How Trump Can Strike Gold for America in Iran

Trump loves gold. If he remains pragmatic and focused when it comes to Iran, he could strike gold in several ways.

There is a curious line in the Omani statement issued following the latest round of nuclear negotiations between the United States and Iran in Rome, which concluded on Saturday. The statement declares that Iran’s foreign minister, Abbas Araghchi, and Trump’s special envoy, Steve Witkoff aim to “seal a fair, enduring and binding deal which will ensure Iran [is] completely free of nuclear weapons and sanctions.” The sentence is striking because it implies that the US is considering lifting primary as well as secondary sanctions, something that goes beyond the sanctions relief provided under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA).

Is this just a case of sloppy drafting by the usually diligent Omani mediators? Well, the Wall Street Journal has reported that Iran has offered Trump a high-level meeting in Washington if a deal can be reached, something that would be difficult to imagine if Iran were to remain under an effective US embargo after the deal’s implementation.

Iranian officials have certainly been touting the possible economic benefits of a renewed nuclear deal for the US. When Araghchi described Iran as a “trillion-dollar opportunity” in a recent op-ed, he had one investor in mind—Donald Trump. As the US and Iran take further steps in the nuclear negotiations, Iranian officials have been eager to make clear that agreeing a new nuclear deal, which would at a minimum require the US to lift secondary sanctions on Iran, could prove a boon not just for the Iranian economy but also for the American economy. To emphasize the point, Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian even announced that Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, has “no objection” to American investment in Iran—an attempt to conjure a positive atmosphere ahead of the first round of indirect talks between Araghchi and Witkoff in Muscat.

It remains unclear whether the Trump administration will be able to achieve a viable deal with Iran. The administration’s position on key issues, such as Iran’s ability to maintain uranium enrichment, remains ambiguous, and there is significant distrust on both sides. If the negotiations are to succeed, they will need to find a win-win formula—hence the Iranian insistence on portraying any new agreement as not just a nuclear deal, but also a business deal. Iranian leaders have been watching Trump’s recent moves—his aggressive use of tariffs, his imposition of a critical mineral deal on Ukraine—and they have smartly concluded that Trump cares more about American enrichment than Iranian enrichment.

Is Iran really open for American businesses? The answer is yes, especially if Iranian and American policymakers make the restoration of their bilateral economic relationship a priority alongside restoration of a nuclear deal. Lifting primary sanctions would have a dramatic impact on US-Iran economic relations. But even if those sanctions remain in place, there are ways in which the US and Iran can structure their bilateral economic relations, opening new channels for trade and investment.

The heyday of US-Iran economic relations dates to the 1960s and 1970s. American firms like General Electric, General Motors, and DuPont played a central role in Iran’s industrialization, helping the country’s oil and manufacturing sectors achieve global prominence. Consumer brands like Gillette, Colgate, and Coca‐Cola were beloved by Iranian households.

The 1979 Islamic Revolution brought an end to diplomatic relations between the United States and Iran. That year, the US imposed sanctions targeting the Iranian economy for the first time. The New York Times reported on the exodus of American firms from Iran with a report titled, “Iranian Festival Is Over For American Business.”

But the change in Iran’s geopolitical and ideological orientation did not change a basic economic reality—the 1990s were an era of unipolarity and it was prudent to do business with the world’s largest economy. Iranian President Hashemi Rafsanjani tried to rekindle economic relations with the United States, believing that higher levels of trade and investment would help restore relations between the two countries. He offered the Islamic Republic’s first post-revolution oil field development contract to ConocoPhillips, maneuvering around domestic opposition to the deal. But the deal was blocked by the Clinton administration, which subsequently tightened US sanctions on Iran. The episode served as an early warning that the hardliners most capable of thwarting diplomacy were those in Washington, not Tehran.

American firms maintained a small presence in Iran in the early 2000s while European firms emerged as Iran’s preferred partners. The Europeans established joint ventures and wholly owned subsidiaries in the country and did brisk business. French oil giant Total took over the deal first offered to Conoco-Philips. French and German automakers retooled the Iranian automotive industry, making it one of the largest in the world. European brands flew off supermarket shelves as Iranian household purchasing power recovered on the back of 16 consecutive years of economic growth.

Iran’s economy hit a stumbling block in 2012 as the international community tightened international sanctions—with the measures hinging on President Obama’s unprecedented package of financial sanctions imposed at the start of that year. Subsequent nuclear negotiations focused on restoring Iran’s trade and investment ties with Europe, but the Obama administration did understand that enabling more trade between the US and Iran could create broader constituencies in Washington who backed the JCPOA, which was implemented in January 2016.

While primary sanctions remained in place after implementation of the deal, the JCPOA opened three pathways for US business that wished to pursue opportunities in Iran. First, certain US companies were able to apply for specific licenses from the Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC), part of the Treasury Department, permitting deals that would otherwise be blocked by primary or secondary sanctions. Among the contracts licensed in this way were the roughly $20 billion in deals Boeing negotiated for the sale of commercial aircraft to Iranian airlines, contracts that became symbolic of the nuclear agreement’s broader potential.

Many American companies took advantage of General License H, which stipulated that non-US subsidiaries of US companies could broadly engage with the Iranian economy. For example, Procter & Gamble, which ran its Iran operation out of its Swiss subsidiary, rapidly re-entered the Iranian market, where it could reliably generate over $100 million in annual revenue. American technology companies took advantage of a similar license called General License D-1 to export digital services to Iranian users.

Finally, American companies were even able to export to directly Iran without relying on a licensing regime if their sales were consistent with longstanding exemptions for humanitarian trade. Medical device companies like GE Healthcare and Baxter enjoyed bumper sales to Iranian hospitals. Pharmaceutical giants like Eli Lilly and Pfizer also increased sales, taking advantage of an opening in financial and logistics channels. American commodities giants like Cargill and Bunge sold wheat, sugar, and soybeans to Iranian buyers, including crops grown on American farms.

In short, American companies were making inroads in Iran as recently as eight years ago. It was President Trump’s unilateral decision to exit the Iran nuclear deal and reimpose secondary sanctions that brought an end to these renewed economic relations, leading to the cancellation of billions of dollars of contracts.

Immediately after Trump’s election, Boeing began to lobby the administration not to withdraw from the JCPOA—something Trump had promised to do on the campaign trail. The planemaker argued that the huge Iran contracts supported “tens of thousands of US jobs” and tried to appeal to Trump’s interest in reviving American industry. The appeals did not work. But it is easy to imagine Trump grasping benefits of a massive Boeing deal at this juncture, given the how darling of American industry has lost its shine. Demand for aircraft in Iran could also help compensate for the impact of Trump’s new China trade war on Boeing. Earlier this week, China banned the purchased of American aircraft, putting hundreds of Boeing orders in doubt.

The JCPOA experience makes clear that there was no prohibition in Iran against doing business with US companies. In fact, relations with the US nosedived after Trump’s abrogation of the nuclear deal, but some direct economic links persisted. Iran offered a lifeline for many American soybean farmers who were hammered during Trump’s first trade war with China. When China retaliated by ending the import of American soybeans, crashing the price, Bunge stepped in, delivering multiple cargoes of American-grown soybeans to Iran, even as Trump brought secondary sanctions back in force.

Clearly, a new nuclear deal could rekindle US-Iran economic relations. But the rebound in trade and investment will likely be modest unless there is a concerted effort by both the American and Iranian governments to make deeper economic relations a cornerstone of a new deal—especially if primary sanctions remain in force. Most American firms will be wary about entering the Iranian market given the inherent concerns that any deal between the two countries could break down, leading Trump to reimpose sanctions once again. Companies are also increasingly risk averse in the face of a volatile global economy. Leaving it to the private sector to singlehandedly realize the economic opportunities of the nuclear deal, the strategy taken back in 2016, is unlikely to work. Bilateral trade may rise from its low base, but investment will not materialize given risk perceptions, meaning there will be little in the way of shared incentives to bind the US and Iran together. A more structured plan for cooperation is needed.

