Iran's Government Falling into a Debt Trap of Its Own Making

◢ President Rouhani’s budget proposal for the upcoming Iranian year will see the government run a deficit amounting to about 10 percent of GDP or 60 percent of the state’s general budget, excluding oil revenues and withdrawals from the National Development Fund. Rather than increase tax collection to ease budget gaps, the Rouhani administration plans to tap Iran’s nascent debt markets to cover its public spending requirements.

President Rouhani’s budget proposal for the upcoming Iranian year will see the government run a deficit amounting to about 10 percent of GDP or 60 percent of the state’s general budget, excluding oil revenues and withdrawals from the National Development Fund.

Rather than increase tax collection to ease budget gaps, the Rouhani administration plans to tap Iran’s nascent debt markets to cover its public spending requirements. Rouhani’s cabinet intends to issue at least IRR 5 trillion government treasury bills and sukuk bonds in the next Iranian calendar year. For debts already nearing their maturity, it will have to repay close to IRR 3.3 trillion in 2019-20. The recourse to debt markets has economic commentators increasingly concerned over state’s ability to cover rising liabilities in the coming years.

The concern extends to the think tank of the Iranian parliament. Their assessment is that over the next four to five years Iran’s government debt may reach 50-70 percent of GDP, leaving little “fiscal space.” According to the Sixth Development Plan (2016-21), the government is required to keep government debt, including the debt of state-owned enterprises, at below 40 percent of GDP. But it looks likely that the government will exceed this level. Should Iran’s government debt exceed 70 percent of GDP, the fiscal position would be high-risk. Meanwhile, by 2021, interest charges on bonds will constitute 4 percent of GDP, while the total budget deficit is meant to remain below 3 percent of GDP according to parliamentary researchers.

Looking worldwide, high government debt is associated with financial crises. According to data from the OECD, two third of countries hit by the 2009 financial crises were those whose government debt-to-GDP ratio exceeded 60 percent.

When looking to the fraction of the total debt ratio, it is important to consider both the numerator and the denominator. The fact that government bonds in Iran offer 20 percent returns means that interest payments can quickly balloon. Unlike Japan or the United States where interest rates on government bonds are zero percent and 2.4 percent respectively, keeping tabs on fiscal space in Iran requires accounting for the cost of the debt to the government, not merely the amount of debt issued. ‘

Moreover, given that Iran has experienced limited economic growth in recent years and is poised to enter a recession, its fiscal space is expected to decrease. According to the study conducted by The Center for the Management of Debt and Financial Assets of Iran, this proportion was approximately 55.6 percent in 2015.

Putting aside the risks posed by the Rouhani governments turn to debt markets, it is worth asking whether there have been any clear macroeconomic benefits. In the assessment of parliament researchers, the Rouhani administration’s turn to debt markets is only sensible if increased government spending helps generate economic growth.

But with government revenues expected to stagnate, it is unlikely that Rouhani will have sufficient means to encourage the infrastructure projects and other investments to keep Iran’s economic growth at the 2.5 percent level experienced in the first six months of this Iranian year—particularly given the reimposition of US secondary sanctions.

Low or negative growth rates combined with the high interest rates of debt securities mean that the government’s insatiable appetite to underwrite its budget through bond markets may backfire, forcing the Central Bank of Iran to print more money to pay debts, exacerbating the cycle of inflation and devaluation to the detriment of the whole economy. To avoid such an outcome, the Rouhani government must match its turn to debt markets with an effort to expand the tax base.

Photo Credit: IRNA

Europe Can Use Local Currency Bonds to Sustain Economic Ties with Iran

◢ For over a year, European governments have been struggling to determine how they can create a financing facility for projects in Iran. But what if it is a mistake to focus on “external” finance? One underreported effect of Iran’s currency crisis has been the rapid expansion of liquidity in the market. In this environment, a local currency bond offered by a European-owned, Iranian-registered development bank would be highly appealing.

For over a year, European governments have been struggling to determine how they can create a financing facility for projects in Iran. Access to external finance was a major expectation of the sanctions relief promised in return for Iran’s implementation of the JCPOA nuclear deal. With the full return of US sanctions just weeks away, the prospect that Europe will be able to contribute to Iranian economic development through project finance is growing slim.

