Iran's Presidential Election Combines Low Turnout with High Stakes

Iran’s two presidential candidates have presented two diverging visions for the future of the Islamic Republic at a time when most Iranians have come to question the fundamental tenets of their political system.

The second round of Iran’s snap presidential election marks a critical moment for the country. On July 5, voters will decide between former deputy head of parliament Masoud Pezeshkian and ex-nuclear negotiator Saeed Jalili. While both candidates will struggle to restore power and prestige to the office of the president, the outcome of the election will be highly consequential for Iran, especially as the succession of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei looms. Pezeshkian and Jalili have presented two diverging visions for the future of the Islamic Republic at a time when most Iranians have come to question the fundamental tenets of their political system.

The political divisions in Iran now extend beyond the long-running rivalry between “Principalists” and “Reformists.” Cleavages exist within progressive and conservative groups and between those who believe in the continuation of the Islamic Republic and those seeking fundamental political change. The record-low turnout in the election’s first round—just 40 percent of eligible voters cast ballots—reflects how a focus on ideological policies has alienated the electorate. In 2021, 18 million people voted for Ebrahim Raisi, whose shock death in a helicopter accident triggered new elections. On June 28, the combined vote for Jalili and third-place contender Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, the leading conservative candidates, totaled less than 13 million.

Reformists have likewise struggled to mobilize voters. Progressive Iranians want action on a wide ranging of issues, including women’s rights, internet censorship, political freedoms, minority rights, foreign relations, jobs and wages, healthcare, climate change, and education. While Pezeshkian, who received 10.4 million votes in the first round, has acknowledged these demands, most progressive voters do not believe he can foster change, and have so far stayed away from the polls.

Moreover, many Iranians opted not to vote because of a widespread belief that the election is illegitimate, owing to perceived election engineering and vote tampering. Many influential political figures have boycotted the snap elections, labelling the process an “election circus.” The sham election that brought Raisi to power in 2021 underscored the regime’s commitment to its own dogma, sacrificing decades of legitimacy earned through elections that were not free, but were competitive.

Raisi was a weak president, presiding over a system in which the executive’s powers are curtailed. Unelected bodies and interests groups enjoy significant influence over government policy in Iran and the Supreme Leader sets the red lines. Voters are under no illusions about the limits of the Iranian president’s power. But within the bounds of Iran’s political system, the divergence in the domestic and foreign policies of different presidents are often stark.

During the debates earlier this week, Pezeshkian and Jalili showcased their contrasting visions. Jalili comes from a self-proclaimed shadow government. He has led from the shadows for eleven years since securing just 4.17 million votes in the 2013 presidential election, which was won by Hassan Rouhani. Jalili champions a future where Iran is detached from Western influence. He vehemently opposes any engagement with the United States and, to a lesser extent, European countries. As a member of the Supreme National Security Council, Jalili used his political power to stymie revival of the Iran nuclear deal. Many fear that, if elected, Jalili might withdraw from the Non-Proliferation Treaty, thrusting Iran back into a nuclear crisis.

On the domestic front, Jalili’s camp includes ultra-conservatives vying for strict Islamic governance, more censorship, and tighter hijab laws and social restrictions. Even though Jalili has positioned himself as a kind of status-quo candidate, poised to maintain the policies of the Raisi administration, he is a divisive figure even within conservative circles. Some Raisi and Ghalibaf allies have indicated that they will support Pezeshkian over Jalili.

That Pezeshkian appeals to some conservatives points to the challenge he faces in mobilizing disaffected voters. His background distinguishes him from recent presidential candidates. He is an accomplished cardiac surgeon with certificates from the United States and Switzerland and served as Mohammad Khatami’s health minister. Some voters have connected with his personal story. Pezeshkian lost his wife and son in a car crash in 1993. He has not remarried.

Pezeshkian has said his foreign policy will be based on “engagement with the world,” which includes “negotiations for lifting sanctions.” Pezeshkian may be permitted to revive talks over the Iran nuclear deal—there is growing awareness among policymakers across Iran’s political specturm that sanctions relief is necessary for getting the economy back on track. However, he will face significant challenges in advancing his domestic policies. The parliament is dominated by hardliners, who will make it difficult for Pezeskhian to confirm his preferred ministers, which may include his outspoken campaign surrogates, former foreign minister Mohammad Javad Zarif and former communications minister Mohammad-Javad Azari Jahromi. Without an intervention from the Supreme Leader to encourage post-election unity, the political paralysis in Iran could prove even worse than in the final years of the Rouhani administration.

The specter of further political paralysis has no doubt deterred voters from believing in the viability of a Pezeshkian presidency. Boycotting the first round allowed the Iranian electorate to send a strong political signal that they will not allow their votes to legitimize a political system that is failing them.

But the stakes seem different now. A Pezeshkian victory appears a real possibility. If 10.4 million had not voted for Pezeshkian in the first round, it would have been reasonable for disaffected voters to completely boycott the election. But on the eve of the final round, voters may be thinking more tactically about the stakes of this election. A Pezeshkian presidency is a chance to hit the brakes at a time when Iran is accelerating towards a deeper political, economic, and social crisis. Whether Pezeshkian can turn the car around remains to be seen. But preventing Jalili from driving the country off a cliff might be reason enough to vote.

Photo: IRNA

Iran's Special Relationship with China Beset by 'Special Issues'

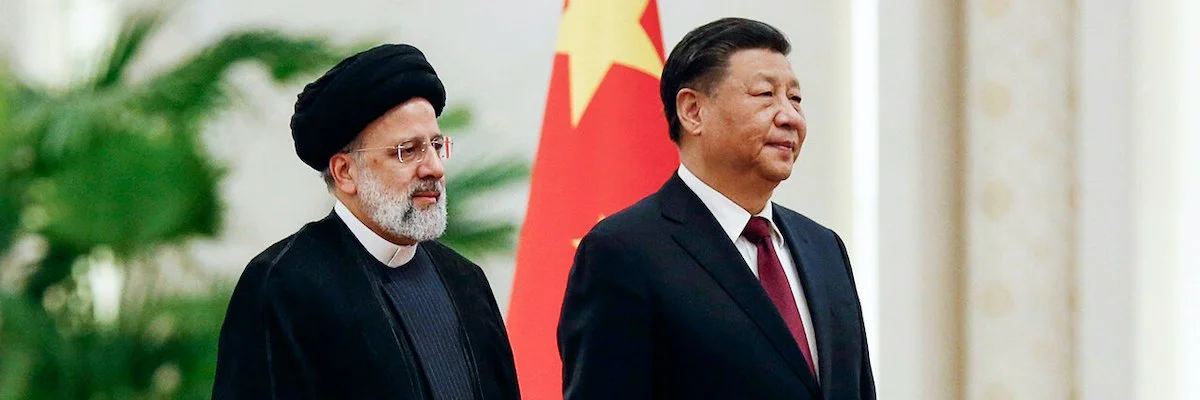

This week, Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi flew to China for a three-day state visit at the invitation of Xi Jinping, marking the first full state visit by an Iranian president in two decades.

On February 14, Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi flew to China for a three-day state visit at the invitation of Xi Jinping, marking the first full state visit by an Iranian president in two decades. For Beijing, hosting Raisi was an attempt to regain Tehran’s trust after the significant controversy generated by the China-GCC joint statement issued following Xi’s visit to Riyadh in December. For Tehran, taking a large delegation to Beijing was an opportunity to remind the world that China and Iran enjoy a special relationship.

On the eve of the visit, Iran, a government newspaper, published a 120-page special issue of its economic insert entirely focused on China-Iran relations. Given the newspaper’s affiliation and the timing of the publication, the special issue is something like a white paper on the Raisi administration’s China policy and the perceived importance of a functional partnership with China.

