SIPRI Has Revised Four Years of Data on Iran's Military Spending

SIPRI has corrected its data on Iran’s military spending, applying a more relevant exchange rate for dollar conversions. Instead of ranking as the 14th largest military spender in the world in 2021, Iran was actually ranked 39th.

SIPRI—the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute—has just published its “Yearbook” for 2022. The flagship annual publication offers civilian and military leaders around the world a way to compare military spending between countries and to gauge which countries are investing in greater military power.

Last year, I identified a major problem with the data about Iran’s military spending. The 2021 Yearbook estimated Iran’s military spending at $24.6 billion, a total that put it just above Israel in the rankings, as the 14th largest military spender in the world. This did not make sense.

Iran’s military, while posing a threat within the region, does so primarily because of inexpensive missile and drone systems and heavy reliance on proxy forces. Iran’s military lacks the kinds of advanced aircraft, armour, and other systems that are typically found in the arsenals of the world’s top military spenders.

A closer examination of the SIPRI data, and communication with SIPRI’s researchers, revealed that the Swedish think tank had been using the wrong exchange rate to convert Iran’s local currency military expenditures into dollar values. The researchers were using the “official” central bank exchange rate, which has for several years been a subsidised exchange rate used exclusively for the import of essential goods.

This common mistake has been rectified. SIPRI researchers note in the 2022 Yearbook dataset that they are using the NIMA exchange rate to convert to dollars, which results in a far better estimate of the Iranian state’s true purchasing power. The historical data has been corrected going back to 2018.

The impact of the correction is significant. The revised figures mean that instead of ranking as the 14th largest military spender in the world in 2021, Iran was actually ranked 39th. In 2022, spending totalled $6.8 billion. That is a mere fraction of the military spending of regional rival Saudi Arabia, which spends an estimated $75 billion. Iran even spends less on its military than regional minnow Kuwait.

SIPRI should be commended for making this correction. But in certain respects, the damage has been done. For several years their data was used to suggest that Iran posed a much greater threat to regional and global security than it truly did. A significant number of authoritative publications and news reports relied upon the SIPRI data to put Iran’s military spending in context and unfortunately used the inflated dollar totals published between 2018 and 2021. Those inflated figures conformed to a pervasive and convenient narrative—this may explain why the issue went unresolved for so long.

Photo: IRNA

SIPRI Has Overstated Iran's Military Spending For Years

SIPRI produces the world’s most authoritative data on global military expenditure and the arms trade. But for years they have been overstating the size of Iran’s military budget.

SIPRI—the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute—produces the world’s most authoritative data on global military expenditure and the arms trade. The SIPRI Yearbook, a flagship annual publication, offers civilian and military leaders around the world a way to compare military spending between countries and to gauge which countries are investing in greater military power.

This year, the SIPRI Yearbook includes some significant statements about Iran’s military expenditure—which is estimated at $24.6 billion. In a factsheet summarising key trends, SIPRI’s researchers declared “Iran increased its military spending by 11 percent, making it the 14th largest military spender in 2021. This is the first time in 20 years that Iran has ranked among the top 15 military spenders.”

We are accustomed to thinking about Iran as a major military spender because we frequently hear about the country’s military, its missile programme, and its nuclear weapons ambitions. But on closer examination, SIPRI’s figures for Iran do not add up.

Iran is a country that is under the most significant sanctions programme in the world and its economy has stagnated for a decade. But SIPRI’s data suggests that Iran is spending even more than Israel, ranked 15th in the world with $24.4 billion in military expenditure in 2021. The comparison with Israel—a country in which the military is constantly procuring the most advanced military equipment in the world, including from foreign manufacturers—is clarifying. If Iran were indeed spending even more money, what could it possibly be spending all that money on? Iran produces nearly all its military hardware domestically, has basically no heavy armour, no modern air force, no modern naval fleet, and few advanced weapons systems. The country’s defence is primarily assured by a ballistic missile programme, which while impressive, is not a programme that costs nearly $25 billion to operate.

So where did SIPRI go wrong? The answer is simple and reflects a common mistake made by researchers who rightly want to put Iranian financial data into a comparative framework. To produce global rankings and to make data on military spending comparable over time, SIPRI converts local currency expenditures into US dollars. In 2021, SIPRI calculated Iran’s total expenditure in local currency at IRR 1033 trillion. In an email exchange, a SIPRI researcher clarified for me that SIPRI defines military expenditure using the following formula:

Military expenditure = Ministry of Defence and Armed Forces Logistics Total + Armed Forces General Staff Total + Artesh Joint Staff Total + Sepah Joint Staff (IRGC) Total + Armed Forces Social Security Organization Total

This is a reasonable formulation and corresponds to how Iranian sources calculate military spending. So there is no reason to doubt SIPRI’s calculation of military spending in local currency terms.

For most countries, the next step in the analysis involves finding the average dollar exchange rate for the given year and dividing the total expenditure by that figure. But Iran does not have a single exchange rate and SIPRI’s researchers picked the wrong one. Over the years, they have relied upon data for Iran’s official dollar exchange rate published by the World Bank and sourced from the Central Bank of Iran. This was also confirmed in my email exchange with the SIPRI researcher. On face, this seems like the right approach—SIPRI is using an “official” rate from an authoritative source. But in Iran, the official exchange rate does not reflect market prices. It is a subsidised exchange rate that is only used for the importation of certain essential commodities, such as wheat and medicine. Since 2019, the official exchange rate has been capped at IRR 42,000. This is the rate that SIPRI mistakenly used to calculate Iran’s total military expenditure for 2021.

The exchange rate that ought to have been used is the exchange rate defined within the government budget itself. The Iranian government balances its budget by relying in part on foreign exchanges revenues, principally earned through the sale of oil. Prior to the budget for the Iranian calendar year 1395, which was submitted in November 2015, the official exchange rate was indeed the reference rate used in the budget. But after several years of sanctions pressure, the Central Bank of Iran could no longer prop up the value of the currency. So while the official exchange rate was kept low as a means to subsidise the purchase of key imports, a separate exchange rate was defined in the budget. The rates have diverged dramatically since.