The European Investment Bank has rejected calls to invest in Iran citing its reliance on global institutional investors, many of them American, to raise capital. A mooted European Monetary Fund, which would source its investment capital from European central banks, is still just a policy idea. Member-state financing vehicles, such as Italy’s Invitalia and France’s Bpifrance have proven unable to engage Iran, despite encouragement from government leaders.

But what if it is a mistake to focus on “external” finance? What if rather than try to source capital from outside of Iran to finance projects within the country, Europe sought to make use of the wealth already within Iran?

One underreported effect of Iran’s currency crisis has been the rapid expansion of liquidity in the market. Iranians are scrambling to convert their devaluing rials into safe-haven assets such as dollar and euro banknotes, gold, property, and even cars. But this scramble, which has seen Iranians draw down their vulnerable rial savings, has led to a rapid expansion in liquidity, which is itself creating inflationary pressure. The Central Bank of Iran is even considering raising interest rates in an effort to reabsorb some of over USD 350 billion floating around the economy.

Perhaps surprisingly, as the currency crisis has unfolded, the Tehran Stock Exchange has hit historic highs. Iranians investors—particularly those whose wealth exceeds that which can be reasonably protected through the purchase of property and gold coins—are increasingly seeing securities and other forms of equity investment as a way to hedge against devaluation. The only problem is that this kind of reinvigorated investment is unlikely to help Iran avoid a recession, particularly in the non-oil sector. Investments on the Tehran Stock Exchange does not lead to the efficient and smart fixed capital formation the country needs to achieve real growth.

The demonstrable hunger for investment opportunities resulting from inflation fears and rising liquidity presents a valuable opportunity. In other emerging markets, such investor demand has been successfully use to source the capital necessary for impactful development projects. The best example can be seen in the financing methods of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

EBRD was established in 1991 to support the liberalization of the Eastern Bloc economies after the fall of the USSR. Just a few years after its launch, EBRD began to tap local investors as a source for its project financing by borrowing and lending in local currencies. EBRD issued its first local currency loan in 1994, denominated in the Hungarian forint. Since then, the bank has issued 722 loans across 26 currencies valued at EUR 12.4 billion.

Local currency financing has been made possible through the issuance of local currency bonds. These bond offerings are issued under local laws and regulations, but are backed by the creditworthiness of ERBD and the steady strength of the Euro. Such “local currency Eurobonds” can be particularly useful to offer domestic investors a hedge against inflation.

In November 2016, EBRD issued a “pioneering” EUR 92 million “inflation-linked Eurobond” in the local currency of Kazakhstan. The bonds have a five-year maturity and “pay a coupon of 3-month Consumer Price Index (CPI) rate plus 10 basis points per annum.” EBRD is also seeking to have the security listed on the Kazakhstan Stock Exchange to make the bond even more accessible to local investors.

When the note was launched, Philip Brown, managing director at Citi Global Markets Limited, which managed the issuance, commented on the “demand for inflation protection from the increasingly sophisticated investor base in Kazakhstan. This trade highlights the useful role the EBRD can play in helping local investors meet their needs and in doing so, develop new markets.” While the likes of Citibank would not be managing such a bond issuance in Iran for obvious reasons, it is easy to see how Iran’s own sophisticated investor class would see a rial Eurobond as an attractive asset to guard against rising inflation.

A local currency bond offering would help Europe and Iran achieve several goals. First, European governments would finally be able to source and deploy the the billions of euros in financing that had been promised to Iran in various credit lines, only to be stymied by the hesitance of European banks to facilitate the underlying transactions in the project finance. Second, it would empower European governments to more directly influence regulatory reform in Iran’s banking and finance sector—a role EBRD has actively and successfully played in the markets in which it has investment since its inception. Third, the new bond would help the Central Bank of Iran reign-in excess liquidity in the market in a manner that is likely to create the greatest long-term value for the economy at large. Fourth, the establishment of a European-Iranian development bank would be a powerful political signal at a time when support for the JCPOA is wavering.

Like European Investment Bank, EBRD is too exposed to the United States in order to pursue projects in Iran itself—the US is a 10 percent shareholder of the bank. In order to pursue local currency financing, European governments would need to establish a new state-owned development bank in order to issue the rial-denominated Eurobonds.

Unlike EBRD and for reasons related to sanctions risks, this should be done through the creation of an Iran-registered financial institution owned by European governments, which would enlist the support of local investment banks and brokerages to bring the bond to market. This European-owned and Iranian-registered development bank would raise capital locally and invest locally, reducing the needs to engage in international transactions that are complicated by the returning sanctions. Conceptually, such an institution would be a kind of inverse of the Hamburg-based EIH Bank, but with a development finance rather than trade finance focus.

