The Middle East’s Next Conflicts Won’t Be Between Arab States and Iran

The Arab moment has passed. Competition between non-Arab powers—Turkey, Iran, and Israel—will shape the region’s future.

By Vali Nasr

For more than two decades, the United States has seen the politics of the Middle East as a tug of war between moderation and radicalism—Arabs against Iran. But for the four years of Donald Trump’s presidency, it was blind to different, more profound fissures growing among the region’s three non-Arab powers: Iran, Israel, and Turkey.

For the quarter century after the Suez crisis of 1956, Iran, Israel, and Turkey joined forces to strike a balance against the Arab world with U.S. help. But Arab states have been sliding deeper into paralysis and chaos since the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, followed by the failed Arab Spring, leading to new fault lines. Indeed, the competition most likely to shape the Middle East is no longer between Arab states and Israel or Sunnis and Shiites—but among the three non-Arab rivals.

The emerging competitions for power and influence have become severe enough to disrupt the post-World War I order, when the Ottoman Empire was split into shards that European powers picked up as they sought to control the region. Although fractured and under Europe’s thumb, the Arab world was the political heart of the Middle East. European rule deepened cleavages of ethnicity and sects and shaped rivalries and battle lines that have survived to this day. The colonial experience also animated Arab nationalism, which swept across the region after World War II and placed the Arab world at the heart of U.S. strategy in the Middle East.

All of that is now changing. The Arab moment has passed. It is now the non-Arab powers that are ascendant, and it is the Arabs who are feeling threatened as Iran expands its reach into the region and the United States reduces its commitment. Last year, after Iran was identified as responsible for attacks on tankers and oil installations in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, Abu Dhabi cited the Iranian threat as a reason to forge a historic peace deal with Israel.

But that peace deal is as much a bulwark against Turkey as it is against Iran. Rather than set the region on a new course toward peace, as the Trump administration claimed, the deal signals an intensification of rivalry among Arabs, Iranians, Israelis, and Turks that the previous administration failed to take into consideration. In fact, it could lead to larger and more dangerous regional arms races and wars that the United States neither wants nor can afford to get entangled in. So, it behooves U.S. foreign policy to try to contain rather than stoke this new regional power rivalry.

Iran’s pursuit of a nuclear capability and its use of clients and proxies to influence the Arab world and attack U.S. interests and Israel are now familiar. What is new is Turkey’s emergence as an unpredictable disrupter of stability across a much larger region. No longer envisioning a future in the West, Turkey is now more decidedly embracing its Islamic past, looking past lines and borders drawn a century ago. Its claim to the influence it had in the onetime domains of the Ottoman Empire can no longer be dismissed as rhetoric. Turkish ambition is now a force to be reckoned with.

For example, Turkey now occupies parts of Syria, has influence in Iraq, and is pushing back against Iran’s influence in both Damascus and Baghdad. Turkey has increased military operations against Kurds in Iraq and accused Iran of giving refuge to Turkey’s Kurdish nemesis, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).

Turkey has inserted itself in Libya’s civil war and most recently intervened decisively in the dispute in the Caucasus between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh. Officials in Ankara are also eyeing expanded roles in the Horn of Africa, and in Lebanon, while Arab rulers worry about Turkish support for the Muslim Brotherhood and its claim to have a say in Arab politics.

Each of the three non-Arab states has justified such encroachments as necessary for security, but there are also economic motivations—for example, access to the Iraqi market for Iran or pole positions for Israel and Turkey in harnessing the rich gas fields in the Mediterranean seabed.

Predictably, Turkish expansionism runs up against Iranian regional interests in the Levant and the Caucasus in ways that evoke Turkey’s imperial past. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s recent recitation of a poem lamenting the division of historic Azerbaijan—the southern part of which now lies inside Iran—during a triumphant visit to Baku invited a sharp rebuke from Iran’s leaders. This was not an isolated misstep.

Erdogan has been for some time suggesting that Mustafa Kemal Ataturk was wrong to give up Ottoman Arab territories as far south as Mosul. In reviving Turkish interest in those territories, Erdogan is claiming greater patriotism than that of the founder of modern Turkey and making clear that he is breaking with the Kemalist legacy in asserting Turkish prerogatives in the Middle East.

In the Caucasus, as in Syria, Turkish and Iranian interests are interwoven with those of Russia. The Kremlin’s interest in the Middle East is expanding, not only in conflicts in Libya, Syria, and Nagorno-Karabakh but also on the diplomatic scene from OPEC to Afghanistan. Moscow maintains close ties with all of the region’s key actors, sometimes tilting in favor of one and then the other. It has used this balancing act to expand its advantage. What it wants from the Middle East remains unclear, but with U.S. attention on the wane, Moscow’s complex web of ties is poised to play an outsized role in shaping the region’s future.

Israel, too, has expanded its footprint in the Arab world. In 2019, Trump recognized Israel’s half-century-old claim to the Golan Heights, which it seized from Syria in 1967, and now Israeli leaders are planning out loud to expand their borders by formally annexing parts of the West Bank. But the Abraham Accords suggest that the Arabs are looking past all of that to shore up their own position. They want to compensate for America’s dwindling interest in the Middle East with an alliance with Israel against Iran and Turkey. They see in Israel a crutch to keep them in the great game for regional influence.

The tensions between Iran and Israel have escalated markedly in recent years as Iran has reached farther into the Arab world. The two are now engaged in a war of attrition, in Syria and in cyberspace. Israel has also targeted Iran’s nuclear and missile programs directly and has been blamed most recently for the assassination of Iran’s top nuclear scientist.

But the scramble for the Middle East is not just about Iran. Turkey’s relations with Israel, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Egypt have been deteriorating for a decade. Just as Iran supports Hamas against Israel, Turkey has followed suit but has also angered Arab rulers by supporting the Muslim Brotherhood. Turkey’s current regional posture—extending into Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, and the Horn of Africa while staunchly defending Qatar and the Tripoli government in Libya’s civil war—is in direct conflict with policies pursued by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Egypt.

This all suggests that the driving force in the Middle East is no longer ideology or religion but old-fashioned realpolitik. If Israel boosts the Saudi-Emirati position, those who feel threatened by it, like Qatar or Oman, can be expected to rely on Iran and Turkey for protection. But if the Israeli-Arab alignment will give Iran and Turkey reason to make common cause, Turkey’s aggressive posture in the Caucasus and Iraq could become a worry for Iran. Turkey’s military support for Azerbaijan now aligns with Israel’s support for Baku, and Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE have found themselves in agreement worrying about the implications of Turkey’s successful maneuver in that conflict.

As these overlapping rivalries crisscross the region, competitions are likely to become more unpredictable, as will the pattern of tactical alliances. In turn, that might invite meddling by Russia, which has already proved adept at exploiting the region’s fissures to its advantage. China, too, may follow suit; its talk of strategic partnership with Iran and nuclear deal with Saudi Arabia may well be just the opening act. The United States thinks of China in terms of the Pacific, but the Middle East abuts China’s western frontier, and it is through that gateway that Beijing’s will pursue its vision for a Eurasian zone of influence.

The Biden administration could play a key role in reducing tensions by encouraging regional dialogue and—when possible—use its influence to end conflicts and repair relations. In response to change in Washington, feuding adversaries are signaling a truce, and that provides the new administration with an opportunity.

Although relations with Turkey have frayed, it remains a NATO ally. Washington should focus on improving ties between not just Israel and Turkey but also among Turkey and Saudi Arabia and UAE—and that means pushing Riyadh and Abu Dhabi to truly mend ties with Qatar. The Gulf rivals have declared a truce, but fundamental issues that divided them persist, and unless those are fully resolved, their differences could cause another breach.

Iran is a harder problem. U.S. officials will have to first contend with the future of the nuclear deal, but sooner rather than later Tehran and Washington will have to talk about Iran’s expansionist push in the broader region and its ballistic missiles. Washington should encourage its Arab allies, too, to embrace this approach and also engage Iran. Ultimately reining in Iran’s proxies and limiting its missiles can be achieved through regional arms control and building a regional security architecture. The United States should facilitate and support that process, but regional actors have to embrace it.

