What You Should Know About Iran's Weakening Currency

The rollercoaster ride that has taken the rial to a historic low of IRR 215,000 to the dollar does not tell us as much about the health of the Iranian economy as is widely assumed.

The Iranian rial has hit a historic low against the dollar, adding to the perception that the country is in the throes of a deepening economic crisis. But the figures that are most concerning for Iranian economic policymakers (there are many) are rarely the most dramatic or those that make the headlines. The rollercoaster ride that has taken the rial to a historic low of IRR 215,000 to the dollar does not tell us as much about the health of the Iranian economy as is widely assumed.

Reporting on Iran’s currency focuses on the azad or free market rate, which is the price of purchasing a single, physical dollar bill at an exchange bureau in Tehran. The buying and selling of eskenas, or hard currency, represents a small proportion of the overall foreign exchange market in Iran, likely accounting for less than 20 percent of all foreign exchange transactions.

There is also a fixed subsidized rate of IRR 42,000 for each dollar. This rate is made available to importers of critical goods such as food and pharmaceutical products, but the Iranian government has been seeking to shrink the number of goods eligible to be imported at this rate.

The most important rate, which is rarely cited in reporting on Iran’s currency woes, is the rate available in the NIMA exchange, a centralized electronic system established by the Central Bank of Iran in 2018 to streamline the purchase and sale of foreign exchange among Iranian companies. The NIMA rate has hit just over IRR 168,000 in the past week, also a historic low.

The NIMA rate has also risen in recent months, reflecting the reported shortages of foreign exchange available in the market due to trade disruptions brought-on by COVID-19 as well as the underlying difficulties facing Iranian banks, and particularly the Central Bank of Iran, in accessing foreign exchange held in accounts at foreign financial institutions.

After approaching convergence in the summer of 2019, the spread between the free market and NIMA rates has widened considerably, meaning that the devaluation of the rial in the free market is not the best indicator of the strength of the rial, nor an accurate reflection of concerns around inflation.

Since the NIMA exchange began operating in earnest in the last quarter of 2019, inflation, as measured by the consumer price index, has tracked most closely the NIMA rate and not the free market rate. This is to be expected. The NIMA rate reflects the price at which most foreign currency is bought and sold in Iran and crucially it reflects the price at which Iranian companies purchase foreign exchange in order to pay for imported goods.

On one hand, the devaluation of the rial over the last decade has benefited Iranian exporters, making their goods more attractive to foreign buyers. The more liberal approach to foreign exchange policy has helped Iran grow its non-oil exports—a lifeline for the economy as oil exports are constrained by sanctions.

But on the other hand, the more liberal approach to the exchange rate has had an impact on the price of imported goods, whether those are finished goods or raw materials and parts used in the manufacturing of finished goods in Iran. This relationship is most clear when comparing the changes in the NIMA rate with the price index for consumer durables, a category of goods more likely to have imported parts content. When the NIMA rate increases, so does the price of durable goods, contributing to the total cost of the consumer basket.

Often, reports about the plunging value of the rial suggest that the appreciation of the dollar in the free market reflects the erosion of Iranian purchasing power. But the relationship between the rial’s free market rate and inflation is limited. Unlike in other economies that have experienced currency crises, such as Lebanon, Iran’s economy is not dollarized. When ordinary Iranians exchange rials for physical dollars, they are acquiring an asset that they will most likely exchange back into rials at some future point, preserving the value of their savings in the process. Iranians purchase dollars for the same reason they purchase gold, real estate, and even used cars—they are seeking a hedge against inflation. Hard currency dollar appreciation does not depress the value of the rial as a medium of exchange.

However, the free market rate could be a signal for price makers about expectations of future inflation, and therefore may influence producers and retailers to increase prices. Moreover, the free market rate may also have an impact on the price of real estate, which is also used as a hedge against inflation. In both instances, the devaluation of the rial in the free market could contribute to higher prices for Iranian households.