The cover of the special issue speaks for itself—it calls for the creation of a triangular trade relationship between Iran, China, and Russia. Another headline declares that the Raisi administration is “reconstructing broken Iran-China ties.” In his pre-departure remarks, Raisi doubled down on this message, noting that Iran “has to pursue compensation for the dysfunction that existed up until now in its relations with China.” With this statement, Raisi both cast blame on Hassan Rouhani, his predecessor, for failing to maintain stronger ties with China, while also implying that China had let Iran down by failing to begin implementation of a 25-year Comprehensive Strategic Partnership agreement signed in 2021.

Iran’s grievances aside, the overall tone of the special issue is laudatory, suggesting that the Raisi administration has chosen to overlook China’s apparent endorsement of the UAE’s claim over the three contested Persian Gulf islands, which caused an uproar in Iran following the China-GCC consultations in December. But a development just before Raisi’s trip generated new controversy.

According to reports, Chinese oil major Sinopec has withdrawn from investing in the significant Yadavaran oil field located on the Iran-Iraq border. The Iranian government began negotiating with Sinopec in 2019 to develop the project's second phase. The negotiations were slow-going, in part because of the challenges created by US secondary sanctions.

Fereydoun Kurd Zanganeh, a senior official at the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC), has denied the reports, claiming that negotiations with Sinpoec are ongoing. According to him, the Chinese energy company “has not yet announced in any way that it will not cooperate in the development of the Yadavaran field.” Whether or not Sinopec has actually withdrawn from Yadavaran, the slow pace of the negotiations and the difficulty for Chinese companies to deliver major projects—as in the case of Phase 11 of the South Pars gas field—reflect that China is an unreliable partner for Iran, at least while Iran remains under sanctions.

Nonetheless, the Raisi administration is keen to attract more Chinese investment. In an interview with ISNA published on January 28, Ali Fekri, a deputy economy minister, said that he “is not happy with the volume of the Chinese investment in Iran, as they have much greater capacity.” According Fekri, since the Raisi administration took office, the Chinese have invested $185 million in 25 projects, comprising of “21 industrial projects, two mining projects, one service project, and one agricultural project.” As indicated by the low dollar value relative to the number of investments, Chinese commitments have been limited to small and medium-sized projects. Beijing has mainly invested in projects that, according to Fekri, offer China the opportunity to import goods from Iran.

Comparative data shows Iran falling behind other countries in the race to attract Chinese investment. For instance, according to the data complied by the American Enterprise Institute, China committed $610 million in Iraq and a striking $5.5 billion in Saudi Arabia in 2022 alone. With secondary sanctions in place, the prospect of more Chinese investments in Iran is unrealistic.

Despite these obvious challenges, Iranian officials have been reluctant to admit that external factors are shaping China-Iran relations. Ahead of Raisi’s departure to China, Alireza Peyman Pak, the head of the Iran Trade Promotion Organization (ITPO), denied that Xi Jinping’s visit to Saudi Arabia in December had precipitated a cooling of Beijing’s relations with Tehran.

“Such an interpretation is by no means correct. A country with an economy of $6 trillion naturally tries to develop its economy by working with all countries,” he said. Peyman Pak pointed to recent trade data to bolster his case. “In the past ten months, we have seen a 10 percent growth in exports to China compared to the same period last year,” he added, leaving out that the growth comes from a low base—China-Iran trade has languished since 2018.

In recent months, Peyman Pak has played a prominent role in brokering memorandums of understanding between Russian and Iranian companies—part of the push for a deeper Russia-Iran economic partnership. His participation in the delegation heading to China suggests that the Raisi administration is serious about shaping a triangular trade alliance between Tehran, Moscow, and Beijing. So far, that economic alliance exists only in the form of various non-binding agreements. China and Iran signed 20 agreements worth $10 billion during Raisi’s visit.

These agreements, like those before them, have a low chance of being implemented, especially while the future of the JCPOA remains in doubt. For now, China-Iran relations are limited to the text of white papers, memorandums, and statements. For his part, Xi offered Raisi some encouraging words. He reiterated China’s opposition to “external forces interfering in Iran’s internal affairs and undermining Iran’s security and stability” and promised to work with Iran on “issues involving each other’s core interests.” No doubt, the special relationship between China and Iran is beset by special issues.

Photo: IRNA

Iranian Women are Colliding with the Iranian State

Iranian women, supported by the many men who have now joined them, are challenging the discrimination they have experienced for decades.

On the day that Ebrahim Raisi, Iran’s President, was giving a speech at the United Nations headquarters in New York about the double standards with which human rights are pursued around the world, a tear gas canister flew past me and hit a car that was parked a few metres away. I was among the protesters running down Palestine Street in the centre of Tehran, and the tear gas was being fired directly at us by anti-riot police. We were doing nothing more than shouting slogans, but any of us could have been severely injured or killed—this was not an isolated incident. According to human rights groups, more than 90 people have been killed in the ongoing protests across Iran. The protests were ignited by the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini while she was in the custody of the morality police. The authorities have responded to these protests with a brutal crackdown—beating, shooting, arresting—and an internet blackout that has blocked access to platforms such as WhatsApp and Instagram.

Twenty years ago, it would have been hard to imagine that dozens of cities in Iran would erupt in protests against imposed religious rules. The death of Zahara Bani Yaghuob, an Iranian medical doctor arrested by authorities in Hamedan in 2007, did not lead to widespread protests at the time. But the Iranian state is reaping what they have unintentionally sown. Despite rolling back some women’s rights, such as the Family Protection Law introduced under Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, and imposing an Islamic dress code, after the revolution, a so-called Islamic educational system helped more women in rural and lower social classes to receive an education. While women in upper and middle social classes benefited from progressive laws prior to the revolution, traditional families, typically from disadvantaged backgrounds, felt more comfortable sending their daughters to school under Islamic laws. Today, women account for 60 percent of university students in Iran. It is no coincidence that Generation Z, now on the frontlines of the recent protests, are the children of Iran’s 1980s baby boomers. Generation Z’s parents were the first cohort to see a dramatic shift in the numbers of women receiving higher education in Iran.

A few hours before the tear gas canister nearly struck me on Palestine Street, I was passing security forces on Revolution Avenue when a man in plain clothes and a helmet came up to me and said, “Our cameras will capture your face. If I see you again in this area, you’ll get arrested.” “For what crime?” I asked. “No offence required,” he replied, “I have the power, and I’ll use it against you.”

The man’s boast is the key to understanding the recent protests in Iran. After Sepideh Rashnoo was harassed on a bus by a fellow citizen over her “improper” hijab in July, the dangerous power that had been delegated to pro-regime citizens became clearer. Iranians watched Rashnoo, a writer and artist, make a humiliating forced “confession” on national TV. In contrast to Rashnoo’s humiliation, the woman who harassed her over her hijab enjoyed a kind of authority bestowed upon her by the government.

Along with the morality police, the citizens who have been granted this authority stepped up their policing of the hijab rules since Raisi’s election, which was marred by record low turnout. The death of Mahsa Amini while in police custody has revealed the conflict between the Iranian government and citizens who do not want to comply with rules they believe infringe on their civil rights. There is significant disillusionment and profound doubt about the prospects of reforming a system that has shown zero interest in compromise. If the Green Movement’s slogans were full of verses from Qur’an and other Islamic references, the slogans heard in the recent protests contain no Islamic references and no requests for narrow reforms.

Despite the economic stagnation, systematic corruption, and mismanagement in recent years, economic grievances do not feature in the slogans either. The protests have coalesced around dissatisfaction about how the Iranian state relates to society. The protests that erupted after Mahsa Amini’s death emerged mainly from marginalised groups: Kurds who are an ethnic minority, the middle class which as encountered so much hostility from the government, women who are not even recognised or protected in the system if not wearing a hijab, and the working class who have witnessed widespread governmental corruption in the recent years.

While living under the strict rules of an increasingly authoritarian state, the future for these oppressed groups is grim—they see a dead end. Accordingly, for the Iranian authorities, the unification of these various social groups, which has happened for the first time since the 1979 revolution, poses a new challenge.

