacy Office with a dedicated and specially trained staff answering directly to the CEO, or the most senior manager directly responsible for Iran.

Business Diplomacy Liaison in Iran directly reporting to the top manager of the central Business Diplomacy Office at headquarters.

Business Diplomacy Management Information System which contains information pertaining to Business Diplomacy (including the profiles of active non-business stakeholders at the global level and in potentially conflictual areas in Iran).

Development of a business-related socio-political perspective (e.g., Iranian stakeholder analysis).

Mandate to strengthen the overall organizational capacity in business diplomacy management at foreign owned Iran subsidiary.

Positioning the new Business Diplomacy Office under the direct supervision of the CEO should facilitate the gate keeping function of this new unit whose function is to scan the environment, interact with non-business stakeholders and engage in diplomatic missions under close direction of the CEO. Further strengthening of values and ethics linked to business diplomacy could be expected from CEOs who take an active interest in this strategically important function and accordingly support the new office’s operations through appropriate rewards and sanctions and corresponding internal communication campaigns.

Taking care of business diplomacy and ensuring competent application of business diplomacy management would greatly increase the chances of foreign investors to embark on a business venture in Iran that will be sustainable and fruitful for all parties involved in such a post-treaty undertaking.

Photo Credit: The New Yorker

Investing in Iran: A Reality Check

◢ The Iran economic opportunity has been the source of great excitement, and the market is being touted as some kind of “dream land.”

◢ But expectations are beginning to outpace reality and a more sober assessment ofthe reforms necessary to make Iran a winning market is needed.

Since 2013 when moderate President Hassan Rouhani claimed victory in country’s presidential election, many investors have kept an eye on the Iranian market.

Following the July 14 nuclear agreement between Tehran and the world powers, Iran is expected to come out of a three decades-long economic isolation.

Iran which has the fourth largest oil reserves and the largest natural gas reserves, has long been a “dreamland” for many businesses. With the EU sanctions against the country expected to be lifted in the near future, and with the prospect of US sanctions being lifted sometime thereafter, many investors have rushed to Tehran to assess the conditions first hand.

Foreign Investors

For those investors interested in high-risk markets, Iran has never been a no-go land. These investors have kept their presence in the Iranian market, although without much publicity.

But a wider pool of emerging markets investors began to keep a close eye on Iran as signs emerged in 2013 that a nuclear deal between Iran and the P5+1 group of countries could in fact be possible.

Since then, many Iranian companies have played host to foreign businessmen. Some of these foreigners have simply visited the country to have a better assessment of the situation on the ground while others have taken the opportunity to sign MOUs or even contracts with their Iranian counterparts.

With an end for sanctions in sight, some say the surprisingly developed Tehran Stock Exchange could be the first market to attract foreign investors. It may offer the most attractive vehicle for investment.

Tehran Stock Exchange

The 48-year-old Tehran Stock Exchange (TSE), Iran’s primary exchange, features over 300 listed companies classified into nearly 40 industries. The TSE is considered the most diversified market in the region.

Since 1979, the TSE -- which trades a range of shares, funds and financial instruments, including Sukuk and Islamic funds -- has sustained periods of growth in trading and market capitalization.

The TSE was viewed as a “phenomenon” by some in 2013. From 2009 to September 2013, the TSE Price Index (TEPIX) witnessed growth of more than 500%. This growth was achieved despite the lagging Iranian economy.

However, the TSE Overall Index declined 21 percent in 2014. Experts had anticipated such a correction following the sharp increase in prior years, which was largely attributable to inflation hitting the price of listed equities.

Is Iran Worth the Risk?

With an estimated gross domestic product of $406.3 billion, according to the World Bank, Iran has the potential to rank among the top 20 economies in the world. The country boasts a large middle class and has made progress in dismantling subsidies to get its macroeconomic incentives in order.

The country also has a strong, but often overlooked, industrial base. Iran is the 3rd producer of cement and 14th producer of steel in the world. It is also the largest producer of cars in the Middle East.

However, just like any other country in the world, there is a level of risk involved for investment in Iran. Great amount of government involvement in market, high inflation rate (14.2% by end of July) compared to international norms and a complicated legal system are among the risks businessmen and investors have to keep in mind before entering the market.

Tough labour rules, lack of overall transparency and the absence of a single rate foreign exchange rate could also be considered among the risks attached to investment in Iran.

Reforms

Despite all the shortcomings, the government and other state institutions like parliament have been trying to pave the way for foreign investors. The government has offered to sell state assets to foreigners as a step to cut the government's role in the economy and pledged a tight monetary policy.

Following the nuclear agreement, Iranian officials have also introduced packages which have been described as “strikingly pro-market” by experts.

The Central Bank of Iran has also introduced a bill, allowing foreign banks to open branches in Iran without having a local partner and has pledged to unify the foreign currency in the next Iranian year (starting March 21).