Each budget includes a revenue target from the sale of oil and a target volume of oil sales. By comparing these two numbers with the price of oil fixed in the budget, it is possible to arrive at the dollar exchange rate on which the budget depends. This exchange rate, which we can call the budget exchange rate, expresses how many rials the Iranian government estimates it can spend for each dollar it earns. It is therefore a much better exchange rate to use when trying to account for different levels of purchasing power between countries when it comes to government expenditure.

For the draft budget in the Iranian calendar year 1401, which was submitted in November 2021 and forms the basis of SIPRI’s 2021 expenditure estimate, the budget exchange rate was IRR 230,000—a rate five times higher than the IRR 42,000 official rate. In other words, SIPRI’s 2021 yearbook overstates Iran’s military spending by a factor of five. Using the budget exchange rate, Iran’s total military expenditure is just $4.5 billion, a total that places Iran outside of the Top 40 military spenders in the world. The below chart compares the military expenditures reported by SIPRI using the official exchange rate and expenditures calculated according to the budget exchange rate.

In the last few years, annual inflation in Iran has been as high as 40 percent, leading to a sharp increase in nominal expenditures. But by using the official exchange rate, which has been capped since 2019, SIPRI has failed to account for the impact of inflation on relative prices between the dollar and rial. In some respects, this is a surprising mistake for the researchers to make, as analysts of Iran’s military expenditures have warned about the difficulty of pinning down real expenditures given Iran’s topsy-turvy economy. In 2018, Jennifer Chandler, a researcher at IISS noted that in “large increases in local currency, impressive as they might seem, do not necessarily reflect an over-prioritisation of the regime on defence spending.”

Another way to examine whether Iran is spending more on its military is to simply convert from nominal to real spending in the local currency, avoiding the pitfalls represented by the exchange rate. To do so, we can deflate the nominal military spending using Consumer Price Index data published by the Central Bank of Iran. This analysis reveals that Iran’s military spending has been flat for two decades, just barely keeping up with inflation.

The Iranian government does take its defence seriously. But it has developed the means to ensure that defence cheaply by focusing on specific capabilities such as ballistic missiles and drones and by relying on proxies as part of a “forward defence” strategy. Iran’s military does not look like a military backed by $24.6 billion dollars of spending in a single year—where are the next generation fighters, battle tanks, and naval vessels? Yet, regional actors and Western governments continue to assess that the Iranian military poses a significant threat, even while real military expenditures have been flat. To put it another way, Iran has been able to maintain its military spending in the face of sanctions in part because it has long been parsimonious. This raises questions about the wisdom of trying to throttle Iran’s economy to address security threats.

The mistake SIPRI has made is understandable given the scope of the yearbook project and the difficulty of accounting for the peculiarities of each country’s economy. Yet, Iran is likely the country whose military spending is under the greatest international scrutiny, meaning that the impact of the mistake is profound. The exaggerated military expenditures unwittingly reported by SIPRI have reinforced the view of the Iranian military as especially large and threatening. The figures have also been used by a wide range of actors, including Iran’s regional rivals, to justify their own increases in military spending and the acquisition of advanced weapons systems. In this way, the presumed value of military spending has overshadowed the sober assessment of military capabilities. Encouragingly, SIPRI have told me they will “definitely investigate” the exchange rate issue. They will be forced to do so because of a planned change in Iran’s foreign exchange policy that will see the subsidised rate eliminated altogether during this budget year. But while a correction would be welcome, the damage has already been done.

Photo: IRNA

Eyeing Oil Revenues, Iran’s Public Sector Workers Demand Higher Wages

Iran’s public sector workers often mobilise during annual budget negotiations, a drawn-out process involving multiple state actors and institutions.

In its first 200 days in office, the Raisi administration has encountered massive labour mobilisations. In late January, medical personnel across the country’s hospitals and universities joined the picket line. In February, teachers reportedly staged demonstrations in over a hundred urban areas. Last month, pensioners and welfare beneficiaries rallied in more than a dozen major cities.

Motivated mostly by wage grievances, protestors have adopted a range of assertive slogans and demands. In one provincial city, teachers hung up a big banner that read: “Raisi, Qalibaf, this is the final message: the teachers’ movement is ready to revolt.” Pensioners called Raisi a “liar,” blamed his government for neglecting “the nation,” demanded an end to “oppression,” and called for the immediate release of political prisoners.

Commentators have lumped these labor protests together with other recent protest actions. A recent Financial Times report suggested that workers’ rallies and protests over water rights indicate growing popular discontent with the country’s economic record, leaders, and political institutions.

But these broad explanations fail to capture the undercurrents of the labour mobilisations of recent months. Iran’s economy has been doing poorly for years and dissatisfaction with the government is nothing new. It would also be wrong to assume that labour protests are motivated by general public dissatisfaction. In fact, most of the large and coordinated protests have been staged by a rather specific type of worker: state employees. These are relatively educated and privileged workers, employed in protected administrative and professional jobs in Iran’s state bureaucracy and civil service.

Protests by state employees need to be understood in the context of negotiations over the country’s annual budget. The annual budget, which sets wage levels across the public sector, is approved by the Iranian new year in late March. Workers often mobilise during annual budget negotiations, a drawn-out process involving multiple state actors and institutions. Sectoral and labour pressure tends to intensify when negotiations reach their final stages.

While budget-related protests are a routine occurrence, they have been especially widespread this year because workers are emboldened by the prospect of higher oil revenues. The international price of oil has spiked over the past months and state authorities have already revised projected oil revenues upward. Iran is also in advanced negotiations on the country’s nuclear programme, which may result in sanction relief, potentially unlocking billions of dollars in government income.

As employees of the Iranian state, public sector workers hope to benefit from these injections of oil money into Iran’s fiscal system. State employees are mobilising now in an attempt to lock in favourable spending commitments for the upcoming fiscal year. In 2014-2015, when Iran was in similarly advanced talks with the Obama administration over sanctions’ relief, public sector workers also mobilised in large numbers.