In recent years, Iran’s middle class has been shrinking because of international sanctions and economic decline. Still, they have had some spaces, such as social media and satellite television, to engage with progressive ideas on human rights. Long before the recent protests forced Iran’s national television to address the issue of compulsory hijab on their programmes, subjects such as the hijab, personal freedom, and gender politics have been debated on social media and foreign-based television channels before large audiences. In this way, two different worlds have coexisted and one is now crashing into the other.

Are we witnessing another revolution in Iran? It is hard to ascertain. Iran’s state ideology still has sincere supporters, not just at home but also across the region. Some analysts have pointed to the limited number of protesters to suggest the protests are a “virtual revolution” that exists only on social media. Still, a revolutionary turn does not necessarily depend on the number of active protesters; it arises from a dead-end situation. Following Ayatollah Khamenei’s speech in which he called the protests “riots” and blamed a foreign plot for the unrest, the obstruction has never been clearer.

Nevertheless, there is a movement in Iran. Motivated by their anger following Mahsa Amini’s death, a growing number of women who have found the courage to go out with their hair uncovered in public. For a political system that places enormous emphasis on women’s appearance, this is a profound form of protest. Iranian women, supported by the many men who have now joined them, are challenging the discrimination they have experienced for decades. They have already achieved a great victory by making their voice heard around the world.

Photo: EPA-EFE

An Open Letter from 61 Iranian Economists Issues Stark Warning

An open letter co-signed by 61 Iranian economists addresses the government and the Iranian people about the country’s economic challenges.

Editor’s Note: This open letter co-signed by 61 Iranian economists was widely published in Iranian media outlets on June 10, 2022. The letter spurred significant debate and even controversy, with at least one economist claiming they were included as a signatory without foreknowledge of the letter’s content. The letter has been translated here in full in its original form given its insightful diagnosis of the economic challenges facing Iran.

Honorable People of Iran, Dear Compatriots,

Greetings,

When the 13th government took office, electoral rivals were ousted from the country's electoral institutions, bringing apparently uniform governance to the political landscape. In this climate, some analysts predicted, optimistically or naively, an accelerated resolution of the nuclear dispute with the West, as well as the formation of a government backed with maximum support of those holding political power, the military, and the official media in combating corruption, restoring the general business climate, and achieving macroeconomic stability. This was especially the case given that Mr. Raisi's views, programs, and promises as a presidential candidate foretold the formation of an inclusive government that would effectively use the country's vast knowledge and managerial experience. They were reported to have prepared and would implement a 7,000-page reform program with the support of dozens of research institutes and faculties of economics to address critical issues such as inflation, unemployment, and the closure of businesses.

Without tying the nation's livelihood and economy to nuclear negotiations, Mr. Raisi had promised the country would experience 5 percent economic growth, produce one million new jobs and one million new housing units annually, and to rapidly eradicate absolute poverty. He envisaged that the inflation rate would be reduced by 50 percent and then to single digits. Iran's non-oil exports would increase from $35 billion in 2021 to $70 billion in 2022, and the country's total foreign exchange needs would be met using non-oil exports.

In the meantime, many economic and political experts and intellectuals cautioned with foresight and compassion that such promises would not be realisable unless an early agreement was reached in the Vienna talks—after lengthy and exhausting two-year negotiations. Despite under-utilised human and physical capacities, a large number of unfinished projects, and billions of dollars of blocked foreign exchange resources, some of these promises could be fulfilled in the event of a nuclear deal and the FATF's approval, as well as the end of the COVID-19 epidemic; however, their entire fulfilment was also contingent on having good and developmental governance and a well-thought-out plan.

It is unfortunate, however, that since the beginning of April 2022, social unrest and public concern for livelihood and the viability of businesses have reached an explosive stage with the rise in disappointing news reports from the nuclear talks and numerous policy shocks to the country's economy, including the labor and the goods and services markets, followed by the elimination of the preferential exchange rate for essential goods. In the first few months of the year, the inflation and exchange rates have both reached new highs. Official policymakers have referred to the induction of multiple shocks and the escalation of macroeconomic instability as "economic surgery and reform" and "tough decisions for the economy" without considering the far-reaching repercussions of those decisions, the beginning and end, the scope, framework, and depth of this surgery, and its next steps or consequences for the general public. The prerequisites and instruments of economic surgery, such as the structure and function of governance, the attainment of an adequate level of public trust and appreciation, and the establishment of economic stability, were largely disregarded. Despite unofficial restrictions on independent media, numerous experts, economic and social experts, managers, and business owners have issued numerous warnings about the dire consequences of foreign policy inaction and recent ill-considered and erroneous policies over the past few months.

Hereby, the signatories of this letter, a group of economists of the country, convey our scientific analysis, apprehensions, advisories, and some strategies to help amend policies and alleviate the concerns of the dear people of Iran, purely out of a sense of national and social responsibility and moral and professional commitment to the people.

An Overview of the Government's Economic Surgery Policy

After the parliament agreed to eliminate the preferential exchange rate (USD1 = 4,200 tomans), the government's "economic reform" program began on May 9, 2022, with the Presidential TV address. These amendments led to the elimination of the preferential exchange rate for dairy products, animal and poultry feeds, eggs, oil, and certain medicines and medical devices. These items are referred to as essentials in the household basket. Before this decision, pasta, cakes, bulk bread, and confectionery products were taken off the list of items eligible for a preferential exchange rate upon eliminating the subsidy on industrial flour in April.

The government's policy, dubbed "economic surgery,” was rushed into effect without the administrative arrangements necessary to compensate producers and consumers. This may be a transient solution to the pressing budget deficit problem in the face of sanctions and the global food price crisis; it cannot be an economic reform program, however.

The government and parliament have removed the preferential exchange rate of basic goods and introduced it as the beginning of economic surgery. This decision is made while the annual budget contains thousands of billions in tomans for unneeded, nebulous, and removable expenditures, the permanent or temporary omission of which poses no threat to the government's primary missions or the people's general livelihood. Furthermore, this high-risk policy was implemented in the world's most alarming food security circumstances (amid the risk of global hunger and poverty). To date, there is no information on the financial nature of this policy, its resources, expenditures, or the degree of its imbalance. Even for the first time in recent decades, information tables on the sources and expenditures of explicit subsidies (Table 14 of the General Government Budget) and other sections of the Budget Law have not been published, making it impossible to evaluate or comment on them.

Our admonition to government officials is that the country's situation is extremely precarious, and insisting on eliminating subsidies during this miserable time will exhaust the public's patience and turn them against the ruling system and government. This confrontation can be very costly for both sides of the aisle. Reasonably, after the nation's economy and global food markets have returned to normal, macroeconomic stability has been established, and social tensions have been diminished, economic measures such as the unification of exchange rates, reforms in the four markets of the economy, and the organization of consumer subsidies can be implemented, all based on a prudent plan. Likewise, consideration must be given to the support of vulnerable groups in this scenario. At the macroeconomic level, the successful implementation of economic reforms requires certain unavoidable prerequisites, including the following:

Oil and non-oil export revenues, sufficient and reassuring reserves, and the availability of foreign exchange to manage potential fluctuations

Development of vivid and effective policies to stabilise the macroeconomy by regulating inflationary financial and budgetary factors

Low-cost access to global markets, including the market for basic goods and services, and, if necessary, low-cost financing sources and methods

If policymakers insist on continuing this unfortunate and risky practice, the government and the media should take full responsibility, explicitly and courageously, for the policies implemented and all their social and political consequences. Importantly, they should also avoid attributing failures to past pitfalls or the pressures and suggestions of economists outside the government. Nor should they label these suggestions as sabotage against the government and aggressively rebuff the criticisms of experts and those concerned with the national economy. This form and process of policymaking is at odds with, at least, the scientific approaches and indices of Iranian economists.

