Participatory Budgeting Opens Path for Democratic Reform in Uzbekistan

A participatory budgeting initiative may prove a vital step forward in Uzbekistan’s political development if it opens the path to wider democratic reforms.

Since his inauguration in 2016, President Shavkat Mirziyoyev has paved the way for many policy reforms in Uzbekistan. Four of these reforms stand out as truly consequential.

The first two reforms are economic. The move to a mostly market-based foreign currency regime and the implementation of tax reforms delivered significant positive stimuli for economic growth and helped to open the Uzbek economy to foreign investment.

The third reform put an end to the abhorrent practice of state-sponsored forced and child labor. Possibly more than any other, this reform has earned Uzbekistan international praise. The Economist named Uzbekistan “country of the year” in 2019, describing it as a country “that abolished slavery.” Although labour rights and state intervention issues persist in cotton production clusters, the reform effort still successfully stigmatised forced labor among top officials, improved many labour conditions, and opened the Uzbek cotton and textile industry to international trade.

The fourth reform has garnered less international attention but is no less significant. The Citizens’ Initiative Budget is a participatory budgeting platform that lets the public decide where they think it is best to spend public money. The policy aims at better redistribution through decentralization of budget planning.

The initial outcomes are exciting: 7.8 million votes were cast in support of 61,500 spending projects in 2022. The votes determined the allocation of USD 100 million across 98 percent of all micro-districts (mahallas) in Uzbekistan. Compare this to 2021, when 6.72 million votes were collected on 69,700 projects. This year voter turnout increased, while the collective action improved with fewer—and likely more realistic—nominated projects. It is estimated that 33 percent of Uzbek adults participated in the voting process in 2022. A prominent blogger suggested that the participatory budgeting process was the country’s most competitive election. While tongue in cheek, this reaction to participatory budgeting points to its significance—people mobilise and vote for the option that best represents their needs.

Without true electoral accountability in the country, Uzbekistan’s central government often receives distorted signals from its people. That is why reforms that leverage the tools of participatory democracy are so crucial. Arguably the most significant recent example of distorted signals was when in July of this year Karakalpakstan’s legislature and government unanimously supported the constitutional amendments to dissolve its semi-autonomous status. Mass civil unrest erupted leading to deaths, injuries, and property damage. President Mirziyoyev later berated the Karakalpak lawmakers for failing to communicate the people’s concerns and wishes to the central government.

Alongside the participatory budget, another valuable source of signals is Uzbekistan’s media environment, which has become more free since 2016 as outspoken bloggers and probing journalists write for a range of independent digital media outlets. Even though the state-owned national television, radio, and print media have little impact on policymaking and there remains censorship, the Presidential Administration now regularly cites Telegram messages and local reports when demoting bureaucrats and municipality heads—a sign that the media is supporting accountability. Investigative reporting also sometimes forces municipal or regional authorities to abandon or adjust unpopular decisions before public anger escalates.

As promising such anecdotal occurrences of accountability may be, they do not and cannot accurately represent or equitably empower all the people of Uzbekistan. For one, there is a clear digital divide in how many people own smartphones and can afford or access the internet. Richer urban areas with better education, more infrastructure, higher incomes, and more active civil society enjoy a greater capacity to mobilise and take advantage of initiatives like participatory budgeting. These divides can be self-reinforcing. Therefore, as a rule, central governments try to keep urban residents more content.

Another reality is that such feedback channels mostly enable short term policy interventions, and do not necessarily help in gauging long term sustainable development priorities and population needs. While participatory approaches and media attention can help citizens respond when, for example, a green space is endangered, other important decisions about where to build roads and schools or when hire doctors and buy vaccines have much steeper collective action costs. Without regular bottom-up elections, in which politicians are asked to define their policy agendas and are held accountable to those agendas, it is difficult to collect informational signals on what the population wants even if everyone agrees on the essentials.

The Citizens’ Initiative Budget may prove a vital step forward in Uzbekistan’s political development if it opens the path to wider democratic reforms. Such reforms may be necessary if Uzbekistan wants to build on five years of strong economic growth—social scientists agree that the quality of political institutions determines economic outcomes.

