In Iran, ‘Ordinary Women’ Lead an Extraordinary Movement

One year has passed since the tragic death of Mahsa (Jina) Amini in police custody and the start of the Woman, Life, Freedom movement, which has induced cultural transformations within society and families in Iran.

One year has passed since the tragic death of Mahsa (Jina) Amini in police custody, the event that ignited the Woman, Life, Freedom movement. This movement has provided a platform for acknowledging the enduring struggles of ordinary women in Iran, a battle that had been ongoing long before September 16, 2022. By “ordinary women,” I refer to individuals outside the elite and activist spectrum, adapting from sociologist Asef Bayat’s definition of “ordinary people” in his book Revolutionary Life. The struggles of ordinary women in Iran were often ignored or sidelined until last year. While I respect the efforts of all women’s rights activists dedicated to improving women’s rights in Iran, I believe the “Mahsa movement” stands on the shoulders of ordinary women, many of whom may not belong to the middle class or possess feminist knowledge, but who are undeniably fighting for the freedom to lead ordinary lives.

The Woman, Life, Freedom movement has induced cultural transformations within society and families in Iran. Many parents who previously advised their daughters to accept the mandatory hijab as a “minor issue” have now thrown their support behind their daughters’ quest for freedom of choice. The presence of women with uncovered hair has become more widely accepted. Women feel safer going out without the hijab. As one woman told me, “before the Woman, Life, Freedom movement, when I went out without hijab, I felt I was breaking social norms and that I was doing something weird in the eyes of society. But now I feel safe and know if somebody scolds me about the hijab, other people in the streets will come to protect me.’’ These cultural changes in the Iranian society are not limited to the hijab issue. The status of women within families has largely changed, and more women are gaining autonomy.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the Mahsa movement is the newfound overt support from men. Women have historically borne the brunt of struggles against a patriarchal society and state, but the Mahsa movement marks a turning point where men have joined in supporting women’s causes. Whether this support will extend to other women’s issues, such as unequal inheritance and divorce laws, remains to be seen.

The Woman, Life, Freedom movement has also significantly transformed the subjectivity of ordinary women. It has united women with shared experiences and pain, reminding them that they are not alone. While there have always been small support networks among women, this movement has elevated this solidarity to a national (and international) scale. In one instance, I saw a police officer who wanted to confiscate a vendor’s goods in the Tehran subway. Women inside the wagon rushed to save the vendor, pulling her and her goods inside. The collective struggle to reclaim public spaces has emboldened women, many of whom now proclaim, “I have become braver.”

But the Mahsa movement has not been limited to women’s rights alone. The movement initially protested against mandatory hijab but, like an umbrella, it now encompasses a range of other issues in Iran, including the unbearable economic challenges and ethnic and religious discrimination. Protesters have also been calling for the overthrow of the Islamic Republic. Yet, the state’s brutal suppression of these protests underscores the complexity of achieving political goals such as regime change. According to Jack Goldstone, a scholar of social movements, the Mahsa movement continues to lack some of the key factors needed for a full-scale revolution, such as an organised programme and the involvement of older generations.

The conflict between Iranian authorities and Iranian women dates back to the establishment of the Islamic Republic in 1979, when women’s rights were among the first to be compromised. Women did come to the streets to protest against the enactment of the compulsory hijab law and abrogation of the family protection law in March 1979—but the state prevailed in curtailing women’s rights. Four decades later, despite various policies, ideological education, and unequal laws aimed at curbing their economic, social, and political opportunities, Iranian girls and women are trying to break free from traditional gender roles.

What is undeniable today is the Iranian women’s desire for both “freedom” and an “ordinary life.” These two desires resonate strongly in my conversations with many Iranian women from around the country. Iranian women have made strides in education despite numerous obstacles. They are rising against gender-based oppression and have exhibited remarkable resilience in their quest. However, their economic participation remains disproportionately low, forcing many into the informal economy. Women are also denied the right to run for president, and the majority are disqualified to run for public office.

The Iranian state has persistently attempted to exclude women from various spheres, yet they persist in resisting. They aspire to careers as diverse as football referees, aerospace engineers, mathematicians, musicians, and much more. The evolving lifestyle of ordinary women highlights the failure of the Islamic Republic’s discourse in imposing gender roles. Their fight for the freedom to choose how they dress is just one aspect of the broader rights they seek. According to political scientist Fatemeh Sadeghi, the actions of Iranian women are not rooted in anger. Rather, they represent the transformation of anger into a force for change. Accordingly, political change, in their view, will emerge from social empowerment. These women are, in essence, revolutionaries without a revolution. They do not want to achieve freedom through revolution. They aim to achieve revolution through freedom.

Photo: Rouzbeh Fouladi

How Shifts on Instagram Drove Iran's 'Mahsa Moment'

Iranians are using Instagram for political activism like never before. But these changes were not sudden. The “Mahsa Moment” was driven by user trends on social media that have been years in the making.

This article was originally published in Persian.

In a narrative crafted by various political and intellectual currents, the “Iranian Instagram” is often presented as a means of depoliticising the attitudes and behaviours of the Iranian people, with its users engaging in vulgar content, falling for false news and claims, cursing at famous figures, and morbidly posting accounts of the more attractive sides of their daily lives. This same formulation is used by the conservative movement (also called the Principalists movement) to realise their policy of "organisation" and "protection" of the Internet. Using comparable language, pro-change political currents also direct users to ostensibly more political platforms, such as Twitter and Clubhouse. However, if this is the case, why has Instagram become one of the most prominent platforms for expressing and even organising political protests in the “Mahsa Moment?”

The simplest and shortest response to this question is to attribute everything that has occurred over the past two to three months to the Islamic Republic's enemies. This response has been heard repeatedly on official domestic media in recent months. Some of the self-proclaimed leaders of the people's protests in the media outside of Iran have given the same answer in different words, claiming that these events are the result of their years of hard work and meticulous planning. This type of analysis of people's collective actions is not only unenlightening and ineffectual but is a significant contributor to the current crisis.

However, another approach might be to temporarily set aside preconceived notions about online social networks in favour of a more empirically grounded and scientifically sound approach to answering this question. A portion of the answer to this question can be found by analysing the changing trends on Iranian Instagram.

Those of you who have been following along for the past three years may recall that I began a longitudinal study of Iranian Instagram in 2019 and have since published an analytical update three times in the early fall of 2019, 2020, and 2021. This year, data collection and analysis took longer than usual due to Internet filtering and interruptions, delaying the report preparation for the fourth phase of this research.

With these explanations, the findings of the fourth consecutive year of this research will be presented within the context of the question posed at the beginning of the report. The findings of this study demonstrate that the transformation of the Iranian Instagram space at the “Mahsa Moment” into a platform for online protests and the organisation of offline protests cannot be attributed to a pre-planned project. Rather, we must understand and analyse this phenomenon in light of the agency of users and the gradual changes that have occurred on Instagram in Iran over the past few years. In addition, despite tightening restrictions over the past year, Iranian Instagram continues on its path, both quantitatively and qualitatively, consistent with the previously optimistic changes.

Figure 1 depicts the frequency of active popular Iranian Instagram pages between 2019 and 2022. Despite the tightening of various restrictions facing Iranian users on Instagram, the number of active Iranian pages on Instagram with more than 500,000 followers increased by 17% in 2022, reaching 2,654.