Iranian negotiators are seeking structured cooperation, although their vision remains somewhat ill-defined. Reprising a demand from the talks that were undertaken with the Biden administration, Iranian negotiators continue to target some form of “guarantees” that would ensure the US cannot easily and costlessly withdraw from the nuclear deal while Iran remains in compliance with its obligations. Political and legal guarantees will have little weight. But deeper US-Iran economic cooperation can act as a kind of “technical guarantee” that serves to increase the credibility of the long-term commitments enshrined in any new nuclear deal.

Trump’s turn towards a decidedly “America First” economic policy might actually help Iran as it tries to find a win-win formula for economic cooperation that goes beyond increased purchases of American consumer goods, pharmaceutical products, and agricultural commodities. As economist Djavad Salehi-Isfahani has recently detailed in a review of investment data, Iran desperately needs to renew its capital stock and reverse a decade of technological regression. Meanwhile, the US is trying to rekindle domestic manufacturing of capital goods. The interests align nicely.

The economic commitments related to any new US-Iran nuclear deal should be structured to enable Iranian industrial giants to make major purchases of American-made capital goods—machinery, equipment, aircraft, and vehicles.

Iran’s capital stock is primarily European and was installed around 20 years ago, when European firms were making major investments in the country. But a significant portion of this machinery remains American in origin or design—a reflection of the fact that large parts of Iran’s industrial sectors have not been updated since the 1970s. Many turbines spinning in Iranian power plants and diesel locomotives chugging on Iranian rails are based on GE designs. Many drill heads used to bore oil wells are derivatives of Schlumberger designs—the Texas company’s former Iran subsidiary lives on. Another former American subsidiary, Iran Combine Manufacturing Company, was once called “Iran John Deere.” The company continues to produce trademark green and yellow tractors and combine harvesters—using American designs from 50 years ago. American engineers will find familiar technologies in use at Iranian industrial plants. Renovating and upgrading these facilities will be straightforward, especially given the incredible acumen of Iranian industrial engineers and technicians who will be eager partners.

Importantly, a surprisingly small portion of Iran’s capital stock is Chinese. Chinese exports of capital goods to Iran totaled $6 billion in 2023. But this is the same level as achieved in 2017, the last year that Iran enjoyed sanctions relief. Meanwhile, Chinese investment in Iran has languished under sanctions, plateauing since 2014. There are no major Chinese manufacturing investments in the country and Iran has not been able to substitute the loss of its European industrial partners with Chinese partners. That leaves a uniquely large and open market for American exporters—perhaps the last major economy in the world where the US could reasonably overtake China as an industrial partner.

Given the aligned interests of their respective industrial policies, the US and Iran should think ambitiously about the scope of their economic relations. Iranian firms will be eager customers for new machinery and equipment. Crucially, this kind of trade does not make Iran dependent on the US. Rather, it restores the strength and resilience of the Iranian industrial sector. Once capital goods are installed, they can last for decades—a kind of guarantee that the benefits of a US-Iran deal will last.

Finally, Iranian purchases of American equipment must be financed by American banks. This will make it more likely that the financial logjams associated with JCPOA sanctions relief will be solved. If US banks do business with Iran on Trump’s instructions, global banks will follow. Notably, Trump’s efforts to revitalize the Export-Import Bank could give American exporters access to crucial export credit, insurance, and guarantees.

Trump loves gold. If he remains pragmatic and focused when it comes to Iran, he could strike gold in several ways. He could forge the kind of nuclear deal Thomas Pickering once called the “gold standard for non-proliferation agreements,” once again subjecting Iran to the strictest IAEA verification regime ever devised. He could earn billions in export revenue for the US—and given the US is unlikely to import much Iranian oil—generate a rare trade surplus with a country that is poised to return to its position as one of the twenty largest economies in the world. Finally, if Trump is ambitious and if Iran’s leaders are courageous, he could finally earn the gold medal he has always wanted—a Nobel Prize.

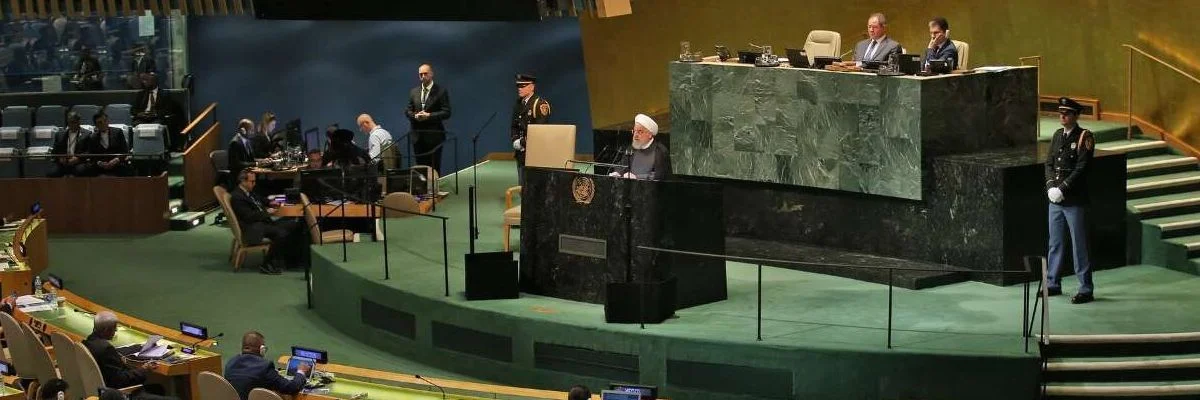

Photo: The White House

Iran Trade Mechanism INSTEX is Shutting Down

At the end of January, the board of Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX) took the decision to liquidate the company.

At the end of January, the board of the Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX) took the decision to liquidate the company. Established in January 2019 by the United Kingdom, France, and Germany, INSTEX’s shareholders later came to include the governments of Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands, Finland, Spain, Sweden, and Norway.

The state-owned company had a unique mission. It was created in response to the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal in May 2018. European officials understood that the reimposition of US sanctions would impede European trade with Iran. The nuclear deal was a straightforward bargain. Iran had agreed to limits on its civilian nuclear programme in exchange for the economic benefits of sanctions relief. If European firms were unwilling or unable to trade with Iran, that basic quid-pro-quo would be undermined. For this reason, supporting trade with Iran was seen as a national security priority.

In August 2018, EU high representative Federica Mogherini and foreign ministers Jean-Yves Le Drian of France, Heiko Maas of Germany, and Jeremy Hunt of the United Kingdom, issued a joint statement in which they committed to preserve “effective financial channels with Iran, and the continuation of Iran’s export of oil and gas” in the face of the returning US sanctions. They pointed to a “European initiative to establish a special purpose vehicle” that would “enable continued sanctions lifting to reach Iran and allow for European exporters and importers to pursue legitimate trade.”

In November 2018, when the basic parameters of a special purpose vehicle were still being formulated by European officials, I co-authored the first public white paper explaining why establishing such a company made sense. Conversations with European and Iranian bankers and executives had made clear to me that trade intermediation methods were being widely used to get around the lack of adequate financial channels between Europe and Iran. If these methods could be packaged as a service by an entity backed by European governments, it would reassure European companies about remaining engaged in the Iranian market, while also reducing costs.