A final factor is the legitimacy of the Raisi government itself. Coming to power last year through manipulated elections and record low turn-out, Ebrahim Raisi has been eager to display himself as tolerant and understanding of the country’s impoverished urban middle classes. Raisi has tried to court Iran’s historically reformist-leaning middle classes to gain a degree of popular legitimacy and consolidate his tenuous leadership among various hardliner factions.

Teachers, pensioners, and nurses represent a bloc of reformist-leaning state employees that have coordinated protest actions over the past months. Rather than cracking down on their rallies, security forces have relied on containment and targeted repression—strategies which, so far, have not been successful in preventing further protests.

Teachers have staged by far the largest rallies, winning major concessions in the process. They began protesting right when Raisi came to power in August 2021. Nationwide strikes in November 2021 put pressure on parliament to finalise an expensive piece of employment law that teachers’ unions had long lobbied for. Emboldened by this legislative victory, teachers have continued to protest to make sure that the government allocates enough money to the program.

Teachers, pensioners, and nurses have long complained that government spending prioritises state employees in the armed forces, judiciary, police, and the security apparatus. Over the past months, the government has tried to address their concerns about pay discrimination by reigning in salary increases in these relatively privileged and conservative-leaning parts of the state.

Notably, in January, parliament rejected a bill on payroll spending in the judiciary. Judiciary workers and lawyers immediately responded by taking to the streets, angered by the fact that Raisi, their former boss and patron, had hit their interests so openly. The judiciary protestors argued that they too have a range of legitimate concerns, including having to rely on corruption and bribe-taking to top off their salaries.

In response, the head of the Administrative and Recruitment Organisation justified limiting spending on judiciary salaries by stating that it would “create dissatisfactions in other government bodies.” Mehdi Taghiani, a hardliner MP from Esfahan, made a similar claim. “Severe inflation over the past years has reduced the purchasing power of all workers, not just one specific group in the civil service. If we increase salaries in the judiciary, it will lead to a domino effect by which pay discrimination will eventually lead to the collapse of the government’s financial system,” he stated.

The Raisi government has tried to sell its fiscal policies as prudent and responsible to the outside world. Iran’s finance minister recently proclaimed that the country’s new budget “includes a number of structural reforms.” Such structural reforms, he explains, include “increasing the salaries of government employees at rates less than the inflation rate.”

Yet, the final budget, which was approved several days ago, shows little evidence that the government is committed to austerity and lowering labour costs across the board. The budget increases spending on education by 40 percent, almost double last year’s raise. The government also decided to increase the official minimum wage in the upcoming Persian year by over 50 percent, which will take its real value back to 2017 levels.

In a move away from austerity, the budget contains a variety of cuts and concessions that are part of Raisi’s strategy to mediate between various public sector demands while trying to win over sceptics and opponents. These policies will not only fail to address fundamental labour concerns, but internal rivalries and sectoral interests within the public sector will almost certainly continue to undermine labour solidarity. Teachers and judiciary personnel, for instance, have refused to express support for each other’s struggles. After the judiciary protests in early January, the Twitter feed of Mohammad Habibi, an outspoken leader of the largest teacher’s union, remained unusually quiet. Long-standing competition over the allocation of state resources have led to mutual suspicions will prove difficult to overcome.

Photo: IRNA

Iran’s Emboldened Workers Press New President for More Concessions

A wide range of social groups in Iran have been mobilising to express their socioeconomic grievances. Grappling with concessions made by the previous administration, Iran’s new president is on the back foot.

In the third week of September, teachers in dozens of towns and cities across Iran took to the streets, calling on the new president, Ebrahim Raisi, to fully implement existing labour laws. The authorities responded quickly and positively, promising to work on an implementation plan. But the teachers are not ready to back down. In an interview conducted for this article, a leader of the main teachers’ union said his organization will continue to use a “carrot and stick” approach to ensure that the Raisi administration makes good on its promises.

The latest nationwide demonstrations by teachers are part of a bigger protest wave that has gripped Iran over the past year. In the first few months of the year, pensioners mobilised in Tehran and other major cities. In July, residents of the southern province of Khuzestan protested water shortages. Between June and August, contract workers across Iran’s oil sector staged intermittent strikes and demonstrations. These protests are unlikely to let up. A wide range of social groups have been mobilising—organising locally, regionally, and nationally—to express socioeconomic grievances.

As these protests have continued, the Raisi administration has defied predictions that it would quickly impose order on Iran’s restless society. Raisi was elected president in June after extensive electoral manipulation and a record low turnout. But that Iran’s new leadership came to power with little regard for the electorate has not dissuaded protestors from making demands of state authorities. According to one protest tracker, September—Raisi’s first full month in office—saw one of the highest number of protest events in the past year.

Raisi has been forced to grapple with the promises made by his predecessor, Hassan Rouhani. Rouhani launched his first term with a vow to bring inflation under control and spend government resources prudently. He exited office last August having promised financial support to a wide range of groups and sectors. Rouhani’s commitment to inflation reduction was sincere and, initially, successful. After carefully and painstakingly negotiating sanctions relief and rebalancing the economy between 2013 and 2017, his successes were quickly undone by the twin shocks of the Trump administration’s reimposition of sanctions in May 2018 and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in February 2020. Realising that fiscal prudence would not be enough to shore the Iranian economy, Rouhani decided to direct spending towards his core constituents, namely the urban middle classes.

As Djavad Salehi-Isfahani has shown, Tehran and urban areas were largely spared the rapidly rising poverty rates seen in Iran’s rural communities after 2018. To prevent further slides in the incomes of pensioners and public sector teachers—two important middle class segments generally aligned with reformist politics—the Rouhani administration consistently increased the budget share allocated to education and social security. As Kevan Harris observes in a recent report, education and social security together accounted for over 55 percent of the 2021-2022 budget, up from less than 45 percent just four years earlier. The more the Rouhani administration intervened to support the welfare of key constituencies, the more groups such as teachers and pensioners became emboldened, increasing their demands as the deteriorating economic situation eroded their incomes. Protest activity grew despite the growing risk of state repression.