A Depiction of the Trends of Macroeconomic Indicators and the Outlook for Iran's Development

Development requires a "strong society–strong state" wherein the empowered state lays the foundation (in the form of public and regulatory goods) for the community's empowerment. An empowered society also requires a government that can pave the way for development through development-oriented governance and facilitative policymaking to ensure higher prosperity, employment, comprehensive social justice, security, and tranquility.

According to global comparative reports, indicators of the public business environment, quality of governance, perceptions of corruption, economic competitiveness, property rights, and other factors that lay the groundwork for long-term and inclusive growth and development, are on the decline placing Iran near the bottom of global rankings. Iran, for instance, was ranked 150 out of 180 nations in the most recent survey regarding anti-corruption efforts, and ranked 127 out of approximately 200 countries on the good governance index. In recent years, the social trust index, a measure of social capital that had risen to nearly 70 percent after the Islamic Revolution in 1981 (1360), has plummeted to the very concerning level of approximately 20 percent. The marriage-to-divorce ratio has decreased from 14 percent at the start of the revolution to around 3 percent today.

Due to poor governance, we have been unable to capitalise on the golden opportunities presented by the country's vast human and creative capital, oil revenues, and demographic window so as to achieve rapid economic growth. Oil exports have brought the country over 1.3 trillion dollars since the Revolution began. During this time, the country entered a demographic window in which the population's age structure was more conducive than ever to rapid economic growth. During this period, the country's per capita income has increased by less than 1 percent. Our country is on the verge of a long-term crisis due to the sharp decline in social capital, the inevitable outflows and large-scale layoffs of human capital, the spread of corruption, and the destruction of natural resources and the environment.

Iran's average GDP growth from 1980 to 2018 was approximately 1.6 percent, whereas China, India, Turkey, Malaysia, UAE, and Pakistan averaged between 4 percent and 10 percent during the same period. This meagre growth has occurred despite the fact that, nearly 50 years ago, Iran's economic growth prospects were considered superior to or on par with those of these nations. Due to sluggish economic growth, Iran's share of the global economy has decreased from 1 percent to approximately half a percent over the same period.

In the last decade, Iran's economy experienced the deepest stagflation in 70 years due to oppressive and unprecedented sanctions and the COVID-19 pandemic. The economy was marked by an average growth rate close to zero, an average inflation rate of above 20 percent, a negative and declining rate of gross fixed capital formation—even less than the compensation for depreciation over the past three years—and even more worrisome, an annual financial capital outflow of 10 to 20 billion dollars, depending on optimistic or pessimistic estimates. In the last ten years, the productivity rate of production parameters has been declining in a concerning manner, and the exchange rate has experienced a 30-fold increase (3000 percent). Although the national unemployment rate is still below 10 percent, it exceeds 15 percent in low-income (often border) provinces. In the last four decades, the average inflation rate has been 20 percent, and in the last three years, it has surpassed 35 percent. The misery index is approximately 50 percent, and inflation in 2021 was greater than 40 percent. Iran's imports have decreased from $70 billion in 2011 to approximately $35 billion in 2021 due to the implementation of sanctions and the reduction of oil export revenues.

These deteriorations have resulted in unequal income distribution and the spread of poverty across society. The Iranian Statistics Center has reported that Iran's average Gini coefficient between 2011 and 2018 was 0.408. This metric indicates that Iran is one of the most unequal societies in the Middle East, itself one of the most unequal regions on a global scale, during the relevant period. According to the report, during the same years, 1 percent of Iran's population, comprising the wealthiest strata of society, had an average of 16.3 percent of the country's total income, which is equivalent to 40 percent of the income of the poorest strata. Official reports suggest that the social and prospective outlooks of housing, education, and health inequality are far more unfortunate and worrisome. The Ministry of Cooperatives, Labor, and Social Welfare's report notes that the poverty rate increased from 22 percent in 2017 to 32 percent in 2019 due to the sharp increase in the poverty line basket price between 2018 and 2019. This means that in 2019, 32 percent of the country's population, 26.5 million people, are living below the poverty line, and sadly, estimates indicate that it has extended to nearly 40 percent of Iranian households in 2021. In the last decade, with an economic growth rate close to zero and a population growth of about 13 percent, the average Iranian has become 13 percent poorer. However, inflation and inequality mechanisms such as ineffective redistribution policies and corruption have placed the majority of the burden of poverty on low- and middle-income deciles, low-wage earners, and those employed in the economy's informal sector.

The macroeconomic developments of the past decade, i.e., the period of unprecedented intensification of economic, financial, commercial, and technological sanctions, have had the most significant impact on the living conditions of households and the increase in the poverty rate. Looking into macroeconomic variables has two major implications for Iranians' living conditions: first, a decline in welfare and worsening living conditions across the board for all Iranian households, and second, a more severe decline in welfare in low-income groups (1). Although the legal minimum wage for 2022 increased by 57 percent, the same wage, which fails to account for a large proportion of informal workers, is about $4.7 a day and $1.57 for a family of three. It falls below the international poverty threshold of $2 per day. In addition, many large firms, which are confronted with rapidly rising costs and declining demand, have adjusted their labor force, meaning that workers have been the primary losers of this policy due to their decreased share of national income.

The constant increase in the exchange rate and its inescapable effects on the volume of liquidity, on the one hand, and the reduction of revenue sources and the unorthodox and rapid growth of government expenditures, on the other, have resulted in enormous budget deficits, which are the primary cause of accelerating inflation. The escalating exchange rate-inflation spiral has placed the nation at risk of triple-digit, runaway inflation. Widespread corruption and the collapse of social capital, intensified rent-seeking ties, particularly in foreign trade and financial markets, the sharp decline in investment over the past two decades, and high inflation have cast a shadow over the future of Iran's economy and led to an inevitable, damaging, and irreparable outflow of financial and intellectual capital to other nations.

In recent years, as a result of the rise in the exchange rate and the cancerous growth of the budget deficit, the government has been forced to raise the price of energy carriers on occasion and eliminated the preferential exchange rate for the import of basic commodities this year. Experience has demonstrated, however, that the effects of such policies are extremely short-lived due to pervasive corruption, the collapse of social capital, the increase in the exchange rate, and the budget's ailing structure. Indeed, the budget deficit reoccurs shortly after and at a more considerable scale. Direct subsidies have not helped to offset the decline in public purchasing power and have not prevented the decline in people's livelihoods. Moreover, the government's monetary and fiscal policies have exacerbated the widening divergence.

In summary, the economic situation in Iran is very concerning, based on an abundance of evidence, and there seems to be no prospect of improvement or departure from this current state. Indeed, the downward trend of institutional performance indices (such as quality of governance, general business environment, corruption, economic competitiveness, and innovation), as well as other key parameters such as the outflow of financial and human capitals and the declining rate of economic investments over the past few years, is a substantially more ominous sign for the Iranian economy in future.

Honourble and patient people of Iran,

Dear Iranians,

Regrettably, the indicators and evidence presented above are not simply numbers on a page; they tell a heartbreaking story of hopelessness, the absence of a bright horizon, a lack of a favourable environment for production and business enterprises, a steady decline in people's purchasing power, growing poverty, and shrinking livelihoods. The obvious outcome of long-term exposure to such high inflation and a steadily rising exchange rate is a sense of social powerlessness and gradual decline. Inequality and income and asset gaps resulting from inflation, corruption, or dysfunctional fiscal and monetary policies, have turned trust and coexistence between the winners and losers of this bitter game into hatred and resentment, causing social capital to be shattered and destroyed. On the other hand, in the current state of the country, where economic and social policies are shrouded in secrecy, any criticism of the government is interpreted as part of a malicious plot against the governing system, making it difficult for experts or academic circles to raise such issues openly. Even more difficult is persuading the rulers and policymakers to accept that the Iranian people's suffering is now due to their long-term ineptitude and mismanagement.