Encouragingly, Uzbekistan is set to substantially expand its participatory budgeting platform. In 2022, the government will increase funding to nearly USD 250 million and has pledged at least USD 700 million to be disbursed in 2023. Moreover, the government has proposed that all infrastructure projects in micro-districts will be funded through participatory budgeting. A recently circulated draft white paper from the Presidential Administration suggests granting 28 districts expanded local governance authority, giving local legislators full-time paid employment, and empowering local residents with the ability to recall underperforming lawmakers and officials.

Ultimately, the essential condition for good governance at any level is enabling free and fair elections. Free and fair elections will optimise distribution of economic resources, enable growth, reduce corruption, and advance inclusion and happiness. As the success of the Citizens’ Initiative Budget shows, the Uzbek people are ready to take charge of their shared political future.

Photo: AXP Photography

To Break With Austerity, Rouhani Must Deliver on Sovereign Debt Sale

◢ To win foreign investment, Iran's needs to boost development expenditures. But expansionary fiscal policy will require a new source of revenue, as oil sales remain stagnant and tax rises remain politically risky.

◢ A sovereign debt sale, long discussed by Iranian officials, is the fundamental way Iran can find the revenues to self-fund growth. The Rouhani administration must focus on making its bond offering a reality.

One of the remarkable, and yet little discussed, aspects of the Iranian election is that Hassan Rouhani triumphed despite being an austerity candidate. His first term was notable for its frugal budgets and commitment to both slash government handouts and reduce expenditures in an effort to tackle inflation. On one hand, the focus on a more disciplined fiscal and monetary policy meant that Rouhani could point to a successful reduction of inflation from over 40% to around 10% while on the campaign trail. On the other hand, job creation has been stagnant and the average Iranian has seen little improvement in their economic well-being.