Iran’s Securities and Exchange Organization (SEO) which serves as the country’s financial supervisory authority, has also sought to build a trading platform that conforms to international standards. Under its new structure, Tehran’s exchange has been equipped with online trading, an arbitration board to fast-track disputes, enhanced investor protection, digital signature, surveillance mechanisms as well as post-trade systems.

Positive Outlook

But the preparation for post-sanction era has not only been limited to government institutions. Leading private brokerage companies such as Mofid Securities have also taken major steps in that direction. These companies have expanded the range of materials published for their foreign customers. New English-language reports, analysis and data about market trends and investment methods are more widely available.

Back in 2007, when Goldman Sachs named Iran among the list of “Next 11” most promising emerging markets, many investors wished for a day when investment in Iran would be possible. That day is finally here. In its recent report, World Bank has also forecasted a jump to 5% GDP growth for Iran in 2016 if the sanctions are removed.

With the positive consensus around the outlook for Iran’s economy, long term growth seems likely. But in the medium term, trading Iranian stocks could provide substantial gains, if only because of volatility alone.

Photo Credit: The Business Year

Notes on Navigating Tehran's Urban and Cultural Spaces

There is the potential of détente between Iran and the world and conciliatory dialogues are now slowly appearing in major media which had long vilified the country. Iran may provide a more welcoming and more comfortable urban space than many other Middle Eastern cities, some of which are well-trod destinations for Western expats.

Visit the US State Department travel page on Iran and you are presented with a rather worrying image; a mere visit to the country is warned against. Only recently has the UK removed similar warnings.

But the 35-year long political mistrust between the West and Iran is sharply contradicted by lived experiences of foreign tourists and professionals who have been traveling to the country Iran. Following the nuclear deal, we may soon witness an unprecedented growth in their numbers, whether tourists or business travelers.

There is the potential of détente between Tehran and world powers. A changing cultural conversation on Iran— conciliatory dialogues are now a mainstay on major networks like CNN— is presenting a major challenge to worn out representations of the country as a dangerous and undesired place to be avoided.

Tehran is a safe destination for expatriates. In fact, Tehran may provide a more welcoming and more comfortable urban space than many other Middle Eastern cities, some of which are well-trod destinations for Western expats.

Many of Tehran’s desirable urban features— accessible pedestrian paths, numerous public parks, a strong public transit system— are not present in other Middle Eastern capitals. Though crossing the street is a skill to be learned, you can feel safe in the well-designed pedestrian pathways and overhead bridges, or find a quiet space in one of the many public parks of the city, away from the noisy motorcycle engines and frequent honking of stressed drivers.

Then, there is the city’s nearly comprehensive and affordable public transit system. For about ten cents, you can ride the metro from the city’s south all the way to the famous northern square of Tajrish. It is true that the city’s buses are generally not well maintained; you can find broken seats and floors in need of repairs. But it is probably not an exaggeration to say that on a bus passes the station every minute on the rapid transit bus routes.

Where busses don’t go, there are shared taxis (called khatis) that run specific routes for 30-60 US cents and you get to meet interesting people who share the ride with you. At night (or even during the day), you can call one of the numerous taxi service companies located on every few street corners for a private taxi. A ride across the city can cost as little as 5 US dollars and you can always expect your drivers to keep you entertained talking about a variety of subjects with an all-knowing sense of confidence, including their favorite topic, politics. And if they’re having a bad day you’ll certainly be lectured about the terrible state of the economy.

However, what makes Tehran particularly accommodating is the diversity of ideas and lifestyles. The diversities of opinion do not always find public expression, but are nonetheless part and parcel of communal life. In public and especially private spaces it becomes clear that there are plenty of interpretations of politics and religion that that conflict with the state’s official reading or the reading often assumed in the West.

Moreover there is a lot to do for people of different tastes: entrepreneurs, artists, musicians, novelists, social critics, and poets can all find their niche. State practices do create an environment in which freedom of expression and association is pursued cautiously. Yet, Tehran’s creatives and professionals are able to associate and speak in many ways and venues, expressing themselves through the slight seams the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance has left unwoven on its gradually shrinking curtain of censorship.

In short, the religious and irreligious, apolitical and radical, rule-oriented and free spirited can all find their comfort zones in Tehran. It is an increasingly cosmopolitan city. As with life in any metropolis Tehran has its stresses, but these are negotiated by uplifting episodes, exciting happenings, and intriguing company.

As such, the real challenge for Western expatriates will likely not be encountering Tehran as an urban space, but negotiating Iran’s professional culture. In the West (and the United States in particular, where I’ve spent much of my time), professional culture is very much task-and-role based; you are given a task that falls within the purview of your responsibilities and are supposed to complete it irrespective of your relationships with others.