It would be too naive to attribute this disorderliness solely to economic and financial factors such as large and growing budget deficits. Our economic and social problems—including the destruction of natural and environmental resources, systematic corruption, the destruction of social capital, the massive migration of human and innovative capital, the outflow of financial capital, the budget deficit and even the sanctions—are in a more general analysis, the product of poor governance and disregard for the scientific foundations of public policy.

If only our policymakers could foresee that now is not the time for a tug-of-war and coercive measures on national and global scales.

If only the esteemed President knew that economic policy is not the venue for an apprenticeship, trial and error, hasty decisions, or unthoughtful manipulations of prices and mediating factors. In fact, having the trust and the psychological and social support of society, having a stable environment based on international cooperation and coexistence, and having a strong bureaucracy equipped with modern knowledge and technology, are some necessary requirements for reforms or, in their own words, "economic surgery."

Dear compatriots,

Based on a review of global experiences and the scientific analysis of national experts and signatories of this letter, the first step to escape this dilemma is to fundamentally alter the nation's foreign strategies and policies, and the second is to alter the manner in which the country is governed. Two long leaps should be taken to solve Iran's complex economic and social issues and compensate for its stagnation in global economic competition:

Fundamental reforms in foreign policy by adopting a policy of peaceful coexistence and dignified cooperation with the countries in the region and especially neighbouring countries, as well as balanced and active interaction with major economic powers; also, paying attention to the minimum demands of the honourable people of Iran to improve the living conditions of Iranian people and to promote Iran's position globally. Without restoring the JCPOA and removing FATF-imposed restrictions on the Iranian banking sector, it is pointless to address macroeconomic stability policy and low-cost access to global markets.

Without an improvement in the quality of governance, economic surgery or reform will result in pervasive corruption, irreparable poverty and inequality, and deteriorating social and political stability. The prerequisites for effective governance and vital reforms are as follows:

Improving the quality of governance, the absolute and unequivocal rule of law at all levels, and government accountability for its decisions and public demands

Minimising political and economic corruption by applying maximum transparency mechanisms to the processes and outcomes of all policies, decisions, allotments, and appointments

Establishing an impartial, wholesome, accessible, affordable, and dependable judicial system for all social groups

Accepting and assisting in the creation of a space for dialogue, criticism, and oversight for scientific associations, universities, civic institutions, specialised and professional inclusive organisations, and independent media, and committing to the rules and goals of such a cause in practice

Possessing a robust and accountable executive and bureaucratic system with convenient and trustworthy databases

Possessing updated and potent information and communication technologies to implement targeted support and subsidy programs, carry out specific payments for specific target groups, and purchase specific goods and services from specific centres at specific times

Establishing and expanding the coverage of the welfare and social security system and efficient health insurance through equitable and efficient taxation (not by doubling the financial pressure on the critical sources of pension funds)

Fostering a competitive environment for the private sector's entrepreneurs and business owners while avoiding government monopolies or security conditions in the marketplace

Conceiving and implementing a production-focused incentive system that encourages the manufacturing sector and restricts destructive and unproductive activities

For policymakers and government officials to address the current turmoil, some clear implementation plans are also proposed:

It is incumbent upon the President and his principal colleagues to report on economic policies and programs, as well as their resources and expenditures, unambiguously and vividly, to seek consultation and advice from knowledgeable and specialised individuals, and to courageously take responsibility for their decisions.

A report on the sources and expenditures of the newly established subsidy, the number of households covered by it, and this year's budget imbalance should be publicised officially and transparently. A program of maximum financial discipline should be formulated, published, and implemented, including a revision of the 2022 budget based on public interests rather than the interests of specific groups. More specifically, the government should eliminate budget lines involving rents and overt and covert support for specific groups and centres, the removal of which has no harm to the essential activities of the government in exercising its sovereignty and public welfare provision.

A preferential exchange rate should be provided for the import of basic commodities, particularly wheat (until global food security concerns are resolved) and medicine (until compensatory mechanisms in the social security system are established), and any decisions or policies that involve price shocks upsetting the balance for vulnerable groups should be avoided.

In certain instances, cash subsidies intended to offset the negative effects of pricing policies are ineffective. It is imperative to build on up-to-date information and new information technologies, as well as close collaboration between the banking system and the goods distribution system, to allocate the payment subsidy in an entirely purposeful way for purchasing basic goods and ensuring food security in pre-specified purchase terminals.

The government monopoly on importing basic goods should be reformed into an effective competition. Accordingly, in addition to state-owned companies, all known and authorised traders should be permitted to purchase and import the basic goods required by the country from international markets in any quantity using export currency so as to maintain a sufficient level of strategic stocks of goods.

Concluding Remarks

To put it bluntly, successful price reforms necessitate broad government accountability, citizen participation in decision-making, the application of elite knowledge, and extensive communication with the rest of the world based on global standards.

Ultimately, while emphasising the motivation of the signatories of this letter to assist in resolving the current turmoil for the benefit of the people, we request that expert criticism be given due consideration.

With the people are God's hands.

Tomorrow, when the vestibule of truth becometh revealed,

Ashamed the way-farer, who, illusory work, made.

The List of Signatories of the Statement of Economists Addressed to the Honourable People of Iran

1. Ebrahimi Taghi, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad

2. Arbab Hamidreza, Allameh Tabataba’i University

3. Asgharpour Hossein, University of Tabriz

4. Afghah Morteza, Chamran University of Ahwaz

5. Akbari Nematollah, University of Isfahan

6. Elahi Naser, Mofid University

7. Emamverdi Ghodratollah, Azad University of Tehran

8. Amin Ismaili Hamid, Jihad Daneshgahi Institution

9. Amini Minoo, Payam Noor University, Tehran Branch

10. Olad Mahmud, Urban Economics

11. Ahangari Abdolmajid, Chamran University of Ahwaz

12. Bagheri Mojtaba, Mofid University

13. Bakhshi Lotfali, Allameh Tabataba’i University

14. Behboodi Davoud, University of Tabriz

15. Beheshti Mohammadbagher, University of Tabriz

16. Pazooki Mehdi , Planning Organization

17. Pishbin Jahanmir, Chamran University of Ahwaz

18. Tahsili Hasan, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad

19. Takieh Mehdi, Allameh Tabataba’i University

20. Chinichian Morteza, Allameh Tabataba’i University

21. Hosseini Seyed Mohammad, Research Institute of Islamic Sciences and Culture

22. Khatayi Mahmud, Allameh Tabataba’i University

23. Khodaparast Mehdi, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad

24. Khalili Tehrani Abdolamir, Shahid Beheshti University

25. Dadgar Yadollah, Shahid Beheshti University

26. Delangizan Sohrab, Razi University

27. Dahmardeh Nazar, University of Sistan and Baluchestan

28. Dehkordi Parvaneh, Payam Noor University, Tehran Branch

29. Rahdari Morad, Payam Noor University, Tehran Branch

30. Satarifar Mahommad, Allameh Tabataba’i University

31. Sahabi Bahram, Tarbiat Modares University

32. Shajari Hushang, University of Esfahan

33. Sharif Mostafa, Allameh Tabataba’i University

34. Sharifzadegan Mohammad Hossein, Shahid Beheshti University

35. Sadeghi Tehrani Ali, Allameh Tabatabai University

36. Sadeghi Saqdel Hossein, Tarbiat Modares University

37. Taheri Abdollah, Allameh Tabataba’i University

38. Asi Reza, Allameh Tabataba’i University

39. Ebadi Jafar, University of Tehran

40. Azizi Ahmad, Former Deputy of Currencies of the Central Bank and University Lecturer

41. Asari Arani Abbas, Tarbiat Modares University

42. Isazadeh Saeed, Bu Ali University

43. Firoozan Tohid, Kharazmi University

44. Ghanbari Hasanali, Shahid Beheshti University

45. Ghanbari Ali, Tarbiat Modares University

46. Karimi Zahra, Mazandaran University

47. Kia Al-Husseini Seyed Ziaoddin, Mofid University

48. Lashkari Mohammad, Payam Noor University, Mashhad Branch

49. Mohammadzadeh Parviz, University of Tabriz

50. Maziki Ali, Allameh Tabataba’i University

51. Mostafavi Mehdi, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad

52. Mostafavi Montazeri Sayyed Hassan, Tarbiat Modares University

53. Monsef Abdolali, Payam Noor University, Tehran Branch

54. Musaei Meysam, University of Tehran

55. Mousavi Mirhossein, Al-Zahra University

56. Mousavi Habib, Azad University of Arak

57. Mirzaei Hujjatullah, Allameh Tabataba’i University

58. Mehdikhani Alireza, Azad University of Arak

59. Hadi Zanouz Behrouz, Allameh Tabataba’i University

60. Varhami Vida, Shahid Beheshti University

61. Yusefi Muhammad Raza, Mofid University

Is Iran's 'Bread' Subsidy Reform a Half-Baked Idea?