Figure 1: Frequency of active Iranian Instagram pages with over 500k followers from 2019 to 2022

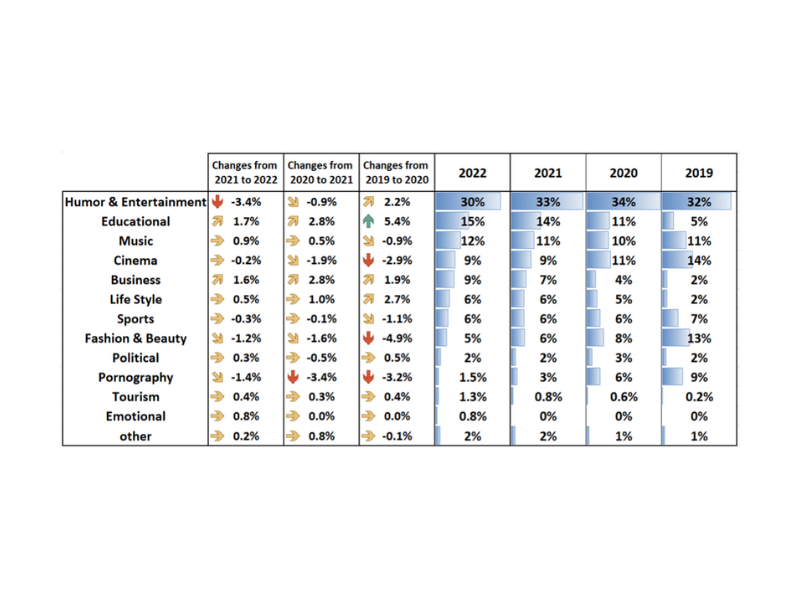

As displayed in Table 1, the share of "humour and entertainment", "fashion and beauty", and "pornography" pages among the most popular Iranian Instagram pages has decreased significantly over the past year. While the decline in "fashion and beauty" and "pornography" pages continues a longer trend, the declining ratio of "humour and entertainment" pages on Iranian Instagram over the past year is something new. In contrast, the percentage of "educational" and "business" Instagram pages has continued to rise in 2022.

The appearance of "tourism" and "emotional" pages on popular Iranian Instagram pages in 2022 is another notable change. On the tourism pages, content pertaining to tourism in various regions of Iran and the world is published, whereas, on the emotional pages, content that represents human feelings and emotions are published.

Table 1: Share of popular pages by primary subject from 2019 to 2022

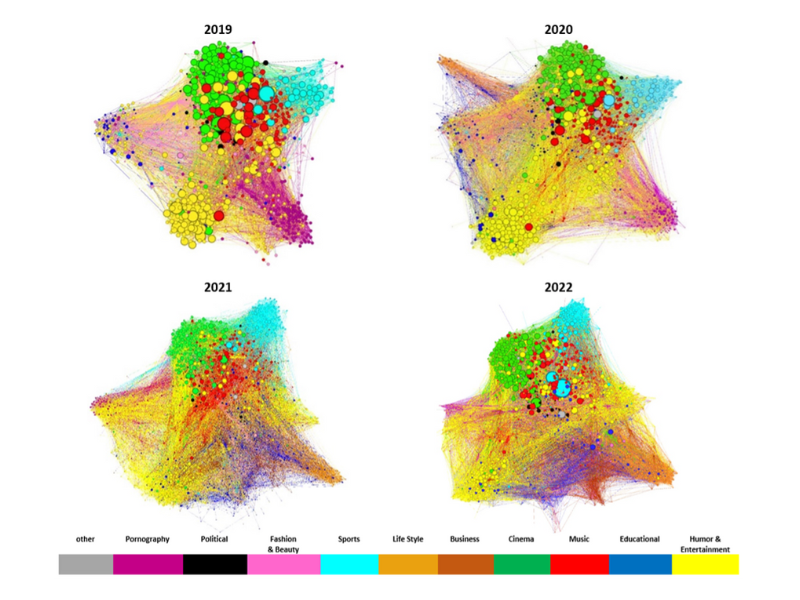

The trend of changes in the network of relationships between popular Iranian Instagram pages is illustrated in Figure 2 using the Indegree Index. When comparing the changing trend of the graphs from 2019 to 2022, we observe that education (dark blue), business (brown), lifestyle (orange), and fashion and beauty (pink) pages have become increasingly integrated within their respective fields and have distanced themselves from other fields. In the upper portion of the graphs, from 2019 to 2022, we notice an increase in the intertwining of sports screens (pale blue), movies (green), and music (red). In other words, these three types of popular accounts—also known as "celebrity” accounts—have gradually shaped a field that is related to issues outside of their profession. In this multifaceted field, in addition to celebrity pages, there are humour, entertainment, political, and social pages (yellow, black, and grey).

Figure 2: Changes in the network of relationships between popular Iranian Instagram pages from 2019 to 2022, as measured by the Indegree Index

Figure 3 displays the ten Iranian Instagram influencers with the highest authority based on the Authority index. All of these individuals belong to one of the three categories: sports, film, or music. These three categories also overlap. Moreover, with the exception of two individuals, the rest post additional content on the page related to their audience's political, economic, and social concerns and demands, as well as their profession and area of expertise. Let us refer to this type of celebrity as a "celebrity-activist.”

By a significant margin, Ali Karimi has the highest authority among the most popular Iranian Instagram pages, followed by Ali Daei, Golshifteh Farahani, Javad Ezzati, Amir Jafari, Bahram Afshari, Mahnaz Afshar, Majid Salehi, Parviz Parastui, and Reza Sadeghi.

Figure 3: Network relations between popular Iranian Instagram pages in 2022, as per the Authority Index

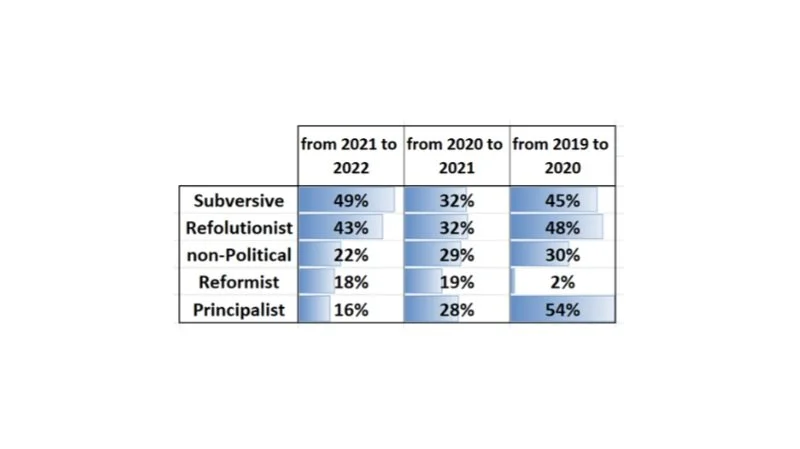

By reflecting on Table 2 and reviewing Table 1, we can gain a greater appreciation for the reasons why celebrity-activists on Iranian Instagram gain authority. Table 2 demonstrates that the number of followers of popular subversive pages has increased by 49% over the past year. This index was 43% for refolutionist (neither revolutionist nor reformist), 22% for non-politicals, 18% for reformists, and 16% for conservatives (Principalists). Comparing these statistics to those from previous years reveals that the notion of protesting the current political situation has become increasingly popular and a sought-after item on Iranian Instagram over the past year.

In contrast, as shown in Table 1, the proportion of political pages (individuals, groups, or organisations professionally engaged in political activity) among the most popular Iranian Instagram pages did not change significantly between 2019 and 2022, fluctuating by approximately 2%. In other words, Iranian political professionals of various political orientations lack the capacity and acceptance to represent the nation's political attitudes and demands. Iranian Instagram users have increased pressure on other popular Iranian Instagram pages, requesting that they reflect and even represent the political protests of the Iranian people. As previously explained, education, business, lifestyle, and fashion and beauty pages have not directly engaged with this demand of users due to professional considerations; however, a substantial portion of the movie, sports, and music pages have responded positively to the demand of their followers, largely due to their professional considerations. In actuality, it is the crisis of political representation that has placed celebrities in the position of representing the political demands of the Iranian people and given rise to the phenomenon of "celebrity-activists.”

In this sense, these are the people who have agency and have utilised the smallest opportunities to protest the status quo. In this way, they also take advantage of the opportunities provided by celebrities. In such a scenario, political professionals dissatisfied with the formation of these relationships between users and celebrities alter the truth and promote the narrative that "these excited people" have been duped by "illiterate celebrities!" Almost every political faction has employed such insults on occasion. Of course, these same "illiterate celebrities,” once defended participating in elections and voting for reformists, thereby increasing voter turnout. But, at the current time when celebrities are under the pressure of users and the online space has aligned with the Mahsa movement, conservatives and a significant portion of reformers assert that "the excited people" have been duped by the celebrities they follow. In actuality, instead of taking fundamental and principled measures to address the escalating crisis of political representation, political professionals sometimes align themselves with "concerned artists and athletes" and "intelligent people" and sometimes curse "illiterate celebrities" and "excited people" in accordance with their immediate interests.

