Iran's Special Relationship with China Beset by 'Special Issues'

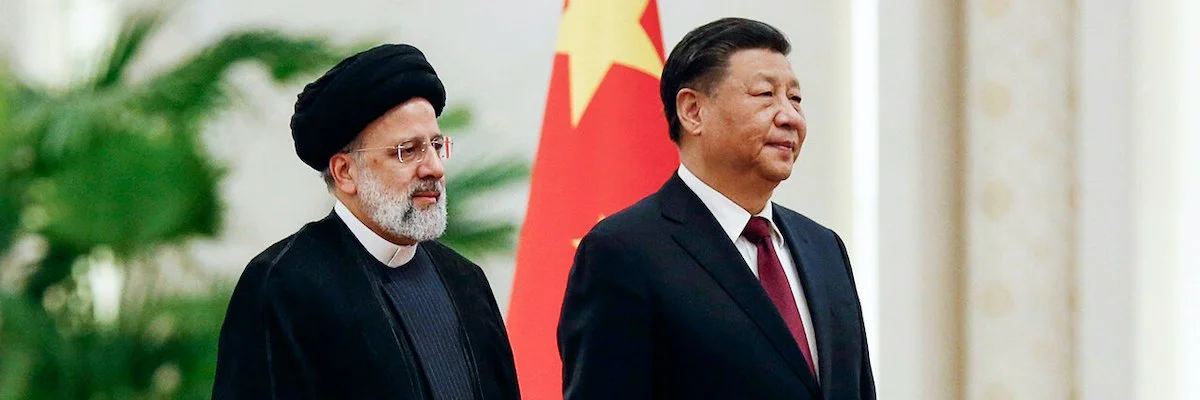

This week, Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi flew to China for a three-day state visit at the invitation of Xi Jinping, marking the first full state visit by an Iranian president in two decades.

On February 14, Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi flew to China for a three-day state visit at the invitation of Xi Jinping, marking the first full state visit by an Iranian president in two decades. For Beijing, hosting Raisi was an attempt to regain Tehran’s trust after the significant controversy generated by the China-GCC joint statement issued following Xi’s visit to Riyadh in December. For Tehran, taking a large delegation to Beijing was an opportunity to remind the world that China and Iran enjoy a special relationship.

On the eve of the visit, Iran, a government newspaper, published a 120-page special issue of its economic insert entirely focused on China-Iran relations. Given the newspaper’s affiliation and the timing of the publication, the special issue is something like a white paper on the Raisi administration’s China policy and the perceived importance of a functional partnership with China.

The cover of the special issue speaks for itself—it calls for the creation of a triangular trade relationship between Iran, China, and Russia. Another headline declares that the Raisi administration is “reconstructing broken Iran-China ties.” In his pre-departure remarks, Raisi doubled down on this message, noting that Iran “has to pursue compensation for the dysfunction that existed up until now in its relations with China.” With this statement, Raisi both cast blame on Hassan Rouhani, his predecessor, for failing to maintain stronger ties with China, while also implying that China had let Iran down by failing to begin implementation of a 25-year Comprehensive Strategic Partnership agreement signed in 2021.

Iran’s grievances aside, the overall tone of the special issue is laudatory, suggesting that the Raisi administration has chosen to overlook China’s apparent endorsement of the UAE’s claim over the three contested Persian Gulf islands, which caused an uproar in Iran following the China-GCC consultations in December. But a development just before Raisi’s trip generated new controversy.

According to reports, Chinese oil major Sinopec has withdrawn from investing in the significant Yadavaran oil field located on the Iran-Iraq border. The Iranian government began negotiating with Sinopec in 2019 to develop the project's second phase. The negotiations were slow-going, in part because of the challenges created by US secondary sanctions.

Fereydoun Kurd Zanganeh, a senior official at the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC), has denied the reports, claiming that negotiations with Sinpoec are ongoing. According to him, the Chinese energy company “has not yet announced in any way that it will not cooperate in the development of the Yadavaran field.” Whether or not Sinopec has actually withdrawn from Yadavaran, the slow pace of the negotiations and the difficulty for Chinese companies to deliver major projects—as in the case of Phase 11 of the South Pars gas field—reflect that China is an unreliable partner for Iran, at least while Iran remains under sanctions.

Nonetheless, the Raisi administration is keen to attract more Chinese investment. In an interview with ISNA published on January 28, Ali Fekri, a deputy economy minister, said that he “is not happy with the volume of the Chinese investment in Iran, as they have much greater capacity.” According Fekri, since the Raisi administration took office, the Chinese have invested $185 million in 25 projects, comprising of “21 industrial projects, two mining projects, one service project, and one agricultural project.” As indicated by the low dollar value relative to the number of investments, Chinese commitments have been limited to small and medium-sized projects. Beijing has mainly invested in projects that, according to Fekri, offer China the opportunity to import goods from Iran.

