As China-Led Bloc Heads to Samarkand, Leaders Struggle to Find Common Aims

Members of the China-led Shanghai Cooperation Organisation will meet later this week in Samarkand. But the assembled leaders may struggle to find common ground in the face of regional and global crises.

This week, Uzbekistan is hosting the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) in Samarkand. The two-day summit begins on September 15. The leaders of China, Russia, India, Pakistan, Iran and other member and observer states are expected to attend. It will be the first time since the 2019 summit in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, that leaders will meet face to face in the SCO format.

The upcoming summit in Samarkand aims to present the organisation as a stable, capable, and evolving bloc with the capacity to address regional and global crises. For the host nation, Uzbekistan, the summit is a chance to promote the “Spirit of Samarkand” and to encourage global cooperation over global competition.

For years, the Uzbek government has sought to deepen its relations with other SCO member states. Having the opportunity to host the summit cements Uzbekistan’s position as a valuable member of the SCO community and allows it to push its regional agenda forward. Connectivity, cooperation, and the promotion of regional stability are at the core of President Shavkat Mirziyoyev’s goals, outlined on the eve of the summit.

Iran Takes Next Membership Step

One of the most important events expected to take place during the summit is Iran’s signing of binding documents related to its admission as a full member of the organisation. Iran’s accession will mark only the third time since its founding in which the SCO has admitted a new member—India and Pakistan joined in 2017. While Iran’s membership will not become official for at least another year, the procedures for its full membership will commence at the summit. Iranian leaders have faced a long wait for admission—it has been 15 years since Iran formally applied to join the bloc.

Tehran views joining the SCO as an important diplomatic achievement. The SCO represents a platform for non-western alignment and provides a platform for negotiations on tangible security and economic projects with other member states. Taking Iran on board, however, does not automatically guarantee either significant immediate benefits for Iran or an increase in the bloc’s capacity to effectively address security and economic challenges facing Asia, particularly while Iran remains under US secondary sanctions.

Eyes on Afghanistan

The situation in Afghanistan has proved strategically important for all SCO members, and especially the Central Asian republics. Security and humanitarian issues in Afghanistan were discussed in a large international conference hosted by Uzbekistan in July.

Among the Central Asian states, Uzbekistan is the loudest supporter of a taking a proactive approach towards the Taliban. While there are clear political issues with the Taliban, the Uzbek government realises that the critical south-eastern infrastructure corridor runs through Afghanistan. Development of this route promises significant economic benefits for Uzbekistan. The Uzbek president has stated that the SCO “must share the story of its success with Afghanistan.” In other words, it is a task for all regional states to engage with Kabul, and this task may become a benchmark for the capacity of SCO as an organisation. However, Afghanistan must become stable and a reliable partner to allow for its own development, as well to enable regional infrastructure projects to advance.

Tajikistan has a fundamentally different view towards the regime now in charge in Kabul. Dushanbe remains highly critical of the Taliban, raising concerns regarding terrorism and the safety of the Tajik ethnic groups in Afghanistan. However, neither Mirziyoyev or Emomali Rahmon, his Tajik counterpart, wishes to see Afghanistan further destabilised. China, India, and Russia basically hold the same position. Most regional countries are facing security threats from the Islamic State Khorasan Province and its affiliated groups. To add to the worries of the Central Asian states, Pakistan, a major player in Afghanistan, has itself faced political turmoil in the past year following the ousting of Prime Minister Imran Khan.

A Russian Dilemma

Russian president, Vladimir Putin, will face a difficult task in presenting his country as a global power in the face of unsuccessful military operations in Ukraine and economic strains caused by sanctions. The countries of Central Asia have close economic ties to Russia and are suffering the inevitable consequences of Moscow’s isolation.

As most regional countries are engaged in efforts to find ways to mitigate the negative impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Moscow is expecting a not-so-warm welcome in Samarkand. Recently reported battlefield losses in Ukraine have incentivised some SCO member states to more forcefully resist Moscow's ongoing attempts to influence their foreign policy, including their aims and activities within the organisation.

The SCO is largely dominated by China rather than Russia, but Russia has long been seen as a key partner in shaping the bloc’s political and economic aims. But it appears that Russia’s future position and influence within the organisation will be increasingly determined by the priorities of other member states and not Moscow’s ambitions. Moreover, while Russia’s ties with China have been described as a “partnership with no limits” by Chinese officials, the upcoming summit will be the first time Xi and Putin meet in-person since the start of the Ukraine invasion. Their engagements on the side-line of the summit will be telling of the extent of the bilateral partnership, particularly within the framework of the SCO.

Struggling for Common Aims

According to the Uzbek foreign ministry, numerous agreements on cooperation in specific areas, ranging from digital security to climate change, are will be discussed at the summit. The SCO is also seeking to establish partnerships with countries outside its primary geographical core, namely with Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar, in an effort to further extend the bloc’s political reach.

Until now, the greatest advantage of the SCO was that the bloc did not impose strict rules or apply pressure to prevent its members from cooperation with non-member states, even those who may be perceived as adversaries to China and Russia. This flexibility has been particularly important for Central Asian states who maintain significant security and economic relations with the United States and Europe alongside their partnerships with China, Russia, and India—as required by their multi-vector foreign policies.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, however, that flexibility seems at risk. For example, Russian politician Nikolai Patrushev recently declared that military training provided by the United States to certain SCO members poses a threat to Russia. Such accusations will no doubt colour bilateral and multilateral engagements in Samarkand.

Issued at the end of the summit, the "Samarkand Declaration" will present "a comprehensive political declaration on the SCO's position on international politics, economy and a range of other aspects." To what extent the SCO will be able to accommodate its members' varied and even contradictory aims is a question yet to be answered. The Samarkand summit will convene an organisation still searching for its trajectory.

Photo: Wikicommons

The Optimistic Case for Biden and Iran

In Tehran and Washington alike, the impact of Biden’s election on US-Iran relations has been the subject of strategizing for months. Now, the Biden presidency is a real political fact.

“It’s over.”

So reads the November 8 headline of Hamshahri, one of the leading newspapers in Iran. The past four years have been brutal for ordinary Iranians. The Trump administration waged an economic war on Iran that exacerbated the political and social tensions endemic to the country. Iranians are hoping that the election of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris will enable a return to the optimism they experienced in the short period between the implementation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in January 2016 and the dismaying election of Donald Trump in November of the same year.

In a CNN op-ed published in September, Biden made clear his intention to “rejoin the [JPCOA] as a starting point for follow-on negotiations” so long as “Iran returns to strict compliance with the nuclear deal.” Here, Biden is accepting the basic premise of “compliance-for-compliance.” In response to Trump’s withdrawal from the nuclear deal, Iran has reduced its own commitments to the deal, particularly by increasing its levels of uranium enrichment beyond what is permitted by the JCPOA. These moves, which have dismayed the remaining parties to the agreement—France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Russia, and China—are nonetheless perceived as tactical and reversible. The administration of Iranian president Hassan Rouhani remains committed to the JCPOA and appears ready to welcome the U.S. back into the deal so long as the U.S. policymakers accept “to be held responsible for damages” caused to “the people of Iran” as a result of Trump’s withdrawal, while also providing “guarantees” that such an event would not be repeated. Notably, Iranian foreign minister Javad Zarif has described the stance of the Biden administration as “promising.”

Despite these encouraging statements by both the Biden camp and officials in the Rouhani administration, there is a remarkable degree of pessimism surrounding the prospect of a U.S. reentry to the JCPOA. These assessments highlight pressure, particularly from U.S. allies in the Middle East, to build on the nuclear deal and achieve diplomatic breakthroughs on issues such as regional security and Iran’s missile program. They also point to the ascendency of Iran’s hardliners, a loose coalition of politicians who savaged Rouhani and his moderate bloc as the nuclear deal faltered. The vocal anti-Americanism of these conservative politicians and their labeling of figures such as Rouhani and Zarif as either naïve or knowing traitors, has furnished dire predictions for the future of U.S.-Iran diplomacy under the hardline president expected to prevail in Iran’s elections next year.