Table 2: The rise in followers of popular Iranian Instagram pages by political orientation from 2019 to 2022

The relationship between Instagram users and popular pages has gradually developed an inherent logic over time, which can be made more tangible by examining a few examples from Table 3. Hassan Reyvandi's number of followers increased by more than 6 million between 2019 and 2020, when, in addition to political protest, the production of humour and entertainment content independent of official media was considered a high-demand commodity on Instagram. Consequently, he moved from third place in 2019 to first place in 2020. From 2020 to 2021, when humorous content independent of the official media still had some appeal, Reyvandi maintained his position by keeping a considerable distance from other prominent pages. Nonetheless, Reyvandi's position has been weakened over the past year, when "opposition to the existing political conditions" became the high-demand commodity on Iranian Instagram. Indeed, it is highly probable that he will soon be demoted. Rambod Javan has already experienced this fall. After failing to meet the expectations of political dissidents on Instagram, he dropped from the second most popular Iranian Instagram page in 2018 to the tenth most popular in 2019. Behnoosh Bakhtiari's position declined even further. Bakhtiari, who had the fourth most popular Iranian Instagram page in 2019, was harshly criticised by many Instagram users after taking several controversial positions, including publishing an Instagram post against the three protesters of November 2019 who were sentenced to execution. As a result, her page fell from the fourth most popular Iranian Instagram page to the nineteenth position within three years. Such evidence demonstrates that, contrary to the misleading term "influencer,” the resultant of the collective will of users has a substantially more direct and significant effect on the behaviour of influencers, not the reverse.

Table 3: Follower counts of the most popular Iranian pages from 2019 to 2022, per million users

From 2019 to 2021, the percentage of female Instagram celebrities in Iran rose from 32% to 42%. However, there has been no discernible change in the gender distribution of famous people over the past year. Likewise, while the percentage of popular pages based in Iran increased from 76% to 81% between 2019 and 2021, there has been no significant change in this regard over the past year.

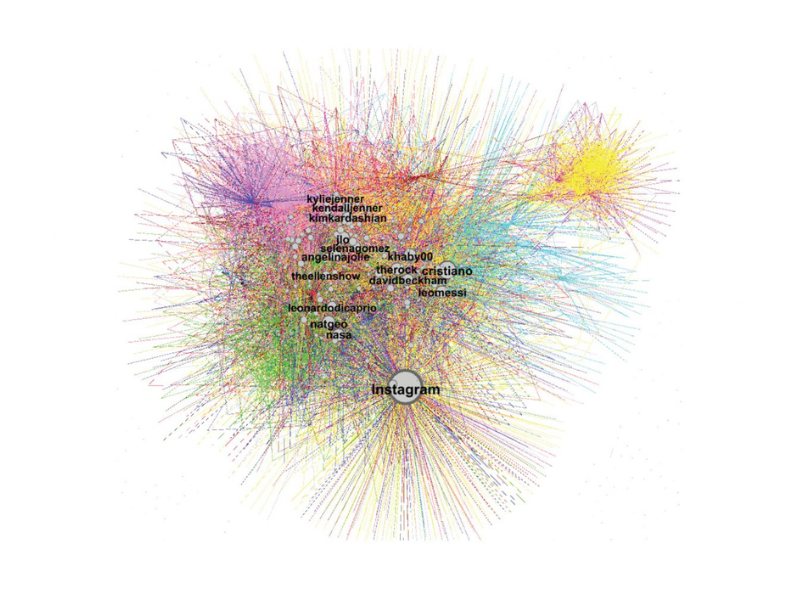

Let us conclude by examining the influence network of popular Iranian pages as affected by global authority pages. Based on the Authority Index, none of the foreign pages with high authority among the most popular Iranian Instagram pages are political. NASA, National Geographic, Leonardo DiCaprio, and Ellen DeGeneres have the most authority among film-oriented pages. Kylie Jenner, Kendall Jenner, and Kim Kardashian have the strongest authority among fashion and beauty pages. Jennifer Lopez, Selena Gomez, and Angelina Jolie have the highest authority jointly among the cinema and fashion and beauty pages. Moreover, Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo have the greatest authority among sports pages, while Khaby Lame, Dwayne Douglas Johnson, David Beckham, and the official Instagram page are authoritative among various sections of popular Iranian Instagram pages.

Figure 4: The position of authoritative international pages among popular Iranian pages on Instagram based on the Authority Index

Today, and particularly in the post-Mahsa era, the events that occur within the framework of online social networks are increasingly scrutinised by various political currents. Analysts with differing political leanings are discussing the relationship between online social networks and the collective protest actions of the Iranian people more than ever before. However, a quantitative increase in the analysis of online social networks can be considered a positive event if these analyses are continuously reviewed in conjunction with research findings in this field. Otherwise, it will not only be unenlightening but will also lead to the propagation of false stereotypes and, as a result, incorrect decisions and policies regarding this relatively new phenomenon.

Users' actions on online social networks may be correct in some cases but incorrect in others. It is crucial that whenever we find the actions of users to be inappropriate, we avoid blindly attributing everything to intelligent services, media, think tanks, or opportunistic and deceitful people. Instead of believing in these conspiracy theories, we should seek a more accurate understanding of the logic behind their actions and decisions using different methods and the logic of the situation in which users find themselves.

This methodological and analytic error is not unique to supporters of the government but is frequently committed by pro-change political currents when they encounter unpleasant phenomena in online social networks. In recent years, as a result of such a circumstance, many activists, analysts, and even some sociologists have shifted their focus from the lower levels of politics to security issues and have become experts on security issues and whistleblowers of media conspiracies and enemy think tanks.

The narrative of "excited and gullible users" is one of the recurring stereotypes regarding online social networks. In this narrative, social network users are uneducated and naive individuals who are constantly exploited by deceptive and opportunistic individuals, groups, and organisations. Throughout the past few years, and especially in the last few months, a great deal of commentary on Iranian Instagram has been based on this narrative. Interestingly, proponents of this narrative rarely question the veracity of this view and appear to see no need for scientific evidence to verify its veracity.

The results of the fourth phase of the longitudinal research I have conducted on Iranian Instagram users demonstrate conclusively that this narrative is highly misleading. Indeed, when criticising a false stereotype, we must take care not to fall into another false stereotype. Consequently, I hope that the caution that I have attempted to observe in writing this research report will be noted by the readers and that the research findings will be interpreted with the same caution.

Photo: IRNA

As Protests Continue, Biden Should Enable Remittance Transfers to Iran

The Biden administration should adjust its sanctions policies to authorise remittance transfers to Iran, making it possible for Iranians in the diaspora to support their family members in ways that strengthen capacities for political participation.

Protests in Iran are continuing as the Iranian people bravely maintain a presence in the streets and on social media. So far, Iranian authorities have given no clear indication that they will reform policies in line with protest demands and have signalled that a larger crackdown may be coming.

While the protests have meaningfully shifted the political discourse around women’s rights and state repression, it is unclear whether Iran’s civil society has the resources necessary to generate a large and lasting protest movement that maintains pressure on Iranian authorities and raises the costs of further crackdowns. One critical factor is the economic disempowerment of Iranian society over the last decade.

Between 2010 and 2020, the spending power of the average Iranian household has fallen by just over 20%. This loss of economic welfare is primarily the result of U.S. sanctions, particularly those imposed in 2012 and re-imposed in 2018. In the two decades leading up to 2012, Iranian households enjoyed an unbroken period in which living standards were rising.

U.S. sanctions policy has made protests in Iran more frequent, but also less likely to succeed. The economic precarity that has become a dominant feature of the Iranian social condition over the last decade makes it harder to sustain protest movements. Many Iranians literally cannot afford to organise and mobilise over weeks and months. Workers are reluctant to strike given the risk of losing their jobs. Even those who retain the economic means to protest lack the tools to organise.

In institutional terms, sanctions have weakened the formal and informal civil society organisations that help mobilise the middle class and channel middle class resources towards political action. Charities, advocacy groups, legal aid providers are starved of resources. Civic-minded women, who are at the forefront of Iran’s new protest movement, have been hit especially hard. As one Iranian activist put it last year, “Activists are struggling to survive… If they do end up with a bit of time at the end of the day for their activism, they are often too exhausted and preoccupied with economic survival to be effective.”