A few months later, INSTEX was founded. In the beginning, the company was run by the Iran desks at the EU and E3 foreign ministries. The officials tasked with working on INSTEX, who were often very junior, quickly realised they had little knowledge of the mechanics of EU-Iran trade. When they sought to enlist help from colleagues at finance ministries and central banks, they frequently met resistance. Many European technocrats were reluctant to support a project which had the overt aim of blunting US sanctions power, even at a time when figures such as French finance minister Bruno Le Maire and Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte were making bold statements about the need for European economic sovereignty. Even INSTEX’s inaugural managing director, Per Fischer, departed given concerns over his association with a company that had been maligned by American officials as a sanctions busting scheme. Then, in May 2019, when the Trump administration cancelled a set of sanctions waivers, European purchases of Iranian oil ended. That left INSTEX as Europe’s only gambit to preserve at least some of the economic benefits of the nuclear deal for Iran.

Later that year, INSTEX hired its first real team after a new group of European governments joined as shareholders and injected new capital into the company. For a time, things looked more promising. Under the newly appointed president, former German diplomat Michael Bock, a small group of talented individuals worked to define INSTEX’s mission and build a commercial case for the company’s operation. Their efforts led to INSTEX’s first transaction, which was completed in March 2020—the sale of around EUR 500,000 worth of blood treatment medication. The political pressure to provide Iran some gesture of tangible support during the pandemic had also greased the wheels in European governments.

But many considered the INSTEX project doomed even before the first transaction was completed. Certainly, Iranian officials were derisive of the special purpose vehicle. Given that Europe had failed to sustain its imports of Iranian oil and was unable to use INSTEX for that purpose, focusing instead on humanitarian trade, Iranian officials dismissed the effort, even after the feasibility of the special purpose vehicle was proven. That it took more than a year to process the first transaction also meant that the Europeans missed their chance to fill the vacuum caused by the US withdrawal from the nuclear agreement. Without full cooperation from its Iranian counterpart, which was called the Special Trade and Finance Instrument (STFI), INSTEX could not reliably net the monies owed by European importers to Iranian exporters with those owed by Iranian exporters to European importers.

European officials will no doubt blame Iran for the fact that INSTEX failed, and it is true that the Iranian government never fully appreciated the political significance of European states taking concrete steps to counteract even the indirect effects of US sanctions. Of course, the decision to liquidate the company follows a spate of recent actions by the Iranian government—nuclear escalation, the sale of drones to Russia, and the brutal repression of protests—that make the continued operation of INSTEX politically untenable.

But most of the blame for INSTEX’s failure must lie with the Europeans—the company’s demise predates Iran’s recent transgressions. European officials promised a historic project to assert their economic sovereignty, but they never really committed to that undertaking. A mechanism intended to support billions of dollars in bilateral trade was provided paltry investment. European governments never figured out how to give INSTEX access to the euro liquidity needed to account for the fact that Europe runs a major trade surplus with Iran when oil sales are zeroed out. For the Iranians, this alone was the evidence that European leaders saw INSTEX as a political gesture that might placate Tehran, rather than an economic instrument that would bolster Iran’s economy in the face of Trump’s “maximum pressure.”

Paradoxically, Iran will lose nothing as the liquidators shut down INSTEX, quietly selling the few assets the company had accumulated—laptops, office chairs, and perhaps some nifty pens. It is Europe that is losing out. INSTEX was supposed to be a testbed for new ways of facilitating trade without relying on risk-averse banks to process cross border transactions. Successful innovation in this area would have given a new dimension to European economic diplomacy and helped Europe assert the power of the euro in global trade.

With the writing on wall, INSTEX’s management made one final attempt to give the company a future. Beginning in 2021, the company pursued a French banking license—a pivot that INSTEX’s board had approved on a provisional basis, but which was halted in early 2022. It is hard to overstate how significant it would have been had INSTEX emerged as a state-owned bank with a specific mandate to process payments on behalf of European companies that wish to work in high-risk jurisdictions, including those under broad US sanctions programme. Such a bank could have become a powerful tool for Europe to assert its economic might in the face of US sanctions. Moreover, it would even have been useful in cases where Europe is applying sanctions, like Russia. After all, a commitment to humanitarianism means that goods such as food and medicine must continue to be bought and sold even when most transactions with a given country are prohibited. INSTEX could have helped make European sanctions powers more targeted and more humane.

For a company that managed just one transaction, a surprising amount has been written about INSTEX. It has been the subject of news reports, think pieces, and academic articles. Even if many people struggled to understand what the special purpose vehicle aimed to do, its existence was novel and therefore noteworthy. For those insiders directly involved in the company’s saga, and for those of us who have closely followed from the outside, the main takeaway seems to be that there is much yet to be learned about the complex ways in which US sanctions impact European policy towards countries like Iran, through both political and economic vectors. In this respect, INSTEX did achieve something. A group of technocrats in European foreign ministries and finance ministries learned valuable lessons, often reluctantly and with great difficulty, about the limits of Europe’s economic sovereignty. Whether those lessons can be institutionalised remains to be seen. But a fuller post-mortem on INSTEX would no doubt offer important lessons for the future of European economic power in a world dominated by US sanctions. Learning those lessons would be its own special purpose.

Photo: Wikicommons

The Plan to Save the Iran Deal Needs Private-Sector Buy-In

Iran will expect economic benefits as part of any mutual return to compliance with the nuclear deal. If Washington and Europe hope to offer a meaningful economic incentive, engaging with the private sector and managing Tehran’s expectations will be key.

With the election of Joe Biden to the US presidency dialogue, between Washington and Tehran appears to once again be possible. Both Tehran and the Biden team have expressed a willingness to consider a “clean” return to the terms of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA, better known as the Iran nuclear agreement) if the other does the same. Namely – Iran would revert its nuclear activities to within the limits set out in the JCPOA, which it began breaching in May 2019, and the US would once again lift sanctions on Iran as prescribed by the agreement.

Reality, of course, will be more complicated. Securing economic benefits will be a priority for Tehran in any dialogue on the future of the deal, or any agreement that may succeed it. However, as became clear following the initial removal of US and international sanctions on Iran in 2016, the degree to which sanctions-lifting on paper translates to economic relief in practice depends in no small part on the willingness of the private sector to engage with the Iranian market. If the US and E3 hope to present renewed trade and investment as a credible and meaningful incentive for Iranian cooperation, it will be necessary to both address private sector concerns and manage Iranian expectations.

At the moment, many businesses around the world have opted out of engaging with Iran. The scope and complexity of US economic measures against Iran, as well as the high costs of potentially losing access to the US market and financial system in case of an accidental breach, is sufficient to turn even the most well-resourced compliance departments off of engaging with Iran. Iran is also one of only two countries—alongside North Korea—on the “blacklist” put forth by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), the global standard-setter on countering financial crime. As a result of Iran’s failure to address “strategic deficiencies” in its financial crime regime the FATF currently requires jurisdictions to apply “enhanced due diligence” to their transactions with Iran, leading many banks to opt out of transacting with the country altogether. This means that businesses struggle to access financial infrastructure necessary for doing business with Iran.

There is some indication that, even if US sanctions on Iran were lifted, the uptake for private sector engagement with Iran would remain slow and limited. A few weeks ago, Iranian president Hassan Rouhani reportedly requested that Iran’s Expediency Council reprise its review of legislation that would address the deficiencies in Iran’s financial crime legislation called out by the FATF, which may help address some private sector concerns. However, persistent challenges in relations between Iran and the US and E3 will continue to create uncertainty for businesses. On December 17, the European Parliament passed a resolution condemning Iran’s detention and execution of human rights defenders and prisoners of conscience and called for the application of targeted financial sanctions on the Iranian individuals responsible. A few days earlier, a European Union-funded virtual business conference was postponed following the execution in Iran of journalist Rouhollah Zam.