In a recent piece, Ariane Tabatabai and Henry Rome seek to account for the likely victory of a hardliner president, arguing that “the United States shouldn’t rush to secure a deal in the hopes of shaping Iran’s domestic politics, or for fear that the window of opportunity will close.” They observe astutely that “the new administration shouldn’t assume that without Rouhani, diplomacy wouldn’t stand a chance.” Tabatabai and Rome explain that the next Iranian president “will almost certainly be more conservative,” but note that the decision to engage in diplomacy with the United States will not be the prerogative of this hardline figure. Rather, such decisions require “buy-in from the whole system.” So long as Iran’s national security interests would be advanced by negotiations, it is reasonable to expect a receptiveness to talks, even with the U.S.

According to Tabatabai and Rome, it follows that the new Iranian administration will “have no choice but to negotiate” with the U.S. principally because of the country’s weak economic position. But this assessment likely underestimates the ability of the Iranian economy to limp along under sanctions pressure—even for four or more years. Before the COVID-19 pandemic hit the country, the Iranian economy was already returning to growth despite two years under Trump’s maximum pressure sanctions. High inflation has emerged as the single most significant challenge facing Iranian policymakers, but as the case of Venezuela shows, even the most extreme circumstances of hyperinflation can prove insufficient to coerce policymakers to the negotiating table.

Trump’s national security advisor, Robert O’Brien, recently conceded that the administration was seeing diminishing returns from economic coercion, having imposed “so many sanctions” that there was little pressure to add. This view reflects the assessments of the U.S. intelligence community, which is developing a more sophisticated understanding of the Iranian economy and its adaptability to sanctions pressure. The takeaway is that Trump’s sanctions offer Biden no real leverage on Iran and that it will not be possible to coerce Rouhani nor his successor into talks.

Despite this, Tabatabai and Rome are still correct to claim that Biden will have a shot at diplomacy—a very good one at that. To understand why, it is important to look beyond Trump’s withdrawal from the nuclear deal as the critical political act of the last three years. Far more significant is the fact that Iran remains in the agreement. Sure, Iran has reduced its compliance with key aspects of the deal. But the extraordinary political price paid by the Rouhani administration, spurred by a creditable commitment to diplomacy for its own sake and also by the strategic considerations of the wider Iranian “system,” suggests that understanding the logic of Iran’s persistence with the deal is the key to understanding the prospects for U.S.-Iran talks.

Back in 2018, on the eve of John Bolton’s appointment to lead the National Security Council, it appeared that the writing was on the wall for the Iran deal. As I wrote at the time, “by any conventional assessment, then, the Iran deal is dead.” Implementation of the deal was already faltering, and Bolton was hellbent on killing the agreement outright. But I foresaw a different outcome, arguing that “the Iran deal cannot be killed” because of a set of “several undeniable truths about Iran and its place in the world.” My argument focused on three structural factors that underpin Iran’s diplomatic engagement: the geopolitical influence of Iran, the demographic and economic drivers of the Iranian policy of engagement, and the fact that the United States has limited leverage because there is no credible or affordable military threat behind diminishing sanctions pressure.

Each of these structural factors is even more pronounced today. The Islamic Republic is less isolated diplomatically than ever before because it opted to remain in the JCPOA following the U.S. withdrawal. In the face of reduced oil revenues, the Iranian economy is more dependent on economic diversification, including in its trade partnerships. The combination of sanctions overuse and the American public’s calls for a pullback from the Middle East will leave Biden with less scope to coerce or threaten Iran.

The notion that Iran’s commitment to engagement (and the nuclear deal) is structural was underscored in a November 3 speech by Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei. Addressing the possible impact of U.S. elections on U.S.-Iran relations, Khamenei stated, “We follow a sensible, calculated policy which cannot be affected by changes of personnel.” Many took the statement to be Khamenei’s way of pouring cold water on the prospect of a Biden victory revitalizing the JCPOA. But again, in the Iranian assessment, the deal is not yet dead. The calculated policy to which Khamenei is referring is the policy of keeping the nuclear deal alive in accordance with Iran’s strategic interests.

This structural commitment means that the Biden administration does not need to rush to make a deal with Iran—the window of opportunity will not close when Iran elects a new president next summer. However, that does not mean Biden will not need to make some early gestures to signal the depth of his own commitment to diplomacy. In an excellent report envisioning a roadmap for the Biden administration’s reengagement of Iran, Ilan Goldenberg, Elisa Catalano Ewers, and Kaleigh Thomas, point to the importance of an early “de-escalation” phase, stating that the Biden administration “should start with immediate, modest unilateral confidence-building measures” in order to achieve both compliance-for-compliance on the nuclear file and “calm-for-calm” when it comes to regional tensions.

As Edoardo Saravalle has convincingly argued, the Biden administration can use executive orders to implement its sanctions relief commitments under a compliance-for-compliance framework in under sixty days. These moves can be made tangible by coordinating moves with European allies and international bodies to deliver tangible economic benefits to Iran. For example, this coordination can ensure that sanctions relief enables the unfreezing of foreign exchange reserves and the provision of Iran’s requested COVID-19 relief loan by the International Monetary Fund—moves that would ease inflation, delivering appreciable economic relief for ordinary Iranians. Should the Biden administration choose incentivization over coercion and thereby prove itself a credible counterparty for follow-on negotiations by the time of the Iranian election in the early summer of 2021, it is more than likely that any Iranian president elected—even a so-called hardliner—will take up the mantle of new talks.

The fierce opposition of hardliners to the nuclear deal was far more about the stakes of domestic politics than the terms of the deal itself. Even before talks had concluded, hardline politicians were gripped by anxiety that the successful implementation of the nuclear deal would grant Rouhani, a savvy political operator, a diplomatic and economic triumph that would consolidate the dominance of reformist politics in Iran for a generation. The opposition to the nuclear deal, which extended to efforts to undermine the deal itself, was intended to take Rouhani from the heights of popularity—he won two stunning mandates in high-turnout elections—to the depths of disgrace. The hardliners succeeded in this cynical mission and Rouhani was battered. But tellingly, the nuclear deal, as a product of Iran’s largely apolitical strategic decision-making, has survived.

A hardline president in Iran can be confident of his ability to run the country for an initial four-year term without needing a détente with Biden. The economy will limp along, regional tensions will remain high, and domestic unrest will simmer. But the presidential administration will be able to coordinate with state organs to keep Iran resilient to external and internal pressure—even as the Iranian people continue to suffer from the country’s stagnation.

But what president would choose to preside over a constant slow-moving crisis, particularly one that was not of his own making? For hardliners, 2021 represents an extraordinary political opportunity. For the first time since 1989, Iran and the United States will have first-term presidents at the same time. Meanwhile, Iran’s conservative politicians are increasingly concerned about the political legacy and legitimacy of the Islamic Revolution as it enters its fifth decade. Negotiations with the Biden administration offer Iran’s next president, and his political backers, the opportunity to give to the Iranian people that long-awaited gift—a robust, transformational deal with the world powers, chief among them the United States.

The impact of Biden’s election on U.S.-Iran relations has been the subject of strategizing for months. Today, what was once a hypothetical has become a reality. The impetus for U.S.-Iran talks arises from both an emergent political opportunity and the unchanged structural factors that push both sides towards engagement. The mechanics and sequencing of an American reentry into the JCPOA remain to be determined, but it will not be harder than when the deal was originally struck, when taboos needed to be broken in Tehran and Washington alike. Much has been learned over the last four years about what it takes to implement an “Iran Deal” successfully. We ought to be optimistic about comes next.