A new round of protests has begun in Iran. People are taking to the streets following a controversial subsidy cut perceived as an increase in the price of bread.

A new round of protests has begun in Iran. People are taking to the streets following a controversial subsidy cut perceived as an increase in the price of bread. These protests were inevitable in a country in which there are so many economic and political grievances and in which civil society and labour groups, demoralised about their ability to influence policymaking through the ballot box, have turned to mobilisations to get their voices heard and their anger registered.

The policy that has triggered the protests has been widely reported as a cut to a “bread subsidy” that has suddenly increased the cost of bread and cereal-based products. This is inaccurate. The subsidy that has been eliminated was an exchange rate subsidy. The government had been providing Iranian importers allocations of hard currency below market prices. This policy indirectly subsidised the purchase of wheat and a few other foodstuffs by the importers. It did not directly subsidise the purchase of bread by ordinary people.

Importers could apply for foreign exchange allocations from the Central Bank of Iran to import wheat. In theory, this would allow them to bring wheat to the Iranian market at a lower price. But in practice, the subsidy had long ago stopped working. Several distortionary effects of the policy were likely generating inflationary pressure across the economy.

First, the exchange rate subsidy was poorly targeted. To put it simply, the Iranian government was intervening to make foreign money cheaper, not bread prices themselves. The subsidy was therefore ill-suited to stabilise prices when Iran’s import needs rose, a periodic occurrence when the domestic harvest falls short of targets. It was also unable to counteract the effects of global increases in the price of wheat. Breads and cereals prices have risen steadily in Iran for years, quadrupling since 2018.

Second, providing foreign exchange at a subsidised rate was exacerbating Iran’s fiscal deficit. Financing this deficit is a major driver of inflation in Iran. The official subsidised exchange rate diverged from the exchange rate on which Iran’s government budget is balanced in 2015. Since then, the spread between the two rates has increased dramatically. The subsidised exchange rate has been fixed at IRR 42,000 since 2019. The exchange rate in the Iranian government budget for the year beginning March 2022 is IRR 230,000. As this spread widened, the Central Bank of Iran faced increasing difficulty in meeting demand among importers for subsidised foreign exchange, creating a foreign exchange liquidity crunch that made it harder to stabilise Iran’s currency outright. In recent years, the Iranian government was spending around $12 billion in hard currency on a subsidised basis.

Third, this additional exchange rate volatility has increased the pass-through effects related to Iran’s dependence on imports more broadly. The Central Bank of Iran has had partial success in stabilising the exchange rate by introducing a centralised foreign exchange market for importers and exporters called NIMA. But Iran’s economic policymakers were tying their own hands in the stabilisation of this exchange rate, which is far more critical for Iran’s economic performance, by diverting precious foreign exchange resources towards essential goods importers. When it comes to inflation generally, the government ought to focus on intermediate goods on which “made in Iran” products depend. The exchange rate subsidy for essential goods was making it harder to stabilise the exchange rate for all other goods.

Fourth, the exchange rate subsidy was always subject to abuse. Particularly in the early years, importers were known to seek and receive allocations of subsidised foreign exchange and either pocket those allocations or turn around and sell on the hard currency to other firms at the market rate. This kind of profiteering was difficult to police. As more scrutiny came upon the allocations, importers with political connections were most likely to continue receiving allocations from the Central Bank of Iran, making enforcement politically fraught.

The evidence that the exchange rate subsidy had failed can be seen in consumer price index data. Bread and cereals inflation has outpaced general inflation since last summer. This is a likely reflection that, in practice, a diminishing volume of wheat imports were being conducted using the subsidised exchange rate—the reform was already being priced-in by the newly elected Raisi government. The sudden price increases were are seeing now are more likely the result of price gouging. Firms across the food supply chain are using the policy reform as an opportunity to raise prices, knowing the blame will be cast on the government.

Whether or not the reform is half-baked, the idea has been cooking in the oven for a long time. The subsidy cut was years in the making and the preferential exchange rate was nearly nixed in 2019, as the Iranian economy underwent a painful adjustment following the reimposition of U.S. secondary sanctions. At the time, the Iran Chamber of Commerce, the voice of the country’s private sector, issued a strong statement calling for the elimination of the subsidy. But the reform was eventually shelved—the Rouhani administration had been cowered by the 2017 and 2018 economic protests, which were instrumentalised by their political rivals.

In the end, the Central Bank of Iran took a different tack. They kept the exchange rate in place but began to eliminate the range of imports eligible for the rate. Initially, importers could apply for subsidised foreign exchange allocations for the purchase of 25 essential goods and commodities. As of September 2021, that list was cut down to just seven goods—wheat, corn, barley, oilseeds, edible oil, soybeans and certain medical goods.

These were preparatory steps for the elimination of the subsidy. In practice, many Iranian grain importers had stopped using the subsidised exchange rate, both in anticipation of its elimination and because it was impractical. One of the fundamental problems facing Iran’s food supply chain is that even when Iranian importers can identify buyers and arrange logistics—difficult things to do when under sanctions—the payments that need to be made for those purchases are often delayed. Importers that were applying to the Central Bank of Iran for allocations of subsidised foreign exchange might wait weeks before the money hit their accounts. Cargo ships would sit idle off Iran’s shores, unable to deliver the grain until the seller received their funds. These delays added costs. The Iranian importers were on the hook for huge fees as the ships they chartered remained out of service. Importers that opted to use the NIMA rate have been able to make payments to their suppliers more quickly and reliably. This is because there is far more liquidity in the NIMA market, in which foreign exchange is supplied by Iranian exporters who are repatriating their export revenues as required by law.

Overall, there is a sound economic argument for eliminating the subsidised exchange rate. But that does not mean that there will not be pain for ordinary people in the short term and the protests are motivated in part by an expectation of further pain. The abject failure to communicate a plan around the subsidy reform will lead to its own distortionary effects, including predatory pricing. Failing to communicate directly and clearly with the Iranian public about this major reform is its own kind of contempt, even if the reform itself is not contemptuous.

In that vein, the elimination of the subsidised exchange rate has been criticised as “neoliberal” and in many respects, it is. As part of the continuity in economic policy, the Raisi administration appears to be continuing the Rouhani administration’s commitment to austerity, seeking relief from inflation through fiscal tightening. The national protests in 2017 and 2018 were triggered by the same anxieties around the government’s perceived failure to protect economic welfare within the Islamic Republic’s social contract.

But on the other hand, this is not a simple economic reform. Iranian officials have likened it to “economic surgery” necessary to repair an economy weakened by sanctions. The reform also does not preclude other redistributive policies. The subsidised exchange rate was a poorly designed and inefficient policy that did more for a small number of elites than it did for Iran’s poor.