The Middle East is at the edge of a precipice, and whether the future is peaceful hinges on what course the United States follows. If the Biden administration wants to avoid endless U.S. engagements in the Middle East, it must counterintuitively invest more time and diplomatic resources in the region now. If Washington wants to do less in the Middle East in the future, it has to first do more to achieve a modicum of stability. It has to start by taking a broader view of regional dynamics and making the lessening of new regional power rivalries its priority.

Vali Nasr is the Majid Khadduri professor of Middle East studies and international affairs at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies. He served in the U.S. State Department from 2009 to 2011.

Photo: IRNA

Full Remarks Made by the Iranian President at the United Nations

◢ The prepared remarks of Iranian President Hassan Rouhani delivered at the United Nations General Assembly on September 25, 2019. They are published here in full in the interest of providing fuller insight into Iran’s intended message on the potential for diplomacy with the United States.

Editor’s Note: The following are the prepared remarks of Iranian President Hassan Rouhani delivered at the United Nations General Assembly on September 25, 2019. The remarks, which have not been checked against delivery, were provided by the Permanent Mission of the Islamic Republic of Iran to the United Nations. They are published here in full in the interest of providing fuller insight into Iran’s intended message on the potential for diplomacy with the United States.

In the name of God, the Most Compassionate, the Most Merciful

Mr. President

I would like to congratulate your deserved election as the president of the seventy-fourth General Assembly of the United Nations and wish success and good luck for Your Excellency and the honorable Secretary General.

At the outset, I should like to commemorate the freedom-seeking movement of Hossein (PBUH) and pay homage to all the freedom-seekers of the world who do not bow to oppression and aggression and tolerate all the hardship of the struggle for rights, as well as to the spirits of all the oppressed martyrs of terrorist strikes and bombardment in Yemen, Syria, Occupied Palestine, Afghanistan and other countries of the world.

Ladies and Gentlemen

The Middle East is burning in the flames of war, bloodshed, aggression, occupation and religious and sectarian fanaticism and extremism; And under such circumstances, the suppressed people of Palestine are the biggest victim. Discrimination, appropriation of lands, settlement expansions and killings continue to be practiced against the Palestinians.

The US and Zionist imposed plans such as the deal of century, recognizing Beit-ul Moqaddas as the capital of the Zionist regime and the accession of the Syrian Golan to other occupied territories are doomed.

As against the US destructive plans, the Islamic Republic of Iran’s regional and international assistance and cooperation on security and counter-terrorism have been so much decisive. The clear example of such an approach is our cooperation with Russia and Turkey within the Astana format on the Syrian crisis and our peace proposal for Yemen in view of our active cooperation with the special envoys of the Secretary General of the United Nations as well as our efforts to facilitate reconciliation talks among the Yemen parties which resulted in the conclusion of the Stockholm peace accord on HodaydaPort.

Distinguished Participants

I hail from a country that has resisted the most merciless economic terrorism, and has defended its right to independence and science and technology development. The US government, while imposing extraterritorial sanctions and threats against other nations, has made a lot of efforts to deprive Iran from the advantages of participating in the global economy, and has resorted to international piracy by misusing the international banking system.

We Iranians have been the pioneer of freedom-seeking movements in the region, while seeking peace and progress for our nation as well as neighbors; and we have never surrendered to foreign aggression and imposition.We cannot believe the invitation to negotiation of people who claim to have applied the harshest sanctions of history against the dignity and prosperity of our nation. How someone can believe that the silent killing of a great nation and pressure on the life of 83 million Iranians arewelcomed by the American government officials who pride themselves on such pressures and exploit sanctionsin an addictive manner against a spectrum of countries such as Iran, Venezuela, Cuba, China and Russia. The Iranian nation will never ever forget and forgive these crimes and criminals.

Ladies and Gentlemen

The attitude of the incumbent US government towards the nuclear deal or the JCPOA not only violates the provisions of the UN Security Council Resolution 2231, but also constitutes a breach of the sovereignty and political and economic independence of all the world countries.

In spite of the American withdrawal from the JCPOA, and for one year, Iran remained fully faithful to all its nuclear commitments in accordance with the JCPOA. Out of respect for the Security Council resolution, we providedEurope with the opportunity to fulfill its 11 commitments made to compensate the US withdrawal. However, unfortunately, we only heard beautiful words while witnessing no effective measure. It has now become clear for all that the United States turns back to its commitments and Europe is unable and incapable of fulfilling its commitments. We even adopted a step-by-step approach in implementing paragraphs 26 and 36 of the JCPOA. And we remain committed to our promises in the deal. However, our patience has a limit; When the US does not respect the United Nations Security Council, and when Europe displays inability, the only way shall be to rely on national dignity, pride and strength. They call us to negotiation while they run away from treaties and deals. We negotiated with the incumbent US government on the 5+1 negotiating table; however, they failed to honor the commitment made by their predecessor.

On behalf of my nation and state, I would like to announce that our response to any negotiation under sanctions is negative. The government and people of Iran have remained steadfast against the harshest sanctions in the past one and a half years ago and will never negotiate with an enemy that seeks to make Iran surrender with the weapon of poverty, pressure and sanction.

If you require a positive answer, and as declared by the leader of the Islamic Revolution, the only way for talks to begin is return to commitments and compliance.

If you are sensitive to the name of the JCPOA, well, then you can return to its framework and abide by the UN Security Council Resolution 2231. Stop the sanctions so as to open the way for the start of negotiations.

I would like to make it crystal clear: If you are satisfied with the minimums, we will also convince ourselves with the minimums; either for you or for us. However, if you require more, you should also pay more.

If you stand on your word that you only have one demandfor Iran i.e. non-production and non-utilization of nuclearweapons, then it could easily be attained in view of the IAEA supervision and more importantly, with the fatwa of the Iranian leader. Instead of show of negotiation, you shall return to the reality of negotiation. Memorial photo is the last station of negotiation not the first one.

We in Iran, despite all the obstructions created by the US government, are keeping on the path of economic and social growth and prosperity. Iran’s economy in 2017, registered the highest economic growth rate in the world. And today, despite fluctuations emanating from foreign interference in the past one and a half years, we have returned to the track of growth and stability. Iran’s gross domestic product minus oil has become positive again in recent months. And the trade balance of the country remains positive.

Distinguished Participants

The security doctrine of the Islamic Republic of Iran is based on the maintenance of peace and stability in the Persian Gulf and providing freedom of navigation and safety of movement in the Strait of Hurmoz. Recentincidents have seriously endangered such security. Security and peace in the Persian Gulf, Sea of Oman and the Strait of Hormuz could be provided with the participation of the countries of the region and the free flow of oil and other energy resources could be guaranteed provided that we consider security as an umbrella in all areas for all the countries.

Upon the historical responsibility of my country in maintaining security, peace, stability and progress in the Persian Gulf region and Strait of Hormuz, I should like to invite all the countries directly affected by the developments in the Persian Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz to the Coalition for Hope meaning Hormuz Peace Endeavor.

The goal of the Coalition for Hope is to promote peace, stability, progress and welfare for all the residents of the Strait of Hormuz region and enhance mutual understanding and peaceful and friendly relations amongst them.

This initiative includes various venues for cooperation such as the collective supply of energy security, freedom of navigation and free transfer of oil and other resources to and from the Strait of Hormuz and beyond.

The Coalition for Hope is based on important principles such as compliance with the goals and principles of the United Nations, mutual respect, equal footing, dialog and understanding, respect to territorial integrity and sovereignty, inviolability of international borders, peaceful settlement of all differences, rejection of threat or resort to force and more importantly two fundamental principles of non-aggression and non-interference in the domestic affairs of each other. The presence of the United Nations seems necessary for the creation of an international umbrella in support of the Coalition for Hope.

The Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Islamic Republic of Iran shall provide more details of the Coalition for Hope to the beneficiary states.

Ladies and Gentlemen

The formation of any security coalition and initiative under any title in the region with the centrality and command of foreign forces is a clear example of interference in the affairs of the region. The securitization of navigation is in contravention of the right to free navigation and the right to development and wouldescalate tension, and more complication of conditions and increase of mistrust in the region while jeopardizing regional peace, security and stability.