Still, Rouhani’s constituents suffered despite his targeted interventions. Public sector teachers saw their real wages fall by over 40 percent between March 2018 and March 2021. Middle class workers employed in the public sector suffered significantly as government spending ran out of steam. Private sector wage workers, such as those in the construction sector, have fared comparatively better as their wages rise with inflation.

Faced with discontented workers and limited fiscal space, the Raisi administration has sought to blame their predicament on Rouhani’s recklessness, rather than the deteriorating economic situation. Hardline politicians argue that Rouhani deliberately loaded up on financial commitments in his final days in office in order to put a stick in the spokes of the Raisi government. Parliament member Ahmad Hossein Falahi recently complained that “unfortunately in the final days of the Rouhani administration a lot of things got done. This is because the managers of the previous government aimed to impose a number of policies on the incoming administration, despite the fact that the Plan and Budget Organization was supposed to safeguard this year’s budget.” Falahi added that this has created a dangerous “mentality” whereby social groups invoke Rouhani’s generosity to bargain with the Raisi government.

It is true that in his final months in office, Rouhani made a number of concessions to protesting workers that seemed extraordinarily generous given the state’s emptied coffers. For example, striking oil workers won significant concessions right before Rouhani left office. Contract workers did most of the protesting and the Rouhani administration responded by forcing employers to increases wages for contractors. But Rouhani went further and also increased the salaries of more than 100,000 workers directly employed by the oil ministry. Promises were also made to improve working conditions.

Teachers were another group benefiting from extraordinary generosity in the final months of the Rouhani administration. The 2021-2022 annual budget, approved in spring, doubled the money allocated to the education ministry’s payroll costs. Given current inflation rates, this budget increase raises the wages of public sector teachers by a massive 25 percent in real terms—the largest one-year pay increase teachers have received in at least two decades. After years of resistance, the government also suddenly agreed to several other long-standing demands about job benefits.

Still, despite the accusations now being made, it more likely that an exhausted Rouhani administration, realising it would soon leave office, relaxed its commitment to austerity, submitting more easily to bottom-up pressure for increased spending. The Raisi administration is now faced with the difficult task of managing the fiscal obligations it has inherited. The choice facing Iran’s new president is whether to prioritise the demands of constituencies that have shown a capacity for sustained protest, or whether to redirect spending in favour of workers in the judiciary, police, and military who are among his core constituents. With next year’s budget negotiations coming up soon, Iranian workers have the government on the back foot.

Photo: IRNA

Iran's Government Falling into a Debt Trap of Its Own Making

◢ President Rouhani’s budget proposal for the upcoming Iranian year will see the government run a deficit amounting to about 10 percent of GDP or 60 percent of the state’s general budget, excluding oil revenues and withdrawals from the National Development Fund. Rather than increase tax collection to ease budget gaps, the Rouhani administration plans to tap Iran’s nascent debt markets to cover its public spending requirements.

President Rouhani’s budget proposal for the upcoming Iranian year will see the government run a deficit amounting to about 10 percent of GDP or 60 percent of the state’s general budget, excluding oil revenues and withdrawals from the National Development Fund.

Rather than increase tax collection to ease budget gaps, the Rouhani administration plans to tap Iran’s nascent debt markets to cover its public spending requirements. Rouhani’s cabinet intends to issue at least IRR 5 trillion government treasury bills and sukuk bonds in the next Iranian calendar year. For debts already nearing their maturity, it will have to repay close to IRR 3.3 trillion in 2019-20. The recourse to debt markets has economic commentators increasingly concerned over state’s ability to cover rising liabilities in the coming years.

The concern extends to the think tank of the Iranian parliament. Their assessment is that over the next four to five years Iran’s government debt may reach 50-70 percent of GDP, leaving little “fiscal space.” According to the Sixth Development Plan (2016-21), the government is required to keep government debt, including the debt of state-owned enterprises, at below 40 percent of GDP. But it looks likely that the government will exceed this level. Should Iran’s government debt exceed 70 percent of GDP, the fiscal position would be high-risk. Meanwhile, by 2021, interest charges on bonds will constitute 4 percent of GDP, while the total budget deficit is meant to remain below 3 percent of GDP according to parliamentary researchers.

Looking worldwide, high government debt is associated with financial crises. According to data from the OECD, two third of countries hit by the 2009 financial crises were those whose government debt-to-GDP ratio exceeded 60 percent.

When looking to the fraction of the total debt ratio, it is important to consider both the numerator and the denominator. The fact that government bonds in Iran offer 20 percent returns means that interest payments can quickly balloon. Unlike Japan or the United States where interest rates on government bonds are zero percent and 2.4 percent respectively, keeping tabs on fiscal space in Iran requires accounting for the cost of the debt to the government, not merely the amount of debt issued. ‘

Moreover, given that Iran has experienced limited economic growth in recent years and is poised to enter a recession, its fiscal space is expected to decrease. According to the study conducted by The Center for the Management of Debt and Financial Assets of Iran, this proportion was approximately 55.6 percent in 2015.

Putting aside the risks posed by the Rouhani governments turn to debt markets, it is worth asking whether there have been any clear macroeconomic benefits. In the assessment of parliament researchers, the Rouhani administration’s turn to debt markets is only sensible if increased government spending helps generate economic growth.

But with government revenues expected to stagnate, it is unlikely that Rouhani will have sufficient means to encourage the infrastructure projects and other investments to keep Iran’s economic growth at the 2.5 percent level experienced in the first six months of this Iranian year—particularly given the reimposition of US secondary sanctions.

Low or negative growth rates combined with the high interest rates of debt securities mean that the government’s insatiable appetite to underwrite its budget through bond markets may backfire, forcing the Central Bank of Iran to print more money to pay debts, exacerbating the cycle of inflation and devaluation to the detriment of the whole economy. To avoid such an outcome, the Rouhani government must match its turn to debt markets with an effort to expand the tax base.