It’s a beginning.

Photo: Wikicommons

Europe Can Preserve the Iran Nuclear Deal Until November

After a humiliating defeat at the U.N. Security Council, Washington will seek snapback sanctions to sabotage what’s left of the nuclear deal. Britain, France, and Germany can still keep it alive until after the U.S. election.

By Ellie Geranmayeh and Elisa Catalano Ewers

The United States just lost the showdown at the United Nations Security Council over extending the terms of the arms embargo against Iran. The U.S. government was left embarrassingly isolated, winning just one other vote for its proposed resolution (from the Dominican Republic), while Russia and China voted against and 11 other nations abstained.

But the Trump administration is not deterred: In response to the vote, President Donald Trump threatened that “we’ll be doing a snapback”—a reference to reimposing sanctions suspended under the 2015 nuclear deal from which the United States withdrew in 2018.

The dance around the arms embargo has always been a prelude to the bigger goal: burning down the remaining bridges that could lead back to the 2015 deal.

The Trump administration now seeks to snap back international sanctions using a measure built into the very nuclear agreement the Trump White House withdrew from two years ago. This latest gambit by the Trump administration is unsurprisingly contested by other world powers.

On the one hand, Russia and China are making a technical, legal argument against the U.S. move, namely that the United States forfeited its right to impose snapback sanctions once it exited the nuclear deal. This is based on Security Council Resolution 2231 that enshrined the nuclear agreement, which clearly outlines that only a participant state to the nuclear deal can resort to snapback. This is a legal position that even former U.S. National Security Advisor John Bolton—an opponent of the nuclear deal and under whose watch Trump left the agreement—has recently endorsed.

In the end, however, this is more a political fight than a legal one. The political case—which seems to be most favored by European countries—is that the United States lacks the legitimacy to resort to snapback since it is primarily motivated by a desire to sabotage the multilateral agreement after spending the last two years undermining its foundations.

The main actor that will decide the fate of the nuclear deal after snapback sanctions is Iran itself. Iran has already acted in response to the U.S. maximum pressure campaign, from increasing enrichment levels and exceeding other caps placed on its nuclear program, to attacking U.S. forces based in Iraq and threatening to exit the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty.

But the calculations of decision-makers in Tehran will be influenced by the political and practical realities that follow snapback sanctions. And here, the response from the remaining parties to the nuclear deal—France, the United Kingdom, Germany, China, and Russia—will be critical. These countries remain committed to keeping the deal on life support—at least until the U.S. presidential election in November.

Seizing on its failure to extend the arms embargo, the United States now claims it can start the clock on a 30-day notification period, after which U.N. sanctions removed against Iran by the nuclear deal are reinstated. This notification will be timed deliberately to end before October—when the arms embargo is set to expire, and also when Russia takes over presidency of the U.N. Security Council: a time when Washington could face more procedural hurdles.

What is likely to follow snapback is a messy scene at the U.N. in which council members will broadly fall into three groups. First, the United States will seek to build support for its case—primarily through political and economic pressure—so that by the end of the 30-day notice period some U.N. member states agree to implement sanctions. The Trump administration will likely use the threat of U.S. secondary sanctions, as it has done successfully over the last 18 months, if governments don’t move to enforce snapback sanctions.

Even if most governments around the world disagree that the United States has any authority to impose snapback sanctions, some countries may be forced to side with Washington given the threat that the United States could turn its economic pressure against them.

The second group will be led by China and Russia, both of which have already started to push back. Not only will this group refuse to implement the U.N. sanctions that the U.S. government claims should be reimposed, but they likely will throw obstacles into the mix, such as blocking the reinstitution of appropriate U.N. committees that will oversee the implementation of such sanctions. This group may also see it as advantageous to seek a determination by the International Court of Justice on the legal question over the U.S. claim.

The third grouping will be led by the France, Britain, and Germany, who remain united in the belief that the deal should be preserved to the greatest extent possible. In a statement in June, the three governments already emphasized that they would not support unilateral snapback by the United States. But it is unclear if this will translate into active opposition—and their approach will certainly not include the obstructionist moves that Russia and China may make.

This bloc will look to stall decisions to take the steps necessary to implement the U.N. sanctions. This is a delicate undertaking, as European countries are not in the habit of blatantly ignoring the binding framework of some of the U.N.’s directives, and will want to balance their actions against the risk of eroding the security council’s credibility further. But they will also take advantage of whatever procedural avenues are in place to delay full enforcement of the sanctions, buying time to urge Iranian restraint in response to the U.S. moves.

Countries such as India, South Korea, and Japan are likely to favor this approach. These governments may even go so far as to send a significant political signal to Iran and back a joint statement by most of the security council members vowing not to recognize unilateral U.S. snapback sanctions.

As part of this approach, the 27 member states of the European Union could embark on a prolonged consultation process over how and if to implement snapback sanctions. The separate EU-level sanctions targeting Iran’s nuclear program are unlikely to be reimposed so long as Iran takes a measured approach to its nuclear activities.

Reimposing EU sanctions against Iran will entail a series of steps, the first of which requires France, Britain, and Germany, together with the EU High Representative, to make a recommendation to the EU Council. The return of EU sanctions would then require unanimity among member states, a goal which will take time to achieve in a context where Washington is largely viewed as sabotaging the nuclear deal.

In this process, the EU should seek to preserve as much space as possible to salvage the deal and avoid the reimposition of nuclear-focused sanctions against Iran—at least until the outcome of the U.S. election is clear. The U.K., in the run-up to Brexit, may well lean toward a similar position rather than tying itself too closely to an administration in Washington that may be on its way out.

Until now, the remaining parties to the nuclear deal have managed to preserve the deal’s architecture despite its hollowing out. The aim has been to stumble along until the U.S. election to see if a new opening is possible to resuscitate the agreement with a possible Biden administration in January.

While a Trump win could spell the end of the deal and further dim the prospects of diplomacy between the United States and Iran, the two sides could come to a new understanding over Iran’s nuclear program at some point during the second term that is premised on the original deal. Judging by the pace of the Trump administration’s nuclear diplomacy with North Korea, this will be a Herculean process with no certain outcome.

In Tehran, there will be some sort of immediate response to the snapback—most likely involving further expansion of its nuclear activities. However, Iran may decide to extend its strategic patience a few weeks longer until the U.S. election. A legal battle by Russia and China against snapback, combined with non-implementation of U.N. sanctions by a large number of countries and continued hints from the Biden camp that Washington would re-enter the nuclear deal could provide the Rouhani administration with enough face-saving to stall the most extreme responses available to Iran.

But with Iranian elections coming in the first half of 2021, there will be great domestic pressure from more hardline forces to take assertive action, particularly on the nuclear program, to give Iran more leverage in any future talks with Washington.

If Iran takes more extreme steps on its nuclear activities, such as a major increase in its enrichment levels or reducing access to international monitors, it will make it nearly impossible for the Britain and the EU to remain committed to the deal in the short term. There are also factors outside Iranian and U.S. control that could have an impact, such as a potential uptick in Israeli attacks against Iranian nuclear targets.

Over the course of the Trump administration, Europe and Iran have managed to avert the collapse of the nuclear deal. Having come so far, and just 11 weeks away from the U.S. election, they will need to work hard to prevent the total collapse of the agreement. Even if Biden—who has vowed to re-enter the deal if Iran returns to compliance—is elected, the remaining parties will need to continue the hard slog to preserve it until January.

Those opposed to the nuclear deal with Iran may see the last two months of a Trump administration as a window to pursue a scorched-earth policy toward Iran’s nuclear program. That leaves Britain and Europe with the job of holding what remains of the deal together, for as long as they can.