In Iran, relationships really matter. Whether you’re seeking an appliance repair from a landlord, trying to get the attention of colleagues for a new idea you have, or seeking to beat competition to a contract, such interactions will depend on relationship dynamics perhaps more than in Western countries.

Surely, relationships are also important when it comes to who is hired, appointed, granted a contract, or favored in business relationships in the United States and Europe. However, the relationship-based economy runs deeper in Iranian society and specifically in the realm of business. This is not to say that Tehran is necessarily filled with a collective of nepotists with an indifference to merit and their professional duties. But business has its own culture that needs accommodating. The difference in work culture does not necessarily make one side better or worse. They simply remind us of what different cultures value and how each culture goes about carrying out business.

Iranians prioritize the cultivation of a reciprocal, respectful, and congenial relationship before things can get done. For some expatriates, this can be an exciting challenge, while for others it may prove difficult. As Iran’s markets will likely open up to significant foreign interventions in the upcoming years and an inflow of outside expertise, an understanding of its work culture for newly arrived expatriates can prove invaluable for successful economic outcomes.

Photo: Mohammad Ettefagh

Iran’s Risks and Rewards: Could You Be a Successful First-Mover?

◢ Iran is a "game-changer" market, but demographics, macroeconomics, geography, and politics introduce risks that may make companies hesitate.

◢ The role of risk managers is to protect value, but they can and should also create value for their companies through a more proactive style of opportunity risk management.

If you are in politics or business, in the Middle East or beyond, you probably have an opinion about the recent nuclear deal between Iran and the P5+1 and how it is all going to play out. You have probably heard people loudly question how crucial the agreement is, and have likely heard them disagree – ferociously at times – on its consequences for politics and security the Middle East.

When it comes to the business implications, though, the debate falls quiet.

Businesspeople of all stripes describe Iran to me as “our game-changer,” “the wild card” and “a strategic priority.” It would not be an overstatement to say that Iran’s potential re-opening compares to the collapse of the Soviet Union and the emergence of Myanmar (Burma). That said, a series of factors, including demographics, resource base and geography - not to mention diplomacy - make this opening feel a bit different.

Risk is never too far from any conversation about Iran; a justifiable dose of caution permeates many executives’ decisions about how and when to approach the Iranian market. The reasons are several: the experience of banks (particularly European) over the past few years at the hands of regulators (mainly American), all under the close watch of regulators and lobbyists. Round out the list with generous helpings of political risk, legal complexities and corruption concerns, and you can see why amid all of the enthusiasm, not everyone is rushing headlong into market entry just yet.