Photo Credit: IRNA

Iran Budget Under Scrutiny As Oil Revenues Fall

◢ Next week, President Hassan Rouhani will submit a budget proposal for the forthcoming Persian year (covering March 2019-2020). Currently, the Rouhani administration has few options as it seeks to avoid a budget deficit. Yet the political tradeoffs required when devising a budget under sanctions may prove more difficult to manage than the economic challenges.

Next week, President Hassan Rouhani will submit a budget proposal for the forthcoming Persian year (covering March 2019-2020). The budget bill’s adherence to fiscal rules and the reasonableness of its estimates will be under intense scrutiny given the volatile political and economic climate in Iran.

Policymakers and business leaders see the budget as having four purposes: to maintain economic stability, to boost economic growth, to expand redistribution for poverty reduction, and to supply public goods. Given limited resources related to the reimpositon of sanctions, the Rouhani administration intends to focus on the latter two goals. For example, the administration is slated to earmark USD 14 billion of its hard-earned oil dollars to ease importation of a group of 25 items classified as basic goods and medications.

In the face of such emergency expenditures, the cabinet must carefully balance its budget to ensure that spending is kept in line with revenue, especially given the impact of sanctions on the contribution of oil revenues.

Assuming that Iran will continue to sell 1 million barrels per day (mbpd) of crude oil at USD 54 per barrel, total oil revenues next year will reach approximately USD 20 billion or about IRR 1,140 trillion, at the effective official exchange rate of IRR 57,000. More optimistically, if Iran can manage to keep exports around 1.5 mbpd, the state will earn USD 30 billion, or IRR 1,710 trillion.

According to Iran’s Sixth Development Plan, which establishes guidelines for government budgets and covers a five-year period from 2016, revenue estimates for oil and gas condensate exports cannot exceed a forecasted IRR 1,150 trillion by more than 15 percent. As such, the budget must technically be balanced based on oil revenues of IRR 1,300 trillion. A draft version of the budget places oil revenues at IRR 1,690 trillion, flouting the rule.

Moreover, the Sixth Development Plan mandates that 14.5 percent of oil revenues be allocated to the National Iranian Oil Company, 34 percent to the National Development Fund of Iran (NDFI) and 3 percent for investment in Iran’s underdeveloped regions. The remaining revenues are earmarked for use by the central government.

In an effort to increase its available resources, the Rouhani administration planned to cancel the allocation of oil revenues to NDFI. But Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, intervened to ensure NDFI secures at least a 14 percent allocation. When allocations are reduced, the government typically does not actually transfer the diverted revenue to the Central Bank of Iran, maintaining the funds outside of Iran. This means that the government is effectively printing money, adding inflationary pressure.

A further challenge for the Rouhani government will be that even if oil revenues can be sustained, sanctions will force the government to receive most of its foreign exchange earnings in currencies such as the Indian Rupee, Iraqi Dinar, Turkish Lira and Chinese Yuan. These funds, deposited into escrow accounts as governed by the Significant Reduction Exemptions (SREs) issued by the Trump administration to eight of Iran’s oil purchasers, will not prove as valuable or liquid.

While some have speculated that allowing the rial to depreciate could have served to minimize a budget deficit given the large proportion of foreign exchange revenues, the overall reduction in oil revenue and the need for new expenditures, such as allocations for the import of basic goods and pharmaceuticals, negates any benefit.

In the same vein, given high interest rates on Iran's debt market during the sanctions era, the government will face difficulties in repaying its deferred debts through the issuance of bonds. Furthermore, the Plan and Budget Organization of Iran is set to issue new debt in 2019-20 close to the IRR 560 trillion ceiling specified in the Sixth Development Program.

With revenue squeezed for the reasons outlined above, Rouhani will be under pressure to reduce spending, especially through the elimination of subsidies. First, the administration could decide to end the allocation of subsidized dollars for the import of essential goods and medication. This may exacerbate inflation, but it is not clear as to whether the subsidies are actually serving to keep consumer prices low, or whether importers and wholesalers are padding their profits. If inflation continues slow in coming months as the rial regains value, there may be a case for reducing the subsidy.

Second, the some economic commentators have proposed eliminating subsidies for fuel in the favor of shopping cards that enable households to get discounted prices for essential foodstuffs. This would replace a subsidy for essential goods importers with a subsidy for consumers. Not only would such an approach protect foreign exchange reserves, it arguably would more effectively support underprivileged groups in the society.

Currently, the Rouhani administration has few options as it seeks to avoid a budget deficit. Yet the political tradeoffs required when devising a budget under sanctions may prove more difficult to manage than the economic challenges.

Photo Credit: IRNA

Iranian Protests And The Working Class

◢ There is growing consensus that the core constituency of the recent wave of protests in Iran is working class youth who feel "forgotten" in the country's economic plan.

◢ The expected post-sanctions windfall has yet to materialize and the Rouhani administration will need to decide whether it will compromise on its austerity-type budgets in order to offer some near-term economic relief.

This article was originally published in Lobelog.

In February of 2017, I wrote about Iran’s “forgotten man,” the member of the working class who seemed invisible in the talk of the country’s post-sanctions recovery:

What has been lost is an appreciation that the “normalization” of relations between Iran and the international community is as much about elevating “normal Iranians” into a global consciousness, as it is about matters of international commercial, financial, and legal integration. While there has been progress in building awareness of Iran’s young and highly educated elite, whose start-ups and entrepreneurial verve play into the inherent coverage biases of the international media, a larger swath of society remains ignored. By a similar token, the rise of the “Iranian consumer” with untapped purchasing power and Western tastes has been much heralded, but the reporting fails to appreciate that Iran’s upper-middle class rests upon a much larger base whose primary economic function is not consumption, but rather production.

With the new wave of protests sweeping Iran, it seems that the country’s forgotten men and women may be mobilizing to ensure their voices are heard in Iran and around the world. There is a growing consensus that the protests are comprised primarily of members of the working class, who are most vulnerable to chronic unemployment and a rises in the cost of living.

The idea that these are working class protests has explanatory power. First, if the protests are indeed a working-class mobilization, then they are less surprising, and can be seen as akin to the regular “bread riots” that took place during Ahmadinejad’s second term, when Iran’s economy suffered its sharpest contractions.