Ellie Geranmayeh is a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. Follow her at @EllieGeranmayeh.

Elisa Catalano Ewers is an adjunct senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security and a former U.S. State Department and National Security Council official.

Photo: IRNA

Iran Is Becoming Immune to US Pressure

Trump’s so-called maximum pressure campaign has empowered hard-line figures in Tehran, marginalizing those eager to take the diplomatic route.

By Sina Toosi

U.S. President Donald Trump said on June 5 that Iran should not wait until after the presidential election “to make the Big deal,” but can get a “better deal” with him now. Trump’s remarks came after a recent prisoner swap, which saw detained U.S. Navy veteran Michael White released from Iran in exchange for Iranian American doctor Majid Taheri. However, while Trump may want to negotiate with Iran and reinforce his self-avowed reputation as a deal-maker before the U.S. election, his “maximum pressure” policy has all but eliminated the chance for U.S.-Iranian diplomacy in the months to come.

Iran has proven resilient in the face of U.S. pressure. While many ordinary Iranians are suffering, the economy is not in total free fall, as many in Washington hoped for. Instead, the country has shown signs of economic recovery, with domestic production and employment increasing. According to Iran’s Central Bank chief Abdolnaser Hemmati, Iran’s nonoil gross domestic product grew by 1.1 percent last year. Prominent Iranian economist Saeed Laylaz also contends that Iran’s economy can weather the coronavirus pandemic and may experience growth this year despite the virus.

Trump’s bellicose rhetoric and actions have not made Iran more inclined to do a deal, but they have undermined any Iranian officials who supported negotiations with the United States. Whether wittingly or not, Trump’s policy decisions have closed the potential for diplomacy. The political cost one faces in Tehran for arguing in favor of negotiations is now simply too high. This is evident in how Iranian officials have reacted to the recent prisoner exchange.

Ali Shamkhani, the secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, one of the highest decision-making bodies in Iran, said in response to Trump’s offer for a deal, “The exchange of prisoners is not the result of negotiations & no talks will happen in the future.” Shamkhani’s remarks reflect a consistent line in Tehran: Negotiations with the United States are off the table. Even moderate President Hassan Rouhani’s foreign minister, Javad Zarif, and spokesperson Ali Rabiee now maintain that prisoner swaps can occur without negotiations.

The situation was different just a few months ago. The only other time the United States and Iran exchanged prisoners under the Trump administration was in December 2019, when Iran released Princeton doctorate student Xiyue Wang for Iranian scientist Masoud Soleimani. Unlike the recent White-Taheri exchange, the December swap also saw high-level meetings between U.S. and Iranian officials, a rare instance of bilateral U.S.-Iranian talks under the Trump administration. The United States has called for such a meeting again, but Iranian officials now accuse it of sabotaging diplomatic efforts.

Rouhani’s rhetoric around the time of the December swap also suggested he was more open to a new round of negotiations with the United States. Rouhani explicitly declared in the lead-up to the swap that Tehran had not ruled out talks and that negotiations could be “revolutionary.”

Then, in late December, Rouhani traveled to Japan in a trip that Japanese media said was greenlighted by Washington. There was speculation that the trip could have led to a “small deal” between the United States and Iran, with Iranian media reporting that Japan could get a U.S. waiver for importing Iranian oil and release billions of dollars in frozen Iranian oil revenues. Such a deal could have built confidence and met Rouhani’s precondition of sanctions removal for negotiating with Trump.

However, any hope that the positive diplomatic momentum built in late 2019 would lead to diplomatic progress between the United States and Iran was crushed in early January, with the U.S. assassination of Iranian military commander Qassem Suleimani. Many millions thronged Iran’s cities calling for revenge after the killing. Rouhani defiantly exclaimed in February: “They thought that with maximum pressure they can take us to the table of negotiation in a position of weakness … this will never happen.”

The political climate in Iran has since decisively turned hostile to any talk of negotiating with the United States, reestablishing a taboo that existed for years before the nuclear negotiations during the presidency of Barack Obama.

“Negotiations and compromise with America, the focal point of global arrogance, are useless and harmful,” said Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, Iran’s new parliamentary speaker, in his first speech to the body, “Our strategy toward the terroristic America is to complete our vengeance for the blood of the martyr Suleimani.”

Ghalibaf, a former commander in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and an old friend of Suleimani, unsuccessfully ran against Rouhani in both Iran’s 2013 and 2017 presidential elections. He assumed his parliamentary post in May, after parliamentary elections in February that swept conservatives to power. Importantly, that conservative victory occurred amid record-low turnout in the election and the widespread disqualification of reformist and moderate candidates by the Guardian Council.

Nevertheless, the total capture of parliament by conservatives cements the marginalization of reformists such as Rouhani and his allies that began after Trump scuttled the 2015 nuclear deal. Rouhani had sunk all his political capital into negotiating the accord and promised it would give the Iranian people major economic dividends.

Ghalibaf has now replaced Rouhani’s ally Ali Larijani as parliamentary speaker. Meanwhile, the judiciary, considered one of the three branches of government in Iran alongside the presidency and legislature, is being run by Rouhani’s other former 2017 rival, conservative cleric Ebrahim Raisi.

The changing political winds are significant for the future of Iranian foreign policy. Within the byzantine Islamic Republic system, Rouhani managed to forge necessary consensus on negotiations with the United States during the Obama administration, which included nods of approval from both the Supreme National Security Council and the supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Unlike his hard-line predecessor, the boisterous and belligerent Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Rouhani formed a cabinet of many U.S.-educated technocrats and his ambitions laid squarely on securing Iran’s economic integration to the world. For a time, Rouhani was riding high in public opinion polls, but that has dramatically reversed.

Ghalibaf, while not as aggressively ideological as Ahmadinejad, has made it clear that he will do everything in his power to ensure Rouhani remains a lame duck for the rest of his presidency. In his first address as parliamentary speaker, he lambasted Rouhani’s administration for its “focus on the outside [world]” and not believing in “the principles of jihadi management.”

Ironically, Ghalibaf himself has been described as a technocrat, drawing from his 12-year run as mayor of Tehran. During his tenure, he oversaw the construction of major infrastructure projects, voiced support for the nuclear deal, and participated in international summits such as the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, where in 2008 he called for international investment in Iran.

However, political expediency compels Ghalibaf to oppose Rouhani for the rest of his term, which ends next year. As parliamentary speaker, Ghalibaf presides over disparate conservative factions, ranging from the fundamentalist Front of Islamic Revolution Stability to the free-market-oriented Islamic Coalition Party. Targeting Rouhani and his agenda is an easy and effective way for Ghalibaf to unite conservatives behind him. Above all, the goal will be to obstruct Rouhani’s ability to negotiate with the United States and restore the political fortunes of his camp.

Trump is mistaken if he believes “maximum pressure” is getting him closer to a deal with Iran. The policy is not leading to Iran’s capitulation or collapse, but entrenching U.S.-Iran hostilities and keeping the United States perennially at the cusp of war in the Middle East. Trump, who ran in 2016 on getting the United States out of costly Middle Eastern wars, nearly went to war last June and again in January over his decision to escalate with Iran.

An alternative approach is possible but requires Trump to ditch maximum pressure and rebuild the trust necessary for successful negotiations. International relations and the real estate market are not similar. Bullying and bluster do not win deals; mutual respect and “win-win” compromise do. Trump has styled himself as a deal-maker, but ahead of the November election he has zero foreign-policy victories to his name. If he wants any semblance of a positive foreign-policy legacy, he needs to get off the path to war and on a path to negotiations with Iran.

Sina Toossi is a senior research analyst for the National Iranian American Council. Follow him at @SinaToossi.