But when considering that the free market represents a small proportion of the overall foreign exchange market in Iran, fluctuations in the free market rate are perhaps best understood as a response to inflation, among other economic indicators. In fact, at a time when the central bank is pumping historic amounts of liquidity into the Iranian economy, the conversion of rials into dollars may actually serve to absorb some liquidity.

This is perhaps the other parallel that can be drawn between the purchase of dollars and assets such as stocks and gold—the currency free market has some of the hallmarks of a bubble, particularly as the spread with the rates available on the NIMA exchange widen. The devaluation of the rial that can be observed in the NIMA exchange, which is equivalent to the rial losing about a third of its value since Iran reported its first two cases of COVID-19 in February, lags behind the devaluation in the free market exchanges, which has seen the rial lose half of its value in the same period.

Given the media attention both inside and outside of Iran to the rial’s free market fluctuations, it is perhaps no surprise that psychological factors may be responsible for the recent devaluation episode. Given that the NIMA rate is a better indicator of the vulnerability of the Iranian economy to inflation, both when considering how much foreign exchange is available in the market, but also when considering changes in the money supply in Iran, it is notable that the free market rate has deteriorated more sharply.

This divergence, which the central bank had worked hard to limit, is beneficial to a wide range of actors within Iran’s financial system, including those engaged in corruption. The arbitrage between the two rates incentivizes commercial enterprises that earn foreign exchange revenue to circumvent the NIMA system. The panic buying of dollars by working class Iranians benefits wealthy Iranians who are more likely to maintain a large portion of their savings in hard currency, or who can bring hard currency back to the country from abroad. Ironically, in the short term, the devaluation of the rial has probably created more wealth than it has destroyed

Nonetheless, Iranians should be worried about inflation. The COVID-19 crisis has widened Iran’s fiscal deficit and also given rise to balance of payments challenges. There is growing concern that inflation will rise in the coming months as the central bank prints money.

Iran’s central bank governor, Abdolnasser Hemmati, has sought to calm nerves by arguing that increased liquidity is a “structural phenomenon” in the Iranian economy. His statements have yet to reduce demand for dollars, which has risen in anticipation of increased inflation. Nonetheless, the increased demand does not itself mean that Iran is presently experiencing or is set to experience the scenarios of “hyperinflation” that have been long predicted. Rather, those purchasing dollars in the free market are betting that the policymakers will fail to keep inflation under control as it edges towards 30 percent.

Photo: IRNA

Governor of Sweden’s Central Bank Visits Iran for Technical Dialogue

◢ The governor of the Riksbank, Sweden’s central bank, is visiting Iran on April 5th on the invitation of Iran’s central bank governor Valiollah Seif. With an agenda focused on technical exchanges, a spokesperson for the Riksbank confirmed to Bourse & Bazaar that Ingves will give a presentation entitled “Central Banking and Financial Crisis: Lessons Learned.”

The governor of the Riksbank, Sweden’s central bank, will visit Iran on April 5-6 at the invitation of Iran’s central bank governor Valiollah Seif.

Stefan Ingves, the governor of the Riksbank will be leading a day of technical exchanges including a working dinner hosted by Sweden’s ambassador in Tehran, Helena Sångeland. The visit, which comes as political uncertainty around the nuclear deal reaches a fever pitch, underscores the long-standing commercial and economic relationship between Sweden and Iran. In February of 2017, Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Löfven visited Iran with an itinerary that included a visit to the Scania truck factory in Qazvin.

For the Central Bank of Iran, the visit by one of Europe’s most seasoned central bankers is a valuable opportunity to draw on the Riksbank’s experience in central banking, financial stability, and monetary policy. Ingves has held the position of Riksbank governor since 2006 and navigated the country through the 2009 global financial crisis. He is also the chairman of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, which sets global standards for prudential regulation of banks. Iranian banks have been undertaking extensive reforms in order to better conform to so-called “Basel” standards.

A spokesperson for the Riksbank confirmed to Bourse & Bazaar that Ingves will give a presentation entitled “Central Banking and Financial Crisis: Lessons Learned.” The topic is of particular relevance as Iran seeks to manage systemic risk in its banking sector stemming from non-performing loans, a key driver of the 2009 crisis. Sweden was one of the fastest recovering countries in the aftermath of the last major global recession, earning praise as a “rockstar of the recovery” for its combination of intelligent fiscal and monetary measures.