The security of the region shall be provided when American troops pull out. Security shall not be supplied with American weapons and intervention. The United States, after 18 years, has failed to reduce acts of terrorism; However, the Islamic Republic of Iran, managed to terminate the scourge of Daesh with the assistance of neighboring nations and governments. The ultimate way towards peace and security in the Middle East passes through inward democracy and outward diplomacy. Security cannot be purchased or supplied by foreign governments.

The peace, security and independence of our neighbors are the peace, security and independence of us. America is not our neighbor. This is the Islamic Republic of Iran which neighbors you and we have been long taught that: Neighbor comes first, then comes the house. In the event of an incident, you and we shall remain alone. We are neighbors with each other and not with the United States.

The United States is located here, not in the Middle East. The United States is not the advocate of any nation; neither is it the guardian of any state. In fact, states do not delegate power of attorney to other states and do not give custodianship to others. If the flames of the fire of Yemen have spread today to Hijaz, the warmonger should be searched and punished; rather than leveling allegations and grudge against the innocence. The security of Saudi Arabia shall be guaranteed with the termination of aggression to Yemen rather than by inviting foreigners. We are ready to spend our national strength and regional credibility and international authority.

The solution for peace in the Arabian Peninsula, security in the Persian Gulf and stability in the Middle East should be sought inside the region rather than outside of it. The issues of the region are bigger and more important than the United States is able to resolve them. The United States has failed to resolve the issue in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria, and has been the supporter of extremism, Talibanism and Daeshism. Such a government is clearly unable to resolve more sophisticated issues.

Distinguished Colleagues

Our region is on the edge of collapse, as a single blunder can fuel a big fire. We shall not tolerate the provocative intervention of foreigners. We shall respond decisively and strongly to any sort of transgression to and violation of our security and territorial integrity. However, the alternative and proper solution for us is to strengthen consolidation among all the nations with common interests in the Persian Gulf and the Hormuz region.

This is the message of the Iranian nation:

Let’s invest on hope towards a better future rather than in war and violence. Let’s return to justice; to peace; to law, commitment and treaty and the negotiating table. Let’s come back to the United Nations.

Photo: IRNA

Iraq's Top Cleric Joins Game of Thrones

◢ Ostensibly, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani’s visit to Iraq was meant to deepen economic ties between the two neighbors, historically divided by political and sectarian enmities as much as they are connected by geography. Only one Iraqi leader could have kept Rouhani at arm’s length: Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, But he didn’t. The audience he gave the Iranian president says as much about Sistani’s own political adventurism as it does about Iraq’s subservience to Iran.

This article was originally published by Bloomberg Opinion.

Ostensibly, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani’s visit to Iraq was meant to deepen economic ties between the two neighbors, historically divided by political and sectarian enmities as much as they are connected by geography. The trip was also meant to demonstrate to the U.S. that Tehran and Baghdad would still do business with each other, despite the Trump administration’s sanctions on Iran.

None of this was especially remarkable: the Islamic Republic’s influence over Iraq has grown exponentially in recent years, underscored by Iran’s control of Shiite militias that have captured much of the state security apparatus and now loom ever larger on the political stage. No Iraqi government, much less one led by Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi, a weak Shia politician, would dare give a representative of the Iranian regime anything less than an effusive welcome.

Only one Iraqi leader could have kept Rouhani at arm’s length: Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, the country’s most revered cleric. But he didn’t. The audience he gave the Iranian president in the Shia holy city of Najaf says as much about Sistani’s own political adventurism as it does about Iraq’s subservience to Iran.

First, a little background. Sistani, now 88, became a Grand Ayatollah—the highest office in the Shia clergy—during the reign of Saddam Hussein. That he survived the dictator, who ordered the assassination of clerics he disliked, is a testament to Sistani’s studious avoidance of politics. His Friday sermons, often delivered by proxies as he himself aged, made little or no reference to the tyrant’s repression of the Shia.

After a U.S.-led coalition toppled Saddam in 2003, Sistani was able to comment more openly about the way the country was being ruled, criticizing first the American administrators and then the Iraqi governments that followed. But when politicians, keenly aware of his sway over tens of millions of potential voters, sought his endorsement, Sistani demurred. The most he would do is express indirect support for a coalition of Shia parties.

That began to change after the 2014 parliamentary election, which resulted in a hung parliament, followed by frenetic behind-the-scenes jockeying for power by the two-term Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki and other Shia contenders. A letter from Sistani, calling for the “selection of a new prime minister who has wide national acceptance,” was interpreted as a thumbs-down for Maliki: he was not new, and, having lost control of large parts of the country to ISIS, did not have wide national acceptance.

Four years later, the beneficiary of Sistani’s intervention, Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi, would himself fall at the Grand Ayatollah’s command. After another indecisive election, Sistani opined that politicians in power should not retain their offices. Although Abadi had only been in charge for one term, during which he had overseen the recapture of territory from ISIS, he was weakened by discontent over corruption and shortages of water and electricity: Sistani’s decree doomed him. (Sistani is apparently untroubled by the public offices that Abdul Mahdi has previously held, including two cabinet posts and the vice presidency, none of them with any distinction.)

Throughout, Sistani remained uninterested in Iraq’s external relations. In 2008, when Mahmoud Ahmadinejad became the first Iranian president to visit postwar Iraq, the Grand Ayatollah turned down requests for an audience. Nor did Sistani meet any American president. He did receive Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in 2011.

So why now—and why Rouhani? Grand Ayatollahs tend not to care about quotidian matters such as economic ties, or sanctions. Nor would Sistani feel threatened by Iran’s proxy militias: his personal prestige is so great, they would not dare move against him.

One explanation: By welcoming Rouhani, a relatively moderate cleric, Sistani is sending a message to Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, a hardliner. That would mark the first time that Sistani has sought to meddle in the politics of a neighboring country—and a traditional enemy, to boot. Doing so is uncharacteristically bold.

To what end, though? Some analysts reckon a blessing from Sistani, who enjoys a wide following in Iran, will strengthen Rouhani’s hand back home. But this is hard to credit: Iranian hardliners have never placed much store by outside clerics, even one so venerable as Sistani. Their power derives from the likes of Khamenei, and looks set to be extended by Ebrahim Raisi, the cleric who runs Iran’s judiciary and will have the greatest say in who succeeds the Supreme Leader.

The other possibility is that Sistani is sending a message to Baghdad—that he is now taking an interest in foreign policy, or at least in Iraqi-Iranian relations. Abdul Mahdi, a reluctant prime minister lacking any political standing, is in no position to object, but many Iraqis will rightly be alarmed. This is especially true of Iraqi Sunnis, many of whom live in fear of the militias backed by the regime Rouhani represents.

The wider Arab world will have noticed that Sistani has never extended the courtesy of an audience to any visiting Arab head of state—whether King Abdullah of Jordan, the Emir of Kuwait, or the presidents of Tunisia, Lebanon and Libya. Dabbling in foreign affairs, the Grand Ayatollah may find, can be a lot trickier than domestic politics.

Photo Credit: IRNA

A New Narrative for Iranian Foreign Policy

◢ What does Zarif's averted resignation mean for Iranian diplomacy? With the erosion of a unipolar world Iran has the chance to shift its foreign policy, whilst continuing to comply with the JCPOA and maintain broad diplomatic engagement.

This article was originally published by IISS.

On Monday, Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammed Javad Zarif announced his resignation in a late-night Instagram post, sending shockwaves through political circles in Iran and abroad. Just ten days earlier, Javad Zarif’s fiery performance at the Munich Security Conference had won him praise across the political spectrum in Iran. At a time when public support for the JCPOA among Iranians has slipped to just 51%, Zarif’s strong message struck a chord with the Iranian public, who flooded social media with clips of him defending Iran’s missile program and refuting any notion that the West held the moral high ground. Zarif also made clear that while Europe has made the ‘right political statements’ regarding the JCPOA, it has yet to prove that it is willing ‘to pay the price’ to defend the deal in the face of US ‘bullying’.