Photo: IRNA

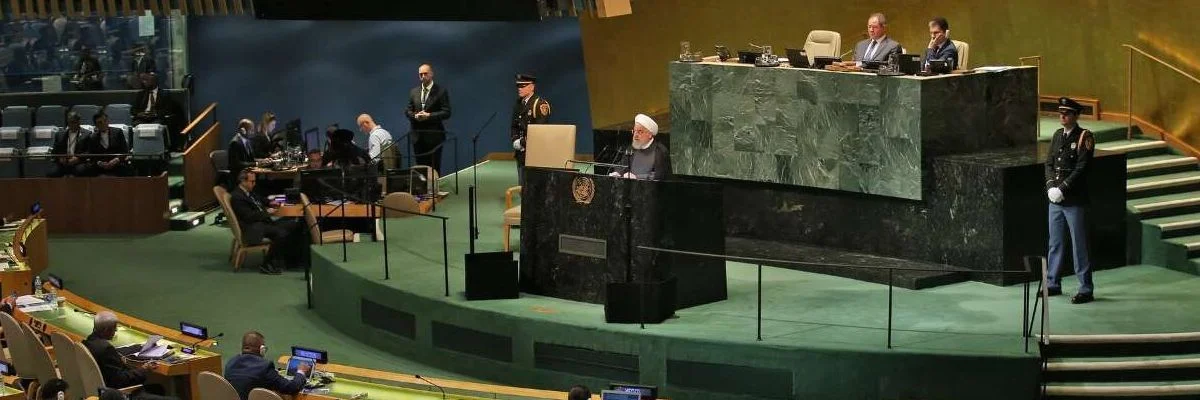

Full Remarks Made by the Iranian President at the United Nations

◢ The prepared remarks of Iranian President Hassan Rouhani delivered at the United Nations General Assembly on September 25, 2019. They are published here in full in the interest of providing fuller insight into Iran’s intended message on the potential for diplomacy with the United States.

Editor’s Note: The following are the prepared remarks of Iranian President Hassan Rouhani delivered at the United Nations General Assembly on September 25, 2019. The remarks, which have not been checked against delivery, were provided by the Permanent Mission of the Islamic Republic of Iran to the United Nations. They are published here in full in the interest of providing fuller insight into Iran’s intended message on the potential for diplomacy with the United States.

In the name of God, the Most Compassionate, the Most Merciful

Mr. President

I would like to congratulate your deserved election as the president of the seventy-fourth General Assembly of the United Nations and wish success and good luck for Your Excellency and the honorable Secretary General.

At the outset, I should like to commemorate the freedom-seeking movement of Hossein (PBUH) and pay homage to all the freedom-seekers of the world who do not bow to oppression and aggression and tolerate all the hardship of the struggle for rights, as well as to the spirits of all the oppressed martyrs of terrorist strikes and bombardment in Yemen, Syria, Occupied Palestine, Afghanistan and other countries of the world.

Ladies and Gentlemen

The Middle East is burning in the flames of war, bloodshed, aggression, occupation and religious and sectarian fanaticism and extremism; And under such circumstances, the suppressed people of Palestine are the biggest victim. Discrimination, appropriation of lands, settlement expansions and killings continue to be practiced against the Palestinians.

The US and Zionist imposed plans such as the deal of century, recognizing Beit-ul Moqaddas as the capital of the Zionist regime and the accession of the Syrian Golan to other occupied territories are doomed.

As against the US destructive plans, the Islamic Republic of Iran’s regional and international assistance and cooperation on security and counter-terrorism have been so much decisive. The clear example of such an approach is our cooperation with Russia and Turkey within the Astana format on the Syrian crisis and our peace proposal for Yemen in view of our active cooperation with the special envoys of the Secretary General of the United Nations as well as our efforts to facilitate reconciliation talks among the Yemen parties which resulted in the conclusion of the Stockholm peace accord on HodaydaPort.

Distinguished Participants

I hail from a country that has resisted the most merciless economic terrorism, and has defended its right to independence and science and technology development. The US government, while imposing extraterritorial sanctions and threats against other nations, has made a lot of efforts to deprive Iran from the advantages of participating in the global economy, and has resorted to international piracy by misusing the international banking system.

We Iranians have been the pioneer of freedom-seeking movements in the region, while seeking peace and progress for our nation as well as neighbors; and we have never surrendered to foreign aggression and imposition.We cannot believe the invitation to negotiation of people who claim to have applied the harshest sanctions of history against the dignity and prosperity of our nation. How someone can believe that the silent killing of a great nation and pressure on the life of 83 million Iranians arewelcomed by the American government officials who pride themselves on such pressures and exploit sanctionsin an addictive manner against a spectrum of countries such as Iran, Venezuela, Cuba, China and Russia. The Iranian nation will never ever forget and forgive these crimes and criminals.

Ladies and Gentlemen

The attitude of the incumbent US government towards the nuclear deal or the JCPOA not only violates the provisions of the UN Security Council Resolution 2231, but also constitutes a breach of the sovereignty and political and economic independence of all the world countries.

In spite of the American withdrawal from the JCPOA, and for one year, Iran remained fully faithful to all its nuclear commitments in accordance with the JCPOA. Out of respect for the Security Council resolution, we providedEurope with the opportunity to fulfill its 11 commitments made to compensate the US withdrawal. However, unfortunately, we only heard beautiful words while witnessing no effective measure. It has now become clear for all that the United States turns back to its commitments and Europe is unable and incapable of fulfilling its commitments. We even adopted a step-by-step approach in implementing paragraphs 26 and 36 of the JCPOA. And we remain committed to our promises in the deal. However, our patience has a limit; When the US does not respect the United Nations Security Council, and when Europe displays inability, the only way shall be to rely on national dignity, pride and strength. They call us to negotiation while they run away from treaties and deals. We negotiated with the incumbent US government on the 5+1 negotiating table; however, they failed to honor the commitment made by their predecessor.

On behalf of my nation and state, I would like to announce that our response to any negotiation under sanctions is negative. The government and people of Iran have remained steadfast against the harshest sanctions in the past one and a half years ago and will never negotiate with an enemy that seeks to make Iran surrender with the weapon of poverty, pressure and sanction.

If you require a positive answer, and as declared by the leader of the Islamic Revolution, the only way for talks to begin is return to commitments and compliance.

If you are sensitive to the name of the JCPOA, well, then you can return to its framework and abide by the UN Security Council Resolution 2231. Stop the sanctions so as to open the way for the start of negotiations.

I would like to make it crystal clear: If you are satisfied with the minimums, we will also convince ourselves with the minimums; either for you or for us. However, if you require more, you should also pay more.

If you stand on your word that you only have one demandfor Iran i.e. non-production and non-utilization of nuclearweapons, then it could easily be attained in view of the IAEA supervision and more importantly, with the fatwa of the Iranian leader. Instead of show of negotiation, you shall return to the reality of negotiation. Memorial photo is the last station of negotiation not the first one.

We in Iran, despite all the obstructions created by the US government, are keeping on the path of economic and social growth and prosperity. Iran’s economy in 2017, registered the highest economic growth rate in the world. And today, despite fluctuations emanating from foreign interference in the past one and a half years, we have returned to the track of growth and stability. Iran’s gross domestic product minus oil has become positive again in recent months. And the trade balance of the country remains positive.

Distinguished Participants

The security doctrine of the Islamic Republic of Iran is based on the maintenance of peace and stability in the Persian Gulf and providing freedom of navigation and safety of movement in the Strait of Hurmoz. Recentincidents have seriously endangered such security. Security and peace in the Persian Gulf, Sea of Oman and the Strait of Hormuz could be provided with the participation of the countries of the region and the free flow of oil and other energy resources could be guaranteed provided that we consider security as an umbrella in all areas for all the countries.