Comparative data shows Iran falling behind other countries in the race to attract Chinese investment. For instance, according to the data complied by the American Enterprise Institute, China committed $610 million in Iraq and a striking $5.5 billion in Saudi Arabia in 2022 alone. With secondary sanctions in place, the prospect of more Chinese investments in Iran is unrealistic.

Despite these obvious challenges, Iranian officials have been reluctant to admit that external factors are shaping China-Iran relations. Ahead of Raisi’s departure to China, Alireza Peyman Pak, the head of the Iran Trade Promotion Organization (ITPO), denied that Xi Jinping’s visit to Saudi Arabia in December had precipitated a cooling of Beijing’s relations with Tehran.

“Such an interpretation is by no means correct. A country with an economy of $6 trillion naturally tries to develop its economy by working with all countries,” he said. Peyman Pak pointed to recent trade data to bolster his case. “In the past ten months, we have seen a 10 percent growth in exports to China compared to the same period last year,” he added, leaving out that the growth comes from a low base—China-Iran trade has languished since 2018.

In recent months, Peyman Pak has played a prominent role in brokering memorandums of understanding between Russian and Iranian companies—part of the push for a deeper Russia-Iran economic partnership. His participation in the delegation heading to China suggests that the Raisi administration is serious about shaping a triangular trade alliance between Tehran, Moscow, and Beijing. So far, that economic alliance exists only in the form of various non-binding agreements. China and Iran signed 20 agreements worth $10 billion during Raisi’s visit.

These agreements, like those before them, have a low chance of being implemented, especially while the future of the JCPOA remains in doubt. For now, China-Iran relations are limited to the text of white papers, memorandums, and statements. For his part, Xi offered Raisi some encouraging words. He reiterated China’s opposition to “external forces interfering in Iran’s internal affairs and undermining Iran’s security and stability” and promised to work with Iran on “issues involving each other’s core interests.” No doubt, the special relationship between China and Iran is beset by special issues.

Photo: IRNA

When it Comes to Iran, China is Shifting the Balance

Xi Jinping’s recent trip to Riyadh, his first foreign visit to the Middle East since the pandemic, suggests that China may no longer seek to treat Iran and its Arab neighbours as equals.

In 2016, during his first trip to the Middle East, Chinese Premier Xi Jinping visited both Riyadh and Tehran, a reflection of China’s effort to balance relations among the regional powers of the Persian Gulf. But Xi’s recent trip to Riyadh, his first visit to the Middle East since the pandemic, suggests that China is no longer aiming to treat Iran and its Arab neighbours as equals.

Following the meetings in Riyadh, China and the GCC issued a joint statement. Four of the eighteen points that comprise the joint statement directly pertain to Iran. In the declaration, China and the GCC countries called on Iran to cooperate with the International Atomic Energy Agency as part of its obligations under the beleaguered Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Using strong and direct language, the statement additionally called for a comprehensive dialogue involving regional countries to address Iran’s nuclear programme and Iran’s malign activities in the region. The language used was less neutral than that typically seen in Chinese communiqués and instead took the tone of Saudi and Emirati talking points regarding Iran.

Iranian officials were especially vexed to see that China had effectively endorsed longstanding Emirati claims to three islands: Greater Tunb, Lesser Tunb, and Abu Musa. The islands, located in the Strait of Hormuz, were occupied by the Imperial Iranian Navy in 1971 after the withdrawal of British forces. Ever since, Iran has considered the three islands as part of its territory. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) has made periodic attempts over the last four decades to regain control of the islands, claiming that before the British withdrawal, the territories were administered by the Emirate of Sharjah. While the statement does not go so far as to declare that the islands belong the UAE, China’s call for negotiations over their status inherently undermines Iran’s claims.

The reaction of Iranian officials and the public has been sharp. The day after the statement was published, Iranian newspapers featured bitter headlines. One newspaper even provocatively questioned China’s claim over Taiwan. Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian tweeted that the three Persian Gulf islands belong to Iran and demanded respect for Iran’s territorial integrity. Meanwhile, Iran’s Assistant Foreign Minister for Asia and the Pacific met with the Chinese Ambassador to Iran, Chang Hua, to express “strong dissatisfaction” with the outcome of the China-GCC summit.

Amid the polemic generated by the China-GCC statement, the Chinese official news agency Xinhua announced that Vice Premier Hu Chunhua would visit Iran and the UAE next week. If the stopover in Tehran was intended as a Chinese gesture to ease tensions, the move is likely to backfire. While “Little Hu” had been expected to gain a prestigious seat in the Politburo Standing Committee during the recent National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), he was instead demoted from the Politburo and is expected to be removed as Vice Premier in March 2023. Considering Xi’s triumphal visit to Riyadh, the optics surrounding Hu’s planned visit to Tehran are especially bad.