Second, a working class outlook may explain why the political slogans and imagery of the Green Movement have not been deployed by the protestors. The Green Movement was a predominately middle class movement focused on civil rights, which emerged in response to a chosen candidate being fraudulently denied an election victory. Solidarity with lower class voters was limited and economic grievances were not a central focus.

Third, such a demographic composition may explain the support conservative political groups in Iran have given to the protestors, despite the spectacle and soundtrack of anti-state slogans that have marked many of the gatherings. Conservative politicians are being careful not to alienate members of their base, while trying to cast the protests the predictable outcome of Rouhani’s economic policies. Moreover, a working class composition of the protests can explain how exactly Iran witnessed a successful presidential election with historic turnout and a clear victor just six months before mass mobilizations in cities across the country to protest the government. It may be that those turning to protest now feel their voice was not heard in the May elections.

A simple comparative review of upper-middle income countries such as Iran—including Brazil, Mexico, Thailand, and Russia, among others—demonstrates that while protests end with political expressions, they usually begin with economic motivations. That Iran’s working classes are ready to mobilize, and that the mobilization was so quick, makes sense within the context of Iran’s current economic malaise.

It is generally overlooked when discussing Iran’s post-sanctions economy that Rouhani has operated an austerity budget since his election in 2013. Some even describe his policies as “neoliberal.” While an imperfect descriptor, his administration’s economic approach does broadly correspond to the neoliberal “Washington consensus,” which seeks economic reform through trade liberalization, privatization, tax reform, and limited public spending, focus on foreign direct investment, among other policies.

Such an economic approach is in many ways understandable. Rouhani is seeking to correct the populist excesses of the Ahmadinejad administration while also addressing longstanding structural issues in Iran’s economy such as its overextended welfare system, a reliance on state-owned enterprise, and cronyism and corruption. But these are, by dint of difficulty, long-term reform projects, which may not fully cohere until after Rouhani’s tenure has ended. In a way, it is laudable that the administration is applying such an outlook for the benefit of what Homa Katouzian has called a “short-term society.” But the near-term political costs are becoming clear.

Rouhani’s budget is ultimately ill-suited to addressing the economic imperative of job creation, which is urgent and at the heart of popular dissatisfaction. As economist Djavad Salehi-Esfahani has written in response to Rouhani’s most recent budget:

One of the main stated goals of this budget is to create jobs, but it is hard to see how it can do that by slashing the development budget at a time that interest rates are very high (they exceed inflation by 5 percentage points or more). The unemployment rate has been rising in the five years that Rouhani has been in office, mainly because of increased supply pressure, but low demand has been an equal culprit. With unfavorable news about the future of the nuclear deal and the removal of sanctions, thanks to the 180-degree turn in US policy toward Iran, the prospects for a foreign-investment driven recovery are dim. With public patience running low, the debates in the parliament over this budget should be more serious than the usual haggling over the needs of special interests.

Most governments in Rouhani’s position pursue expansionary monetary policy and boost public spending to try to drive investment and economic growth. But Iran faces a series of economic challenges that complicate such a response. For example, the principle economic achievement of the Rouhani administration has been to bring inflation under control. The International Monetary Fund expects inflation to sit below 10% this year, down from 40% in 2013. Controlling inflation is critical to bringing stability to prices in Iran’s basket of goods, where other market forces continue to drive up prices. Any attempt to pump money into Iran’s economy to spur investment risks undermining the success on inflation.

Additionally, in the face of low-growth, central banks commonly lower interest rates to make it cheaper to finance new investment. But Iran’s interest rates are being slowly rolled back from a high of 22% to the present level of 18%. Slow adjustments are necessary due to Iran’s banks being overleveraged. Reducing the interest rate too drastically, especially as inflation remains stubborn, would have two effects. First, savers would see their deposits lose value. This would predominately hurt lower-income savers who have a less diversified range of assets. Members of the middle class still benefit from asset appreciation in still robust categories like real estate, stocks, or even gold. Middle class fortunes have improved somewhat following the nuclear deal for this reason. On the contrary, members of the working class rely on interest-bearing deposits accounts to conserve wealth and are therefore very vulnerable to fluctuations in interest rates. The controversy over the unsustainable interest rates offered by unlicensed savings and loan institutions, which spurred protests in cities across Iran in the summer 2017, is indicative of the vulnerability.

Second, a lower interest rate would threaten the financial wellbeing of many of Iran’s banks, which have long skirted reserve ratios and amassed toxic debt. Any attendant drop in deposits would make it even harder for banks to shore up their reserves, making politically fraught recapitalization by the central bank more likely. In the recent assessment of Parviz Aghili, CEO of Iran’s Middle East Bank, it would cost as much as $200 billion to bring Iran’s $700 billion balance sheet in compliance with Basel III standards, which call for a minimum leverage ratio of 6%. By comparison, Rouhani’s total budget for the next Iranian calendar year is $104 billion.

In the face of limited options, the Rouhani administration believed that post-sanctions trade and investment, made possible by the sanctions relief afforded under the Iran nuclear deal, would enable the country to kick-start growth and investment that supports job creation. But the economic dividend of the nuclear deal has not materialized as anticipated. The majority of business leaders believe that this is primarily due to external factors, namely President Trump’s threats to re-impose sanctions on Iran, rather than Iran’s own challenging business environment. The nuclear deal has been so central to Rouhani’s economic plan, with the nuclear deal and investment deals basically conflated in much of the discourse, that the concern around the future of the nuclear deal has also hit confidence in Rouhani’s economic management at large.

Overall, Rouhani is running an austerity budget because he is between a rock and a hard place. The policies he is adopting are economically sensible and necessary—so much so that the budgets have been passed despite pushback from parliament and other corners of the Iranian power structure as to the approach, neoliberal or not. But the policies are politically costly, testing the patience of a people who feel that the hopes for a better livelihood slipping away as the years pass. As Mohammad Ali Shabani writes, the circumstances in Iran can be described by the concept of the J-curve, which posits that mobilizations occur “when a long period of rising expectations and gratifications is followed by a period during which gratifications … suddenly drop off while expectations … continue to rise.”