Iranian President Hassan Rouhani has rejected Zarif’s resignation, citing Supreme Leader Ayatollah Sayyid Ali Hosseini Khamenei’s trust in and esteem for Zarif. But the foreign minister’s reasons for tendering his resignation are hardly opaque. With parliamentary and presidential elections on the horizon, and the economy falling under increasing pressure, he has had to reassure the public of the Rouhani administration’s nationalist credentials and parry accusations of weak leadership from hardliners, which tried to impeach him in December 2018 over his support for Iran’s Financial Action Task Force reforms. The last straw was reportedly his exclusion from meetings with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, who was in Tehran on Monday. Zarif felt that the foreign ministry was being unduly sidelined, and told an Iranian newspaper that he sought to defend the ‘integrity’ of the ministry by resigning. Should he stay on, Rouhani and Khamenei’s testimonials may help Zarif prevent the Foreign Ministry’s marginalisation.

Preserving the JCPOA

Regardless of who is foreign minister, Iran’s public diplomacy must find a new balance. Zarif’s resignation illustrates how growing divergence in foreign policy between the Iran’s moderates and hardliners could impede the critical political mission of preserving the JCPOA until 2021, when Iran’s newly elected president will likely have the chance to engage a new American president.

Just as the JCPOA remains the signature foreign policy achievement of the Rouhani administration, it also serves as a symbol of multilateralism for the E3 and especially the European Union. However, as demonstrated by the tortured wording of the recent European Council conclusions on Iran, there is growing fatigue in Europe over efforts to shield the JCPOA from the Trump administration’s attacks and increasing frustration over what are perceived as Iran’s destabilising activities in the Middle East and—in light of attempted political assassinations—in Europe. Many European officials view Iran as intractable and are inclined to take a much harsher stance, albeit short of the Trump administration’s ‘maximum pressure’ campaign.

So far, officials in favour of engagement and incentivisation continue to set the overall tenor of European policy on Iran. But the emerging political dynamics indicate that a tougher line from Iran will probably lead to a tougher line from Europe. Pressure has thus increased on Iran’s moderates to reassure European stakeholders of their firm commitment to constructive engagement while also showing domestic strength by following principles established over the four decades of the Islamic Republic. Achieving these dual aims will require the Iranian government to cast Iran’s continued compliance with the JCPOA as a defining element of Iran’s national vision.

The erosion of a unipolar world order may facilitate this objective. The United States appears to be losing its berth as the primary architect and steward of the global political and economic system. Through a combination of “America First” policies and the abuse of foreign policy tools such as extraterritorial sanctions, the Trump administration has prompted European leaders to question longstanding structural imbalances in the transatlantic relationship, and to call openly for greater political and economic autonomy. Thomas Wright has observed that the Munich Security Conference marked the end of the “transatlantic charade.”

Multipolar Opportunities

Iranian leaders could exploit this development in several ways. Firstly, they could link Iran’s traditional challenge to US primacy with Europe’s developing interest in strategic autonomy. The launch of the INSTEX special purpose vehicle, which seeks to facilitate Europe–Iran trade in the face of US secondary sanctions, is a start. In Munich, citing near-term practical limitations, Zarif characterised INSTEX as insufficient to honour European commitments to save the nuclear deal, echoing a sentiment shared widely in Tehran. He may have missed an opportunity to cast INSTEX as emblematic of an accelerating European push for greater strategic independence.

Secondly, the Rouhani administration might downplay the withdrawal of the United States from the nuclear deal precisely on account of Washington’s diminished leadership. Any Iranian visions of Iran’s centrality to the prospective integration of Eurasia driven by the remaining non-Iranian parties to the JCPOA—Europe, Russia and China – are exaggerated. In fact, there appears to be little momentum behind Iran’s inclusion in emerging political and economic structures, in part due to US sanctions. But Iran can still project general optimism about a stronger political and economic role in the Eurasian geopolitical space on the basis of positive relations with Europe, Russia and China. In this context, the JCPOA could be portrayed not as an agreement imposed by the United States to shackle Iran but rather as an important security and economic pact that could support its normalization in Eurasia.

Finally, Iran can highlight its interest in advancing the establishment of a multipolar world. For two decades Iran’s foreign policy debate has focused on the choice between East and West. Hardliners have argued that Iran should look east, and forge closer ties with Russia and China, which overlook Iran’s human rights failings and remain largely neutral with respect to Iran’s Middle East activities. Moderates have typically argued that Iran must look west and establish closer ties with the United States and Europe, even if this requires a commitment to political reform. This dichotomy may be obsolete, or at least less useful.

Provided Iranian officials can maintain Iran’s broad diplomatic engagement, they could leave the door open to improved dialogue with the United States while placing the onus on American leaders to earn back trust of the remaining parties to the deal. It bodes well that the Democratic National Committee has already adopted a resolution calling upon the US to re-enter the JCPOA.

Photo Credit: IRNA

The United States and Iran are in a Quantum War

◢ It took just under an hour for staff at Israel’s Government Press Office to delete a tweet that suggested that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had finally decided to wage war on Iran. The conflict Iran faces today is neither a hot war nor a cold war. It is a quantum war—a superimposition of two states of conflict. Put another way, depending on when you observe the facts, Iran is both at war and it is not.

It took just under an hour for staff at Israel’s Government Press Office to delete a tweet that suggested that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had finally decided to wage war on Iran. The office replaced that tweet with another one that clarified that Israel merely seeks to join with Arab nations to “combat Iran.” The most striking thing about the whole fiasco was not that the prime minister was agitating for war. It was that the English word in the original translations seemed so precise and unambiguous: war.

There was a kind of refreshing clarity to the translation that has been elusive in Iran policy, particularly as articulated by the Trump administration. Donald Trump has placed sanctions on Iran ostensibly as an alternative to military confrontation, but he still refers to the sanctions program as part of an “economic war.” The administration creates exemptions for humanitarian trade but ensures that they are not operable. Officials declare their unwavering support for the Iranian people, but bar them from entering the United States under the “Muslim Ban.” The U.S. government devises covert programs to sabotage Iran’s defensive capabilities but then leaks their existence to the press.

Fittingly, Netanyahu’s mistranslation fiasco came during a summit that Trump administration officials insisted was “not a trash-Iran conference.” Yet the prime minister himself assured reporters that the meeting was focused on Iran.

At first glance these might just seem like the hallmarks of the Trump administration’s chaotic, incoherent, and hypocritical policymaking. But perhaps these contradictions are the basis of a new kind of warfare. The conflict Iran faces today is neither a hot war nor a cold war. It is a quantum war—a superimposition of two states of conflict. Put another way, depending on when you observe the facts, Iran is both at war and it is not.

Iran has been stuck in a kind of liminal space of international relations for four decades. But the international community and Iran’s domestic political constituencies now face an unprecedent number of internal divisions over the question of Iran’s place in the world.

Whereas Iran once counted on the support of Russia and China and the relative ambivalence of the Arab states to head off a multilateral challenge from the United States and Europe, today, the United States joins the Arab states and Israel to form a nascent coalition against Iran. These anti-Iranian actors seem principally united by a shared perception of Iran’s threat expressed in increasingly ideological terms. Lacking political legitimacy, such a coalition can neither marshal the kind of containment required for a cold war nor credibly engage in a hot war. What is left is quantum war.

In some respects, this is the worst circumstance for Iran. Whereas hot and cold wars tend to unite people in the country under attack, a quantum war is politically more insidious. Some Iranians believe the nuclear deal is still viable and channels of dialogue with Europe still open, so they remain committed to diplomacy. Others focus on airstrikes from Israel and terrorist attacks abetted by Arab governments, and therefore see no alternative to conflict. According to the 2019 worldwide threat assessment from the director of national intelligence, as a result of such dynamics, “regime hardliners will be more emboldened to challenge rival centrists by undermining their domestic reform efforts and pushing a more confrontational posture toward the United States and its allies.” The Iranian public is equally divided. Today half of Iranians support the nuclear deal, while half do not.

In response to such domestic pressures, Iran has once again returned to hedging on matters related to its foreign relations. In the same week that President Hassan Rouhani announced his willingness to negotiate with the United States should it “repent,” Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei declared that when it comes to the United States, “no problem can be solved.”