As Xi begins his third term as China’s leader, he appears to be viewing relations with Iran through the prism of liability, rather than opportunity. Despite the fanfare surrounding the beginning of Iran’s long-awaited accession to the China-led Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) in September, this was a relatively shallow political move. The SCO is an organisation with a limited institutional capacity and substantial internal divisions—Iran’s accession did not herald the opening of a new era in Sino-Iranian relations.

Two issues appear to be hampering China-Iran relations. First, negotiations to restore the JCPOA have failed. With sanctions in place, Iran has struggled to attract Chinese investment and cooperation, especially when compared to Saudi Arabia and the UAE. As I argued in March, economic ties are a pillar of the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (CSP) that China and Iran have devised, but relaunching economic relations between the two countries requires successful nuclear diplomacy and the lifting of US secondary sanctions. Beijing and Tehran announced the beginning of the CSP implementation phase last January when the nuclear talks appeared likely to succeed. Today, the prospects for implementing the CSP are nill and China-Iran trade is continuing to languish at around $1 billion in total value per month.

Second, Iran’s decision to sell military drones to Russia, thereby becoming actively involved in the war in Ukraine, is proving a significant strategic miscalculation. By actively supporting Russia’s war of aggression, Iran has taken itself out of a large bloc of countries, nominally led by China, that have adopted an ambiguous position towards the conflict. This bloc, which notably includes the GCC countries, is neither aligned with Ukraine and NATO nor openly against Russia and its coalition of hardliner states. In short, Iran’s overt alignment with Russia is at odds with China’s approach.

Meanwhile, the evident strains in US relations with Saudi Arabia and the UAE have created an opening for China to deepen ties with the two regional powers. In some respects, this opening has diminished China’s need to cultivate a deeper partnership with Iran. Ties with Tehran had long been attractive as a means to counterbalance US influence in the region. But Beijing’s success in building deeper relations with Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, two capitals that have long taken their cues from Washington, suggests that China is gaining new means to check US power in the Middle East.

China-Iran relations have seesawed plenty over the years, but the outcome of Xi’s visit to Saudi Arabia suggests a new and more negative outlook for bilateral ties. While Iran tries in vain to “turn East,” China may be shifting away.

Photo: IRNA

Iran Gains Prestige, Not Power, By Joining China-Led Bloc

Although Iran’s accession to the SCO—which may take up to two years to complete—appears significant, the move is unlikely to substantially change Iran’s geopolitical position.

Last week, after fifteen long years in political limbo, Iran’s application to join the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) was finally approved. Iran first showed interest in the Chinese-led organisation in 2004, when it achieved non-member observer status. Although it first sought full membership in 2008, China and other member-states remained wary, primarily due to the impact of U.S-led multilateral sanctions, which made further political and economic entanglement with Iran a risky proposition. While India and Pakistan were admitted in 2017, continued instability in American policy towards Iran kept Sino-Iranian rapprochement on the back-burner. Since the Biden administration began to signal that it was open to negotiations with Iran, China made a renewed push for improved relations, culminating in the signing of a bilateral Comprehensive Strategic Partnership agreement with Iran in May of this year.

Despite these developments, Sino-Iranian relations remain limited and although Iran’s accession to the SCO—which may take up to two years to complete—appears significant, the move is unlikely to substantially change Iran’s geopolitical position. Despite Iranian rhetoric, the SCO is by no means an anti-Western alliance and is unlikely to furnish Iran much beyond symbolic support for its regional and international objectives. Iranian membership is also not a guarantee of increased Chinese investment or favourable policy decisions. In terms of dividends, Iran will have to make do with propaganda, prestige, and nationalist theatre for international and domestic audiences.

The Iranian government has touted membership in SCO as a means of opposing the United States and ending Iran’s diplomatic and economic isolation. Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi was unrestrained in his comments at the SCO Summit in Dushanbe, the capital of Tajikistan. “The world has entered a new era,” Raisi said, where “hegemony and unilateralism are failing.” He painted Iran’s membership in the SCO as emblematic of an increasingly multi-polar world, where smaller powers could work in tandem to limit the influence of larger powers. More to the point, he called on member states to support Iran’s civilian nuclear program and resist sanctions, which he called a form of “economic terrorism.”

Compared to the Iranian side, the Chinese press was more reserved. A report from Xinhua emphasized the SCO’s ability to foster a “regional consensus” and to connect Iran “to the economic infrastructure of Asia.” The news was presented alongside developments related to Afghanistan and Tajikistan, and while described as a “diplomatic success,” Iran’s membership was not cast as a key outcome fo the summit. Raisi’s exhortations to resist American unilateralism were not reported on at all. Xi Jinping’s summit address did not even mention Iran by name.