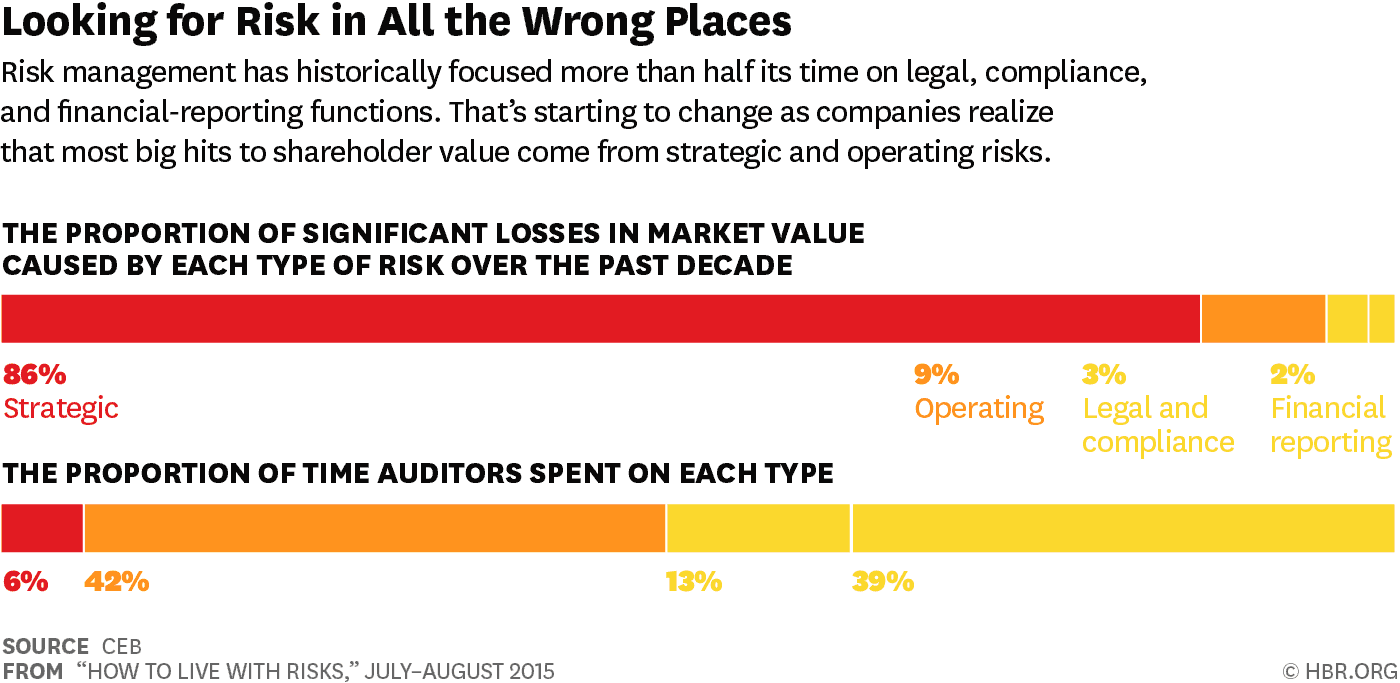

I thought of the two Irans—one of massive commercial opportunity and the other of massive business risk—while reading a recent article in the Harvard Business Review entitled "How to Live With Risks." The article reported on a study by Matt Shinkman of CEB, an organization with 10,000 member companies.

Executives cited in the study said risk managers and auditors prioritized value protection—financial reporting, legal controls and compliance concerns—when seeking to minimize potential threats. In other words, risk management was aimed solely at risk prevention—an exercise in trying to stop bad things from happening.

The article’s research went on, however, to show that mishandling strategic risks—rather than botching tactical risk prevention—does more damage to the long-term value of a company. While 86% of lost market value was attributable to a mishandling of strategic risk, auditors only spend 6% of their time addressing strategic issues.

The lesson is clear. While the risk managers' role is to protect value, they can and should also create value for their companies through pro-active opportunity risk management. They can help to seize opportunities by managing strategic risks and turning them into genuine value for companies, their employees and their stakeholders.

Iran presents most companies with risks that would qualify as strategic. Why else would we be calling Iran “our game-changer,” “the wild card” and “a strategic priority?” Getting Iran wrong sounds like more than just a missed chance.

So it is fair to assume that risk management teams are going to be involved in any well-considered decision about how and when to do business in Iran. The question is: How and when will these teams be involved in your market entry strategy? Will risk managers be asked to look for bush fires, or will they be charged with scanning the horizon for the full complement of challenges and opportunities? If risk management helps build an Iran strategy from the outset, then both internal and external stakeholders can be assured that not only have preventive measure been taken, but that broader issues are under control as well.

Consider a company that has been searching for – and has finally found – a business partner in Iran. The partner meets all the commercial criteria; the terms and conditions have been served up for signature. But wait: has anyone checked whether this partner meets the company's risk, compliance and ethical standards? Fire-fighting risk management is brought in at the last moment. What happens if the partner falls short? Time and money have both been thrown away; an awkward conversation with an eager Iranian partner awaits. Oh, and will there be a chance to start again?

We see this all the time – new opportunities are vetted far too late in the decision-making process and surface uncomfortable concerns that destroy entire strategies.

Proactive risk management prevents this from happening. If business development and risk management work together on partner selection and due diligence, for example, companies create internal alignment on issues of risk. The company’s strategy – and reputation – is under better stewardship, internal resources are not wasted, and deals proceed more smoothly.

In other words, don’t vet mature opportunities, when it’s already too late. Vet your entire pipeline of opportunities at a level sensible to their stage of development.

There’s more. Can an understanding of the day-to-day risks to doing business influence whom you hire in a new market and how you train them? Can monitoring changes in a government’s foreign policy and international relations allow you to anticipate moves like deregulation, and move faster than your competitors? This is where risk management turns into opportunity enhancer. And this is what will make first movers successful.

Today, it’s Iran. Yesterday it was somewhere else, and so it will be tomorrow. The principles of risk management remain the same no matter what the market. But Iran is not just any new market, and there aren’t that many Irans left, which makes the stakes feel that much higher.

Photo Credit: Scania Oghab Afshan

The Rise of Social Entrepreneurship in Iran

◢ There is a vibrant but largely overlooked community of social entrepreneurs in Iran doing innovative work for the social good.

◢ A recent survey of 100 social entrepreneurs completed with the support of George Mason University concluded that while the sector is growing, more support and funding is needed.

The mainstream Western media often fails to present a balanced and positive view on Iran, an emerging market filled with young and visionary social entrepreneurs ("socents") who are actively pursuing innovative and sustainable ways to improve their society and alleviate economic, environmental, and social issues. Emboldened by the recent nuclear agreement reached between Iran and the P5+1 powers, many entrepreneurs are exploring the potential to find solutions to various social challenges by identifying pragmatic tools and resources, which has culminated in creation of startups and social entrepreneurship firms throughout the country. A fast and rising social venture startup scene is hard at work behind the headlines.