No doubt, Iran’s central bankers will listen to Ignves’ presentation attentively.

Photo Credit: Riksbank

To Break With Austerity, Rouhani Must Deliver on Sovereign Debt Sale

◢ To win foreign investment, Iran's needs to boost development expenditures. But expansionary fiscal policy will require a new source of revenue, as oil sales remain stagnant and tax rises remain politically risky.

◢ A sovereign debt sale, long discussed by Iranian officials, is the fundamental way Iran can find the revenues to self-fund growth. The Rouhani administration must focus on making its bond offering a reality.

One of the remarkable, and yet little discussed, aspects of the Iranian election is that Hassan Rouhani triumphed despite being an austerity candidate. His first term was notable for its frugal budgets and commitment to both slash government handouts and reduce expenditures in an effort to tackle inflation. On one hand, the focus on a more disciplined fiscal and monetary policy meant that Rouhani could point to a successful reduction of inflation from over 40% to around 10% while on the campaign trail. On the other hand, job creation has been stagnant and the average Iranian has seen little improvement in their economic well-being.

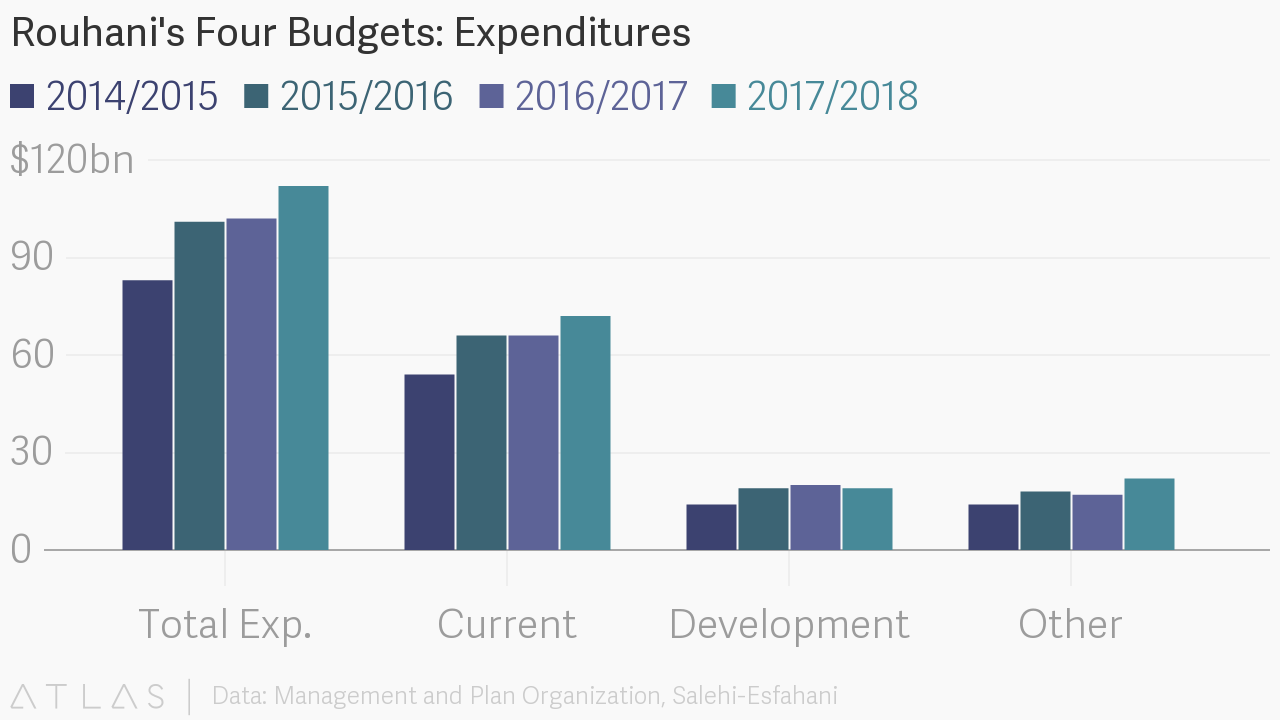

Some economists, including Djavad Salehi-Esfahani, have argued that Rouhani’s austerity economics are misguided, depriving the economy of vital liquidity that could help jumpstart investment and job creation. For example, Iran’s 2017/2018 budget sees tax revenues stay constant at an equivalent of USD 34 billion despite the fact that economic growth is expected to top 6%. Salehi-Esfahani believes that these figures reflect the Rouhani administration's belief “that letting the private sector off easy would encourage it to invest.” The government, meanwhile, will not contribute much more in investment. Development spending is set to decrease from USD 20 billion to USD 19 billion.

Surely, the Rouhani administration’s pursuit of a small government that leaves the burden of job creation and economic growth to the private sector is admirable. It represents a significant shift in the mentality that has characterized the economic policy of the Islamic Republic, which has long relied on state-owned enterprise and state-backed financing, supported by oil revenues, to drive economic growth.

But the volume of investment needed to revitalize economic sectors and create substantial job opportunity has not yet materialized. This is an undeniable fact, which Rouhani has attributed to failures on the part of Western powers to adequately implement sanctions relief, leaving international banks unable to work with Iran. Rouhani’s opponents meanwhile, attributed low volume of foreign direct investment to his administration's mismanagement. There is truth to both accounts.