The Raisi administration has promised to soften the blow of the reform by providing targeted cash transfers (for two months) to the most vulnerable in Iranian society. Electronic coupons are also being provided. Iran has a good track record with cash transfers, which do something the exchange rate subsidy did not. Such transfers directly boost the consumption of ordinary people in the face of rising prices. If the government can use the fiscal savings from the elimination of an inefficient and poorly targeted policy to shore the economic welfare of Iran’s poor more directly, while also addressing long-running distortions in the foreign exchange markets, this reform may succeed yet. But if the government fails to communicate clearly about its implementation of the reform, the Iranian public will continue to only see failure.

Photo: IRNA

Qatar and Iran Devise Game Plan for the 2022 World Cup

Qatar’s transport minister made a two-day trip to Iran’s Kish Island, during which officials and businesspersons from both countries explored possible teamwork as Qatar prepares to host the 2022 World Cup.

In just the last two months, Iran and Qatar have signed 20 bilateral agreements—14 were signed during Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi’s trip to Doha in February, and another six were signed when Qatari transport minister, Jassim bin Saif Al Sulaiti, traveled to Kish Island earlier this week. Among the 20 agreements, Iran and Qatar decided to waive visa requirements for the citizens of both countries, expand transportation links by air and sea, find practical ways in which Kish and other Iranian islands and free zones can play a role during the 2022 World Cup, increase trade through commercial ports, and link free zones. Moreover, Raisi proposed the establishment of an Iran Trade Center in Qatar “to introduce Iran’s capacities and potentials to Qatari merchants and economic actors.”

During his two-day visit to the island of Kish, an Iranian resort destination located just 270 kilometres from Doha, Al Sulaiti was hosted by Iran’s Minister of Roads and Urban Development, Rostam Ghasemi. The Iranian government has made Kish the focal point of its offer to assist Qatar during the hosting of the 2022 World Cup. The trip included visits to the port of Kish Island and the Kish International Airport expansion project, as well as some of the sporting facilities located on the island. Aside from the prospects for the World Cup, Iranian and Qatari delegations are hoping for expanded connectivity between the island and Doha to enable more trade and tourism. Al-Sulaiti and his delegation also met onetime presidential hopeful Saeed Mohammad, the former head of Khatam al-Anbiya, a major IRGC-linked construction firm. Mohammad is now the head of the Supreme Council of Free Trade-Industrial and Special Economic Zones.

Iranian officials have ambitious plans for the 2022 World Cup—which may prove difficult to realise. While the tournament will be hosted by Qatar alone, there is potential for other countries in the region to play a role by accommodating teams and tourists, particularly given capacity constraints in Qatar itself. Iran cannot offer the leisure experiences that many football fans will expect during their trip, but Iranian officials hope that those fans seeking to justify the journey to Qatar with more cultural and natural attractions could be drawn to Iran. Officials want to “create the grounds for foreign fans and tourists to travel to [mainland] Iran during their leisure times” stated Ghasemi.

Under the proposed plans, tourists could visit Kish and either decide to stay on the island for the entirety of their trip or obtain a visa to visit other Iranian cities. Leila Azhdari, the official in charge of foreign tourism at Iran’s tourism ministry, has stated that “the foreign ministry had agreed to waive visas for travel from Qatar for two months during the World Cup, which will end on December 18.” According to the plan, tourists will be able to apply for “free single or multiple-entry passes for 20-day stays” during the World Cup.

Even if a visa scheme can be devised, logistical challenges will remain. Currently, there are no flights from Kish to Doha. While there were talks of Kish Air trying to establish a route from Kish to Doha from 2018, this route was never launched. Just last month, Mohammad claimed that there will be 400 weekly flights from Kish to Doha during the World Cup and they are in talks to secure four cruise ships to ferry passengers during that period. There is currently only one established ferry route that goes from Bushehr to Doha, owing to the fact that marine diesel is not subsidised by Iran and so operating these routes is less economical.

A lack of transport infrastructure has not prevented private sector entrepreneurs and Kish’s local government from preparing for the World Cup. In January 2020 a special committee was formed by the management of the Kish Free Zone Organization and a budget of IRR 520 billion (approx. $2 million) was allocated to standardise two existing football fields and to build three new ones. The committee also targeted the completion of new five five-star hotels by November. According to Masihollah Safa, Chairman of the Association for Hotel Owners in Kish, there are 52 hotels in total on the island with 12,000 rooms in four- or five-star hotels and another 8000 rooms in budget accommodations and unofficial housing that could be used during the World Cup.

Kish is also being promoted as a destination for Iranians inside and outside the country seeking accommodation during the World Cup. Iran is playing in the tournament on November 21, 25, and 29, meaning that if fans wish to watch all three matches in the group stage, they must stay in Doha for at least nine nights. The expense of such a trip may be prohibitive for many Iranians and most Iranians do not have international bank cards. Using Kish as a gateway will allow Iranian fans to book travel packages that include transportation, accommodation, and game tickets. These packages include options for return flights on the day of the matches so that the fans do not need to secure accommodation in Doha.

The Kish Free Zone Organization is also organising a soccer festival during the 2022 World Cup and is attempting to secure an agreement with the Iranian national team to host their training camp on the island, according to Mohsen Gharib, Chairman of the Association of Investors in Kish. The island is also being put forward as a possible base camp for other national teams competing in Qatar.

Al Sulaiti’s visit to Kish appears to have been successful. Businessmen who attended the meetings between Iranian and Qatari government officials were generally pleased with the fact that relations between the two countries have been elevated to this level. Some business leaders are concerned that politically connected firms might crowd-out private businesses seeking to engage with Qatari counterparts.

I spoke to Iran’s Ambassador to Qatar, Hamidreza Dehghani, following the Qatari delegation’s visit to Kish. He acknowledged the many remaining hurdles facing both the potential role for Kish during the World Cup and also for the future of trade and economic relations between Doha and Tehran. Finding alternative modes of payment for foreigners and solutions for the issue with visas were top of his mind. More importantly, he believed that work must be done to counter the negative perceptions toward Iran if it is to be an attractive destination for foreigners.

But there is optimism that the strong relations between the Iranian and Qatari governments might finally translate into mutually beneficial economic engagements as diplomatic dialogue is increasingly focused on questions of regional economic integration. More than four decades since it was first touted as a resort destination, Kish might finally have its moment.

Photo: IRNA

Trade, Not Investment, is Iran's Sanctions Relief Must-Have

Sanctions relief will enable Iran to buy the industrial goods that will undergird the country’s economic resilience for the next two decades.

Last week, the seventh round of the negotiations over the fate of the JCPOA saw Iran table an initial proposal on sanctions relief. The proposal led to complaints from Western officials that the Iranian negotiators were being unreasonable. Iranian officials responded by insisting their proposals were “pragmatic.” The initial exchange suggested to some that disagreements over sanctions relief issue are going to prove the intractable because what Iran wants—significant investment—is impossible for the P5+1 to guarantee. Gérard Araud, former French ambassador to the United States and an astute observer of the nuclear talks, tweeted that “Even if the JCPOA was restored, no Western company would dare invest a cent in Iran.”

Araud is rightly concerned. Western companies will be reluctant to invest in Iran due to fears that a Republican president could reimpose sanctions in 2025, putting their investments in jeopardy. In the months following the implementation of the JCPOA in January 2016, a flurry of big-ticket investment deals were announced. These deals became the symbols of the economic benefits of sanctions relief and of Iran’s moves towards normalised economic relations, namely with Europe and China. The deals included planned investments in Iran’s oil fields by Total and CNPC, the joint ventures planned by PSA Group and Volkswagen in Iran’s automotive sector, and Novo Nordisk’s decision to build a manufacturing plant in Iran, among others. But following President Trump’s decision to withdraw from the nuclear deal, essentially all European and Chinese efforts to invest in Iran unravelled (the Novo Nordisk project, with its humanitarian dimension, proved a rare exception).