We cannot fault Iranians for their rising expectations, for they are a people who know their immense potential. This is especially true of the working classes, who have built Iran’s diversified economy with their labor and the country’s rich culture with their values. As Iran has grown richer and more advanced, the burgeoning middle class has come to represent the future. But the recent experiences of wealthier economies offer a cautionary tale about “forgetting” the working classes, and sacrificing their expectations to protect the gratification of others.

Photo Credit: IKCO

To Break With Austerity, Rouhani Must Deliver on Sovereign Debt Sale

◢ To win foreign investment, Iran's needs to boost development expenditures. But expansionary fiscal policy will require a new source of revenue, as oil sales remain stagnant and tax rises remain politically risky.

◢ A sovereign debt sale, long discussed by Iranian officials, is the fundamental way Iran can find the revenues to self-fund growth. The Rouhani administration must focus on making its bond offering a reality.

One of the remarkable, and yet little discussed, aspects of the Iranian election is that Hassan Rouhani triumphed despite being an austerity candidate. His first term was notable for its frugal budgets and commitment to both slash government handouts and reduce expenditures in an effort to tackle inflation. On one hand, the focus on a more disciplined fiscal and monetary policy meant that Rouhani could point to a successful reduction of inflation from over 40% to around 10% while on the campaign trail. On the other hand, job creation has been stagnant and the average Iranian has seen little improvement in their economic well-being.

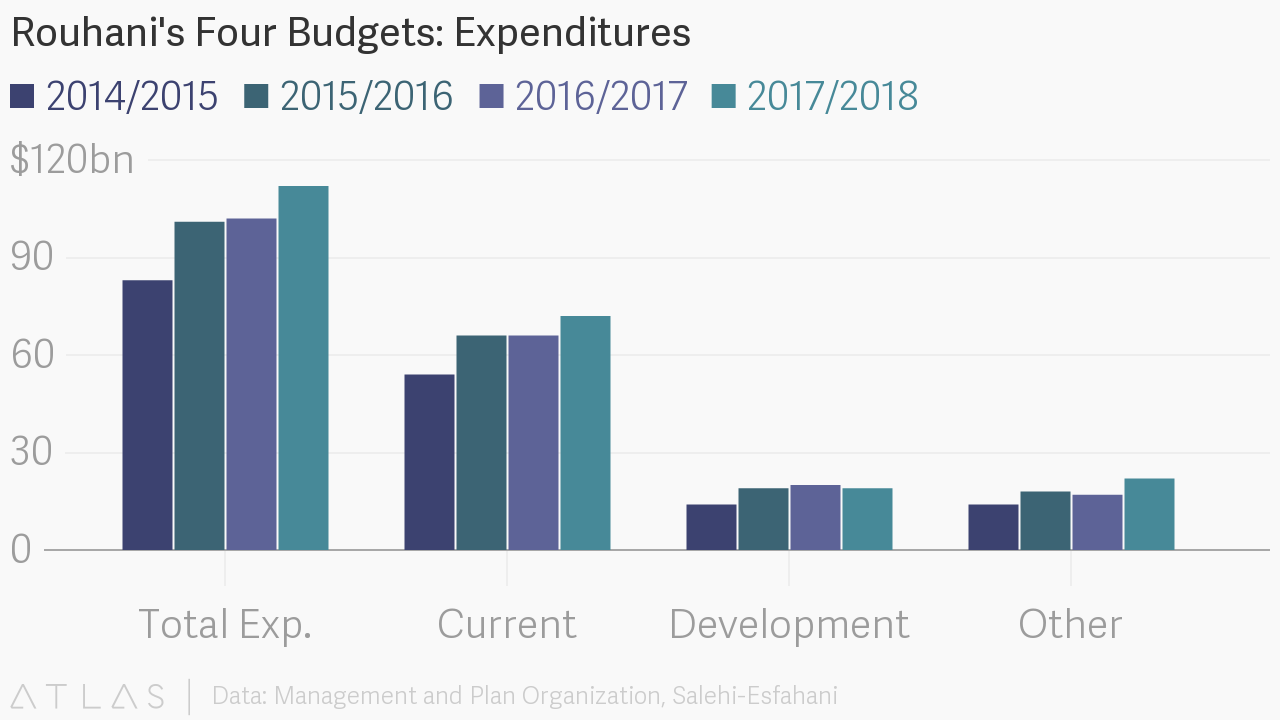

Some economists, including Djavad Salehi-Esfahani, have argued that Rouhani’s austerity economics are misguided, depriving the economy of vital liquidity that could help jumpstart investment and job creation. For example, Iran’s 2017/2018 budget sees tax revenues stay constant at an equivalent of USD 34 billion despite the fact that economic growth is expected to top 6%. Salehi-Esfahani believes that these figures reflect the Rouhani administration's belief “that letting the private sector off easy would encourage it to invest.” The government, meanwhile, will not contribute much more in investment. Development spending is set to decrease from USD 20 billion to USD 19 billion.

Surely, the Rouhani administration’s pursuit of a small government that leaves the burden of job creation and economic growth to the private sector is admirable. It represents a significant shift in the mentality that has characterized the economic policy of the Islamic Republic, which has long relied on state-owned enterprise and state-backed financing, supported by oil revenues, to drive economic growth.

But the volume of investment needed to revitalize economic sectors and create substantial job opportunity has not yet materialized. This is an undeniable fact, which Rouhani has attributed to failures on the part of Western powers to adequately implement sanctions relief, leaving international banks unable to work with Iran. Rouhani’s opponents meanwhile, attributed low volume of foreign direct investment to his administration's mismanagement. There is truth to both accounts.

In many ways, Rouhani’s lean towards austerity was a response to the spendthrift policies of his predecessor, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. The Ahmadinejad administration responded to faltering economic growth during a period of historic oil revenues by ploughing oil rents into the banking system and compelling banks to issue loans. These loans were often provided without the adequate due diligence and were used not to finance growth, but increasingly to fuel speculation, or more forgivably, to address cash flow difficulties faced by companies as a result of international sanctions.