The recent protests have no doubt energised a wide range of social groups in Iran, but looking in both economic and institutional terms, the balance of power between Iranian state and Iranian society has clearly shifted in the state’s favour. Mobilisations have become more frequent, but they tend to be smaller and more fleeting, making it easier for the state to either crackdown or to simply wait out the protests.

As such, the Biden administration should adjust its sanctions policies to broadly authorise remittance transfers to Iran, making it possible for Iranians in the diaspora to support family and friends in ways that reduced economic hardship and strengthen capacities for political participation.

Remittance flows are restricted because banks and money transfer companies do not facilitate transfers to Iran owing to sanctions on the Iranian financial system. Most remittances are therefore made via exchange bureaus (known to Iranians as sarafis) or are hand-carried into Iran by individuals. U.S. persons are explicitly authorised to hand-carry personal remittances but are not permitted to use money service businesses. The financial flows made through exchange bureaus and hand-carry channels are difficult to track and so the true extent of remittance flows may not be reflected in authoritative estimates, but Iran is likely receiving far less remittance transfers than countries with similar economic characteristics.

The World Bank estimates Iran received $1.3 billion of remittances in 2021, equivalent to just one-tenth of a percent of GDP. By comparison, Thailand, a country with a higher per capita GDP ($19,000 vs. $16,000 in PPP terms) and a smaller population (70 million vs. 84 million), received $9.0 billion of remittances, equivalent to 1.8 percent of GDP.

It is unlikely that exchange bureaus and physical transfers total in the many billions of dollars. In short, Iran’s remittances inflows are much lower than expected given the size of the economy and the economic needs of the population. Remittances flows are far too limited to shore the economic welfare of households in the face of the generalised economic crisis to which sectoral sanctions contribute—a fact evidenced by the erosion of household consumption over the last decade.

A significant body of academic research suggests that remittances encourage political participation, including in protests. In a 2017 paper, Malcolm Easton and Gabriella Montinola use individual-level data from Latin America to explore the relationship between the receipt of remittances and political participation. They find that “remittance recipients are more likely to select protest rather than the base response” whether in a democracy or autocracy. Additionally, in autocracies, remittances make political change seem more achievable. Easton and Montinola explain that “receiving remittances increases the odds of selecting protest relative to believing change is not possible by 34%.” Abel Escriba-Folch, Covadonga Meseguer, and Joseph Wright arrive at a similar conclusion in their 2018 study which used individual-level data from eight African countries. They find strong evidence that “remittances increase protest by augmenting the resources available to political opponents” and “remittances may thus help advance political change.”

The Iranian diaspora in the United States is the largest and most politically active in the world. As U.S. persons, members of the diaspora living in the United States are unable to send remittances to Iran beyond the hand-carry method, which is not an option for those who cannot travel to Iran for personal or political reasons, or who are opting not to travel to Iran due to the increased risks facing dual nationals. To provide routine and reliable financial support to family and friends in Iran, members of the Iranian diaspora should be able to avail themselves of money service businesses or other payments solutions.

The relevant regulation does stipulate that remittance transfers “processed by a United States depository institution or a United States registered broker or dealer in securities” are authorised. However, there is a lack of such institutions offering remittance services for Iran—U.S. banks do not maintain correspondent accounts at Iranian financial institutions. As such, the Biden administration should update its regulations to enable U.S. persons to make remittances transfers through other channels. This can be done through the issuance of a new general license with two aims.

First, the Biden administration could authorise the use by U.S. persons of money service businesses, such as Europe-based exchange bureaus, to transfer non-commercial, personal remittances to Iran. Second, and perhaps more usefully, the Biden administration could authorise the use by U.S. persons of cryptocurrency exchanges to purchase USDC stablecoins and transfer those stablecoins as non-commercial, personal remittances to Iran. The administration would also need to authorise U.S. cryptocurrency exchanges to onboard users in Iran.

Exchange bureaus can typically make deposits to accounts at Iranian financial institutions. The existing regulations do state that U.S. banks can engage with money service businesses in third-countries to make remittance transfers to Iran. But that makes such transfers subject to the discretion of U.S. banks. The guidance should be modified such that U.S. persons can directly engage exchange bureaus, for example those in Europe, to make transfers to Iranian bank accounts. Making it possible for U.S. persons to use third-country money service businesses would have an immediate impact on the volume of remittances sent to Iran. However, this channel cannot scale indefinitely as money service businesses generally need to balance inflows and outflows to make transfers in a netting process.

The use of cryptocurrency could be even more impactful. While few Iranians maintain cryptocurrency accounts, the technology provides one of the few scalable options for enabling U.S. persons to make remittance transfers to Iran. So long as cryptocurrency exchanges receive guidance that allows them to onboard Iranian users, Iranians can be expected to adopt the technology and U.S. persons will be able to transfer cryptocurrency without a constraint on scale.

The authorisation should be limited to exchanges and should not cover transfers made directly to addresses or via wallet providers, because of the additional controls that the exchange can impose. It is technically feasible for cryptocurrency exchanges (such as Coinbase and FTX) to limit the value of transfers that can be received and held by Iranian users in line with the provisions of the authorisation. Additionally, transactions processed by the exchange do not happen on cryptocurrency blockchains, they are run within the exchange’s internal database. This enables the exchange to freeze any account held by its user and block further transfers if necessary. Moreover, the exchange could ensure that users were only able to transfer certain cryptocurrencies to Iran, such as traceable USD stablecoins which are pegged to the dollar (the best option is USDC, which has a track record of cooperation with US regulators). This would ensure that exchanges are not providing a platform for speculative trading by Iranian users and that Iranians do not have a perverse incentive to hold onto their remittances. These exchanges can also require additional KYC for U.S. persons and Iranian individuals on either end of a given transfer.

To be effective, these authorisations would need to be followed by extensive outreach by the U.S. Department of Treasury and U.S. Department of State to ensure that money service businesses and cryptocurrency exchanges begin supporting Iran-related transfers. U.S. authorities would also impress the importance of monitoring for suspicious transactions and could ask for data on the remittance flows to enable better enforcement. Any authorisation could be granted based on a limit to the value of remittances made by a U.S. person each month—a limit as low as a few hundred U.S. dollars could make a significant difference in supporting basic household welfare in Iran.

There is a risk of abuse by individuals seeking to transfer funds to designated entities or individuals in Iran. But the risk is limited. Flows of USDC cannot be directly taxed or expropriated by the state. To spend any remittances they have received, Iranians would either need to pay for goods and services by transferring USDC to another Iranian user that has created an account on the exchange, or by finding an Iranian user who is willing to exchange USDC for cash.

The lack of hard currency flows means that the proposed action does not entail a substantive change to the structure of U.S. sanctions on Iranian economic sectors and state-owned and controlled entities. Even so, the authorisations can significantly boost the economic resources of Iranian civil society and enable more robust political participation, including in protests. However, the decision to participate in the protests lies with each Iranian. Unlike a strike fund, this policy does not create an incentive for protest, nor are the remittances made contingent on certain kinds of political action.

There is a precedent for this approach. Even while adding sanctions on the Maduro government, the Trump and Biden administrations have notably allowed Venezuelans to continue to use U.S.-based financial services, such as the payments app Zelle, to send and receive U.S. dollars. This has had the effect of shielding many Venezuelans from even steeper declines in economic welfare as the country experienced a steep sanctions-induced recession.

Enabling Iranian-Americans to make remittance transfers to their family members in Iran within the context of existing sanctions regulations would mean that the Biden administration is not only seeking to deprive the Iranian state of resources for repression but is also working actively to preserve the power of the civil society at a time of general economic crisis. This is what true solidarity would look like.

Photo: IRNA

Iranian Women are Colliding with the Iranian State

Iranian women, supported by the many men who have now joined them, are challenging the discrimination they have experienced for decades.

On the day that Ebrahim Raisi, Iran’s President, was giving a speech at the United Nations headquarters in New York about the double standards with which human rights are pursued around the world, a tear gas canister flew past me and hit a car that was parked a few metres away. I was among the protesters running down Palestine Street in the centre of Tehran, and the tear gas was being fired directly at us by anti-riot police. We were doing nothing more than shouting slogans, but any of us could have been severely injured or killed—this was not an isolated incident. According to human rights groups, more than 90 people have been killed in the ongoing protests across Iran. The protests were ignited by the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini while she was in the custody of the morality police. The authorities have responded to these protests with a brutal crackdown—beating, shooting, arresting—and an internet blackout that has blocked access to platforms such as WhatsApp and Instagram.