For the P5+1, a significant technical interventions will be necessary to create conditions conducive to foreign direct investment. But, the economic value of the nuclear deal does not actually hinge on increased foreign direct investment, which was primarily sought by Iran as a commitment mechanism for technology transfer.

But for most Iranian manufacturers, the ambition is not to produce high-technology products. Rather, the ambition is to use high-technology equipment to more efficiently produce the wide range of basic goods that can be sold in the domestic and regional markets. Iran will receive most of the benefits on offer from sanctions relief when Iranian manufacturing firms can purchase new equipment from foreign suppliers that can be used to increase the quality and quantity of output. Such purchases represent a critical example of domestic investment deferred due to sanctions related pressures.

The industrial equipment on which Iranian factories depend is overwhelmingly imported from just two sources: the European Union and China. This trade can be tracked by looking at the relevant chapters of the so-called Harmonized System used by customs agencies categorise goods. Chapter 84 covers equipment such as boilers, pumps, turbines, furnaces, freezers, ovens, pulleys, cranes, forklifts, and other machinery that would be seen on a factory floor. Chapter 85 covers electrical equipment such as motors fuses, switches, lasers, heaters, magnets, batteries with various industrial applications. Looking at European and Chinese exports to Iran across these two categories offers a measure of whether Iranian factories are proving able to maintain or upgrade the equipment on their assembly lines. What’s clear is that sanctions significantly reduced European and Chinese exports of these goods to Iran, with significant consequences for Iranian productivity. Between the first quarter of 2018, prior to Trump’s withdrawal from JCPOA, and the last quarter of the year, by which point US secondary sanctions had been reimposed in full, Iran’s industrial output fell by 20 percent.

Part of the drop in production can be attributed to reduced demand. But many manufacturing firms also struggled to maintain output given difficulties not only in importing raw materials and intermediate goods, but also the parts and equipment necessary to keep assembly lines running at high capacity. Moreover, it wasn’t the wind down of foreign investment that was responsible for the drop in production—few investment projects had broken ground. Rather, it was disruption in the availability of European and Chinese industrial goods that saw Iran’s manufacturing sector regress.

In 2016, the first year of sanctions relief, European industrial exports to Iran averaged EUR 250 million per month. Over the first 8 months of 2021, the monthly average has been just EUR 80 million. That means, on an annualised basis, Iran is importing about EUR 2 billion less industrial goods from Europe than prior to the reimposition of US secondary sanctions.

The trends are similar when looking at Chinese exports to Iran. In 2016, average monthly exports to Iran totalled about USD 453 million. Over the first 10 months of 2021, the monthly average has been just USD 241 million. On an annualised basis, that is a difference of about USD 2.5 billion.

Looking at the European and Chinese data together suggests that sanctions relief could be worth around USD 4.8 billion in additional annual industrial exports to Iran from its two largest suppliers, if trade returns to pre-sanctions levels. A significant portion of the goods imported in these two categories are purchased as part of fixed capital investments by Iranian manufacturing companies, meaning that Iranian firms can be expected to invest billions of dollars in their own production capacity if sanctions are lifted and European and Chinese exports rebound.

Such a rebound is probable. For European and Chinese companies, the decision to enter the Iranian market as a supplier is far less risky than the decision to enter as an investor. Even with concerns that JCPOA implementation may falter again in 2025, the data from 2016-2017 makes clear that trade in industrial goods can rebound quickly, even in an environment where banking challenges and legal ambiguities persist. Many European and Chinese companies will be able to make lucrative sales to Iranian customers within the 2-3 year window in which sanctions relief is basically assured, especially those suppliers who are currently selling to Iran while US secondary sanctions remain in place.

Importantly, the fact that trade in industrial goods can rebound in a short period of time does not mean that the benefits will be short-lived. Equipment like pumps and furnaces have lifespans up to 20 years. Many Iranian factories are hampered with old equipment. Sanctions relief would enable these firms to finally upgrade old equipment, much of which was installed in the early 2000s during which Iranian industry underwent a critical development phase characterised by the installation of European manufacturing equipment. Should more Iranian companies be able to avail themselves of the opportunity to invest in new industrial equipment following the restoration of the JCPOA, Iran industrial output would benefit from higher productivity and greater resilience for a decade or longer, a fact that makes sanctions relief, even if cut short by political events, fundamentally attractive.

Economically speaking, trade, not investment, is the key for robust Iranian growth in the years immediately following restoration of the JCPOA. Attracting foreign direct investment would of course maximise Iran’s developmental outcomes, and has a crucial role to pay should Iran aim to return to its pre-sanctions growth trajectory, but such investment is not essential for Iran’s short-term economic recovery. The primary goal for the P5+1 should be to ensure that trade rebounds as quickly and robustly as possible. Here, the provision of trade finance is important and technical work will need to be done to ensure that global export credit agencies can serve companies that wish to sell equipment to Iran. Still, finding solutions to extend billions in trade finance will prove far easier than facilitating billions in foreign direct investment in the short term.

Politically, facilitating foreign direct investment would usefully demonstrate that the P5+1 is making good on economic commitments set forth in the JCPOA. On one hand, the Raisi administration would surely welcome more intensive efforts on the part of Western governments to ensure foreign investments can materialise, particular in sectors where such investment is really necessary like the energy sector. On the other hand, the fact that trade, and not investment, is the real economic must-have will suit the Raisi administration just fine. President Raisi is unlikely to make Western foreign investment a major target of JCPOA implementation given the emphasis on economic self-reliance that colours his administration’s economic planning and the reluctance to undertake deeper structural reforms on which many foreign investors will insist. But by focusing on trade, Raisi will have a compelling story to tell—sanctions relief will enable Iran to buy the industrial goods that will undergird the country’s economic resilience for the next two decades.

Photo: IRNA

Iran’s Emboldened Workers Press New President for More Concessions

A wide range of social groups in Iran have been mobilising to express their socioeconomic grievances. Grappling with concessions made by the previous administration, Iran’s new president is on the back foot.

In the third week of September, teachers in dozens of towns and cities across Iran took to the streets, calling on the new president, Ebrahim Raisi, to fully implement existing labour laws. The authorities responded quickly and positively, promising to work on an implementation plan. But the teachers are not ready to back down. In an interview conducted for this article, a leader of the main teachers’ union said his organization will continue to use a “carrot and stick” approach to ensure that the Raisi administration makes good on its promises.

The latest nationwide demonstrations by teachers are part of a bigger protest wave that has gripped Iran over the past year. In the first few months of the year, pensioners mobilised in Tehran and other major cities. In July, residents of the southern province of Khuzestan protested water shortages. Between June and August, contract workers across Iran’s oil sector staged intermittent strikes and demonstrations. These protests are unlikely to let up. A wide range of social groups have been mobilising—organising locally, regionally, and nationally—to express socioeconomic grievances.

As these protests have continued, the Raisi administration has defied predictions that it would quickly impose order on Iran’s restless society. Raisi was elected president in June after extensive electoral manipulation and a record low turnout. But that Iran’s new leadership came to power with little regard for the electorate has not dissuaded protestors from making demands of state authorities. According to one protest tracker, September—Raisi’s first full month in office—saw one of the highest number of protest events in the past year.

Raisi has been forced to grapple with the promises made by his predecessor, Hassan Rouhani. Rouhani launched his first term with a vow to bring inflation under control and spend government resources prudently. He exited office last August having promised financial support to a wide range of groups and sectors. Rouhani’s commitment to inflation reduction was sincere and, initially, successful. After carefully and painstakingly negotiating sanctions relief and rebalancing the economy between 2013 and 2017, his successes were quickly undone by the twin shocks of the Trump administration’s reimposition of sanctions in May 2018 and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in February 2020. Realising that fiscal prudence would not be enough to shore the Iranian economy, Rouhani decided to direct spending towards his core constituents, namely the urban middle classes.