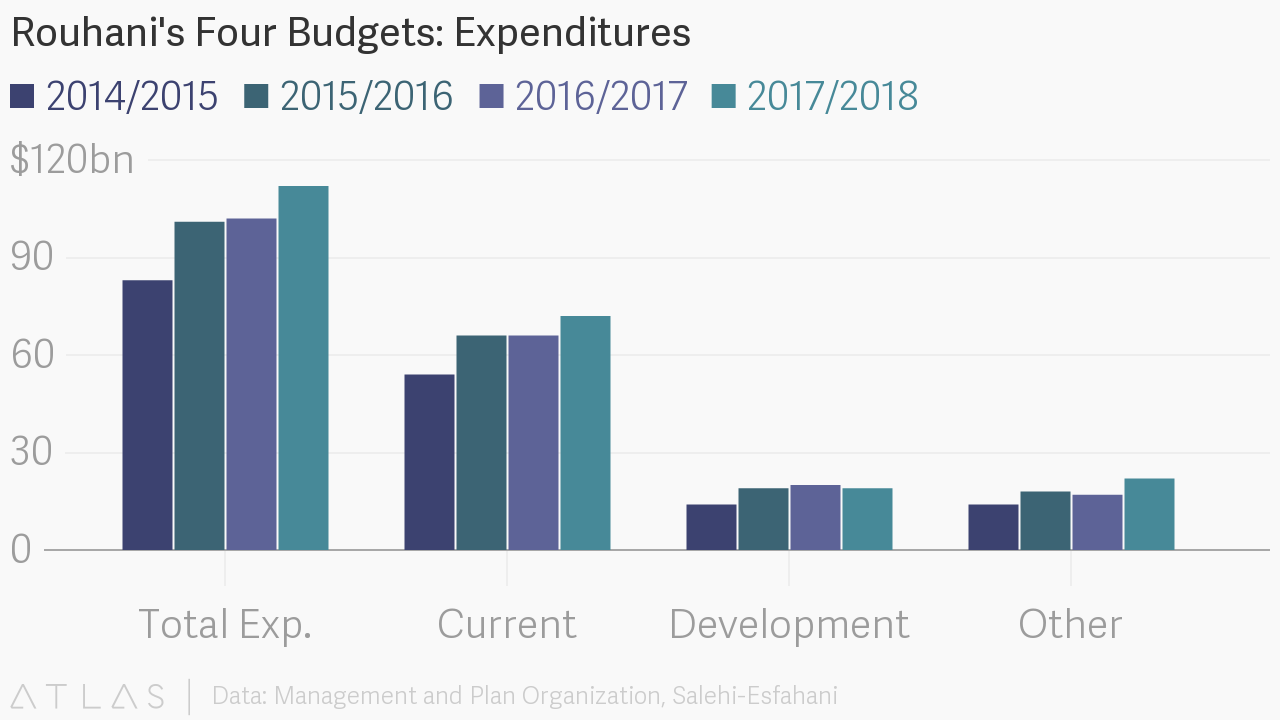

Some economists, including Djavad Salehi-Esfahani, have argued that Rouhani’s austerity economics are misguided, depriving the economy of vital liquidity that could help jumpstart investment and job creation. For example, Iran’s 2017/2018 budget sees tax revenues stay constant at an equivalent of USD 34 billion despite the fact that economic growth is expected to top 6%. Salehi-Esfahani believes that these figures reflect the Rouhani administration's belief “that letting the private sector off easy would encourage it to invest.” The government, meanwhile, will not contribute much more in investment. Development spending is set to decrease from USD 20 billion to USD 19 billion.

Surely, the Rouhani administration’s pursuit of a small government that leaves the burden of job creation and economic growth to the private sector is admirable. It represents a significant shift in the mentality that has characterized the economic policy of the Islamic Republic, which has long relied on state-owned enterprise and state-backed financing, supported by oil revenues, to drive economic growth.

But the volume of investment needed to revitalize economic sectors and create substantial job opportunity has not yet materialized. This is an undeniable fact, which Rouhani has attributed to failures on the part of Western powers to adequately implement sanctions relief, leaving international banks unable to work with Iran. Rouhani’s opponents meanwhile, attributed low volume of foreign direct investment to his administration's mismanagement. There is truth to both accounts.

In many ways, Rouhani’s lean towards austerity was a response to the spendthrift policies of his predecessor, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. The Ahmadinejad administration responded to faltering economic growth during a period of historic oil revenues by ploughing oil rents into the banking system and compelling banks to issue loans. These loans were often provided without the adequate due diligence and were used not to finance growth, but increasingly to fuel speculation, or more forgivably, to address cash flow difficulties faced by companies as a result of international sanctions.

As a result, Iran’s banking sector is now weighed down with a high proportion of non-performing loans, accounting for around 11% of total bank debt. When bank balance sheets grew increasingly precarious as non-payment of loans mounted in the sanctions period, competition for deposits grew. Exacerbating this competition, banks needed to provide higher deposits rates in order to stay ahead of inflation. The combination of forces pushed interest rates up to all-time highs.

The debt market in Iran is now broken. The IMF has urged urgent action to “restructure and recapitalize banks.” In the meantime, banks remain disinclined to lend and in the instances where healthier banks are able to provide loans, borrowers must contend with the high cost of debt.

This may help explain why the Rouhani administration so aggressively sought to address inflation—it was a necessary step to reduce the benchmark interest rate, which has so far been reduced from a high of 22% in 2014 to the current rate of 18%.

But even at such time that interest rates normalize, barriers will remain to the use of debt markets. At a structural level, Iranian companies, particularly in the private sector, rely on equity financing rather than debt financing in order to fund growth. This reflects a “bloc” behavior within Iranian enterprise. Partially as a consequence of the continued dominance of family-owned businesses in Iran’s non-state economy, business leaders tend to approach financiers within their own networks or holding groups, and many of Iran’s largest companies and banks anchor conglomerates that grew out of sequential processes of a kind of inward-looking venture capital. There is limited comfort among Iranian business leaders to seek funding from groups outside of these tight networks and by the same token, equity investors hesitate to provide finance projects outside their own networks. This means that the pool of available investor capital is rarely competing across the whole pool of available capital deployments—a significant inefficiency.

Growth-oriented investing itself can be a difficult strategic proposition. Iranian business leaders have understandably prioritized weathering periods of uncertainty over the execution of long-term plans. The challenge of dealing with short-term volatility has naturally favored short-term thinking. Major companies are only recently undertaking strategic reviews that might identify needs to invest in capital improvements or new services in order to drive growth in support of long-term goals.