The quantum war also poses dilemmas for Europe, which finds itself struggling to craft a coherent policy. A recent statement from the foreign affairs council of the European Union inelegantly sought to warn Iran on its role in Syria, its ballistic missile activities, and its role in assassination plots on European soil while also boasting of the extraordinary efforts being made to sustain bilateral trade in the face of U.S. secondary sanctions. The contradictions do not merely exist on paper. Divisions are increasing not just among EU member states but also within foreign ministries about the right pathway on Iran. Depending on whom you ask, Iran is either a possible regional partner or an incorrigible regional proliferator. Of course, disagreement, debate, and compromise are part of effective policymaking. But at the same time, the European response to the quantum war increasingly resembles quantum diplomacy.

When Erwin Schrödinger devised his famous “Schrödinger Cat” thought experiment to describe the phenomenon of superimposed states, he used a term apt for discussions of foreign policy: verschränkung, or “entanglement.” In the context of quantum mechanics, entanglement occurs “when two particles are inextricably linked together no matter their separation from one another.” Moreover, “although these entangled particles are not physically connected, they still are able to share information with each other instantaneously.”

Few concepts could better describe the quantum war between the United States and Iran, separated by space, but linked in time, signaling their intentions with the immediacy of tweets.

Photo Credit: IRNA

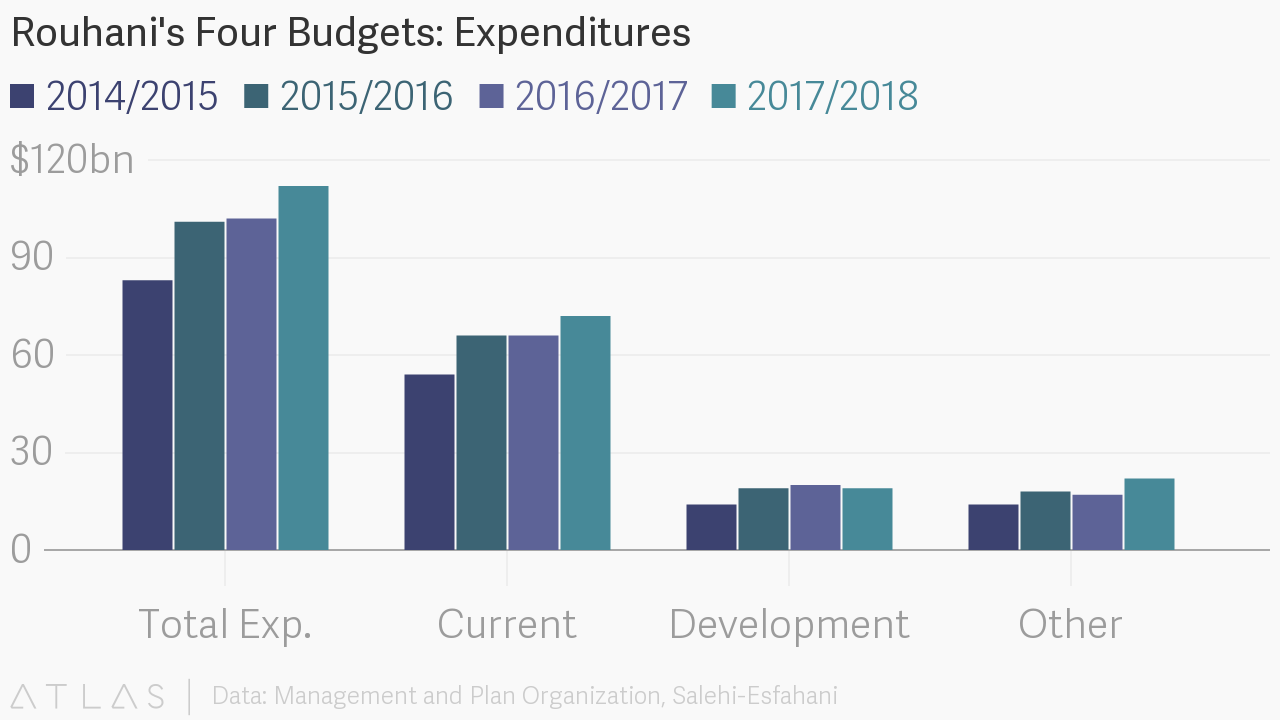

Iran's Government Falling into a Debt Trap of Its Own Making

◢ President Rouhani’s budget proposal for the upcoming Iranian year will see the government run a deficit amounting to about 10 percent of GDP or 60 percent of the state’s general budget, excluding oil revenues and withdrawals from the National Development Fund. Rather than increase tax collection to ease budget gaps, the Rouhani administration plans to tap Iran’s nascent debt markets to cover its public spending requirements.

President Rouhani’s budget proposal for the upcoming Iranian year will see the government run a deficit amounting to about 10 percent of GDP or 60 percent of the state’s general budget, excluding oil revenues and withdrawals from the National Development Fund.

Rather than increase tax collection to ease budget gaps, the Rouhani administration plans to tap Iran’s nascent debt markets to cover its public spending requirements. Rouhani’s cabinet intends to issue at least IRR 5 trillion government treasury bills and sukuk bonds in the next Iranian calendar year. For debts already nearing their maturity, it will have to repay close to IRR 3.3 trillion in 2019-20. The recourse to debt markets has economic commentators increasingly concerned over state’s ability to cover rising liabilities in the coming years.

The concern extends to the think tank of the Iranian parliament. Their assessment is that over the next four to five years Iran’s government debt may reach 50-70 percent of GDP, leaving little “fiscal space.” According to the Sixth Development Plan (2016-21), the government is required to keep government debt, including the debt of state-owned enterprises, at below 40 percent of GDP. But it looks likely that the government will exceed this level. Should Iran’s government debt exceed 70 percent of GDP, the fiscal position would be high-risk. Meanwhile, by 2021, interest charges on bonds will constitute 4 percent of GDP, while the total budget deficit is meant to remain below 3 percent of GDP according to parliamentary researchers.

Looking worldwide, high government debt is associated with financial crises. According to data from the OECD, two third of countries hit by the 2009 financial crises were those whose government debt-to-GDP ratio exceeded 60 percent.

When looking to the fraction of the total debt ratio, it is important to consider both the numerator and the denominator. The fact that government bonds in Iran offer 20 percent returns means that interest payments can quickly balloon. Unlike Japan or the United States where interest rates on government bonds are zero percent and 2.4 percent respectively, keeping tabs on fiscal space in Iran requires accounting for the cost of the debt to the government, not merely the amount of debt issued. ‘

Moreover, given that Iran has experienced limited economic growth in recent years and is poised to enter a recession, its fiscal space is expected to decrease. According to the study conducted by The Center for the Management of Debt and Financial Assets of Iran, this proportion was approximately 55.6 percent in 2015.

Putting aside the risks posed by the Rouhani governments turn to debt markets, it is worth asking whether there have been any clear macroeconomic benefits. In the assessment of parliament researchers, the Rouhani administration’s turn to debt markets is only sensible if increased government spending helps generate economic growth.

But with government revenues expected to stagnate, it is unlikely that Rouhani will have sufficient means to encourage the infrastructure projects and other investments to keep Iran’s economic growth at the 2.5 percent level experienced in the first six months of this Iranian year—particularly given the reimposition of US secondary sanctions.

Low or negative growth rates combined with the high interest rates of debt securities mean that the government’s insatiable appetite to underwrite its budget through bond markets may backfire, forcing the Central Bank of Iran to print more money to pay debts, exacerbating the cycle of inflation and devaluation to the detriment of the whole economy. To avoid such an outcome, the Rouhani government must match its turn to debt markets with an effort to expand the tax base.

Photo Credit: IRNA

Iran Budget Under Scrutiny As Oil Revenues Fall

◢ Next week, President Hassan Rouhani will submit a budget proposal for the forthcoming Persian year (covering March 2019-2020). Currently, the Rouhani administration has few options as it seeks to avoid a budget deficit. Yet the political tradeoffs required when devising a budget under sanctions may prove more difficult to manage than the economic challenges.

Next week, President Hassan Rouhani will submit a budget proposal for the forthcoming Persian year (covering March 2019-2020). The budget bill’s adherence to fiscal rules and the reasonableness of its estimates will be under intense scrutiny given the volatile political and economic climate in Iran.