The creditworthiness of the new bank would be assured based on a sovereign guarantee for the bank and its liabilities from the European shareholders. The fact that the ownership of the bank will not overlap with its country of operation also limits risk. For similar reasons, no multilateral development bank worldwide has had to resort to its callable capital to date.

The envisaged bank would face several challenges including a lack of robust monetary policy in Iran, a relative lack of transparency within capital markets, and high domestic interest rates which could undercut the attractiveness of the bond offering. It would also need to conduct know-your-customer due diligence above and beyond that conducted by Iran’s own brokerages. But the myriad challenges in Iran are probably no greater than those faced in countries such as Kazakhstan, Georgia, and Ukraine where European financial actors have been able to successfully structure the credit facilities.

Encouragingly, the bond market in Iran has matured considerably over the last few years, and local companies and government agencies have developed capabilities in structuring debt instruments with the help of local investment banks and in compliance with the rules of Islamic finance. In the seven years since Islamic sukuk bonds were first introduced to the market, around USD 4 billion in debt has been issued.

Today, Iran’s leading companies regularly raise financing on the order of USD 100 million through individual bond offerings. A local currency Eurobond, which would be used to finance the transformative projects that had been envisioned for post-sanctions Iran, would easily raise amounts on this order. To bring this idea to fruition, European governments would simply need to combine a proven capacity for financial innovation and the commitments of their central banks, two contributions that cannot be sanctioned by the United States.

Photo Credit: Depositphotos

To Break With Austerity, Rouhani Must Deliver on Sovereign Debt Sale

◢ To win foreign investment, Iran's needs to boost development expenditures. But expansionary fiscal policy will require a new source of revenue, as oil sales remain stagnant and tax rises remain politically risky.

◢ A sovereign debt sale, long discussed by Iranian officials, is the fundamental way Iran can find the revenues to self-fund growth. The Rouhani administration must focus on making its bond offering a reality.

One of the remarkable, and yet little discussed, aspects of the Iranian election is that Hassan Rouhani triumphed despite being an austerity candidate. His first term was notable for its frugal budgets and commitment to both slash government handouts and reduce expenditures in an effort to tackle inflation. On one hand, the focus on a more disciplined fiscal and monetary policy meant that Rouhani could point to a successful reduction of inflation from over 40% to around 10% while on the campaign trail. On the other hand, job creation has been stagnant and the average Iranian has seen little improvement in their economic well-being.