Iranian social entrepreneurs are as driven and savvy as their counterparts in San Francisco, New York, London, and Bangalore. They are constantly seeking and implementing innovative solutions, tools, and processes that achieve measurable sustainable impact, while addressing Iran’s pressing social, economic, or environmental challenges. Take Iran’s water problems, for example. According to recent statistics, seventy percent of Iran’s groundwater resources have been depleted. Therefore, groundwater shortages and deteriorating water quality would most likely lead to a national environmental crisis. Certainly, the government alone will not be able to solve such a herculean challenge.

From January to March 2015, we carried out a survey in partnership with George Mason University to map out a preliminary landscape of social entrepreneurship in Iran. Since we were both based in the U.S., we invited trusted and knowledgeable local partners in Iran to distribute the survey in Persian and English within their constituencies. Relying on random snowball sampling, we encouraged our local partners to distribute the survey to their own contacts, thereby linking us to their own personal or professional networks of budding Iranian social entrepreneurs throughout the country. In April 2015, we conducted structured and semi-structured interviews during a research trip to Iran. One of the most fascinating highlights of this trip for us was Azadeh’s participation in a workshop on social entrepreneurship in Iran. Overall, more than 100 entrepreneurs from around the country responded to our survey. Our findings suggest that this sector is growing rapidly and needs urgent support, nurturing, and scaling. Some of our most important findings are highlighted below:

Iran has an estimated social entrepreneurship market of 50,000 to 75,000 active participants.

83% of Iranian social entrepreneurs are currently engaged in an initiative, organization, or start-up with a social, economic, or environmental objective.

60% believe in the use of technology toward finding more effective solutions to their modern day challenges.

More than 50% of survey participants is actually pursuing the process of building and running a socent as part of their daily job.

Women who are heavily under-represented in our surveys have the highest participation rates in social enterprise startup events, weekends, and trainings.

The sector, although nascent and evolving, also faces obstacles that were highlighted in our survey in relation to the ecosystem; in particular, government red-tape, lack of regulation in favor of social enterprises, unavailability of foundations grants, impact investors, loans for social entrepreneurs, the unavailability of exchange programs, and opportunities to connect to regional and international social entrepreneurship knowledge networks.

Although some of the above-mentioned hurdles are not unique to Iran, the rise of social entrepreneurship has actually occurred surprisingly late in Iran compared to the rest of the region. In the aftermath of the Arab Spring, the UAE, Egypt, Jordan, and Lebanon have experienced a rise in number and quality of social enterprises. Many Middle Eastern social entrepreneurs’ ventures have scaled across the region and Northern Africa, receiving support from institutional donors, impact investors, and international foundations as well as organizations such as Ashoka, Echoing Green, and the Unreasonable Institute. Due to the international sanction regime and visa restrictions imposed on Iranians, many social entrepreneurs have not benefited from such outside support and opportunities for cross-pollination, and have rarely had a chance to access fellowships or exchange programs, or grant support. This puts them in an even more disadvantageous situation.

Yet, despite these obstacles, we found that exciting and socially innovative initiatives are emerging in the country, and entrepreneurs are adapting successful models in social entrepreneurship to the local and national conditions and needs. We present several of these initiatives in Iran that are led by visionary socents.

Tehran Hub is a nonpolitical and non affiliated organization combining a comprehensive co-working space, incubator and accelerator program and is about to get launched in partnership with Amirkabir University and Samsung. The director, Alireza Omidvar, has also served as a catalyst in drafting and preparing new national legislation submitted through Tehran Mayor’s office under the title of CSR Program for Municipalities, to officially recognize social enterprises as separate legal entities along side traditional charitable/nonprofit organization and for profit businesses, which is a unique undertaking. The Hub is targeting young social entrepreneurs in the country, and focuses using technology and social innovation to address pressing social, economic and environmental problems in the country, while building a resilient ecosystem for social entrepreneurship.

Other fantastic initiatives that we have learned about in our interactions with socents in Iran are those social entrepreneurs who are using technology and online platforms to solve social problems. For example Ladybug has boosted the participation of Iranian women in the technology and start-up world through content building, community, and educational programs.

Dastadast, supports indigenous artisans in Iran with business and capacity building solutions, and offers them an ecommerce platform to improve their livelihoods. The co-founder, Mrs. Faezeh Derakhshani, emphasizes the need for more education, access to international experiences, and knowledge platforms to boost the capabilities of Iran’s social entrepreneurs instead of emulating foreign models blindly. She states, “Many Iranian entrepreneurs develop their ideas” for example at social startup weekends, “and present them as social enterprises, but these initiatives are essentially duplicates of other initiatives, or not at all socially innovative or solving a social problem within a community.“ With regards to the use of technology and social innovation, she expresses the need for more sharing and learning about other successful social-tech models and educating the youth about the use and purpose of technology “not just to launch a website, but actually using technology in the design of a socially beneficial solution, take for example the use of solar energy providing electrification in remote rural areas.”