Upon the historical responsibility of my country in maintaining security, peace, stability and progress in the Persian Gulf region and Strait of Hormuz, I should like to invite all the countries directly affected by the developments in the Persian Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz to the Coalition for Hope meaning Hormuz Peace Endeavor.

The goal of the Coalition for Hope is to promote peace, stability, progress and welfare for all the residents of the Strait of Hormuz region and enhance mutual understanding and peaceful and friendly relations amongst them.

This initiative includes various venues for cooperation such as the collective supply of energy security, freedom of navigation and free transfer of oil and other resources to and from the Strait of Hormuz and beyond.

The Coalition for Hope is based on important principles such as compliance with the goals and principles of the United Nations, mutual respect, equal footing, dialog and understanding, respect to territorial integrity and sovereignty, inviolability of international borders, peaceful settlement of all differences, rejection of threat or resort to force and more importantly two fundamental principles of non-aggression and non-interference in the domestic affairs of each other. The presence of the United Nations seems necessary for the creation of an international umbrella in support of the Coalition for Hope.

The Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Islamic Republic of Iran shall provide more details of the Coalition for Hope to the beneficiary states.

Ladies and Gentlemen

The formation of any security coalition and initiative under any title in the region with the centrality and command of foreign forces is a clear example of interference in the affairs of the region. The securitization of navigation is in contravention of the right to free navigation and the right to development and wouldescalate tension, and more complication of conditions and increase of mistrust in the region while jeopardizing regional peace, security and stability.

The security of the region shall be provided when American troops pull out. Security shall not be supplied with American weapons and intervention. The United States, after 18 years, has failed to reduce acts of terrorism; However, the Islamic Republic of Iran, managed to terminate the scourge of Daesh with the assistance of neighboring nations and governments. The ultimate way towards peace and security in the Middle East passes through inward democracy and outward diplomacy. Security cannot be purchased or supplied by foreign governments.

The peace, security and independence of our neighbors are the peace, security and independence of us. America is not our neighbor. This is the Islamic Republic of Iran which neighbors you and we have been long taught that: Neighbor comes first, then comes the house. In the event of an incident, you and we shall remain alone. We are neighbors with each other and not with the United States.

The United States is located here, not in the Middle East. The United States is not the advocate of any nation; neither is it the guardian of any state. In fact, states do not delegate power of attorney to other states and do not give custodianship to others. If the flames of the fire of Yemen have spread today to Hijaz, the warmonger should be searched and punished; rather than leveling allegations and grudge against the innocence. The security of Saudi Arabia shall be guaranteed with the termination of aggression to Yemen rather than by inviting foreigners. We are ready to spend our national strength and regional credibility and international authority.

The solution for peace in the Arabian Peninsula, security in the Persian Gulf and stability in the Middle East should be sought inside the region rather than outside of it. The issues of the region are bigger and more important than the United States is able to resolve them. The United States has failed to resolve the issue in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria, and has been the supporter of extremism, Talibanism and Daeshism. Such a government is clearly unable to resolve more sophisticated issues.

Distinguished Colleagues

Our region is on the edge of collapse, as a single blunder can fuel a big fire. We shall not tolerate the provocative intervention of foreigners. We shall respond decisively and strongly to any sort of transgression to and violation of our security and territorial integrity. However, the alternative and proper solution for us is to strengthen consolidation among all the nations with common interests in the Persian Gulf and the Hormuz region.

This is the message of the Iranian nation:

Let’s invest on hope towards a better future rather than in war and violence. Let’s return to justice; to peace; to law, commitment and treaty and the negotiating table. Let’s come back to the United Nations.

Photo: IRNA

The United States and Iran are in a Quantum War

◢ It took just under an hour for staff at Israel’s Government Press Office to delete a tweet that suggested that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had finally decided to wage war on Iran. The conflict Iran faces today is neither a hot war nor a cold war. It is a quantum war—a superimposition of two states of conflict. Put another way, depending on when you observe the facts, Iran is both at war and it is not.

It took just under an hour for staff at Israel’s Government Press Office to delete a tweet that suggested that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had finally decided to wage war on Iran. The office replaced that tweet with another one that clarified that Israel merely seeks to join with Arab nations to “combat Iran.” The most striking thing about the whole fiasco was not that the prime minister was agitating for war. It was that the English word in the original translations seemed so precise and unambiguous: war.

There was a kind of refreshing clarity to the translation that has been elusive in Iran policy, particularly as articulated by the Trump administration. Donald Trump has placed sanctions on Iran ostensibly as an alternative to military confrontation, but he still refers to the sanctions program as part of an “economic war.” The administration creates exemptions for humanitarian trade but ensures that they are not operable. Officials declare their unwavering support for the Iranian people, but bar them from entering the United States under the “Muslim Ban.” The U.S. government devises covert programs to sabotage Iran’s defensive capabilities but then leaks their existence to the press.

Fittingly, Netanyahu’s mistranslation fiasco came during a summit that Trump administration officials insisted was “not a trash-Iran conference.” Yet the prime minister himself assured reporters that the meeting was focused on Iran.

At first glance these might just seem like the hallmarks of the Trump administration’s chaotic, incoherent, and hypocritical policymaking. But perhaps these contradictions are the basis of a new kind of warfare. The conflict Iran faces today is neither a hot war nor a cold war. It is a quantum war—a superimposition of two states of conflict. Put another way, depending on when you observe the facts, Iran is both at war and it is not.

Iran has been stuck in a kind of liminal space of international relations for four decades. But the international community and Iran’s domestic political constituencies now face an unprecedent number of internal divisions over the question of Iran’s place in the world.

Whereas Iran once counted on the support of Russia and China and the relative ambivalence of the Arab states to head off a multilateral challenge from the United States and Europe, today, the United States joins the Arab states and Israel to form a nascent coalition against Iran. These anti-Iranian actors seem principally united by a shared perception of Iran’s threat expressed in increasingly ideological terms. Lacking political legitimacy, such a coalition can neither marshal the kind of containment required for a cold war nor credibly engage in a hot war. What is left is quantum war.

In some respects, this is the worst circumstance for Iran. Whereas hot and cold wars tend to unite people in the country under attack, a quantum war is politically more insidious. Some Iranians believe the nuclear deal is still viable and channels of dialogue with Europe still open, so they remain committed to diplomacy. Others focus on airstrikes from Israel and terrorist attacks abetted by Arab governments, and therefore see no alternative to conflict. According to the 2019 worldwide threat assessment from the director of national intelligence, as a result of such dynamics, “regime hardliners will be more emboldened to challenge rival centrists by undermining their domestic reform efforts and pushing a more confrontational posture toward the United States and its allies.” The Iranian public is equally divided. Today half of Iranians support the nuclear deal, while half do not.

In response to such domestic pressures, Iran has once again returned to hedging on matters related to its foreign relations. In the same week that President Hassan Rouhani announced his willingness to negotiate with the United States should it “repent,” Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei declared that when it comes to the United States, “no problem can be solved.”

The quantum war also poses dilemmas for Europe, which finds itself struggling to craft a coherent policy. A recent statement from the foreign affairs council of the European Union inelegantly sought to warn Iran on its role in Syria, its ballistic missile activities, and its role in assassination plots on European soil while also boasting of the extraordinary efforts being made to sustain bilateral trade in the face of U.S. secondary sanctions. The contradictions do not merely exist on paper. Divisions are increasing not just among EU member states but also within foreign ministries about the right pathway on Iran. Depending on whom you ask, Iran is either a possible regional partner or an incorrigible regional proliferator. Of course, disagreement, debate, and compromise are part of effective policymaking. But at the same time, the European response to the quantum war increasingly resembles quantum diplomacy.