Furthermore, some key US economic measures against Iran—for instance, sanctions on the Central Bank of Iran and on the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), as well as the designation of Iran as a jurisdiction of primary money laundering concern—are not related to Iran’s nuclear activities and may not be lifted as part of a return to the nuclear deal. These sanctions will continue to create complexity for banks and other businesses and will factor into private sector risk calculus. The possibility of another snap-back of US nuclear-related and secondary sanctions on Iran under a future change of administration in Washington will also discourage businesses investment. Persistent concerns over exposure to US sanctions within the financial sector in particular will complicate renewed economic engagement with Iran, as businesses will have trouble finding banks willing to support financial transactions with Iranian counterparts. Efforts by the incoming Biden administration to figure out the legal and regulatory logistics of sanctions-lifting, while ensuring that sanctions remain an effective tool of US foreign policy, will therefore also have to address challenges in the practical implementation of sanctions-relief.

Reversing the economic impacts of private sector reticence to engage with Iran will be top of mind for the Islamic Republic as it engages with the new Biden administration. Tehran has previously called for compensation for “damages” to the Iranian economy caused by US sanctions – although Iranian leadership appears to have dropped such demands as a pre-condition for an Iranian return to compliance with the JCPOA in recent statements. And while Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei expressed support for seeking sanctions-removal in recent marks directed at Iranian officials and the Iranian public, he also stressed the importance of “nullifying” the impact of sanctions on the Iranian economy. He distinguished “neutralizing” sanctions from sanctions-lifting and seemed to express scepticism over US and European ability to deliver on the former.

Assessing business’ levels of interest in re-engaging with the Iranian market and addressing concerns where possible will lend greater weight to US and European incentives of economic relief, hopefully encouraging greater cooperation from Iran in any future diplomacy—whether on its nuclear programme or more broadly. Relaying to Tehran the results of these private sector consultations may also help manage Iranian expectations on the level of foreign economic interest it can expect following sanctions lifting while also stressing the need for Iran to get its financial regime in order. On the part of Washington, this may include preparing comfort letters, granting sanctions exemptions, updating general licenses and expanding the guidance issued via the Office for Foreign Assets Control “Frequently Asked Questions” on Iran sanctions.

By consulting with their private sectors, the European governments can also better-understand business concerns and uncertainties around engagement with the Iranian market and how these may shift—or fail to do so—with the lifting of US sanctions. In October 2020, the European Commission launched a “Due Diligence Help Desk” aimed at supporting European companies in navigating European sanctions on Iran. While the platforms are well-intentioned and may provide businesses with helpful guidance, it is unclear how effective they will be in practice. The platforms do not address some of the key challenges raised earlier, including the lack of financial infrastructure to support transactions with Iran and concerns over exposure to US sanctions. The UK and European governments may wish to identify and reach out to specific sectors that are likely to be of greatest importance to renewed trade with Iran—for instance, the banking sector or those engaged in energy trade—to ensure they have the assurances, guidance, and infrastructure they need to proceed with confidence. Coordinated efforts across capitals—for instance, through the issuing of joint guidance by American, British, and European financial regulators, as well as dialogue with the US on the concerns of UK and European businesses—will also be valuable.

As renewed diplomacy on the Iranian nuclear question gets underway, it will have to be supplemented by consultations with businesses to assess whether the private sector will be able to make good on economic promises made at the negotiating table, as well as to manage Iranian expectations. At the same time, understanding and, where possible, addressing private sector concerns will help businesses do what they do best—moving goods, people, and capital to ensure that the lifting of sanctions on paper translates into real economic uplift for Iran.

Photo: IRNA

How Biden Can Stop Iran’s Conservatives From Undermining the Nuclear Deal

Insisting that Iran must abandon its missile program could see Joe Biden fall into the hardliners’ trap and make a new agreement impossible.

By Saheb Sadeghi

U.S. President-elect Joe Biden has so far spoken sparingly on Iran, including an op-ed on the CNN website and in an interview with the New York Times. As part of a step-by-step strategy, he has said that he would return to the nuclear deal as the first step and then address other concerns about Iran’s regional influence and missile capabilities. But how will the Iranian government react to the United States’ demand that the regional issues and the missile capabilities should be part of the negotiation?

There are two different approaches in Iran to handling comprehensive negotiations with the United States.

There is broad consensus within the Iranian establishment that Iran will not make any concessions regarding its deterrence and defense strategy.

Iran has traditionally used a deterrent strategy to strengthen its national security and defend its territorial integrity in recent years. This strategy has two prongs. The first is strengthening and supporting regional allies and militant movements in Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and elsewhere; the second is enhancing its missile capabilities and building and testing short- and long-range missiles, as well as ballistic missiles.

This strategy has expanded since the U.S.-led wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, which brought hundreds of thousands of U.S. troops into the region just a few miles from Iran’s eastern and western borders, dramatically increasing the risk of an imminent military strike on Iranian territory. Tehran has pointed to security threats in its vicinity and the fact that it is not a member of any regional military coalitions as the reasons it needs to develop missile capabilities and expand its influence in the Islamic countries in the Middle Eastern region.

Despite this general consensus on deterrence strategy, the Iranian government’s approach to Biden’s call for comprehensive negotiations can be divided into two camps.

The first group is made up of conservatives, who recently gained an absolute majority earlier this year in parliamentary elections and are expected to win the next presidential election. The conservatives strongly reject any talks with the United States on non-nuclear issues and their position has been further strengthened by the assassinations of the commander Gen. Qassem Suleimani in early 2020 and more recently the prominent nuclear scientist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh.

In their view, these assassinations were an attempt by Iran’s enemies to paralyze Iran’s deterrence, and now is the time to revive this deterrence, rather than negotiate. Reflecting this view, Saeed Jalili, a senior member of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council (SNSC) and the former nuclear negotiator during the presidency of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, harshly criticized President Hassan Rouhani for discussing the missile issue with French President Emmanuel Macron in a telephone conversation. (He called for the refusal of such talks on the part of Rouhani, declaring that non-nuclear talks are prohibited and unacceptable.)

Conservatives believe that just as the West sought to limit Iran’s nuclear capabilities in past nuclear talks with the country, any negotiations on missile and regional issues would inflict a crushing blow to Iran’s national security. The hardline speaker of the parliament, Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf, recently said, “Negotiations with the United States are absolutely harmful and forbidden.” During Ahmadinejad’s presidency, when conservatives were in power, the world witnessed six years of fruitless negotiations between Iran and the West from 2008 to 2014, and this trend could repeat itself if the conservatives win the next presidential election.

The other group is made up of pragmatists and moderates who, despite emphasizing the need to strengthen Iran’s deterrence strategy, do not see non-nuclear negotiations as a threat to Iran’s national interests. Even so, they will not accept that the implementation of the nuclear agreement should be conditional on regional and missile negotiations.

In their view, if Biden’s foreign policy team focuses on the alleged need for so-called Middle East security and arms control talks instead of insisting on countering Iran’s regional influence and the need for limiting and disarming its missiles, it will be possible to reach an agreement between Iran and the West with the cooperation of countries in the region.

To them, when “countering Iran’s regional influence and its missiles,” is on the U.S. agenda, it means an aggressive approach toward Iran that does not consider the country’s legitimate security concerns. Such an approach will not be effective as the Iranians have shown with their resilience in the face of unprecedented U.S. sanctions, resulting from outgoing President Donald Trump’s maximum-pressure campaign.