In many ways, Rouhani’s lean towards austerity was a response to the spendthrift policies of his predecessor, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. The Ahmadinejad administration responded to faltering economic growth during a period of historic oil revenues by ploughing oil rents into the banking system and compelling banks to issue loans. These loans were often provided without the adequate due diligence and were used not to finance growth, but increasingly to fuel speculation, or more forgivably, to address cash flow difficulties faced by companies as a result of international sanctions.

As a result, Iran’s banking sector is now weighed down with a high proportion of non-performing loans, accounting for around 11% of total bank debt. When bank balance sheets grew increasingly precarious as non-payment of loans mounted in the sanctions period, competition for deposits grew. Exacerbating this competition, banks needed to provide higher deposits rates in order to stay ahead of inflation. The combination of forces pushed interest rates up to all-time highs.

The debt market in Iran is now broken. The IMF has urged urgent action to “restructure and recapitalize banks.” In the meantime, banks remain disinclined to lend and in the instances where healthier banks are able to provide loans, borrowers must contend with the high cost of debt.

This may help explain why the Rouhani administration so aggressively sought to address inflation—it was a necessary step to reduce the benchmark interest rate, which has so far been reduced from a high of 22% in 2014 to the current rate of 18%.

But even at such time that interest rates normalize, barriers will remain to the use of debt markets. At a structural level, Iranian companies, particularly in the private sector, rely on equity financing rather than debt financing in order to fund growth. This reflects a “bloc” behavior within Iranian enterprise. Partially as a consequence of the continued dominance of family-owned businesses in Iran’s non-state economy, business leaders tend to approach financiers within their own networks or holding groups, and many of Iran’s largest companies and banks anchor conglomerates that grew out of sequential processes of a kind of inward-looking venture capital. There is limited comfort among Iranian business leaders to seek funding from groups outside of these tight networks and by the same token, equity investors hesitate to provide finance projects outside their own networks. This means that the pool of available investor capital is rarely competing across the whole pool of available capital deployments—a significant inefficiency.

Growth-oriented investing itself can be a difficult strategic proposition. Iranian business leaders have understandably prioritized weathering periods of uncertainty over the execution of long-term plans. The challenge of dealing with short-term volatility has naturally favored short-term thinking. Major companies are only recently undertaking strategic reviews that might identify needs to invest in capital improvements or new services in order to drive growth in support of long-term goals.

The combination of the bloc effect in equity financing and the broken debt market creates a major brake on economic growth, especially from a supply-side perspective. To restore momentum, a third party is needed to order to reset the incentives and mechanisms around financing in Iran.