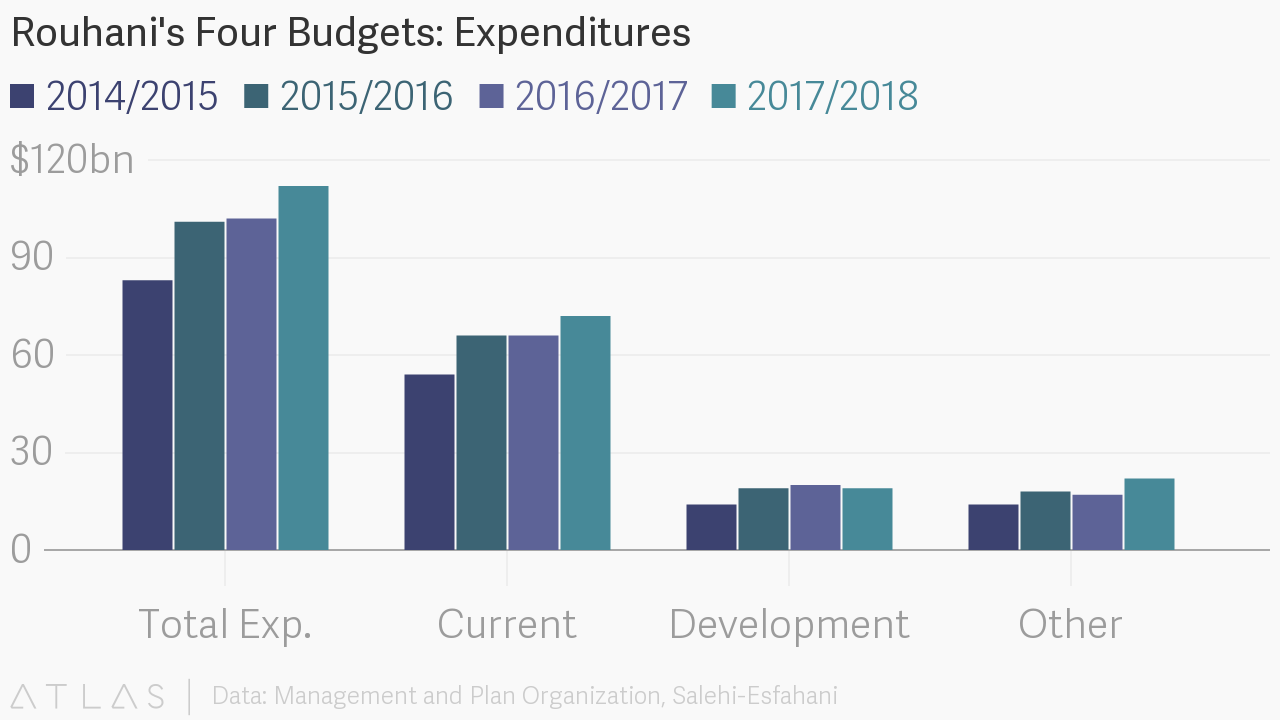

Some economists, including Djavad Salehi-Esfahani, have argued that Rouhani’s austerity economics are misguided, depriving the economy of vital liquidity that could help jumpstart investment and job creation. For example, Iran’s 2017/2018 budget sees tax revenues stay constant at an equivalent of USD 34 billion despite the fact that economic growth is expected to top 6%. Salehi-Esfahani believes that these figures reflect the Rouhani administration's belief “that letting the private sector off easy would encourage it to invest.” The government, meanwhile, will not contribute much more in investment. Development spending is set to decrease from USD 20 billion to USD 19 billion.

Surely, the Rouhani administration’s pursuit of a small government that leaves the burden of job creation and economic growth to the private sector is admirable. It represents a significant shift in the mentality that has characterized the economic policy of the Islamic Republic, which has long relied on state-owned enterprise and state-backed financing, supported by oil revenues, to drive economic growth.

But the volume of investment needed to revitalize economic sectors and create substantial job opportunity has not yet materialized. This is an undeniable fact, which Rouhani has attributed to failures on the part of Western powers to adequately implement sanctions relief, leaving international banks unable to work with Iran. Rouhani’s opponents meanwhile, attributed low volume of foreign direct investment to his administration's mismanagement. There is truth to both accounts.

In many ways, Rouhani’s lean towards austerity was a response to the spendthrift policies of his predecessor, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. The Ahmadinejad administration responded to faltering economic growth during a period of historic oil revenues by ploughing oil rents into the banking system and compelling banks to issue loans. These loans were often provided without the adequate due diligence and were used not to finance growth, but increasingly to fuel speculation, or more forgivably, to address cash flow difficulties faced by companies as a result of international sanctions.

As a result, Iran’s banking sector is now weighed down with a high proportion of non-performing loans, accounting for around 11% of total bank debt. When bank balance sheets grew increasingly precarious as non-payment of loans mounted in the sanctions period, competition for deposits grew. Exacerbating this competition, banks needed to provide higher deposits rates in order to stay ahead of inflation. The combination of forces pushed interest rates up to all-time highs.

The debt market in Iran is now broken. The IMF has urged urgent action to “restructure and recapitalize banks.” In the meantime, banks remain disinclined to lend and in the instances where healthier banks are able to provide loans, borrowers must contend with the high cost of debt.

This may help explain why the Rouhani administration so aggressively sought to address inflation—it was a necessary step to reduce the benchmark interest rate, which has so far been reduced from a high of 22% in 2014 to the current rate of 18%.

But even at such time that interest rates normalize, barriers will remain to the use of debt markets. At a structural level, Iranian companies, particularly in the private sector, rely on equity financing rather than debt financing in order to fund growth. This reflects a “bloc” behavior within Iranian enterprise. Partially as a consequence of the continued dominance of family-owned businesses in Iran’s non-state economy, business leaders tend to approach financiers within their own networks or holding groups, and many of Iran’s largest companies and banks anchor conglomerates that grew out of sequential processes of a kind of inward-looking venture capital. There is limited comfort among Iranian business leaders to seek funding from groups outside of these tight networks and by the same token, equity investors hesitate to provide finance projects outside their own networks. This means that the pool of available investor capital is rarely competing across the whole pool of available capital deployments—a significant inefficiency.