When Erwin Schrödinger devised his famous “Schrödinger Cat” thought experiment to describe the phenomenon of superimposed states, he used a term apt for discussions of foreign policy: verschränkung, or “entanglement.” In the context of quantum mechanics, entanglement occurs “when two particles are inextricably linked together no matter their separation from one another.” Moreover, “although these entangled particles are not physically connected, they still are able to share information with each other instantaneously.”

Few concepts could better describe the quantum war between the United States and Iran, separated by space, but linked in time, signaling their intentions with the immediacy of tweets.

Photo Credit: IRNA

Mohammad Javad Zarif: Iran Sees a Broken U.S. Foreign Policy

◢ In a wide ranging essay, Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif outlines the Iranian view of a “broken” U.S. foreign policy and details Iran’s 15 demands in response to the 12 demands issued by U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo after the withdrawal from the JCPOA.

This piece was originally published in Iran Daily. It is republished here with permission.

Following the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Paris Climate Accord, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) is the third multilateral agreement that the current United States administration has withdrawn from. The administration has also put in jeopardy other multilateral arrangements such as NAFTA, the global trade system, and parts of the United Nations system, thus inflicting considerable damage to multilateralism, and the prospects for resolving disputes through diplomacy.

The announcement on 8 May 2018 of United States’ withdrawal from the JCPOA and the unilateral and unlawful re-imposition of nuclear sanctions—a decision opposed by majority of the American people—was the culmination of a series of violations of the terms of the accord by this administration, in spite of the fact that the International Atomic Energy Agency, as the sole competent international authority had repeatedly verified Iran’s compliance with its commitments under the accord. The US decision was rejected by the international community and even its closest allies, including the European Union, Britain, France and Germany.

On 21 May 2018, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, in a baseless and insulting statement, issued a number of demands and threats against Iran in brazen contravention of international law, well-established international norms, and civilized behavior. His statement reflected a desperate reaction by the US administration to the overwhelming opposition of the international community to the persistent efforts by the White House to kill the JCPOA, and the ensuing Washington’s isolation. Mr. Pompeo, in his statement, attempted to justify the US’ withdrawal from the JCPOA and divert international public opinion from the unlawful behavior of the United States and its outright violation of UN Security Council resolution 2231; a resolution drafted and proposed by the US itself and adopted unanimously by the Council. Mr. Pompeo’s 12 preconditions for Iran to follow are especially preposterous as the US administration itself is increasingly isolated internationally due to its effort to undermine diplomacy and multilateralism. It comes as no surprise that the statement and the one made by the US president on Iran were either ignored or received negatively by the international community, including by friends and allies of the United States. Only a small handful of US client states in our region welcomed it.

I seriously doubt that had the US Secretary of State even had a slight knowledge of Iran’s history and culture and the Iranian people’s struggle for independence and freedom, and had he known that Iran’s political system—in contrast to those of the American allies in the region—is based on a popular revolution and the people’s will, would he have delivered such an outlandish statement. He should, however, know that ending foreign intervention in Iran’s domestic affairs, which culminated in the 25-year period following the US-orchestrated coup in 1953, had always been one of the Iranian people’s main demands since well before the Islamic Revolution. He should also be aware that in the past 40 years the Iranian people have heroically resisted and foiled aggressions and pressures by the US, including its coup attempts, military interventions, support of the aggressor in an 8-year war, imposition of unilateral, extraterritorial and even multilateral sanctions, and even going as far as shooting down an Iranian passenger plane in the Persian Gulf in 1987. “Never forget” is our mantra, too.

The Islamic Republic of Iran derives its strength and stability from the brave and peace-loving Iranian people; a people who, while seeking constructive interaction with the world on the basis of mutual respect, are ready to resist bullying and extortions and defend in unison their country’s independence and honor. History bears testimony to the fact that those who staged aggression against this age-old land, such as Saddam and his regime’s supporters, all met an ignominious fate, while Iran has proudly and vibrantly continued its path towards a better and brighter future.

It is regrettable that in the past one-and-a-half years, US foreign policy—if we can call it that—including its policy towards Iran has been predicated on flawed assumptions and illusions—if not actual delusions. The US President and his Secretary of State have persistently made baseless and provocative allegations against Iran that constitute blatant intervention in Iran’s domestic affairs, unlawful threats against a UN Member State, and violations of the United States’ international obligations under the UN Charter, the 1955 Treaty, and the 1981 Algiers Accord. While rejecting these fictitious allegations, I would like to draw the attention of US policymakers to some aspects of their nation’s current foreign policy that are detrimental to the entire international community:

First- Impulsive and illogical decisions and behavior of the US President—and efforts by his subordinates to find some justification to persuade a reluctant domestic and foreign audience—have already surfaced as the main feature of the decision-making process in Washington over the past 17 months. This process, coupled with ill-conceived and hasty explanations to justify outcomes, usually lead to contradictory statements and actions. As an example, in his role as CIA Director, Mike Pompeo once in a Congressional hearing emphatically stated: “Iran has not violated its commitments.” Later, and following the US President’s decision to withdraw from the accord, now Secretary of State Pompeo in his statement on May 21 emphatically stated that “Iran has violated its commitments."

Second- It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that some aspects of US foreign policy have been put up for auction—far beyond the routine lobbying practices. It is, for instance, unprecedented that a US president should choose the very country he had called “fanatic and a supporter of terrorism” during his election campaign as the destination for his first foreign visit as president, or to publicly make aspects of his foreign policy positions contingent on the purchase by one or another country of arms and other items from the United States. It has also been reported that in some other cases, mostly illegitimate financial interests have been the main basis for the formulation of mind-bogglingly ill-conceived US policy positions.

Third- Contempt for international law and attempts to undermine the rule of law in international relations have been among the main features of the current administration’s foreign policy. To the extent, according to media reports, that the US negotiators in the G7 Summit were even insisting on deleting the phrase “our commitment to promote the rules-based international order.” This destructive approach began by showing contempt for the fundamental principle of pacta sunt servanda, which is arguably the oldest principle of international law. The US withdrawal from some international agreements and undermining others, coupled with efforts to weaken international organizations, are examples of destructive moves so far by the US government, which have unfortunately darkened the outlook for the international order. Obviously, the continuation of such policies can endanger the stability of the international community, turning the US into a rogue state and an international outlaw.

Fourth- Predicating decisions on illusions is another aspect of this administration’s foreign policy. This has been especially evident with respect to West Asia. The illegal and provocative decision regarding al-Quds al-Sharif, blind support for the cruel atrocities committed by the Zionist regime against Gazans, and aerial and missile attacks against Syria are some of the more brazen aspects of such an unprincipled foreign policy.

The statement made by Mr. Pompeo on May 21 was the culmination of a delusional US approach to our region. Ironically, the US Secretary of State tried to set preconditions for negotiations and agreement with the Islamic Republic of Iran at a time when the international community is doubtful about the possibility or utility of negotiation or agreement with the US on any issue. How can the US government expect to be viewed or treated as a reliable party to another round of serious negotiations following its unilateral and unwarranted withdrawal from an agreement which was the result of hundreds of hours of arduous bilateral and multilateral negotiations, in which the highest ranking US foreign affairs official participated, and which was submitted to the Security Council by the US and adopted unanimously as an international commitment under Article 25 of the Charter?