The pragmatists believe that Iran’s missile policy is entirely defensive and deterrent in nature; Tehran has already stated that its missiles’ range will not exceed 2,000 kilometers (1,240 miles) while some Arab states in the region such Saudi Arabia have purchased missiles with a range of 5,000 kilometers (3,100 miles).

The pragmatists believe that in potential future region-wide negotiations, if pressure is put on Iran to limit its missile capabilities, Iran could rightfully bring up the issues of Saudi Arabia’s missiles, Israel’s nuclear warheads, and modern arms purchases by the Persian Gulf states as a justification for its insistence on keeping its own missile capabilities. The purchase of F-35 fighter jets by the UAE and Israeli nuclear weapons could be on the agenda of the possible future talks, which will give Iran the upper hand in those negotiations.

In such a situation, the United States and regional actors must decide whether to move toward a broader arms-control process in the Middle East or to recognize Iran’s right to have a missile capability. The pragmatists think that there should not be any fear of negotiation; instead, they argue that the opportunity of negotiations should be used to consolidate Iran’s regional and defense achievements. They see Biden’s victory as an opportunity to resolve Iran’s regional and international problems and see his approach to solving the Middle East’s problems as balanced in contrast to Trump’s.

This pragmatists’ view is even more relevant given Biden’s talk about reconsidering the U.S. position on Saudi Arabia. During his presidential campaign, he vowed to reassess the U.S. relationship with the Saudis and put an end to U.S. support for Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen.

The pragmatists argue that former President Barack Obama was moving in that direction, and now Biden could step into Obama’s shoes and continue along that unfinished path. In an interview with the Atlantic in May 2015, Obama emphasized that an approach that rewards Arab allies while presenting Iran as the source of all regional problems would mean continuing sectarian strife in the region. Obama stressed that Saudi Arabia had to learn to share the Middle East region with its sworn enemy, Iran.

Biden’s pick for national security advisor, Jake Sullivan, said in a lengthy interview with The Center for Strategic and International Studies that the Biden administration will stop Trump’s maximum pressure campaign against Iran and would not hold the nuclear deal hostage for regional and missile talks, but by returning to deal it would put pressure on regional actors—including Iran and Saudi Arabia—to undertake regional talks. He also said that the United States will hand over these negotiations to regional countries and will not take the lead. Such a position aligns with Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif’s recent statement reiterating Iran’s readiness to hold talks with countries in the region on security and stability in the Middle East.

Even China’s foreign minister has recently called for Middle East security talks. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov recently reiterated Putin’s proposal for talks between the U.N. Security Council permanent members and Iran to establish a collective security order in the Persian Gulf.

Iran’s readiness to use the influence it enjoys over the Houthis to end the Yemeni war—which Biden has insisted on and which lies at the core of Saudi Arabia’s national interests and security—seems to be a golden starting point. Iran can persuade its Yemeni allies to sign a peace agreement with Saudi Arabia.

However, there are serious barriers to regional and missile negotiations, the resolution of which will depend on the approach of the Biden foreign policy team. The atmosphere of mistrust between Iran and the United States, influenced by Trump’s maximum-pressure campaign and the assassinations of Suleimani and Fakhrizadeh, is the primary obstacle.

The second obstacle is the short period that Rouhani is still in office. With Biden taking office on Jan. 20, 2021, the two countries have only five months before Iran’s upcoming presidential election to revive the nuclear deal and work on other issues.

If the Biden administration’s plans to revive the JCPOA and lift sanctions do not go ahead as predicted, the two sides will be in serious trouble in early February, when the deadline included in a bill pushed by hardliners as an intentional spoiler and recently passed in the Iranian parliament expires.

Iran’s parliament has given European countries and the United States two months to lift sanctions. The Rouhani administration has expressed its opposition to the bill, describing it harmful to diplomatic efforts. However, because it has become law, they cannot prevent it from being enforced. Zarif has said the government will be forced to implement the law, according to which Iran will abandon almost all its nuclear obligations.

If such a law is implemented, it is possible that the JCPOA—which has survived four years of Trump administration’s immense pressure—would die in the first month of Biden’s presidency. Biden could lift the sanctions that were suspended by the nuclear deal with several executive orders, and then, as Rouhani recently announced, Iran will return to its nuclear obligations.

Saheb Sadeghi is a columnist and foreign-policy analyst on Iran and the Middle East. Follow him at @sahebsadeghi.

Photo: Wikicommons

Iran Archaeology is Awaiting a Sanctions Breakthrough

While a considerable number of Iranian heritage professionals are still working on international collaborations, the shifting winds of both global and Iranian domestic politics have made archaeological fieldwork in Iran a complicated and risky endeavor.

This article is the fourth in a five-part series.

Read Part 1 here

Read Part 2 here

Read Part 3 here

Cooperation in the field of archaeology between Iranian and foreign researchers has a long history. In my academic research, I am currently combing the archives associated with all the major American archaeological expeditions to Iran, beginning in 1930 and continuing until 1978, focusing on the activities of the University of Pennsylvania Museum, the Oriental Institute, the Field Museum, the Boston Fine Arts Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University, among others. This record shows intensive contacts between heritage professionals of both nations over a sustained interval in contexts such as field research, museum exhibits, student exchanges, and UNESCO initiatives. As positive as these relations may have been for those who participated in them, heritage collaborations were marked by the same steep power imbalances that characterized the overall midcentury relationship between the United States and Iran.

In the early days of international collaboration in archaeology, Iranian researchers often participated only as trainees. Iranian leadership in archaeological projects was largely on Iranian projects, in which few foreigners participated. In recent years, this has changed. Since around 2000, all foreign archaeological projects in Iran have been joint endeavors; under current regulations, all cooperative research must be staffed by workers and researchers that are at least at numerical parity. The past two decades have seen major restoration projects at the citadel of Bam (an Italian collaboration), surveys and excavations in the Tehran Plain (British) and in the Mamasani district of Fars Province (Australian, British, and American), continued work at Persepolis and Pasargadae (multi-national, but especially French, German, and Australian), as well as excavations at Konar Sandal (American), and at numerous sites in northeastern Iran (German and Chinese), to name just a few examples. Indeed, one of my sources commented that the period from 2003 to 2016 was a high point for foreign archaeology in Iran.

Since 2017, conditions for foreign involvement in archaeological research in Iran have been less than favorable. However, the work continues. To get a sense of the effect of American policy in shaping archaeological fieldwork in Iran, and specifically joint international collaborative projects, I consulted colleagues and experts from a range of professional and national backgrounds. Given the sensitivity of the topic, all interviews were conducted on background. Most of my sources had worked in Iran as recently as 2018, but several had not been able to travel to Iran since 2014, or even as long ago as 2011. The consensus among these individuals is that conditions have worsened considerably in recent years, taking a particularly bad turn with the Trump administration’s executive orders known as the “Travel Ban,” maximum pressure, and the reimposition of broad-spectrum sanctions in 2018 following the US exit from the JCPOA.

***

During the early years of the Rouhani administration, before and immediately after the JCPOA rapprochement, conditions for archaeological research were seen to be improving. Nevertheless, all of my sources recognized that even in the best of times, the internal political situation in Iran complicates the regular functioning of archaeological research. I heard again and again that while procedures and protocols sometimes move along in a smooth and timely fashion, as often as not, there can be long delays in receiving permits and visas with little warning or explanation. While a considerable contingent of Iranian heritage professionals actively seeks to promote international collaborations, the shifting winds of both global and Iranian domestic politics can have drastic effects on the possibilities for cooperative research. These conditions are understood to make the conduct of archaeology in Iran a highly risky endeavor for foreign missions.