Growth-oriented investing itself can be a difficult strategic proposition. Iranian business leaders have understandably prioritized weathering periods of uncertainty over the execution of long-term plans. The challenge of dealing with short-term volatility has naturally favored short-term thinking. Major companies are only recently undertaking strategic reviews that might identify needs to invest in capital improvements or new services in order to drive growth in support of long-term goals.

The combination of the bloc effect in equity financing and the broken debt market creates a major brake on economic growth, especially from a supply-side perspective. To restore momentum, a third party is needed to order to reset the incentives and mechanisms around financing in Iran.

From the outset of its tenure, the Rouhani administration has hoped foreign investors would take on this role. An influx of foreign investment would have triggered growth without requiring the Rouhani administration to pursue difficult political gambles, such as expanding government expenditure for growth investments in the same period in which welfare programs are being culled. Moreover, the administration’s budgetary leeway was significantly reduced given the persistently low price of oil, making any such balancing act even more fraught.

Eighteen months after Implementation Day, it is clear that the administration significantly overestimated both the attractiveness of the market and underestimated the hesitation of major banks to resume ties with Iran. Investing in Iran is neither easily justified nor easily executed.

The country lacks two essential qualities that have characterized most emerging and frontier markets in the last decade. First, most emerging economies are not as diversified as Iran’s, and do not have such a large arrange of incumbent players with whom any foreign multinational or investor will need to compete for marketshare. There tend to be more “greenfield” opportunities in which lower capital commitment can generate higher returns. Second, a nearly universal feature among emerging markets is the consistent application of both expansionary monetary and fiscal policy. Such policy makes it possible for each investor dollar to achieve a higher return.

In its commitment to reduce interest rates and return the debt markets to normalcy, the Rouhani administration is pursuing an appropriate monetary policy—eventually lenders will become active again. But what remains perplexing is the insistence on austere government budgets in the face of low commitment from foreign investors.

It is clear that the Rouhani administration cannot easily spend tax and oil revenues on long-term projects. Oil revenues are stagnant and there is limited political will to raise taxes. At current levels of government revenue, the political risks of such expenditure are high; as the presidential election showed, populism remains a potent rallying cry among Iranian voters. But foreign investors can’t be expected to step into the gap. Direct equity investments remain a hard sell when domestic financing, whether in equity or debt form, remains throttled and liquidity challenges abound.

There is however a feasible solution that has seen much discussion, but little action—Iran’s return to international debt markets. A sovereign bond issue would both provide Iran’s government the opportunity to raise expenditures in a way that does not draw from existing sources of state revenue by providing a wide class of investors exposure to Iran’s expected period of economic growth. Such a security, ultimately backed by the country’s oil revenues, would serve to mitigate perceptions of country risk for creditors.

In May of 2016, Iran’s finance minister Ali Tayebnia disclosed that discussions were taking place with Moody’s and Fitch over restoring Iran’s sovereign credit rating. One year later, the debt sale continues to be a point of discussion. Recently, Valliolah Seif, Governor of the Central Bank of Iran, commented that the country will issue debt “when [Iran] becomes certain that there is demand for [its] debt.”

Seif’s comments allude to the essential problem of Iran’s planned debt sale—marketing. In order to get Iranian bonds onto the market in any substantial way, the country would need the support of major international banks to serve as underwriters. But banks remain hesitant due to sanctions and political risks.

Turkey, a country which presents creditors significant political risk without mitigation of oil revenues, was able to raise USD $2 billion in a Eurobond sale in January of this year. The sale was underwritten by Barclays, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs and Qatar National Bank.

Iran, is fundamentally a more attractive investment opportunity than Turkey. But major banks remain hesitant to provide financial services to Iran. The Rouhani administration needs to make the sovereign debt sale a core focus of its dialogue with European and global counterparts, and insist on political and technical support in order to entice 2-3 major banks to come on board. In the same manner that the Joint-Commission oversees implementation of the Iran nuclear deal, a multidisciplinary working group needs to be formed to manage the implementation of the debt sale. With the right stakeholders engaged, one can a combination of early-mover banks from Europe, Russia, and Japan agreeing to underwrite the bond issue.

Encouragingly, the delays may have played to Iran’s favor. Emerging markets are just now beginning to rebound, and investors have driven sovereign debt sales to record highs. The Rouhani administration must seize this opportunity and move beyond the limitations of its present austerity economics.

Photo Credit: Wikicommons