Twenty years ago, it would have been hard to imagine that dozens of cities in Iran would erupt in protests against imposed religious rules. The death of Zahara Bani Yaghuob, an Iranian medical doctor arrested by authorities in Hamedan in 2007, did not lead to widespread protests at the time. But the Iranian state is reaping what they have unintentionally sown. Despite rolling back some women’s rights, such as the Family Protection Law introduced under Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, and imposing an Islamic dress code, after the revolution, a so-called Islamic educational system helped more women in rural and lower social classes to receive an education. While women in upper and middle social classes benefited from progressive laws prior to the revolution, traditional families, typically from disadvantaged backgrounds, felt more comfortable sending their daughters to school under Islamic laws. Today, women account for 60 percent of university students in Iran. It is no coincidence that Generation Z, now on the frontlines of the recent protests, are the children of Iran’s 1980s baby boomers. Generation Z’s parents were the first cohort to see a dramatic shift in the numbers of women receiving higher education in Iran.

A few hours before the tear gas canister nearly struck me on Palestine Street, I was passing security forces on Revolution Avenue when a man in plain clothes and a helmet came up to me and said, “Our cameras will capture your face. If I see you again in this area, you’ll get arrested.” “For what crime?” I asked. “No offence required,” he replied, “I have the power, and I’ll use it against you.”

The man’s boast is the key to understanding the recent protests in Iran. After Sepideh Rashnoo was harassed on a bus by a fellow citizen over her “improper” hijab in July, the dangerous power that had been delegated to pro-regime citizens became clearer. Iranians watched Rashnoo, a writer and artist, make a humiliating forced “confession” on national TV. In contrast to Rashnoo’s humiliation, the woman who harassed her over her hijab enjoyed a kind of authority bestowed upon her by the government.

Along with the morality police, the citizens who have been granted this authority stepped up their policing of the hijab rules since Raisi’s election, which was marred by record low turnout. The death of Mahsa Amini while in police custody has revealed the conflict between the Iranian government and citizens who do not want to comply with rules they believe infringe on their civil rights. There is significant disillusionment and profound doubt about the prospects of reforming a system that has shown zero interest in compromise. If the Green Movement’s slogans were full of verses from Qur’an and other Islamic references, the slogans heard in the recent protests contain no Islamic references and no requests for narrow reforms.

Despite the economic stagnation, systematic corruption, and mismanagement in recent years, economic grievances do not feature in the slogans either. The protests have coalesced around dissatisfaction about how the Iranian state relates to society. The protests that erupted after Mahsa Amini’s death emerged mainly from marginalised groups: Kurds who are an ethnic minority, the middle class which as encountered so much hostility from the government, women who are not even recognised or protected in the system if not wearing a hijab, and the working class who have witnessed widespread governmental corruption in the recent years.

While living under the strict rules of an increasingly authoritarian state, the future for these oppressed groups is grim—they see a dead end. Accordingly, for the Iranian authorities, the unification of these various social groups, which has happened for the first time since the 1979 revolution, poses a new challenge.

In recent years, Iran’s middle class has been shrinking because of international sanctions and economic decline. Still, they have had some spaces, such as social media and satellite television, to engage with progressive ideas on human rights. Long before the recent protests forced Iran’s national television to address the issue of compulsory hijab on their programmes, subjects such as the hijab, personal freedom, and gender politics have been debated on social media and foreign-based television channels before large audiences. In this way, two different worlds have coexisted and one is now crashing into the other.

Are we witnessing another revolution in Iran? It is hard to ascertain. Iran’s state ideology still has sincere supporters, not just at home but also across the region. Some analysts have pointed to the limited number of protesters to suggest the protests are a “virtual revolution” that exists only on social media. Still, a revolutionary turn does not necessarily depend on the number of active protesters; it arises from a dead-end situation. Following Ayatollah Khamenei’s speech in which he called the protests “riots” and blamed a foreign plot for the unrest, the obstruction has never been clearer.

Nevertheless, there is a movement in Iran. Motivated by their anger following Mahsa Amini’s death, a growing number of women who have found the courage to go out with their hair uncovered in public. For a political system that places enormous emphasis on women’s appearance, this is a profound form of protest. Iranian women, supported by the many men who have now joined them, are challenging the discrimination they have experienced for decades. They have already achieved a great victory by making their voice heard around the world.

Photo: EPA-EFE

Grief and Grievance in Iran’s Growing Protests

For four days, protestors have been in Iranian streets. Iran has seen multiple waves of unrest in recent years. But this time, the protests seem different.

For four days, protestors have marched on Iranian streets. The protests were triggered by the killing of Mahsa Amini, who was fatally injured while in the custody of the Guidance Patrol, a police unit in Iran that mainly enforces the country’s Islamic dress code. Amini, who was 22 years old, died last Friday after several days in a coma. She was visiting Tehran from the province of Kurdistan to see her relatives.

Iran has seen multiple waves of protests in recent years. In 2017, protests erupted in response to a sharp drop in the value of the rial and grew to include claims of economic mismanagement and corruption. In 2019, nationwide protests were triggered by a fuel subsidy reform and Iranians took to the streets to decry declining living standards. In 2021, protests focused on water rights recurred in various Iranian provinces. This year, labour protests have taken place across the country as a public sector employees and blue-collar workers seek job security and wage increases.

In many respects these protests have been linked. In each round of unrest, protestors mobilised because of similar grievances, mainly economic. They shouted the same slogans—“Death to the dictator!”—expressing anger at a sclerotic political establishment. They faced the same brutal response from security forces, who injured and killed with impunity.

But the protests triggered by the killing of Mahsa Amini appear different and are arguably more significant. While there are similarities with previous protests when considering the grievances, the slogans, and the repression, there is something distinct about the emotions being foregrounded as the mobilisations take place.

So far, people of different backgrounds and different classes have joined these protests. They have taken to the streets of Amini’s hometown of Saghez and have assembled on college campuses in Tehran to express their anger and sadness. These protests are motivated by grief, not mere grievance. Grief has opened the way for a new, wider mobilisation.

As my colleague Zep Kalb has observed, looking across recent protests in Iran, “solidarity has been hard to obtain.” Reflecting on last year’s water protests in Esfahan, Kalb explained that the protests forced “ordinary Iranians, state organisations, and political elites” to “compete fiercely about how to share the country’s increasingly scarce water resources.” Communities involved in the protests shared the same grievances—they were all demanding their water rights—but in an environment of scarcity their demands pitted them against one another.

The same can be said for the earlier rounds of economic protests in Iran. The individuals who took to the streets all shared economic grievances and wished an end to their unfair treatment in the face of low wages, high prices, and growing inequality, due in large part to the accumulative effect of sanctions. But the protests, while frequently dispersed, did not overcome class and communal divisions.

The fragmented nature of these past protests has made it easier for authorities to respond with carrots and sticks, shirking calls for broader reform. Last year, Iranian authorities used live rounds to suppress protests in Khuzestan, a region in southwest Iran beset by poverty pollution, and water shortages. Their use of violence in a region many Iranians see as a backwater had limited political repercussions. Earlier this month, the Raisi administration inaugurated a major water infrastructure project to increase water supply in 26 cities in the province. In this way, national resources have been used to address local grievances, while systemic reforms are rejected. After all, many Iranian protestors did not necessarily care if the restoration of their rights and economic welfare came at the expense of others and without broader reform. In this way, the politics of scarcity has undermined the solidarity necessary for broader mobilisation.

But the emotion that has brought so many Iranians to the streets after Amini’s death—grief—is anything but scarce. A photograph of Amini’s parents, utterly alone and in a mournful embrace in the hospital ward, struck a chord and was widely shared on social media. Millions of Iranians have endured such private moments of grief in recent years. The scene in the hospital ward even evoked the unprocessed pain of the COVID-19 pandemic—during which 144,000 Iranians lost their lives according to official statistics. The sadness of Amini’s killing was profoundly relatable.