From the outset of its tenure, the Rouhani administration has hoped foreign investors would take on this role. An influx of foreign investment would have triggered growth without requiring the Rouhani administration to pursue difficult political gambles, such as expanding government expenditure for growth investments in the same period in which welfare programs are being culled. Moreover, the administration’s budgetary leeway was significantly reduced given the persistently low price of oil, making any such balancing act even more fraught.

Eighteen months after Implementation Day, it is clear that the administration significantly overestimated both the attractiveness of the market and underestimated the hesitation of major banks to resume ties with Iran. Investing in Iran is neither easily justified nor easily executed.

The country lacks two essential qualities that have characterized most emerging and frontier markets in the last decade. First, most emerging economies are not as diversified as Iran’s, and do not have such a large arrange of incumbent players with whom any foreign multinational or investor will need to compete for marketshare. There tend to be more “greenfield” opportunities in which lower capital commitment can generate higher returns. Second, a nearly universal feature among emerging markets is the consistent application of both expansionary monetary and fiscal policy. Such policy makes it possible for each investor dollar to achieve a higher return.

In its commitment to reduce interest rates and return the debt markets to normalcy, the Rouhani administration is pursuing an appropriate monetary policy—eventually lenders will become active again. But what remains perplexing is the insistence on austere government budgets in the face of low commitment from foreign investors.

It is clear that the Rouhani administration cannot easily spend tax and oil revenues on long-term projects. Oil revenues are stagnant and there is limited political will to raise taxes. At current levels of government revenue, the political risks of such expenditure are high; as the presidential election showed, populism remains a potent rallying cry among Iranian voters. But foreign investors can’t be expected to step into the gap. Direct equity investments remain a hard sell when domestic financing, whether in equity or debt form, remains throttled and liquidity challenges abound.

There is however a feasible solution that has seen much discussion, but little action—Iran’s return to international debt markets. A sovereign bond issue would both provide Iran’s government the opportunity to raise expenditures in a way that does not draw from existing sources of state revenue by providing a wide class of investors exposure to Iran’s expected period of economic growth. Such a security, ultimately backed by the country’s oil revenues, would serve to mitigate perceptions of country risk for creditors.

In May of 2016, Iran’s finance minister Ali Tayebnia disclosed that discussions were taking place with Moody’s and Fitch over restoring Iran’s sovereign credit rating. One year later, the debt sale continues to be a point of discussion. Recently, Valliolah Seif, Governor of the Central Bank of Iran, commented that the country will issue debt “when [Iran] becomes certain that there is demand for [its] debt.”

Seif’s comments allude to the essential problem of Iran’s planned debt sale—marketing. In order to get Iranian bonds onto the market in any substantial way, the country would need the support of major international banks to serve as underwriters. But banks remain hesitant due to sanctions and political risks.

Turkey, a country which presents creditors significant political risk without mitigation of oil revenues, was able to raise USD $2 billion in a Eurobond sale in January of this year. The sale was underwritten by Barclays, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs and Qatar National Bank.

Iran, is fundamentally a more attractive investment opportunity than Turkey. But major banks remain hesitant to provide financial services to Iran. The Rouhani administration needs to make the sovereign debt sale a core focus of its dialogue with European and global counterparts, and insist on political and technical support in order to entice 2-3 major banks to come on board. In the same manner that the Joint-Commission oversees implementation of the Iran nuclear deal, a multidisciplinary working group needs to be formed to manage the implementation of the debt sale. With the right stakeholders engaged, one can a combination of early-mover banks from Europe, Russia, and Japan agreeing to underwrite the bond issue.

Encouragingly, the delays may have played to Iran’s favor. Emerging markets are just now beginning to rebound, and investors have driven sovereign debt sales to record highs. The Rouhani administration must seize this opportunity and move beyond the limitations of its present austerity economics.

Photo Credit: Wikicommons

Let It Rule: Imperatives for Central Bank of Iran

◢ In most countries, central bankers wield immense influence over the economy through their monetary policy.