As a result, Iran’s banking sector is now weighed down with a high proportion of non-performing loans, accounting for around 11% of total bank debt. When bank balance sheets grew increasingly precarious as non-payment of loans mounted in the sanctions period, competition for deposits grew. Exacerbating this competition, banks needed to provide higher deposits rates in order to stay ahead of inflation. The combination of forces pushed interest rates up to all-time highs.

The debt market in Iran is now broken. The IMF has urged urgent action to “restructure and recapitalize banks.” In the meantime, banks remain disinclined to lend and in the instances where healthier banks are able to provide loans, borrowers must contend with the high cost of debt.

This may help explain why the Rouhani administration so aggressively sought to address inflation—it was a necessary step to reduce the benchmark interest rate, which has so far been reduced from a high of 22% in 2014 to the current rate of 18%.

But even at such time that interest rates normalize, barriers will remain to the use of debt markets. At a structural level, Iranian companies, particularly in the private sector, rely on equity financing rather than debt financing in order to fund growth. This reflects a “bloc” behavior within Iranian enterprise. Partially as a consequence of the continued dominance of family-owned businesses in Iran’s non-state economy, business leaders tend to approach financiers within their own networks or holding groups, and many of Iran’s largest companies and banks anchor conglomerates that grew out of sequential processes of a kind of inward-looking venture capital. There is limited comfort among Iranian business leaders to seek funding from groups outside of these tight networks and by the same token, equity investors hesitate to provide finance projects outside their own networks. This means that the pool of available investor capital is rarely competing across the whole pool of available capital deployments—a significant inefficiency.

Growth-oriented investing itself can be a difficult strategic proposition. Iranian business leaders have understandably prioritized weathering periods of uncertainty over the execution of long-term plans. The challenge of dealing with short-term volatility has naturally favored short-term thinking. Major companies are only recently undertaking strategic reviews that might identify needs to invest in capital improvements or new services in order to drive growth in support of long-term goals.

The combination of the bloc effect in equity financing and the broken debt market creates a major brake on economic growth, especially from a supply-side perspective. To restore momentum, a third party is needed to order to reset the incentives and mechanisms around financing in Iran.

From the outset of its tenure, the Rouhani administration has hoped foreign investors would take on this role. An influx of foreign investment would have triggered growth without requiring the Rouhani administration to pursue difficult political gambles, such as expanding government expenditure for growth investments in the same period in which welfare programs are being culled. Moreover, the administration’s budgetary leeway was significantly reduced given the persistently low price of oil, making any such balancing act even more fraught.

Eighteen months after Implementation Day, it is clear that the administration significantly overestimated both the attractiveness of the market and underestimated the hesitation of major banks to resume ties with Iran. Investing in Iran is neither easily justified nor easily executed.

The country lacks two essential qualities that have characterized most emerging and frontier markets in the last decade. First, most emerging economies are not as diversified as Iran’s, and do not have such a large arrange of incumbent players with whom any foreign multinational or investor will need to compete for marketshare. There tend to be more “greenfield” opportunities in which lower capital commitment can generate higher returns. Second, a nearly universal feature among emerging markets is the consistent application of both expansionary monetary and fiscal policy. Such policy makes it possible for each investor dollar to achieve a higher return.

In its commitment to reduce interest rates and return the debt markets to normalcy, the Rouhani administration is pursuing an appropriate monetary policy—eventually lenders will become active again. But what remains perplexing is the insistence on austere government budgets in the face of low commitment from foreign investors.

It is clear that the Rouhani administration cannot easily spend tax and oil revenues on long-term projects. Oil revenues are stagnant and there is limited political will to raise taxes. At current levels of government revenue, the political risks of such expenditure are high; as the presidential election showed, populism remains a potent rallying cry among Iranian voters. But foreign investors can’t be expected to step into the gap. Direct equity investments remain a hard sell when domestic financing, whether in equity or debt form, remains throttled and liquidity challenges abound.

There is however a feasible solution that has seen much discussion, but little action—Iran’s return to international debt markets. A sovereign bond issue would both provide Iran’s government the opportunity to raise expenditures in a way that does not draw from existing sources of state revenue by providing a wide class of investors exposure to Iran’s expected period of economic growth. Such a security, ultimately backed by the country’s oil revenues, would serve to mitigate perceptions of country risk for creditors.

In May of 2016, Iran’s finance minister Ali Tayebnia disclosed that discussions were taking place with Moody’s and Fitch over restoring Iran’s sovereign credit rating. One year later, the debt sale continues to be a point of discussion. Recently, Valliolah Seif, Governor of the Central Bank of Iran, commented that the country will issue debt “when [Iran] becomes certain that there is demand for [its] debt.”

Seif’s comments allude to the essential problem of Iran’s planned debt sale—marketing. In order to get Iranian bonds onto the market in any substantial way, the country would need the support of major international banks to serve as underwriters. But banks remain hesitant due to sanctions and political risks.

Turkey, a country which presents creditors significant political risk without mitigation of oil revenues, was able to raise USD $2 billion in a Eurobond sale in January of this year. The sale was underwritten by Barclays, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs and Qatar National Bank.

Iran, is fundamentally a more attractive investment opportunity than Turkey. But major banks remain hesitant to provide financial services to Iran. The Rouhani administration needs to make the sovereign debt sale a core focus of its dialogue with European and global counterparts, and insist on political and technical support in order to entice 2-3 major banks to come on board. In the same manner that the Joint-Commission oversees implementation of the Iran nuclear deal, a multidisciplinary working group needs to be formed to manage the implementation of the debt sale. With the right stakeholders engaged, one can a combination of early-mover banks from Europe, Russia, and Japan agreeing to underwrite the bond issue.

Encouragingly, the delays may have played to Iran’s favor. Emerging markets are just now beginning to rebound, and investors have driven sovereign debt sales to record highs. The Rouhani administration must seize this opportunity and move beyond the limitations of its present austerity economics.

Photo Credit: Wikicommons