There is also anger. Another daughter of Iran has had her life ruined or ended by state brutality. Over the last year, apprehensions had grown about the increasingly aggressive actions of the Guidance Patrol and Amini’s killing was the inevitable conclusion.

If Amini’s death seemed inevitable, it was also because the same thing has happened before. Comparisons have been made with the death of the “Blue Girl” in September 2019. Sahar Khodayari set herself on fire as an act of protest and died of her injuries a week later. Khodayari had faced prosecution for attempting to attend a football match at the stadium of Esteghlal, her beloved club, whose uniforms are blue.

Another aspect of Amini’s death, the idea that she was killed simply because she was in the wrong place at the wrong time, has led to comparisons with the January 2020 downing of Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752, in which 176 people were killed. Iranian authorities admitted shooting down the civilian airliner, which was departing from Tehran’s international airport, but claims it was accidental. In the aftermath of such senseless events, many Iranians, especially women and youth, feel they live in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, a nationally representative poll conducted by Gallup in 2021 reveals Iran to be a country beset by anger and sadness. Respondents were asked what emotions they had felt in the previous day. The responses were stark—34 percent experienced anger, 36 percent experienced pain, 40 percent experienced sadness, and 43 percent experienced stress. Responding to Amini’s death, journalist Omid Tousheh captured the national mood succinctly in a tweet: “Grief, anger, and desperation pour forth from the door and the walls.”

The hope for Iran is that these crushing feelings will not lead to dejection. There is a power in the emotions that are being unleashed in this new round of protests. There remains a possibility that a broad mobilisation can lead to reform, if the Iranian people can harness the deep solidarity that grief—not grievance—can foster.

Photo: AP

Is Iran's 'Bread' Subsidy Reform a Half-Baked Idea?

A new round of protests has begun in Iran. People are taking to the streets following a controversial subsidy cut perceived as an increase in the price of bread.

A new round of protests has begun in Iran. People are taking to the streets following a controversial subsidy cut perceived as an increase in the price of bread. These protests were inevitable in a country in which there are so many economic and political grievances and in which civil society and labour groups, demoralised about their ability to influence policymaking through the ballot box, have turned to mobilisations to get their voices heard and their anger registered.

The policy that has triggered the protests has been widely reported as a cut to a “bread subsidy” that has suddenly increased the cost of bread and cereal-based products. This is inaccurate. The subsidy that has been eliminated was an exchange rate subsidy. The government had been providing Iranian importers allocations of hard currency below market prices. This policy indirectly subsidised the purchase of wheat and a few other foodstuffs by the importers. It did not directly subsidise the purchase of bread by ordinary people.

Importers could apply for foreign exchange allocations from the Central Bank of Iran to import wheat. In theory, this would allow them to bring wheat to the Iranian market at a lower price. But in practice, the subsidy had long ago stopped working. Several distortionary effects of the policy were likely generating inflationary pressure across the economy.

First, the exchange rate subsidy was poorly targeted. To put it simply, the Iranian government was intervening to make foreign money cheaper, not bread prices themselves. The subsidy was therefore ill-suited to stabilise prices when Iran’s import needs rose, a periodic occurrence when the domestic harvest falls short of targets. It was also unable to counteract the effects of global increases in the price of wheat. Breads and cereals prices have risen steadily in Iran for years, quadrupling since 2018.

Second, providing foreign exchange at a subsidised rate was exacerbating Iran’s fiscal deficit. Financing this deficit is a major driver of inflation in Iran. The official subsidised exchange rate diverged from the exchange rate on which Iran’s government budget is balanced in 2015. Since then, the spread between the two rates has increased dramatically. The subsidised exchange rate has been fixed at IRR 42,000 since 2019. The exchange rate in the Iranian government budget for the year beginning March 2022 is IRR 230,000. As this spread widened, the Central Bank of Iran faced increasing difficulty in meeting demand among importers for subsidised foreign exchange, creating a foreign exchange liquidity crunch that made it harder to stabilise Iran’s currency outright. In recent years, the Iranian government was spending around $12 billion in hard currency on a subsidised basis.

Third, this additional exchange rate volatility has increased the pass-through effects related to Iran’s dependence on imports more broadly. The Central Bank of Iran has had partial success in stabilising the exchange rate by introducing a centralised foreign exchange market for importers and exporters called NIMA. But Iran’s economic policymakers were tying their own hands in the stabilisation of this exchange rate, which is far more critical for Iran’s economic performance, by diverting precious foreign exchange resources towards essential goods importers. When it comes to inflation generally, the government ought to focus on intermediate goods on which “made in Iran” products depend. The exchange rate subsidy for essential goods was making it harder to stabilise the exchange rate for all other goods.

Fourth, the exchange rate subsidy was always subject to abuse. Particularly in the early years, importers were known to seek and receive allocations of subsidised foreign exchange and either pocket those allocations or turn around and sell on the hard currency to other firms at the market rate. This kind of profiteering was difficult to police. As more scrutiny came upon the allocations, importers with political connections were most likely to continue receiving allocations from the Central Bank of Iran, making enforcement politically fraught.

The evidence that the exchange rate subsidy had failed can be seen in consumer price index data. Bread and cereals inflation has outpaced general inflation since last summer. This is a likely reflection that, in practice, a diminishing volume of wheat imports were being conducted using the subsidised exchange rate—the reform was already being priced-in by the newly elected Raisi government. The sudden price increases were are seeing now are more likely the result of price gouging. Firms across the food supply chain are using the policy reform as an opportunity to raise prices, knowing the blame will be cast on the government.

Whether or not the reform is half-baked, the idea has been cooking in the oven for a long time. The subsidy cut was years in the making and the preferential exchange rate was nearly nixed in 2019, as the Iranian economy underwent a painful adjustment following the reimposition of U.S. secondary sanctions. At the time, the Iran Chamber of Commerce, the voice of the country’s private sector, issued a strong statement calling for the elimination of the subsidy. But the reform was eventually shelved—the Rouhani administration had been cowered by the 2017 and 2018 economic protests, which were instrumentalised by their political rivals.

In the end, the Central Bank of Iran took a different tack. They kept the exchange rate in place but began to eliminate the range of imports eligible for the rate. Initially, importers could apply for subsidised foreign exchange allocations for the purchase of 25 essential goods and commodities. As of September 2021, that list was cut down to just seven goods—wheat, corn, barley, oilseeds, edible oil, soybeans and certain medical goods.

These were preparatory steps for the elimination of the subsidy. In practice, many Iranian grain importers had stopped using the subsidised exchange rate, both in anticipation of its elimination and because it was impractical. One of the fundamental problems facing Iran’s food supply chain is that even when Iranian importers can identify buyers and arrange logistics—difficult things to do when under sanctions—the payments that need to be made for those purchases are often delayed. Importers that were applying to the Central Bank of Iran for allocations of subsidised foreign exchange might wait weeks before the money hit their accounts. Cargo ships would sit idle off Iran’s shores, unable to deliver the grain until the seller received their funds. These delays added costs. The Iranian importers were on the hook for huge fees as the ships they chartered remained out of service. Importers that opted to use the NIMA rate have been able to make payments to their suppliers more quickly and reliably. This is because there is far more liquidity in the NIMA market, in which foreign exchange is supplied by Iranian exporters who are repatriating their export revenues as required by law.

Overall, there is a sound economic argument for eliminating the subsidised exchange rate. But that does not mean that there will not be pain for ordinary people in the short term and the protests are motivated in part by an expectation of further pain. The abject failure to communicate a plan around the subsidy reform will lead to its own distortionary effects, including predatory pricing. Failing to communicate directly and clearly with the Iranian public about this major reform is its own kind of contempt, even if the reform itself is not contemptuous.

In that vein, the elimination of the subsidised exchange rate has been criticised as “neoliberal” and in many respects, it is. As part of the continuity in economic policy, the Raisi administration appears to be continuing the Rouhani administration’s commitment to austerity, seeking relief from inflation through fiscal tightening. The national protests in 2017 and 2018 were triggered by the same anxieties around the government’s perceived failure to protect economic welfare within the Islamic Republic’s social contract.

But on the other hand, this is not a simple economic reform. Iranian officials have likened it to “economic surgery” necessary to repair an economy weakened by sanctions. The reform also does not preclude other redistributive policies. The subsidised exchange rate was a poorly designed and inefficient policy that did more for a small number of elites than it did for Iran’s poor.