For example, one researcher I spoke with worked in Iran as recently as January 2020. After a lengthy wait, their visas and permits finally came through in late autumn 2019. Due to the rising tensions and skirmishes in the Persian Gulf, the leader of this team felt obliged to devise an escape plan and carry extra cash, charting routes to the nearest international airport, or failing that, the nearest land border through which they could escape in the event of the outbreak of conflict. The assassination of Qassem Soleimani on the 3rd of January 2020, while they were actively excavating, ultimately did not force the research team to flee, but it did show just how necessary such contingency plans had become.

My sources told me that every year it is a struggle to know exactly when one will be able to go to the field, which makes it difficult to plan work and coordinate the participation of specialists. All of the experts I spoke with expressed concern about health, safety, and professional prospects. The consensus seems to be that junior scholars in the West ought not to try to work in Iran until they have a stable position from which they can ride out the ups and downs of intermittent and unstable conditions of access to the field. Several sources related to me that every time they leave Iran after a fieldwork season, they worry that it might be for the last time.

***

Geopolitically speaking, experts agree that archaeology and heritage constitute one of the last remaining channels of good relations between Iran and the West. This has naturally made the field a political football, with foreign specialists in Iranian heritage caught in the crossfire. American archaeologists of Iran have been the most affected. European researchers have had an easier time, but invitations and the processing and issuance of visas are frequently held up by the Iranian Ministry of Foreign Affairs as retribution for unrelated international disputes. Moreover, Iran’s detainment of dual nationals on charges of espionage in recent years, including in some extreme cases lengthy prison sentences and the threat of the death penalty for field researchers, has caused considerable concern on the part of researchers who hold two passports, especially if their documents are American and/or Iranian.

More directly, American sanctions make funding archaeological research particularly difficult. Archaeology is an expensive and logistically complex endeavor everywhere in the world. Research teams typically involve anywhere from three to twenty scholars and students, and a pricey suite of digital recording instruments, including total stations, GPS devices, photography equipment, laser scanners, geophysical instruments, drones, which naturally arouse suspicion due to their perceived potential for dual use—in addition to the usual trowels, picks, shovels, dustpans, brushes, buckets, and wheelbarrows.

The particular complication in the case of foreign missions in Iran is that it is not possible to conduct bank transfers between international and Iranian banks and international credit cards cannot be used. Therefore, foreign researchers are obliged to carry cash —in some cases amounts approaching EUR 50,000—and exchange it for rials in order to conduct their business. This—in addition to general complications with bank-transfers due to secondary sanctions—is a logistical nightmare for the researchers on the ground, but also a significant concern for funding agencies and university finance departments.

American sanctions extend beyond purely financial matters as well, particularly with respect to the prohibition on the exchange of services. Several experts specifically highlighted issues with the export of scientific samples for analyses that cannot be performed in Iran. After negotiating the already challenging internal bureaucratic regulations governing the shipment of scientific samples within Iran, it is then extraordinarily difficult to transport them safely or predictably to Europe or North America. This can mean, in some cases, years-long delays, which cause particular problems for foreign researchers insofar as their employment or professional advancement may depend on the results of such analyses, not to mention the frustrations of Iranian specialists eager to participate in the international scientific community. American sanctions also prevent the use of basic and routinely-used software packages such as ArcGIS Online, which researchers may be obliged to run through university contracts with the provider of the software, ESRI. This service cannot be accessed in Iran, meaning that a crucial tool in archaeological research is unavailable for both foreign and Iranian researchers.

As it turns out, many of these complications are not due to the actual OFAC regulations themselves, which, strictly speaking, do authorize the use of software, the exchange of services, and even some limited transactions as part of routine academic research. But university lawyers are extraordinarily skittish about permitting and funding fieldwork in Iran, afraid of being sued by the US Treasury. In some cases, these concerns can be allayed through obtaining a specific license to authorize a circumscribed program of research. Due to the complicated, lengthy, and expensive process involved in obtaining such a license, however, in practice this means that it is almost impossible for American citizens to be involved in Iranian projects. This appears to be particularly true of the past five years, when licensing has been much more restricted, and the Trump administration has moved to take power out of the hands of the OFAC bureaucracy.

OFAC licensing was one of the major sticking points in the Persepolis Tablet Archive Return project, mentioned in the previous article. I learned that the process of obtaining the license took almost a year and required extensive documentation of every object being transferred and the particulars of the itinerary of the participants in Tehran. OI representatives felt the need to go so far as to print out English-language exhibit labels in Chicago, rather than run the risk of violating sanctions protocols by printing them in Tehran. Such are the absurdities of the situation. Moreover, the Oriental Institute was advised not to do a press junket in the US, to avoid drawing unwanted attention to the work from powerful Iran-hawks in the federal government that might complicate future OFAC licensing.

Simultaneously, the American policy of maximum pressure is squeezing the Iranian economy as a whole. In practical terms, for Iranian archaeologists, this means that access to equipment and the international scientific community is made all the more difficult. Necessary electronics are far more expensive in Iran, visas and funding for participation in international conferences are difficult to obtain, many artifact conservation supplies are scarce and exorbitantly priced, and certain kinds of routine analysis cannot be performed in Iran. Additionally, as discussed previously, due to the funding structure of the MCHT, there is plenty of money for the conservation of monuments and the promotion of tourism, but very little funding for primary archaeological research. Most of the scientific excavation that occurs is salvage or rescue work, which must occur on an accelerated timeline in order to recover archaeological remains in advance of construction and infrastructure projects. Given these conditions, one of the only avenues to obtain funding for academic archaeological field research is to join with a foreign collaborator who might be able to bring with them funding from abroad.

***

Despite all of these difficulties, the expert consensus is that there is huge potential for international scientific collaboration between Iranian and foreign researchers. Those that I spoke to were unanimous in their recognition of the high degree of professionalism among archaeological researchers in Iran, and the quality of their fieldwork. Foreign archaeologists see their Iranian colleagues as partners on an equal footing scientifically, and indeed, many Iranian archaeologists in leadership positions within MCHT, the Iranian Center for Archaeological Research, and in academic departments, have PhDs from the very same universities in France, Germany, the UK, the US, and Canada. Iranian archaeologists are perceived as particularly open to innovation, especially in the use of advanced technologies in archaeological fieldwork, and in archaeometric and laboratory analyses such as geophysics, petrography, metallography, paleoecology, photogrammetry, and radiography, among others. The general view is that the level of scientific work in Iranian archaeology is quite high by global standards, and all that I spoke to felt compelled to relate to me their great sense of privilege when given the opportunity to work in Iran.

The present political situation has forced many foreign archaeologists of Iran to continue their research and publishing collaborations remotely. For some, particularly American and British researchers, this was already the reality for some time. With all of the difficulties in obtaining visas and securing funding to continue cooperative fieldwork in Iran, many of my colleagues have had to come up with creative solutions to keep their work going. In some cases, this takes the form of an active social media presence and online exchanges. In others, it involves remote mentorship of students by virtual means, training them in research methods and guiding their work in data collection and analysis, ideally leading to joint publications and thereby visibility in the international scientific community for those who otherwise would not have access to it.

The question of access is central. To the extent that certain foreign nationals have difficulty accessing the field in Iran, so too do Iranian researchers have difficulty accessing collections of Iranian antiquities stored in Western museums. Several researchers I spoke to expressed strongly that—given the volume of materials stored in institutions such as the British Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, the Oriental Institute, the Louvre, and others—Western researchers have a duty to work with these materials and to make them more accessible. Other ideas that were floated include joint projects conducted remotely, in which projects are designed and published collaboratively, with the fieldwork carried out by Iranians on the ground, and the data and analysis shared over the internet. This of course is not an unproblematic proposal, as global power imbalances would still be at play, and there is a legitimate question as to the extent to which this constitutes a sanctionable exchange of services. My reading of the terms of The US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control General License G suggests that such work is authorized, but circumspection is strongly advised.