Policymakers and business leaders see the budget as having four purposes: to maintain economic stability, to boost economic growth, to expand redistribution for poverty reduction, and to supply public goods. Given limited resources related to the reimpositon of sanctions, the Rouhani administration intends to focus on the latter two goals. For example, the administration is slated to earmark USD 14 billion of its hard-earned oil dollars to ease importation of a group of 25 items classified as basic goods and medications.

In the face of such emergency expenditures, the cabinet must carefully balance its budget to ensure that spending is kept in line with revenue, especially given the impact of sanctions on the contribution of oil revenues.

Assuming that Iran will continue to sell 1 million barrels per day (mbpd) of crude oil at USD 54 per barrel, total oil revenues next year will reach approximately USD 20 billion or about IRR 1,140 trillion, at the effective official exchange rate of IRR 57,000. More optimistically, if Iran can manage to keep exports around 1.5 mbpd, the state will earn USD 30 billion, or IRR 1,710 trillion.

According to Iran’s Sixth Development Plan, which establishes guidelines for government budgets and covers a five-year period from 2016, revenue estimates for oil and gas condensate exports cannot exceed a forecasted IRR 1,150 trillion by more than 15 percent. As such, the budget must technically be balanced based on oil revenues of IRR 1,300 trillion. A draft version of the budget places oil revenues at IRR 1,690 trillion, flouting the rule.

Moreover, the Sixth Development Plan mandates that 14.5 percent of oil revenues be allocated to the National Iranian Oil Company, 34 percent to the National Development Fund of Iran (NDFI) and 3 percent for investment in Iran’s underdeveloped regions. The remaining revenues are earmarked for use by the central government.

In an effort to increase its available resources, the Rouhani administration planned to cancel the allocation of oil revenues to NDFI. But Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, intervened to ensure NDFI secures at least a 14 percent allocation. When allocations are reduced, the government typically does not actually transfer the diverted revenue to the Central Bank of Iran, maintaining the funds outside of Iran. This means that the government is effectively printing money, adding inflationary pressure.

A further challenge for the Rouhani government will be that even if oil revenues can be sustained, sanctions will force the government to receive most of its foreign exchange earnings in currencies such as the Indian Rupee, Iraqi Dinar, Turkish Lira and Chinese Yuan. These funds, deposited into escrow accounts as governed by the Significant Reduction Exemptions (SREs) issued by the Trump administration to eight of Iran’s oil purchasers, will not prove as valuable or liquid.

While some have speculated that allowing the rial to depreciate could have served to minimize a budget deficit given the large proportion of foreign exchange revenues, the overall reduction in oil revenue and the need for new expenditures, such as allocations for the import of basic goods and pharmaceuticals, negates any benefit.

In the same vein, given high interest rates on Iran's debt market during the sanctions era, the government will face difficulties in repaying its deferred debts through the issuance of bonds. Furthermore, the Plan and Budget Organization of Iran is set to issue new debt in 2019-20 close to the IRR 560 trillion ceiling specified in the Sixth Development Program.

With revenue squeezed for the reasons outlined above, Rouhani will be under pressure to reduce spending, especially through the elimination of subsidies. First, the administration could decide to end the allocation of subsidized dollars for the import of essential goods and medication. This may exacerbate inflation, but it is not clear as to whether the subsidies are actually serving to keep consumer prices low, or whether importers and wholesalers are padding their profits. If inflation continues slow in coming months as the rial regains value, there may be a case for reducing the subsidy.

Second, the some economic commentators have proposed eliminating subsidies for fuel in the favor of shopping cards that enable households to get discounted prices for essential foodstuffs. This would replace a subsidy for essential goods importers with a subsidy for consumers. Not only would such an approach protect foreign exchange reserves, it arguably would more effectively support underprivileged groups in the society.

Currently, the Rouhani administration has few options as it seeks to avoid a budget deficit. Yet the political tradeoffs required when devising a budget under sanctions may prove more difficult to manage than the economic challenges.

Photo Credit: IRNA

Iran Shows New Savvy in Defining Outcome of Key Nuclear Deal Meeting

◢ Iran has finally learned how to use the Joint Commission of the nuclear deal to tackle its economic challenges. Iranian foreign minister Javad Zarif got what he needed from the ministerial meeting. Two months following Trump’s abrogation of the nuclear deal, the remaining parties to the agreement proved able to present a consensus position on the need to protect Iran’s economic interests in direct contravention of the declared US policy. On practical implementation, bilateral exchanges are the preferred route forward.

Following two months of rising uncertainty after President Trump decided to withdraw from the nuclear deal despite Iran’s continued compliance with its commitments, the remaining parties to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) assembled in Vienna on Friday. The meeting of foreign minister was convened at Iran's request.

Iranian expectations of the meeting centered on an “economic package” that was to be offered by Europe—with the support of Russia and China—to keep Iran in the nuclear deal. As Iranian foreign minister Javad Zarif made clear in a tweet prior to the meeting, in the view of Iran, “sanctions and JCPOA compliance are mutually exclusive.” In short, if Europe, Russia, and China are to expect Iran to remain committed to the nuclear deal, they must neutralize the negative effects of US secondary sanctions.

Up until last week the foremost concern had been whether Iran would be able to maintain viable banking channels in the face of a more aggressive US sanctions posture, especially given the limited progress that had been made in reintegrating Iran into the global financial system since Implementation Day. Yet, the announcement that the US would not be providing significant reduction exceptions to allow Iran’s oil customers to maintain their imports when sanctions return in November, will prove Iran’s most significant challenge. Iran relies on oil exports for 40 percent of government revenue.

Iran engaged in expectation management regarding the package ahead of the meeting, perhaps indicating that the Rouhani government has finally learned the consequences of overselling the economic promises made during JCPOA-related talks. The president’s office released two statements Thursday evening indicating that Rouhani had held phone calls with his German and French counterparts. Most pointedly, Rouhani told Macron that the economic package prepared by Europe "does not include all of [Iran's] demands,” but that Iran remained hopeful that the joint commission meeting would help fill the gaps.

In this way, Friday’s meeting of the joint commission was cast as a test for the French, German, British, Russian, and Chinese diplomats. Would the diplomats be able to develop the necessary economic countermeasures to keep Iran in the deal? Would they be able to show concrete progress on the positive commitments that had been made in the days following Trump’s withdrawal? When drafting the JCPOA, the diplomats had relegated the economic aspects of the deal to an annex, where implementation languished on all sides, slowing trade and investment, until Trump made his fateful decision—was it too much to expect practical solutions to emerge now?

In this context, the joint statement released by the European External Action Service and EU High Representative Federica Mogherini, who chaired the ministerial meeting, was underwhelming. The statement reiterated that “in return for the implementation by Iran of its nuclear-related commitments, the lifting of sanctions, including the economic dividends arising from it, constitutes an essential part of the JCPOA.” As part of this commitment, the statement “affirmed” the commitment of the participants to measures focused on the “promotion of wider economic and sectoral relations with Iran” as well as “the preservation and maintenance of effective financial channels.” Most importantly given Trump’s declared intention to drive Iran’s oil exports to zero, the participants affirmed their intention to defend “Iran’s export of oil and gas condensate, petroleum products and petrochemicals,” among other areas of economic intervention.

The statement was comprehensive in detailing the areas in which Iran wishes to see concrete measures taken, but it did not provide much greater detail than similar statements issued in the weeks immediately following Trump’s withdrawal of the deal. Besides noting that “that the EU is in the process of updating the EU ‘Blocking Statute’" and "the European Investment Bank’s external lending mandate to cover Iran”—two measures first announced in May—no specific tactics were declared in the statement. Of course, it would be a mistake for parties to the JCPOA to reveal their proposed countermeasures too soon, as this would invite American authorities to find ways to undermine them. Yet, nothing in the statement itself seemed to dissuade those hoping for meaningful solutions from a sense of disappointment.