The Raisi administration has promised to soften the blow of the reform by providing targeted cash transfers (for two months) to the most vulnerable in Iranian society. Electronic coupons are also being provided. Iran has a good track record with cash transfers, which do something the exchange rate subsidy did not. Such transfers directly boost the consumption of ordinary people in the face of rising prices. If the government can use the fiscal savings from the elimination of an inefficient and poorly targeted policy to shore the economic welfare of Iran’s poor more directly, while also addressing long-running distortions in the foreign exchange markets, this reform may succeed yet. But if the government fails to communicate clearly about its implementation of the reform, the Iranian public will continue to only see failure.

Photo: IRNA

Eyeing Oil Revenues, Iran’s Public Sector Workers Demand Higher Wages

Iran’s public sector workers often mobilise during annual budget negotiations, a drawn-out process involving multiple state actors and institutions.

In its first 200 days in office, the Raisi administration has encountered massive labour mobilisations. In late January, medical personnel across the country’s hospitals and universities joined the picket line. In February, teachers reportedly staged demonstrations in over a hundred urban areas. Last month, pensioners and welfare beneficiaries rallied in more than a dozen major cities.

Motivated mostly by wage grievances, protestors have adopted a range of assertive slogans and demands. In one provincial city, teachers hung up a big banner that read: “Raisi, Qalibaf, this is the final message: the teachers’ movement is ready to revolt.” Pensioners called Raisi a “liar,” blamed his government for neglecting “the nation,” demanded an end to “oppression,” and called for the immediate release of political prisoners.

Commentators have lumped these labor protests together with other recent protest actions. A recent Financial Times report suggested that workers’ rallies and protests over water rights indicate growing popular discontent with the country’s economic record, leaders, and political institutions.

But these broad explanations fail to capture the undercurrents of the labour mobilisations of recent months. Iran’s economy has been doing poorly for years and dissatisfaction with the government is nothing new. It would also be wrong to assume that labour protests are motivated by general public dissatisfaction. In fact, most of the large and coordinated protests have been staged by a rather specific type of worker: state employees. These are relatively educated and privileged workers, employed in protected administrative and professional jobs in Iran’s state bureaucracy and civil service.

Protests by state employees need to be understood in the context of negotiations over the country’s annual budget. The annual budget, which sets wage levels across the public sector, is approved by the Iranian new year in late March. Workers often mobilise during annual budget negotiations, a drawn-out process involving multiple state actors and institutions. Sectoral and labour pressure tends to intensify when negotiations reach their final stages.

While budget-related protests are a routine occurrence, they have been especially widespread this year because workers are emboldened by the prospect of higher oil revenues. The international price of oil has spiked over the past months and state authorities have already revised projected oil revenues upward. Iran is also in advanced negotiations on the country’s nuclear programme, which may result in sanction relief, potentially unlocking billions of dollars in government income.

As employees of the Iranian state, public sector workers hope to benefit from these injections of oil money into Iran’s fiscal system. State employees are mobilising now in an attempt to lock in favourable spending commitments for the upcoming fiscal year. In 2014-2015, when Iran was in similarly advanced talks with the Obama administration over sanctions’ relief, public sector workers also mobilised in large numbers.

A final factor is the legitimacy of the Raisi government itself. Coming to power last year through manipulated elections and record low turn-out, Ebrahim Raisi has been eager to display himself as tolerant and understanding of the country’s impoverished urban middle classes. Raisi has tried to court Iran’s historically reformist-leaning middle classes to gain a degree of popular legitimacy and consolidate his tenuous leadership among various hardliner factions.

Teachers, pensioners, and nurses represent a bloc of reformist-leaning state employees that have coordinated protest actions over the past months. Rather than cracking down on their rallies, security forces have relied on containment and targeted repression—strategies which, so far, have not been successful in preventing further protests.

Teachers have staged by far the largest rallies, winning major concessions in the process. They began protesting right when Raisi came to power in August 2021. Nationwide strikes in November 2021 put pressure on parliament to finalise an expensive piece of employment law that teachers’ unions had long lobbied for. Emboldened by this legislative victory, teachers have continued to protest to make sure that the government allocates enough money to the program.

Teachers, pensioners, and nurses have long complained that government spending prioritises state employees in the armed forces, judiciary, police, and the security apparatus. Over the past months, the government has tried to address their concerns about pay discrimination by reigning in salary increases in these relatively privileged and conservative-leaning parts of the state.

Notably, in January, parliament rejected a bill on payroll spending in the judiciary. Judiciary workers and lawyers immediately responded by taking to the streets, angered by the fact that Raisi, their former boss and patron, had hit their interests so openly. The judiciary protestors argued that they too have a range of legitimate concerns, including having to rely on corruption and bribe-taking to top off their salaries.

In response, the head of the Administrative and Recruitment Organisation justified limiting spending on judiciary salaries by stating that it would “create dissatisfactions in other government bodies.” Mehdi Taghiani, a hardliner MP from Esfahan, made a similar claim. “Severe inflation over the past years has reduced the purchasing power of all workers, not just one specific group in the civil service. If we increase salaries in the judiciary, it will lead to a domino effect by which pay discrimination will eventually lead to the collapse of the government’s financial system,” he stated.

The Raisi government has tried to sell its fiscal policies as prudent and responsible to the outside world. Iran’s finance minister recently proclaimed that the country’s new budget “includes a number of structural reforms.” Such structural reforms, he explains, include “increasing the salaries of government employees at rates less than the inflation rate.”

Yet, the final budget, which was approved several days ago, shows little evidence that the government is committed to austerity and lowering labour costs across the board. The budget increases spending on education by 40 percent, almost double last year’s raise. The government also decided to increase the official minimum wage in the upcoming Persian year by over 50 percent, which will take its real value back to 2017 levels.

In a move away from austerity, the budget contains a variety of cuts and concessions that are part of Raisi’s strategy to mediate between various public sector demands while trying to win over sceptics and opponents. These policies will not only fail to address fundamental labour concerns, but internal rivalries and sectoral interests within the public sector will almost certainly continue to undermine labour solidarity. Teachers and judiciary personnel, for instance, have refused to express support for each other’s struggles. After the judiciary protests in early January, the Twitter feed of Mohammad Habibi, an outspoken leader of the largest teacher’s union, remained unusually quiet. Long-standing competition over the allocation of state resources have led to mutual suspicions will prove difficult to overcome.

Photo: IRNA

Iran’s Water Protests are Not About Water

Esfahan is accused of being privileged as water protests expose regional inequalities in access to the Iranian government.

On November 8, a group of local farmers arrived in the city of Esfahan to protest in front of the offices of the official state news agency and the regional water authorities. The protestors called on the government to release water into the Zayendeh River, which has laid dusty and bare for months, a reoccurring phenomenon. Over the next days, the farmers continued their demonstration in the dried-out beds of the river, camping out close to one of downtown Esfahan’s iconic bridges.

But what started out as a small-scale protest action by farmers from east Esfahan quickly turned into the Ebrahim Raisi administration’s largest popular challenge since taking office in August. On November 19, a day after negotiations between the Esfahan Farmers’ Union and the regional government broke down again, thousands of city-dwellers suddenly joined the farmers to demand that the Zayandeh River be filled up.

The government’s initial response to the mass demonstration was conciliatory and supportive. State media broadcasted the Friday rally widely. Officials came to speak to the protestors directly, expressing their sympathy and promising to address the problem promptly. The minister of energy even formally apologised to the farmers, saying he felt “ashamed” that the government had failed to provide enough water.

Soon enough, the tone changed. Within days, security forces moved in, cracking down on the remaining protestors. Police brutally dispersed the protestors and destroyed their tents. On social media, images of farmers drenched in blood circulated widely.

In theory, water protests should have broad popular support in Iran. Not only is the country mostly arid and semi-arid, but Iranians have also suffered from worsening draughts and environmental degradation provoked by climate change, government mismanagement, and economic sanctions.

In reality, however, solidarity has been hard to obtain as ordinary Iranians, state organisations, and political elites compete fiercely about how to share the country’s increasingly scarce water resources.