***

Regardless of all the difficulties, my sources pointed to several bright spots. To pick just one, the Persepolis Fortification Tablet Archive Return is seen as a model endeavor, and a prime example of how to both keep open and reinforce channels of communication between specialists and stakeholders, both Iranian and foreign. As one of my sources noted, the legal case that opened the door to the 2019 return—Rubin v. Islamic Republic—represents an odd confluence of forces, in which the United States government, the Islamic Republic, and an American institution were all on the same side. How often has this been the case in the general course of the relationship between our two countries over the past four decades? As I have documented in my historical research, despite the poor condition of our bilateral relations today, archaeology and cultural heritage were once seen by US State Department officials as among the best channels for establishing positive ties between the United States in Iran. My hope is that they may someday be so again.

Click here to read Part 5 of this five-part series.

Photo: Wikicommons

Europe Can Preserve the Iran Nuclear Deal Until November

After a humiliating defeat at the U.N. Security Council, Washington will seek snapback sanctions to sabotage what’s left of the nuclear deal. Britain, France, and Germany can still keep it alive until after the U.S. election.

By Ellie Geranmayeh and Elisa Catalano Ewers

The United States just lost the showdown at the United Nations Security Council over extending the terms of the arms embargo against Iran. The U.S. government was left embarrassingly isolated, winning just one other vote for its proposed resolution (from the Dominican Republic), while Russia and China voted against and 11 other nations abstained.

But the Trump administration is not deterred: In response to the vote, President Donald Trump threatened that “we’ll be doing a snapback”—a reference to reimposing sanctions suspended under the 2015 nuclear deal from which the United States withdrew in 2018.

The dance around the arms embargo has always been a prelude to the bigger goal: burning down the remaining bridges that could lead back to the 2015 deal.

The Trump administration now seeks to snap back international sanctions using a measure built into the very nuclear agreement the Trump White House withdrew from two years ago. This latest gambit by the Trump administration is unsurprisingly contested by other world powers.

On the one hand, Russia and China are making a technical, legal argument against the U.S. move, namely that the United States forfeited its right to impose snapback sanctions once it exited the nuclear deal. This is based on Security Council Resolution 2231 that enshrined the nuclear agreement, which clearly outlines that only a participant state to the nuclear deal can resort to snapback. This is a legal position that even former U.S. National Security Advisor John Bolton—an opponent of the nuclear deal and under whose watch Trump left the agreement—has recently endorsed.

In the end, however, this is more a political fight than a legal one. The political case—which seems to be most favored by European countries—is that the United States lacks the legitimacy to resort to snapback since it is primarily motivated by a desire to sabotage the multilateral agreement after spending the last two years undermining its foundations.

The main actor that will decide the fate of the nuclear deal after snapback sanctions is Iran itself. Iran has already acted in response to the U.S. maximum pressure campaign, from increasing enrichment levels and exceeding other caps placed on its nuclear program, to attacking U.S. forces based in Iraq and threatening to exit the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty.

But the calculations of decision-makers in Tehran will be influenced by the political and practical realities that follow snapback sanctions. And here, the response from the remaining parties to the nuclear deal—France, the United Kingdom, Germany, China, and Russia—will be critical. These countries remain committed to keeping the deal on life support—at least until the U.S. presidential election in November.

Seizing on its failure to extend the arms embargo, the United States now claims it can start the clock on a 30-day notification period, after which U.N. sanctions removed against Iran by the nuclear deal are reinstated. This notification will be timed deliberately to end before October—when the arms embargo is set to expire, and also when Russia takes over presidency of the U.N. Security Council: a time when Washington could face more procedural hurdles.

What is likely to follow snapback is a messy scene at the U.N. in which council members will broadly fall into three groups. First, the United States will seek to build support for its case—primarily through political and economic pressure—so that by the end of the 30-day notice period some U.N. member states agree to implement sanctions. The Trump administration will likely use the threat of U.S. secondary sanctions, as it has done successfully over the last 18 months, if governments don’t move to enforce snapback sanctions.

Even if most governments around the world disagree that the United States has any authority to impose snapback sanctions, some countries may be forced to side with Washington given the threat that the United States could turn its economic pressure against them.

The second group will be led by China and Russia, both of which have already started to push back. Not only will this group refuse to implement the U.N. sanctions that the U.S. government claims should be reimposed, but they likely will throw obstacles into the mix, such as blocking the reinstitution of appropriate U.N. committees that will oversee the implementation of such sanctions. This group may also see it as advantageous to seek a determination by the International Court of Justice on the legal question over the U.S. claim.

The third grouping will be led by the France, Britain, and Germany, who remain united in the belief that the deal should be preserved to the greatest extent possible. In a statement in June, the three governments already emphasized that they would not support unilateral snapback by the United States. But it is unclear if this will translate into active opposition—and their approach will certainly not include the obstructionist moves that Russia and China may make.

This bloc will look to stall decisions to take the steps necessary to implement the U.N. sanctions. This is a delicate undertaking, as European countries are not in the habit of blatantly ignoring the binding framework of some of the U.N.’s directives, and will want to balance their actions against the risk of eroding the security council’s credibility further. But they will also take advantage of whatever procedural avenues are in place to delay full enforcement of the sanctions, buying time to urge Iranian restraint in response to the U.S. moves.

Countries such as India, South Korea, and Japan are likely to favor this approach. These governments may even go so far as to send a significant political signal to Iran and back a joint statement by most of the security council members vowing not to recognize unilateral U.S. snapback sanctions.

As part of this approach, the 27 member states of the European Union could embark on a prolonged consultation process over how and if to implement snapback sanctions. The separate EU-level sanctions targeting Iran’s nuclear program are unlikely to be reimposed so long as Iran takes a measured approach to its nuclear activities.

Reimposing EU sanctions against Iran will entail a series of steps, the first of which requires France, Britain, and Germany, together with the EU High Representative, to make a recommendation to the EU Council. The return of EU sanctions would then require unanimity among member states, a goal which will take time to achieve in a context where Washington is largely viewed as sabotaging the nuclear deal.

In this process, the EU should seek to preserve as much space as possible to salvage the deal and avoid the reimposition of nuclear-focused sanctions against Iran—at least until the outcome of the U.S. election is clear. The U.K., in the run-up to Brexit, may well lean toward a similar position rather than tying itself too closely to an administration in Washington that may be on its way out.

Until now, the remaining parties to the nuclear deal have managed to preserve the deal’s architecture despite its hollowing out. The aim has been to stumble along until the U.S. election to see if a new opening is possible to resuscitate the agreement with a possible Biden administration in January.

While a Trump win could spell the end of the deal and further dim the prospects of diplomacy between the United States and Iran, the two sides could come to a new understanding over Iran’s nuclear program at some point during the second term that is premised on the original deal. Judging by the pace of the Trump administration’s nuclear diplomacy with North Korea, this will be a Herculean process with no certain outcome.

In Tehran, there will be some sort of immediate response to the snapback—most likely involving further expansion of its nuclear activities. However, Iran may decide to extend its strategic patience a few weeks longer until the U.S. election. A legal battle by Russia and China against snapback, combined with non-implementation of U.N. sanctions by a large number of countries and continued hints from the Biden camp that Washington would re-enter the nuclear deal could provide the Rouhani administration with enough face-saving to stall the most extreme responses available to Iran.

But with Iranian elections coming in the first half of 2021, there will be great domestic pressure from more hardline forces to take assertive action, particularly on the nuclear program, to give Iran more leverage in any future talks with Washington.