It was therefore notable that Zarif very proactively shared a positive assessment of the meetings upon their conclusion. On one hand, Iran’s foreign minister showed trademark deference to Iran’s other power-brokers, telling reporters that the proposal presented to Iran—“not precise and not a complete one”—should be implemented before the next round of US sanctions come into force in August and that it “is up to the leadership in Tehran to decide whether Iran should remain in the deal” on the basis of this implementation.

Yet, speaking to Iranian media, Zarif highlighted his satisfaction that the parties to the JCPOA, including three “close allies” of the United States, had remained firm in their desire to withstand US pressure. He also highlighted in these interviews and in subsequent tweets that the discussions were “moving in right direction on concrete steps for timely implementation of commitments.” He was remarkably upbeat.

That Iran had achieved a political success was made clear as French foreign minister Jean-Yves Le Drian told reporters that the parties to the deal were trying to deliver an economic package “before sanctions are imposed at the start of August and then the next set of sanctions in November. He added, “ For August it seems a bit short, but we are trying to do it by November.” Le Drian also implored Iran to “stop threatening to break their commitments to the nuclear deal," a statement that may have been taken to undercut the French willingness to help Iran achieve an economic package.

But on the contrary, such as statement proves that Iran retains leverage in the negotiations. Whether signaling the resumption of enrichment activities or the closure of the Strait of Hormuz, a coordinated messaging campaign by the Rouhani administration, which includes public statements by Rouhani himself, by Zarif, by Iran’s atomic energy chief Ali Akbar Salehi, and even by IRGC Quds Force commander Qasem Soleimani, has served to remind the world powers of the significant consequences should Iran withdraw from the deal. The assembled foreign ministers were clear that an economic package is the desired political outcome because they need Iran to remain in the deal. Zarif got what he needed from the ministerial meeting. Two months following Trump’s abrogation of the nuclear deal, the remaining parties to the agreement proved able to present a consensus position on the need to protect Iran’s economic interests in direct contradiction of the declared US policy.

Moreover, while headlines from the likes of Reuters and Bloomberg heralded “no breakthroughs” and “unresolved” issues given the unspecific statement, Zarif’s positive assessment speaks to the fact that Iran was given some indication during the proceedings of what Wall Street Journal reporter Laurence Norman referred to as “real work and genuine ideas” to help Iran both on the banking challenges and the preservation of the all-important oil exports. To this end, Zarif made clear that progress on implementation would follow “direct bilateral efforts.”

It is important to note that the ministerial meeting was far from the only diplomatic or technical dialogue in which Iran has participated since the survival of the nuclear deal was plunged into doubt by Trump’s violation in May. In just the last week, President Rouhani held successful official visits to Switzerland and Austria, two longstanding trading partners. This follows, an important official visit by Rouhani to China, as well as working-level dialogues in France, Sweden, Belgium, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. These meetings have included officials from the Central Bank of Iran, Ministry of Industry, and Ministry of Transportation among executives from state and private sector enterprises. It is these bilateral exchanges, not joint commission dialogues, which have given Iran a more precise indication as to how its economic interests might be protected.

The fact that Iran is back under US secondary sanctions is a failure of multilateralism. But Iran has now recognized that the solution to this failure will not be found in a multilateral format. Whether looking to the European Union or the JCPOA parties, the need to generate politically driven consensus on economic countermeasures will prove cumbersome. As noted by Eldar Mamedov, even the European Parliament is an arena prone to “sabotage." Mamedov, a parliamentarian, illustrates this fact by recounting recent efforts to block the European Investment Bank’s mandate to fund projects in Iran.

A Bourse & Bazaar white paper published in January on the “economic implementation of the nuclear deal” correctly diagnosed that “the joint commission itself is poorly suited to conduct [economic] coordination given the divergent views” of its parties on “matters of sanctions and economic implementation.” In recognition of this fact, the paper recommended that the “European External Action Service (EEAS), which has taken the mantle of leadership on the nuclear deal since the change in American administrations, would be well positioned to convene… a new multi-agency commission for economic implementation, formed in accordance with European commitments under the JCPOA,” In effect, the paper envisioned a joint commission-type body specifically for economic matters. While the joint commission convenes foreign ministers and their diplomatic teams, an economically focused commission would seek to convene economic ministers and their technical staff.

Such a proposal would seem to be supported by the particularly strong stance taken by French economic minister Bruno Le Maire on the need for France to defend its economic interests in Iran in the face of US secondary sanctions. From the Iranian perspective, the inclusion of Laya Joneydi, Iran’s well-regarded vice president for legal affairs, in Iran’s delegation to the joint commission meeting was a positive step, in part because, as noted by Adnan Tabatabai, it was refreshing to see an Iran represented by a female official.

Yet, it is probably the case that convening technocrats into a multilateral format would only serve to limit their effectiveness in the near-term. The political limitations faced by nuclear experts Salehi and US secretary of energy Ernest Moniz during the JCPOA negotiations offers a compelling case study. The Rouhani administration is now aware that given the limited timeframes, Iran’s will need to assemble a patchwork of solutions from various countries, particularly by expanding focus beyond France, Germany and the United Kingdom to seek direct cooperation with a wider ranger of EU member states. Based on institutional and economic factors, some countries will be better able to devise solutions on oil imports, others on banking channels, and others on insulating their multinational corporations or promoting their SMEs. To underscore the point, even the revival of the blocking regulation, a piece of EU law, will depend on the individual implementation and enforcement of member states. When it comes to technical matters and economic implementation, only bilateral dialogues can really deliver.

But if Rouhani and Zarif have learned the limitations of the joint commission and how to work within those limitations, they must also recognize their own limitations. It is impractical for the majority of outreach on the economic package to depend on Zarif and Iran’s foreign ministry. While the lion-like Bijan Zanganeh ably leads the oil ministry, there is a glaring lack of leadership in key bodies such as Iran’s central bank, ministry of economic affairs, and ministry of industry. Both Rouhani and his first vice president Ehsaq Jahangiri have been signaling for several months that a cabinet reshuffle may be on the cards. The politicking behind such a reshuffle is complicated, as parliament would need to confirm new ministers, opening Rouhani to a new round of attacks. But the urgency of new leadership could not be clearer.

If Iran is to succeed in “direct bilateral efforts” to ensure the implementation of an economic package, it must be able to send capable ministers to Europe, Russia, China, and other trading partners to meet with their counterparts in these critical coming months. Zarif can certainly craft a conducive political environment, as evidenced by the positive joint commission outcome, but the foreign ministry cannot orchestrate the defense of Iran’s economy singlehandedly, if for no other reason than the fact that when it comes to the economy, internal challenges greatly outnumber the external ones which Iran's diplomats can reasonable consider within their domain.

Iran demonstrated real savvy in defining the outcome of the joint commission meeting. No longer seeking to unsatisfactorily bend political commitments into practical solutions for its longstanding economic problems, the Iranian delegation proved willing to aptly designate matters of implementation to the numerous bilateral dialogues currently underway. This allowed a relatively positive political outcome to be taken on its own terms, especially with an Iranian audience in mind. If the Rouhani administration can assemble the right teams for these bilateral exchanges, the vital economic package can still be delivered upon. Hope persists.

Photo Credit: EEAS

Europe’s Balancing Act on the Nuclear Deal: Wooing Trump Without Losing Iran

◢ European leaders have been assiduous in lobbying Washington on the nuclear deal. But Europe must step up its diplomacy to ensure it does not lose Tehran in the process and should further make a strong case to the Iranian government and public as to why the nuclear deal can continue to serve Iran’s security and economic interest even without the US.

This piece was originally published on the website of the European Council on Foreign Relations.

For much of Iran’s political elite, and its overwhelmingly young population, the nuclear deal is becoming a story of failure. This situation risks impacting on Tehran’s willingness to engage politically and to reach diplomatic compromises with Western powers. Last week European leaders were in Washington for a last push to keep the United States on board ahead of the 12 May deadline for Donald Trump to issue waivers required under the nuclear deal. During his visit, Emmanuel Macron suggested that the US and Europe could work on a “new deal” with Iran – one which preserves but expands on the 2015 accord. But with Iran kept out of the European-US talks, Hassan Rouhani has questioned the legitimacy of proposals now put forward by Macron and Angela Merkel for Iran to negotiate further deals on its nuclear programme and regional issues. In the process of wooing Washington on this bigger and better deal, Europe must ensure it does not end up losing Tehran, whose buy-in will be essential to succeeding in this effort.