One of our favorite organizations is the Roozbeh Charity, based in Zanjan province, which focuses on the education and promotion of waste reduction and waste separation among citizens. The charity has a unique grassoots mobilizing and hybrid model aiming to prevent environmental pollution through waste collection, and has led to a considerable number of new jobs as well as an important source of revenue for the organization.

Mr. Najafi, who is a member of the board, believes that considerable attention is paid to social entrepreneurship at bootcamps, startup weekends, and other type of events and higher education institutions, and that “its revealing of a rising sense of consciousness within Iranian society that centers on community interests and no longer based on individualism.”

Overall, driven and passionate social entrepreneurs who have found creative solutions for their country’s social problems lead all of these organizations. The potential for (impact) investors, as well as the Iranian diaspora, to support these initiatives either through donations, or other resources, such as mentoring as well as connecting to transnational networks is unprecedented. Since Iran and the P5+1 recently reached a nuclear deal, the opportunity to collaborate with the Iranian social entrepreneurship community and empowering them to carve an effective, resilient, and strong ecosystem for social entrepreneurship has become a lucrative reality for Western and Iranian diaspora investors.

Photo Credit: Roozbeh Charity

A Wealth of Talent: Domestic and International Markets for Iranian Art

Over the last decade, the global market for contemporary Iranian art has witnessed an extraordinary surge in activity and sales. It is not simply international sales that characterize Iran’s art market. Domestic auctions have seen record prices in recent years and the secondary art market in Iran continues to grow and develop in the face of significant challenges.

Throughout the last decade, the global market for contemporary Iranian art has witnessed an extraordinary surge in activity and sales. According to an analysis by Roman Kräussl of the Centre for Financial Studies at Goethe University, drawing on data from the Blouin Art Sales Index (BASI), between 2000 and 2012, there were 3,500 significant sales of paintings across 59 global auction houses. Of these, 650 – comprising roughly 20% of the total – were of paintings by Iranian artists. Buyers in hotspots for contemporary Middle Eastern art such as London, Dubai, and Doha have been snapping up works by Iranian masters and emerging artists alike, amid the sound of the pounding gavel and the sensation of sweaty palms. Christie’s in Dubai and Sotheby’s in London remain the dominant auction houses in the market.

It is not simply international sales, however, that characterize Iran’s art market; domestic auctions have seen record prices in recent years. The June 2015 Tehran Auction saw the sale of 126 pieces, and generated over USD 7 million in sales. As such, the average sale price for this year has been roughly USD 55,000, slightly higher than the average price enjoyed by paintings from the MENA outside Iran. Looking to the BASI dataset for the years 2000-2012, 70% of Middle Eastern paintings sold at auctions were at prices below USD 50,000.

According to collector and Salman Matinfar, Director of Tehran’s Ab Anbar (lit. “Waterhouse”) art space, works by contemporary Iranian artists are currently selling for more inside the country, than in international markets, as higher domestic demand has raised prices. Matinfar believes that this demand is a result of two phenomena: first, some buyers are treating art as an alternative investment. A young businessperson quoted in the Financial Times report on the Tehran Auction noted how, “over the past 15 years, the value of real estate has risen by 25 times and gold by 45 times but art has gone up by 250 times.” He added that while “Iran’s art market is still small and traditional investors do not yet consider it a triple A asset … there is big room for growth”.

Second, and perhaps more commonly, Matinfar identifies a clear phenomenon where many of Iran’s nouveaux-riche have been investing as a means to “buy” entry into cultural and artistic circles, and gain credibility for themselves beyond their reputations as savvy entrepreneurs and businesspeople. The Tehran Auction, which has seen sales grow tenfold in the past three years, has caused controversy as observers have been debating whether the buyers are true patrons of Iran’s art economy, or simply speculators in a marketplace.

The concerns over patronage may be premature, though, as the overall market remains relatively small. While the international market for Iranian art enjoys a higher level of diversification and distribution as a whole, there are still more “serious” collectors of Iranian art (i.e. those buying works valued above USD 50,000) inside Iran than worldwide; but the key movers are few. According to artists and collectors, there are approximately 10-15 well-known collectors in Iran who dominate the market. The small number of serious collectors contributes to volatility.

As such, growth in secondary art sales, such as the growth seen in the Tehran Auction, is a step in the right direction towards the development of a larger secondary market for Iranian art, and, concomitantly, greater stability in terms of prices and demand. This year’s positive Tehran Auction gave many collectors, gallery owners, and artists cause for optimism.