◢ The Central Bank of Iran has struggled to secure the power and independence of its foreign equivalents, hindering economic planning and growth.

“And God said, Let there be light: and there was light.” A central bank’s power is somewhat like God’s, at least in monetary terms, as a former governor of the Central Bank of Iran once said. This is true for the world's most influential central banks such the Fed, ECB, BOJ and BOE or the SNB. The Swiss National Bank's recent move to abandon a self-imposed peg of the Swiss franc against the euro, introduced in 2011, sent the Franc soaring against the Euro by almost 40 percent, is a testament to the power they exert.

But, the CBI is far from wielding the power and independence that its foreign counterparts enjoy.

The bank is under strict financial sanctions, which have diminished its foreign reserves. Thus it has lost face in the foreign exchange market. Gone are the days when remarks by its governor calmed traders. In recent years, even its actions have little effect. In 2012, the bank had to resort to closing down all currency trade in a bid to halt the collapse of the rial, when vows to stabilize exchange rates and financial intervention failed. At that point the bank had overplayed its hand so much so that traders saw the bank reactionary and imprudent. Little has changed in this regard.

Defenders of the bank might counter that the siege on the CBI for allegedly circumventing sanctions against Iran's nuclear energy program is the source of its ineptitude. And yes, having $100 billion trapped overseas does hurt a lot. But that's not all.

Just look at the list of issues the bank is contending with and you'll see that even with a $100 billion, the leopard doesn't change its spots!

It is struggling to bring 7,000 rogue financial institutions, including one Ayandeh bank, under its supervision. The CBI has tried and failed to decrease interest rates for the past year. But, the same institutions have not complied, leading to drainage of deposits from banks towards their coffers.

Furthermore, past monetary decisions by the central bank and the former government have led to tens of billions of dollars of toxic debt on the balance sheets of state-owned commercial lenders, in turn driving them towards property speculation. The central bank is seeking to undo this knot in a civilized way, without undue panic and bankruptcies. Results will materialize slowly, if at all.

When we consider the inability to craft effective policy, at the heart of the matter are the limitations on the central bank's legal powers and its authority to make key decisions.

In most developed countries, monetary policy is the domain of a central bank’s governors. Not so in Iran. The money and credit council, a body within the central bank but controlled by the government, sets monetary policy, not the governor and his deputies. This essentially makes the bank an arm of the Ministry of Finance.

The bank also plays the role of the treasury for the government. It receives oil revenues, and then prints rials and distributes the funds to various government branches. Sometimes the foreign receipt part doesn't take place, thus curbing the bank's control over inflation.

And even when the policies are made, the bank is too feeble to implement them. It doesn't have the capability to exert pressure on banks or the currency market, let alone combat those who defy its commands.

So how can investors and business leaders ask for inflation to be restrained, monetary policy to be set and the currency's value to be stabilized, if they are to rely on such a central bank?

Luckily, the solution is simple enough, at least on paper. A separation of powers is necessary. Monetary policy should be detached from fiscal policy, and the bank should be isolated from politics.

To do so, the bank should be given full autonomy on monetary matters, a structure similar to that enjoyed by its counterparts in developed nations. A system of governance, where by all three branches of government have a degree of influence in the bank's governance would better guarantee the bank's autonomy. But this would require a change in the constitution, a lengthy and difficult process.

Furthermore, the central bank's legal clout and ability to exert power on its turf needs augmentation. Its influence has to cut through the lobbying of vested interests. Its responses to crime must become rapid. For this it needs more legal powers and a wider array of financial tools to help it set and oversee monetary policy. Again lawmakers must empower the bank for the benefit of investor, business leaders, and the economy at large.

Many officials in the current administration have expressed their desire to give CBI greater autonomy and new legislation is under work to give the bank some new powers. But a half-hearted will not be effective. What is needed is a fully independent central bank, as enshrined in law and in the deference of the financial sector at large. After all a strong and independent central bank will help iron-out the full range of economic policies. We ought to let the governor rule his domain.

Photo Credit: mebanknotes.com