Iran's Rethink on Europe

Despite increasing pressures coming from Trump, Iran has continued to fulfil its part of the deal, as verified by the International Atomic Energy Agency 11 times since the deal was implemented in January 2016. Iran has waited to see what actions Trump would take and carefully assessed the ability and willingness of Europe to safeguard the nuclear deal. In October, Tehran sent out clear signals that it would consider sticking to the deal so long as Europe, China, and Russia could deliver a package that served Iran’s national security interests. But as talks between the US and the EU3 (Germany, France, and the United Kingdom) have stepped up over the last few months, Iranian thinking on European positioning has begun to sour.

Officials and experts from Iran, interviewed on condition of anonymity over the past month, outlined a growing perception inside Tehran that Europe is unable and/or unwilling to deliver on the nuclear agreement without the US. Even those who defend the nuclear deal inside the country are finding it difficult to continue to do so, not just because of Trump but also because of European tactics, which one Iranian official described as “appeasement by Europe to reward the violator of the deal and Iran’s expense”.

This perception has contributed to considerably hardened Iranian rhetoric in recent weeks around a possible US withdrawal. The secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council (SNSC), which includes the most important decision-makers inside the country, warned that Iran may not only walk away from the nuclear deal, but also withdraw from the Non-Proliferation Treaty. Such public statements from senior figures signal that a rethink may be taking place over Iran’s foreign policy orientation and openness to engaging with the West. Decision-makers in Europe should be alert to the gravity of such political shifts.

Keeping Iran on Board

Iranian officials have repeatedly outlined that Iran will abide by the nuclear deal so long as the US does not violate the agreement. If Europe wants to keep Iran on board with the agreement in the scenario where Trump does not issue the sanctions waivers required, or to even sell a new European-US framework to Iran, it will need to shore up its fast-diminishing political capital with Tehran. While Macron’s hour-long call with Rouhani on Sunday was a good start, greater activity is urgently needed.

First, Europeans should seek to alleviate growing Iranian fears that the price of saving the deal will be a wider “pressure package”, one which returns their relations to the pre-2013 policy of isolation and sanctions. While the focus is understandably now on securing ongoing US support for the deal, the EU3 should not neglect the fact that any new framework agreed will require at least some Iranian buy-in to make it workable. In the current political climate in Iran, this is not a given.

As such, the EU3 should, as a unified coalition, work at the highest level with Iran’s foreign ministry to shore up confidence regarding the nuclear deal. In advance of the 12 May deadline, if it looks increasingly likely that Trump will not waive sanctions, the newly appointed German foreign minister should follow up on Macron’s call to Rouhani with a visit to Tehran to meet with their Iranian counterpart and consider contingencies (some measures for which are outlined below).

Second, EU member states should delay the prospect of new sanctions targeting Iranian regional behaviour, at least until firmer guarantees are in place regarding Trump’s decision on the nuclear deal. The timing of such sanctions has reportedly been the topic of heated debate among the 28 member states. At a minimum, the countries supporting such measures should step up their public messaging to communicate the reasons and the targeted nature of new sanctions, including a commitment that these are not the start of more far-reaching sanctions that will hurt the wider Iranian economy. This is particularly the case with Iran’s private sector, which constantly meets new hurdles placed in its way when seeking to do business with Europe.

Third, European governments should double down on efforts to maintain Iranian compliance to the nuclear deal if Trump fails to renew waivers due on 12 May. Such action by the White House would result in the snap-back of US secondary sanctions and are likely to be viewed in Tehran as significant non-performance of the nuclear deal. Europe will need to coordinate with Russia and China to persuade Iran to continue adhering to its nuclear obligations, at least for a period of time. The exhaustion of the dispute resolution mechanism under the nuclear deal can buy time (estimated to be between 2-3 months) for contingency planning while allowing Iran to save face.

In this scenario, European governments will need to convince the US that it will be in their mutual interest to agree on an amicable separation on the nuclear deal. Europeans will need to argue that such a settlement would allow Trump to claim victory with his base for withdrawing US participation in the JCPOA, while avoiding deeper damage to transatlantic relations and possibly maintaining Europe’s quiet compliance on regional issues. This path should also allow the US to reverse its course (Europeans should continue to encourage such a reversal, whatever the 12 May decision).

As part of this contingency plan, to keep Iran on board Europeans will need to offer some degree of economic relief. It will be critical to reach a pan-European deal with the Trump administration to limit the extent to which the US secondary sanctions that may snap back are actually enforced by US regulators. This should include a series of exemptions and carve-outs for European companies already involved in strategic areas of trade and investment with Iran, with the priority being to limit the immediate shock to Iranian oil exports.

European governments should further make a strong case to the Iranian government and public as to why the nuclear deal can continue to serve Iran’s security and economic interest even without the US. They should emphasize the immediate economic benefits of continued oil exports to Europe and possible longer-term commitments for investments in the country. Sustained political rapprochement between Europe and Iran could also influence Asian countries that closely watch European actions (such as Japan, South Korea, and India) to retain economic ties with Iran.

Finally, regardless of the fate of the nuclear deal, Europe should keep the pathway open for regional talks with Iran. Germany, France, the UK, and Italy should establish and formalize a regular high-level regional dialogue with Iran that builds on those held in February in Munich. It is a positive sign that a second round of such talks is reportedly due to be held this month in Rome. Such engagement will become even more important if the US withdraws from the nuclear deal, increasing the risk of regional military escalation that is already surfacing between Israel and Iran in Syria. Europeans should focus these talks on damage limitation and de-escalation in both Yemen and Syria, to help create an Israeli-Iranian and Saudi-Iranian modus vivendi in both conflict theaters (something which the US seems uninterested in).

Ultimately, Iran’s willingness to implement any follow-up measures on regional issues will be heavily influenced by the fate of the nuclear deal and how the fallout over Trump’s actions is managed. Europe may well not be capable of salvaging the deal if the US withdraws from or violates it. But Europe must at least attempt to do so and demonstrate its political willingness through actions that serve as a precedent for the international community. To do otherwise is likely to have an immediate and consequential impact on Iranian foreign policy and significantly reduce Europe’s relevance for the Iranian political establishment. For Iran’s youth, as the largest population bloc in the country, this will be an important experience in how far Europe is willing to go in delivering on its promises to defend the nuclear deal, whose collapse would affect the Iranian psyche and domestic political discourse for years to come.

Photo Credit: Wikicommons

Iran Starved of Investor Capital Needed to Fuel Extensive Privatizations

◢ Morteza Lotfi, the newly appointed head of SHASTA has recently announced a new effort for SHASTA to divest from a large portion of its portfolio, offering a second chance at the privatizations pursued a decade ago.

◢ But political barriers and a dearth of capital, particularly from foreign investors, risks rendering SHASTA's plan dead on arrival as Iran seeks to liberalize without crucial liquidity.

Iran’s long but troubled drive for privatization received a boost earlier this month. Morteza Lotfi, the recently appointed head of Iran’s Social Securities Investment Company (SHASTA), the country’s largest pension provider, announced that SHASTA would list the remaining 25% of its subsidiary companies not currently on the Tehran Stock Exchange. The move was intended to make the companies “more competitive and their financial status more transparent.”

A few weeks later, Lofti made a further announcement that SHASTA plans to sell its stake in 130 companies in a two stage process. An initial tranche of 40 companies has reportedly been prepared for this divestment. Taken together, the two announcements suggest a renewed push for privatization, taking enterprises out of the limbo of SHASTA’s quasi-state ownership in which they have largely languished.

While the market value of the proposed privatization was not given, SHASTA is known to have around 200 subsidiary companies and its holdings are cumulatively valued at USD 9 billion. On this basis, the 130 companies poised for sale could therefore have an estimated value of around USD 5.5 billion, with the caveat that the companies to be offloaded are likely the underperforming firms, with lower valuations than the portfolio average. Nonetheless, in terms of the number of companies and their likely market value, SHASTA’s move would be another historic step in Iran’s economic liberalization.