While the growing secondary market may mean decreased volatility inside Iran, other developments have raised concerns. At the May 2015 Christie’s auction of modern and contemporary Iranian, Arab, and Turkish art in Dubai, works by Monir Farmanfarmaian and Rokni Haerizadeh set records. However, many noted that in comparison to previous years, and in relation to Arab artists, Iranian artists on the whole underperformed. Though some may take this “slump” at face value, others have pointed towards the rise in Arab nationalism among collectors and patrons in the Persian Gulf, and a preference on their part to invest in Arab artists, as opposed to Iranian ones. Perhaps the political forces that are contributing to optimism and growth in Iran’s domestic art market are also be causing shifts in how collectors treat Iranian artists in the context of Middle Eastern art.

Regardless of these shifts, one thing is certain: Iranian art is increasingly popular both at home and abroad; and, the recent nuclear deal reached between Iran and P5+1 countries will likely boost growth.

For example, according to Christie's Middle East Director Michael Jeha, Tehran will soon witness an influx of American buyers longing to lay their hands on hitherto inaccessible works of art. While this has yet to be witnessed, what one can expect to see in the States, for instance, is an increase in the availability of Iranian art, as well as an augmented presence of Iranian artists, who have long been unable to attend artist talks and conferences – and even their own exhibition openings – as a result of decades-long strained Iran-US relations.

Where prices for Iranian art are concerned, it would be natural to assume that they would surge worldwide as a result of increased demand. However, many dealers and gallery owners have been able to justify higher prices for works by domestic Iranian artists as a result of relative scarcity and the difficulty in sourcing pieces. Post-sanctions, a greater supply of art might actually temper rising prices. Opinions vary on the matter, and it is difficult to predict precisely what will happen in the international market for Iranian art. Yet, it is hard not to be optimistic. Given the wealth of talents on offer, Iranian artists will no doubt soon enjoy greater fortunes on—as the Persian idiom goes— “the other side of the water.”

Photo: Christie's

The Iran Deal in Wider Europe: The Case of Poland

◢ Post-sanctions trade and investment reporting has focused on three major countries: Germany, France, and Italy.

◢ But other European countries bring opportunities that should not be overlooked. A push to Iran by Poland's Economic Minister Janusz Piechociński reminds us that the story of Iran-Europe economic ties importantly extends to smaller economies as well.

The story of Iran’s anticipated economic windfall following the JCPOA Iran Deal has centered on trade and investment from three countries: Germany, France, and Italy. German Vice Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel’s recent visit to Iran will soon be followed by visits from France’s Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius and Italy’s EU High Representative Frederica Mogherini.

These visits bring with them the promise of political support for boosted trade and investment ties potentially worth billions of dollars. A recent research note from the macroeconomic team at Deutsche Bank made an upbeat assessment on the back of Gabriel’s visit:

If German exports to Iran were to rise towards their previous peak, this would correspond to an increase of EUR 2 bn. The increase could even come to EUR 4.5 bn if Iran's export share were to rise back to 0.6%. In the latter scenario, German GDP growth could be stimulated by an increase of, say, a maximum of 1/4% – spread over several years.

But while business reporting and research notes have focused on the prospects in Iran for Europe’s largest economic actors, other opportunities have gone less noticed.

Consider Poland, Europe’s 10th largest economy. This September a Polish economic trade mission led by Economic Minister Janusz Piechociński will travel to Iran. This is one of several such visits in recent years. In May, a delegation of around 100 business people traveled to Iran with Polish Deputy Foreign Minister Katarzyna Kacperczyk. The upcoming economic mission is part of a newly established “Go Iran” program devised by the Economic Ministry. Around 50 major Polish companies are expected to participate.

The visit is likely to be well-received in Iran. Poland and Iran have historically enjoyed friendly ties. In fact, they have the longest consecutive diplomatic relations between any two countries, and on March 1, 2015, celebrated their 540th anniversary of relations. Ties were strengthened through various episodes in history, including during the Second World War when over 120,000 Polish émigrés sought refuge in the ancient city of Esfahan. Some of them remained long after the war, even marrying locals. Polish tourists continue to travel to Iran in significant numbers, which itself presents a market opportunity.

Despite this shared history and cultural affinity, however, overall trade has remained meager, especially under the pressures of sanctions. Last year, Polish exports to Iran amounted to just EUR 34.9 million, while imports to Poland were valued at EUR 22.4 million. These figures are just a tiny fraction of the EUR 2 billion in exports achieved by Germany in 2013.

However, Poland and Iran should and could have much larger economic cooperation in the near future. Over the past thirty five years, many issues have limited the potential of trade between the two countries, namely the economic influence of the Soviet Union, the USSR's subsequent collapse, and Poland seeking collaboration with Western Europe and private-sector led initiatives for its growth. But with the new geopolitical realities heralded by the JCPOA agreement, new Polish-Iranian economic opportunities could come online.

In many corporations, Poland and Iran are actually part of the same operational region. This is both true when considering companies with EMEA (Europe, Middle East, Africa) divisions, and also, more specifically, for companies with CEBAME (Central Europe, Balkans, Middle East) divisions.