If Iran takes more extreme steps on its nuclear activities, such as a major increase in its enrichment levels or reducing access to international monitors, it will make it nearly impossible for the Britain and the EU to remain committed to the deal in the short term. There are also factors outside Iranian and U.S. control that could have an impact, such as a potential uptick in Israeli attacks against Iranian nuclear targets.

Over the course of the Trump administration, Europe and Iran have managed to avert the collapse of the nuclear deal. Having come so far, and just 11 weeks away from the U.S. election, they will need to work hard to prevent the total collapse of the agreement. Even if Biden—who has vowed to re-enter the deal if Iran returns to compliance—is elected, the remaining parties will need to continue the hard slog to preserve it until January.

Those opposed to the nuclear deal with Iran may see the last two months of a Trump administration as a window to pursue a scorched-earth policy toward Iran’s nuclear program. That leaves Britain and Europe with the job of holding what remains of the deal together, for as long as they can.

Ellie Geranmayeh is a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. Follow her at @EllieGeranmayeh.

Elisa Catalano Ewers is an adjunct senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security and a former U.S. State Department and National Security Council official.

Photo: IRNA

How Europe Can Help Iran Fight COVID-19

The Iranian healthcare system is reliant on long-standing relations with European suppliers to see it through the COVID-19 crisis. European governments should press the US to strengthen the humanitarian exemptions in its Iran sanctions.

This analysis was originally published by the European Council on Foreign Relations.

Iran became an early epicentre of the COVID-19 outbreak due to its close political and economic relations with China. Yet the Iranian healthcare sector overwhelmingly depends on European medicine and medical devices—products that China has been unable to replace. While the European Union and its member states must prioritize their own fight against the virus, they should also protect this important humanitarian connection with Iran.

The Iranian healthcare system is reliant on long-standing relations with European suppliers to see it through the crisis. If there is a grave breakdown in either this supply chain or Iran’s healthcare sector, it will spell trouble for Europe. Given that Iran continues to be the epicenter of the pandemic in a fragile Middle East, the coronavirus is likely to lead to increased refugee flows (particularly among Afghan communities) to Europe. Despite their conflicting opinions on the leadership in Tehran, Europe’s Iranian diaspora community – who, until recently, often travelled to Iran – broadly agree on the need for enhanced humanitarian assistance to Iran, which could save hundreds of thousands of people.

Following two years of recession linked to systematic mismanagement, falling oil prices, and the unique pressure created by US sanctions, Iran’s government is facing extreme trade-offs between the optimal public healthcare response and the need to prevent a full-blown economic crisis. These sanctions hamper Iran’s immediate response to COVID-19.. Despite their humanitarian exemptions, the measures make the import of medicine and medical equipment – as well as the raw materials needed to produce many of these goods in Iran – both slower and more expensive. This erodes the capacity of the Iranian healthcare system to replenish its inventories as Iran’s outbreak moves into its third month. Moreover, the Iranian government cannot afford the type of economic stimulus packages that governments across the globe have implemented to reduce the impact of lockdowns.

While the US has made general offers to send aid to Iran, leaders in Tehran will perceivethem as disingenuous for so long as the sanctions are in place. Given the sharp downturn in US-Iranian relations under the Trump administration, it is unrealistic to think that either the United States will provide full sanctions relief or that Iran will accept aid from a country it believes to be pursuing regime change in Tehran. Although the more hard-line elements within the Iranian system are suspicious of European assistance (as recently reflected in Iran’s sudden rejection of aid from Médecins Sans Frontières), there is some breathing room for the country to cooperate with Europe on this front.

Building on recent announcements by the EU, France, the United Kingdom, and Germany, European governments should continue to provide financial assistance and other aid to Iran’s public healthcare system and trusted NGO partners working in the country. European companies can also boost humanitarian trade via the Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX) – which has now processed its first transaction, targeting Iran’s core public healthcare needs in the fight against COVID-19..

The European Commission has implemented export controls on key items in the fight against COVID-19, to minimize shortages in Europe. This move puts Iran and other low-income and developing countries at even greater risk, given their significant reliance on European exports. Rather than cut these supply chains, which forces Iran to turn to China and Russia, the EU should explore whether Iran could ramp up its production of basic medical equipment, such as surgical masks, to help meet demand in Europe. This would allow European manufacturers to focus on the production of more advanced items, such as face shields – the surplus of which it could/ sell to Iran.

Most importantly, European governments and the EU should press the US to strengthen the humanitarian exemptions in its sanctions. European leaders should urge the US Treasury to expand and clarify the scope of these exemptions to directly include products Iran needs to combat COVID-19 effectively. Such clarification, which could take the form of a “white list” of goods, should allow European companies to apply General License No. 8, under which the Central Bank of Iran can help facilitate humanitarian trade.

Given the unprecedented humanitarian fallout from the COVID-19 crisis, European governments should also urge the US administration to issue comfort letters to European banks that already conduct enhanced due diligence on trade with Iran. This would help reassure these banks that the US Office of Foreign Assets Control will not penalise them for providing payment channels to exporters of humanitarian goods. The Trump administration recently took the unprecedented step of issuing such a letter to Swiss bank BCP under the Swiss Humanitarian Trade Arrangement. As former US official Richard Newphew has argues, the US could provide similar letters to manufacturers and transport firms, helping reassure companies across the entire medical supply chain that they can facilitate sales to Iran.

While the International Monetary Fund reviews Iran’s $5 billion loan request, European governments should press the Trump administration to temporarily allow Tehran to access Iranian foreign currency reserves. In this, the administration could restore the escrow system that enabled Iran to use its accrued oil revenues to purchase humanitarian goods prior to May 2019. These funds (including those in Europe) could be subject to existing enhanced due diligence requirements and spent within the countries in which they are currently located. The funds in Europe could also be linked to INSTEX.

Such US measure could be connected to humanitarian steps by Iran, not least the release of American detainees. In particular, France and the UK – some of whose nationals Tehran has released from prison (either permanently or temporarily) in recent weeks – should stand ready to support these efforts. Europeans actors should emphasize that targeted relief need not change the substance of the Trump administration’s policy on Iran or reduce its leverage in potential negotiations with the country. Should Europe and the US fail to provide relief to Iran in such grave circumstances, this would turn the Iranian public against them for generations. And it would give ammunition to those in Iran who favor confrontation with the West.

Photo: IRNA

Trump Administration Pressures Global Financial Watchdog to ‘Blacklist’ Iran

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF), a global body that sets standards to combat money laundering and terrorist finance, has placed Iran back on its infamous “blacklist,” following the failure of Iranian policymakers to enact two key bills in accordance with an action plan set in 2016.

This article was originally published by Responsible Statecraft.

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF), a global body that sets standards to combat money laundering and terrorist finance, has placed Iran back on its infamous “blacklist,” following the failure of Iranian policymakers to enact two key bills in accordance with an action plan set in 2016.

The FATF statement, issued on Friday at the conclusion of the body’s latest plenary meeting, calls on members to “to apply effective countermeasures” following Iran’s failure to implement “the Palermo and Terrorist Financing Conventions in line with the FATF Standards.”

Such countermeasures include increase monitoring, reporting, and auditing of Iran-related financial transactions for all financial institutions worldwide. While members can decide how to reimpose the countermeasures, the decision taken by FATF serves as a kind of external validation of the Trump administration’s claims that the Iranian financial system is regularly used to facilitate money laundering and terrorist finance on a massive scale. This characterization is a principle justification for the administration’s “maximum pressure” sanctions campaign and U.S. officials had been dogged in pressuring FATF to call “time out” on Iran’s reform process.