The combination of the bloc effect in equity financing and the broken debt market creates a major brake on economic growth, especially from a supply-side perspective. To restore momentum, a third party is needed to order to reset the incentives and mechanisms around financing in Iran.

From the outset of its tenure, the Rouhani administration has hoped foreign investors would take on this role. An influx of foreign investment would have triggered growth without requiring the Rouhani administration to pursue difficult political gambles, such as expanding government expenditure for growth investments in the same period in which welfare programs are being culled. Moreover, the administration’s budgetary leeway was significantly reduced given the persistently low price of oil, making any such balancing act even more fraught.

Eighteen months after Implementation Day, it is clear that the administration significantly overestimated both the attractiveness of the market and underestimated the hesitation of major banks to resume ties with Iran. Investing in Iran is neither easily justified nor easily executed.

The country lacks two essential qualities that have characterized most emerging and frontier markets in the last decade. First, most emerging economies are not as diversified as Iran’s, and do not have such a large arrange of incumbent players with whom any foreign multinational or investor will need to compete for marketshare. There tend to be more “greenfield” opportunities in which lower capital commitment can generate higher returns. Second, a nearly universal feature among emerging markets is the consistent application of both expansionary monetary and fiscal policy. Such policy makes it possible for each investor dollar to achieve a higher return.

In its commitment to reduce interest rates and return the debt markets to normalcy, the Rouhani administration is pursuing an appropriate monetary policy—eventually lenders will become active again. But what remains perplexing is the insistence on austere government budgets in the face of low commitment from foreign investors.

It is clear that the Rouhani administration cannot easily spend tax and oil revenues on long-term projects. Oil revenues are stagnant and there is limited political will to raise taxes. At current levels of government revenue, the political risks of such expenditure are high; as the presidential election showed, populism remains a potent rallying cry among Iranian voters. But foreign investors can’t be expected to step into the gap. Direct equity investments remain a hard sell when domestic financing, whether in equity or debt form, remains throttled and liquidity challenges abound.

There is however a feasible solution that has seen much discussion, but little action—Iran’s return to international debt markets. A sovereign bond issue would both provide Iran’s government the opportunity to raise expenditures in a way that does not draw from existing sources of state revenue by providing a wide class of investors exposure to Iran’s expected period of economic growth. Such a security, ultimately backed by the country’s oil revenues, would serve to mitigate perceptions of country risk for creditors.

In May of 2016, Iran’s finance minister Ali Tayebnia disclosed that discussions were taking place with Moody’s and Fitch over restoring Iran’s sovereign credit rating. One year later, the debt sale continues to be a point of discussion. Recently, Valliolah Seif, Governor of the Central Bank of Iran, commented that the country will issue debt “when [Iran] becomes certain that there is demand for [its] debt.”

Seif’s comments allude to the essential problem of Iran’s planned debt sale—marketing. In order to get Iranian bonds onto the market in any substantial way, the country would need the support of major international banks to serve as underwriters. But banks remain hesitant due to sanctions and political risks.

Turkey, a country which presents creditors significant political risk without mitigation of oil revenues, was able to raise USD $2 billion in a Eurobond sale in January of this year. The sale was underwritten by Barclays, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs and Qatar National Bank.

Iran, is fundamentally a more attractive investment opportunity than Turkey. But major banks remain hesitant to provide financial services to Iran. The Rouhani administration needs to make the sovereign debt sale a core focus of its dialogue with European and global counterparts, and insist on political and technical support in order to entice 2-3 major banks to come on board. In the same manner that the Joint-Commission oversees implementation of the Iran nuclear deal, a multidisciplinary working group needs to be formed to manage the implementation of the debt sale. With the right stakeholders engaged, one can a combination of early-mover banks from Europe, Russia, and Japan agreeing to underwrite the bond issue.

Encouragingly, the delays may have played to Iran’s favor. Emerging markets are just now beginning to rebound, and investors have driven sovereign debt sales to record highs. The Rouhani administration must seize this opportunity and move beyond the limitations of its present austerity economics.

Photo Credit: Wikicommons