Many of these rivalries are long-standing, and they broke out again following the Esfahan protests. In the capital of the neighbouring Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari province, hundreds of residents and farmers took to the street to protest against the Esfahan protestors’ demand for more water. The Chaharmahal protestors argued that their province, located in the mountainous Zagros region of southwestern Iran, already supplies too much water to the dry central plateau region, of which Esfahan is part. In turn, Esfahan farmers deployed an old tactic: they sabotaged the water pipes headed to the even drier Yazd province, arguing that “their” water is unjustly being diverted elsewhere.

This nasty and zero-sum type of group politics has become deeply entrenched in Iran over the past two decades. In this configuration, Esfahan province has certainly emerged a winner. Its rural residents earn on average about a quarter more than peers in the Zagros region or Khuzestan, which is home to the Karoon, the largest river in Iran. Moreover, Esfahan’s urban and provincial elites have been successful in turning local distributional conflicts over water use into demands for more water from the Zagros. Farmers from eastern Esfahan have long complained about excessive water use by the city of Esfahan. Regional authorities have used these protests to claim more water from upstream provinces.

Yet, rather than being diverted to eastern Esfahan, much of that extra water has gone into urban consumption and toward large-scale steel manufacturers in the region. These inefficient and wasteful factories, mostly built before the 1979 revolution, are heavily subsidized by a central government keen to maintain a degree of self-sufficiency in steel production.

It is perhaps unsurprising that, following the November 19 demonstrations, much of the debate on social media centred on Esfahan’s privileges. One popular Twitter user argued that “Esfahani greed is what has turned the Zayendeh River into an issue. Esfahanis do not only want [to produce] steel but they also expect the water of Khuzestan and Chaharmahal to be transferred to this industry. If we are to believe you, you should protest in front of the Mobarakeh and the Esfahan Steel Companies.”

Rather than blaming specific individuals, entities, or social groups, many other activists accused the “water mafia” for the opaque and mean-spirited machinations of the country’s water politics. Seyyed Yousef Moradi, an environmental activist from Yasuj, commented that: “Even though you think that people from the Zagros Mountains are simple, we are not ignorant. We understand that a ten day sit-in in Esfahan for water provision, with the wide-spread support of media and the government, is a part of the water mafia’s plan to justify projects to transport water from the deprived provinces of the Zagros.”

The term “water mafia” is also popular among the country’s political elites, who are keen to avoid direct confrontation among each other, and fear turning the conflict into an ethnic struggle between the Persian majorities of the central plateau and the Arab, Lor, and Bakhtiari minorities of southwestern Iran.

Indeed, while Esfahan’s relative wealth and power is undeniable, upstream provinces and groups do not lack political representation. In the past, the local elites in the Zagros and Khuzestan have often supported their constituents’ protests about water rights. For instance, in early 2014, the local MP and the local representative of the Supreme Leader came to the support of several thousand people who had gathered in Shahr-e Kord, the capital of Chaharmahal province. The protestors demanded a halt to construction work on tunnels designed to transport water to the central plateau.

Following similar protests in Khuzestan in the summer of 2016, Ayatollah Abbas Ka’bi, the province’s representative in the powerful Assembly of Experts, issued a fatwa prohibiting the transfer of water from Khuzestan to the central plateau for agricultural or industrial purposes. When rumours circulated last July that these water tunnels had been officially opened—thus breaking the religious ruling—protests flared up across the province. Initially, Ayatollah Ka’bi supported the protestors and called the demonstrations legitimate. He turned quiet when, as protests continued and spread over the next days, security forces decided to crack down violently.

The July protests in Khuzestan and the November protests in Esfahan are intimately related. The Esfahan protests, and the Esfahan Farmers’ Union’s failure to reach an agreement with the government over the Zayendeh River’s fate, is at least partially the product of recent struggles in Khuzestan and the Zagros to prevent the transfer of water to Esfahan. Because water in Iran is not a public good, the protests are not really about water. Rather, what protestors are fighting for is access to the government. Protestors want the government to enable their consumption of water.

For their part, state authorities are locked in a delicate balancing act. Strapped of cash in the face of a severe US-led sanctions regime, the government has not been able to cough up the investments necessary to update the country’s outdated irrigation systems and water infrastructures. While security forces are eager to crack down on what they perceive as disturbances and unrest, many other state elites are caught between, and often on the side of, various social groups and their competing demands for water.

In order to make water resource management in Iran more efficient, fair, and equitable, the country needs to move beyond its current form of interest group politics. Unfortunately, there are few indications that the broad-based solidarity such a movement requires is in the making. As a result, it is likely that water protests will continue to flow.

Photo: IRNA

Iran’s Emboldened Workers Press New President for More Concessions

A wide range of social groups in Iran have been mobilising to express their socioeconomic grievances. Grappling with concessions made by the previous administration, Iran’s new president is on the back foot.

In the third week of September, teachers in dozens of towns and cities across Iran took to the streets, calling on the new president, Ebrahim Raisi, to fully implement existing labour laws. The authorities responded quickly and positively, promising to work on an implementation plan. But the teachers are not ready to back down. In an interview conducted for this article, a leader of the main teachers’ union said his organization will continue to use a “carrot and stick” approach to ensure that the Raisi administration makes good on its promises.

The latest nationwide demonstrations by teachers are part of a bigger protest wave that has gripped Iran over the past year. In the first few months of the year, pensioners mobilised in Tehran and other major cities. In July, residents of the southern province of Khuzestan protested water shortages. Between June and August, contract workers across Iran’s oil sector staged intermittent strikes and demonstrations. These protests are unlikely to let up. A wide range of social groups have been mobilising—organising locally, regionally, and nationally—to express socioeconomic grievances.

As these protests have continued, the Raisi administration has defied predictions that it would quickly impose order on Iran’s restless society. Raisi was elected president in June after extensive electoral manipulation and a record low turnout. But that Iran’s new leadership came to power with little regard for the electorate has not dissuaded protestors from making demands of state authorities. According to one protest tracker, September—Raisi’s first full month in office—saw one of the highest number of protest events in the past year.

Raisi has been forced to grapple with the promises made by his predecessor, Hassan Rouhani. Rouhani launched his first term with a vow to bring inflation under control and spend government resources prudently. He exited office last August having promised financial support to a wide range of groups and sectors. Rouhani’s commitment to inflation reduction was sincere and, initially, successful. After carefully and painstakingly negotiating sanctions relief and rebalancing the economy between 2013 and 2017, his successes were quickly undone by the twin shocks of the Trump administration’s reimposition of sanctions in May 2018 and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in February 2020. Realising that fiscal prudence would not be enough to shore the Iranian economy, Rouhani decided to direct spending towards his core constituents, namely the urban middle classes.

As Djavad Salehi-Isfahani has shown, Tehran and urban areas were largely spared the rapidly rising poverty rates seen in Iran’s rural communities after 2018. To prevent further slides in the incomes of pensioners and public sector teachers—two important middle class segments generally aligned with reformist politics—the Rouhani administration consistently increased the budget share allocated to education and social security. As Kevan Harris observes in a recent report, education and social security together accounted for over 55 percent of the 2021-2022 budget, up from less than 45 percent just four years earlier. The more the Rouhani administration intervened to support the welfare of key constituencies, the more groups such as teachers and pensioners became emboldened, increasing their demands as the deteriorating economic situation eroded their incomes. Protest activity grew despite the growing risk of state repression.

Still, Rouhani’s constituents suffered despite his targeted interventions. Public sector teachers saw their real wages fall by over 40 percent between March 2018 and March 2021. Middle class workers employed in the public sector suffered significantly as government spending ran out of steam. Private sector wage workers, such as those in the construction sector, have fared comparatively better as their wages rise with inflation.

Faced with discontented workers and limited fiscal space, the Raisi administration has sought to blame their predicament on Rouhani’s recklessness, rather than the deteriorating economic situation. Hardline politicians argue that Rouhani deliberately loaded up on financial commitments in his final days in office in order to put a stick in the spokes of the Raisi government. Parliament member Ahmad Hossein Falahi recently complained that “unfortunately in the final days of the Rouhani administration a lot of things got done. This is because the managers of the previous government aimed to impose a number of policies on the incoming administration, despite the fact that the Plan and Budget Organization was supposed to safeguard this year’s budget.” Falahi added that this has created a dangerous “mentality” whereby social groups invoke Rouhani’s generosity to bargain with the Raisi government.