Recent statements and actions by the US president, including reneging on his agreement with the G7 while in the air flying back from the summit, are other examples of his erratic behavior. His remarks immediately following his meeting with the leader of the DPRK regarding his possible change of mind in 6 months are indicative of what the world is facing—an irrational and dangerous US administration. Does the US Secretary of State really expect Iran to negotiate with a government whose president says: “I may stand before you in six months and say, ‘Hey, I was wrong. I don’t know if I’ll ever admit that, but I’ll find some kind of an excuse”? Can such a government really set preconditions for Iran? Isn’t it actually confusing the plaintiff for the defendant? Mr. Pompeo has forgotten that it is the US government that needs to prove the credibility of its words and legitimacy of its signature, and not the party that has complied with its international obligations and sticks to its word. In fact, the truth is that all US administrations in the past 70 years should be held accountable for their disregard for international law, and their violations of bilateral and multilateral agreements with Iran. A short list of the rightful demands of the Iranian people from the US government could include the following:

1. The US government must respect Iran’s independence and national sovereignty and assure Iran that it will end its intervention in Iran’s domestic affairs in accordance with international law in general, and the 1981 Algiers Accord in particular.

2. The United States must abandon its policy of resorting to the threat or use of force – which constitute a breach of the preemptory norms of international law and principles of the Charter of the United Nations—as an option in the conduct of its foreign affairs with or against the Islamic Republic of Iran and other States.

3. The US government should respect the state immunity of the government of the Islamic Republic of Iran, which is a fundamental principle of international law, and, while rescinding previous arbitrary and unlawful financial judgments, it should refrain from executing them in the US and extraterritorially.

4. The US government should openly acknowledge its unwarranted and unlawful actions against the people of Iran over the past decades, including inter alia the following, take remedial measures to compensate the people of Iran for the damages incurred, and provide verifiable assurances that it will cease and desist from such illegal measures and refrain from ever repeating them:

a. Its role in the 1953 coup that led to the overthrow of Iran’s lawful and democratically-elected government and the subsequent 25 years of dictatorship in Iran;

b. Unlawful blocking, seizure and confiscation of tens of billions of dollars of assets of the Iranian people after the Islamic revolution, or under various baseless pretexts in recent years;

c. Direct military aggression against Iran in April 1980, which was a blatant violation of the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Iran;

d. Provision of massive military and intelligence assistance to the Iraqi dictator during the 8-year war he imposed on the Iranian people inflicting hundreds of billions of dollars of damages on Iran and its people;

e. Responsibility in the enormous suffering that Iranians have incurred over the past 3 decades as a result of the use by Saddam of chemical weapons, whose ingredients were provided by the US and some other western countries;

f. The shooting down of an Iran Air passenger plane by the USS Vincennes in July 1988—a flagrant crime that led to the murder of 290 innocent passengers and crew, and the subsequent awarding of a medal to the captain of the ship rather than punishing him for his war crime;

g. Repeated attacks against Iran’s oil platforms in the Persian Gulf in the spring of 1988;

h. Repeated and unwarranted insults against the Iranian people by calling the entire nation “an outlaw and rogue nation” or “a terrorist nation” and by including Iran in the so-called “axis of evil;”

i. Unlawful and unreasonable establishment of a bigoted list of the nationals of some Islamic countries, including Iranians, prohibiting their entry into the US. The Iranians are among the most successful, educated and law-abiding immigrants in the US and have done great service to American society. They are now prohibited from seeing their loved ones, including even their aging grandparents;

j. Harboring and providing safe haven to anti-Iranian saboteurs in the USA, who openly incite blind violence against Iranian civilians, and supporting criminal gangs and militias and terrorist organizations, some of which were listed for years as terrorist groups by the US and later removed from the list following intense lobbying by those who have received money from them. Some of those lobbyists now occupy high-ranking positions in the Trump administration;

k. Support provided to Mossad for the multiple terrorist assassinations of Iranian nuclear scientists;

l. Sabotage of Iran’s nuclear peaceful program through cyber-attacks;

m. Fabrication of fake documents to deceive the international community over Iran’s peaceful nuclear program and to create an unnecessary crisis.

5. The United States government must cease its persistent economic aggression against the Iranian people which has continued over the past four decades; nullify the cruel and extensive primary and extraterritorial sanctions, rescind hundreds of legislations and executive orders aimed at disrupting Iran’s normal development which are in flagrant contravention of international law and have been universally condemned, and compensate the Iranian people for the enormous damages to the Iranian economy and its people.

6. The US government should immediately cease its violations and breaches of the JCPOA, which have caused hundreds of billions of dollars in direct and indirect damages for disrupting trade with and foreign investment in Iran, compensate Iranian people for these damages and commit to implement unconditionally and verifiably all of its obligations under the accord, and refrain (in accordance with the JCPOA) from any policy or action to adversely affect the normalization of trade and economic relations with Iran.

7. The US government should release all Iranians and non-Iranians who are detained under cruel conditions in the US under fabricated charges related to the alleged violation of sanctions, or apprehended in other countries following unlawful pressure by the US government for extradition, and compensate for the damage inflicted on them. These include pregnant women, the elderly and people suffering from serious health problems; some of whom have even lost their lives in prison.

8. The US government should acknowledge the consequences of its invasions and interventions in the region, including in Iraq, Afghanistan and the Persian Gulf region, and withdraw its forces from and stop interfering in the region.

9. The US government should cease policies and behavior that have led to the creation of the vicious DAESH terrorist group and other extremist organizations, and compel its regional allies to verifiably stop providing financial and political support and armaments to extremist groups in West Asia and the world.

10. The US government should stop providing arms and military equipment to the aggressors—who are murdering thousands of innocent Yemeni civilians and destroying the country—and cease its participation in these attacks. It should compel its allies to end their aggression against Yemen and compensate for the enormous damage done to that country.

11. The US government should stop its unlimited and unconditional support for the Zionist regime in line with its obligations under international law; condemn its policy of apartheid and gross violations of human rights, and support the rights of the Palestinian people, including their right to self-determination and the establishment of an independent Palestinian State with al-Quds al-Sharif as its capital.

12. The US government should stop selling hundreds of billions of lethal—not beautiful—military equipment every year to regions in crisis, especially West Asia, and instead of turning these regions into powder kegs it should allow the enormous amount of money spent on arms to serve as funding for development and combating poverty. Only a fraction of the money paid by US arms customers could alleviate hunger and abject poverty, provide for potable, clean water, and combat diseases throughout the globe.

13. The US government should stop opposing the efforts by the international community for the past 5 decades to establish a zone free from weapons of mass destruction in the Middle East. It should compel the Zionist regime—with its history of aggression and occupation—to de-nuclearize, thus neutralizing the gravest real threat to regional and international peace and security, which emanates from the most destructive arms in the hands of the most warmongering regime in our time.

14. The US government should stop increasingly relying on nuclear weapons and the doctrines of using nuclear weapons to counter conventional threats—a policy that is in flagrant contravention of its commitment under Article VI of the Non-Proliferation Treaty, the advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice, the 1995 NPT Review Conference Declaration, and UN Security Council resolution 984. The US should comply with its moral, legal and security obligations in the field of nuclear disarmament, which is a near unanimous demand of all United Nations Member States, and virtually all people across the globe, including even former US Secretaries of State. As the only State that is stamped with the shame of ever using nuclear weapons itself, it is incumbent on the US to relieve humanity from the nightmare of a global nuclear holocaust, and give up on the illusion of security based on “mutually assured destruction” (MAD).

15. The US government should once and for all commit itself to respect the principle of pacta sunt servanda (agreements must be kept), which is the most fundamental principle of international law and a foundation for civilized relations among peoples, and discard in practice the dangerous doctrine which views international law and international organizations as merely “a tool in the US toolbox.”

The aforementioned US policies are examples of what has resulted in Iranians distrusting the American government. They are also among underlying causes of injustice, violence, terrorism, war and insecurity in West Asia. These policies will bring about nothing but a heavy toll in human lives and material assets for different regions of the world, and isolation for the US in world public opinion. The only ones benefiting are and will be lethal arms manufacturers. If the US government summons the courage to renounce these policies in words and deeds, its global isolation will end and a new image of the US will emerge in the world, including in Iran, paving the path to joint efforts for security, stability, and inclusive sustainable development.