The countries in Central Europe and the Middle East share similar levels of development and industrialization.

Polish and Iranian officials typically mark out three sectors for collaboration when speaking of economic opportunities: agribusiness, machinery and transportation, and oil and gas.

In the area of agricultural and food and beverage exports, Iran is an attractive market with huge demand. Poland’s agricultural sector is currently undergoing a “golden age” with agri-food exports rising to USD 27 billion in 2014. Polish food brands are already familiar to many Iranians, with E. Wedel chocolates and Pudliski sauces present on Iranian shelves.

Piechociński, the Economic Minister, reacted to the July 14 JCPOA agreement by noting that the deal could be a huge opportunity for Polish agribusiness particularly in the export of poultry and beef.

But heavy industry, transportation, and oil and gas are also sectors that could see activity. Piechociński marked out the “great opportunity to sell several thousand [train] carriages, several thousand trams, subway cars.” Machinery and transportation equipment amount to 37.8% of Polish exports, valued at around USD 60 billion.

In terms of oil and gas, Iran’s value as an engery supplier was first mooted in 2008, when the Polish gad firm PGNiG signed a tentative agreement for the import of Iranian gas. At the time, Poland was seeking to wean itself off reliance from expensive and politically risky Russian supply. Sanctions ended the scope for collaboration, but prior to the July agreement, PGNiG announced it was interested in picking up its operations in Iran again, with plans to open an office for to scope possible joint ventures.

The case of Poland reminds us that post-JCPOA economic opportunities will not be limited to major economies like Germany, France, and Italy. Smaller European countries may enjoy special advantages in being able to focus high-level political and economic resources behind trade and investment development plans. Iran clearly has many "suitors" as senior political and business delegations are expected in Iran. The question remains whether the Iranian authorities and business community will be able to coordinate activities on their end to make sure economic opportunities can be realized.

Photo Credit: Meghdad Madadi, Tasnim News Agency

Sanctions at Dusk: The Impact of JCPOA on Iran's Private Banks

◢ The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action— a document of comprised of 159 pages, negotiated over 23 months—represents a triumph of diplomacy.

◢ Sanctions relief will be operationally challenging. Will this relief lead to investment in the Iranian banks themselves?

The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action— a document comprised of 159 pages, negotiated over 23 months—represents a triumph of diplomacy. It also represents one of the most important single documents ever drafted for Iran’s economy.

The first attachment of the second annex lists the various Iranian entities which can expect to receive tangible sanctions relief beginning on the so-called “Implementation Day,” or the day that the IAEA verifies that Iran has successfully completed the measures required for the curtailment of its nuclear program. Most experts expect implementation to take about six months, which, in the scheme of nearly a decade of biting sanctions, seems imminent.

Sanctions relief will be operationally significant and allow free and unencumbered transfer of funds to and from Iran, the development of correspondent banking relationships, the facilitation of trade finance, and the reopening of offices and subsidiaries in Europe.

Many banks will even earn bank access to SWIFT, although those that are designated under US Iran Transactions and Sanctions Regulations (ITSR) on the Specially Designated Nationals (SDN) list will only have assured access to SWIFT after “Transition Day,” which can occur as soon as the “Director General of the IAEA submits a report stating that the IAEA has reached the Broader Conclusion that all nuclear material in Iran remains in peaceful activities.” As such, several major banks will be to wage independent campaigns to be delisted in order to gain access to SWIFT.

Even without such financial messaging services, the range of revenue-generating activities within Iran’s banking sector is set to expand. Yet, while the range of operations will expand, it is unclear to what extent Iranian banks will become more attractive targets for investment.

Looking to specific banks that are set to benefit from the JCPOA, the private banks listed on the Tehran Stock Exchange deserve particular mention. These include Eghtesad Novin (EN) Bank, Karafarin Bank, Khavarmianeh (Middle East) Bank, Mellat Bank Pasargad Bank, and Parsian Bank.

Mellat, Eghtesad Novin, Parsian, and Pasargad Bank rank among the 30 largest companies on the TSE measured by market capitalization, and when accounting for Khavarmianeh and Karafarin Banks, the total market capitalization of these firms approaches USD $10 billion.

With a wider range of banking activities available, these companies will become more attractive investment targets for individuals and institutional investors within Iran. Therefore, we should expect Iran’s banking sector to grow as a percentage of the overall economy in the next 1-2 years as domestic investment drives growth and rising valuations.

However, it is unclear if foreign investors will be among those to invest in Iranian banks. A research note from Renaissance Capital predicts that Iran will see “$1 billion of inflows to equities within a year of sanctions ending” from foreign investors, and overall “portfolio flows could be significant as early as 2016.” However, although Global Chief Economist Charles Robertson, expects, “investors to explore opportunities ahead of time, find custodians and earmark key stocks to buy” he doubts that these target stocks “will include many banks.”