Despite the lofty rhetoric of the Iranian president, there are few ways in which the SCO will be able to directly confront American hegemony. As noted by Nicole Grajewski, the SCO is “governed by consensus, which limits the extent of substantive cooperation” between states with divergent policies and competing objectives. It also lacks any legal mechanisms to enforce its decisions or punish member-states that violate its policies or have conflict with other members. Far from the “anti-NATO” it has been portrayed to be, the SCO is more a “forum for discussion and engagement than a formal regional alliance.” Two of the eight present members, India and Pakistan, are close U.S allies, and neither China nor Russia are keen to openly challenge the U.S in the Middle East or Central Asia.

In short, Iran will gain the ability to participate in these discussions, but not in a way that is likely to strongly influence the organization or its policies. China and the rest of the member-states will be keen to avoid alienating the Arab states that see Iran as a regional rival. In a move that seems targeted directly at balancing this concern, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Egypt were also admitted during the Dushanbe summit as “dialogue partners,” joining nations like Turkey and Azerbaijan. While not full members, the presence of these voices will limit how much sway Iran will have at future SCO summits.

Furthermore, despite its own rhetorical commitment to facilitating trade, economic, and cultural ties between members, the SCO’s success in these fields has been limited. In terms of tangible projects, the SCO has mostly stuck to regional security initiatives like counter-terrorism intelligence sharing, cross-border efforts to fight drug trafficking, and joint military exercises. While the organization has lately attempted to re-brand itself as an economic development platform, it still lacks any institutions for multilateral development finance. Beijing and Moscow also have divergent interests when it comes to major issues like free trade zones, and questions remain as to whether the organization can function as an actual forum for holding practical negotiations between member states, rather than “simply becoming their vehicle for norm-making power projection.”

China and Iran have set ambitious targets to increase trade for nearly a decade, but bilateral trade remains modest despite repeated commitments, discussions, and international summits. There remain substantial barriers to investment. Chinese investors have been urged for years to invest in Iran’s free economic zones in Maku, Qeshm, and Arvand, but investment remains limited. While China is more than happy to ignore sanctions when it comes to oil imports, outside this strategic trade, Chinese firms remain unconvinced that the profit is worth the risk of doing business, and privately grumble about the difficulty of working with Iranian partners. Iranians also face disruption and competition from Chinese goods and services, leading to popular discontent and political blowback from Iranian companies that have profited from the absence of both Western and Chinese competitors. Although there is no question that there is vast potential in economic co-operation between China and Iran, these are not minor issues, and there is little reason to believe that the SCO will provide a forum to address the barriers.

The SCO provides an impressive stage for China and Iran to enact their shared opposition to Western sanctions, hegemony, and unilateralism. But the realities of international political economy and the conflicting agendas of the body’s member states means that joining the SCO is unlikely to empower Iran in a meaningful way.

Photo: Government of Iran

Iran’s Pact With China Is Bad News for the West

Tehran’s new strategic partnership with Beijing will give the Chinese a strategic foothold and strengthen Iran’s economy and regional clout.

By Alam Saleh and Zakieh Yazdanshenas

A recently leaked document suggests that China and Iran are entering a 25-year strategic partnership in trade, politics, culture, and security.

Cooperation between China and Middle Eastern countries is neither new nor recent. Yet what distinguishes this development from others is that both China and Iran have global and regional ambitions, both have confrontational relationships with the United States, and there is a security component to the agreement. The military aspect of the agreement concerns the United States, just as last year’s unprecedented Iran-China-Russia joint naval exercise in the Indian Ocean and Gulf of Oman spooked Washington.

China’s growing influence in East Asia and Africa has challenged U.S. interests, and the Middle East is the next battlefield on which Beijing can challenge U.S. hegemony—this time through Iran. This is particularly important since the agreement and its implications go beyond the economic sphere and bilateral relations: It operates at the internal, regional, and global level.

Internally, the agreement can be an economic lifeline for Iran, saving its sanctions-hit, cash-strapped economy by ensuring the sale of its oil and gas to China. In addition, Iran will be able to use its strategic ties with China as a bargaining chip in any possible future negotiations with the West by taking advantage of its ability to expand China’s footprint in the Persian Gulf.

While there are only three months left before the 2020 U.S. presidential election, closer scrutiny of the new Iran-China strategic partnership could jeopardize the possibility of a Republican victory. That’s because the China-Iran strategic partnership proves that the Trump administration’s maximum pressure strategy has been a failure; not only did it fail to restrain Iran and change its regional behavior, but it pushed Tehran into the arms of Beijing.

In the long term, Iran’s strategic proximity to China implies that Tehran is adapting the so-called “Look East” policy in order to boost its regional and military power and to defy and undermine U.S. power in the Persian Gulf region.

For China, the pact can help guarantee its energy security. The Persian Gulf supplies more than half of China’s energy needs. Thus, securing freedom of navigation through the Persian Gulf is of great importance for China. Saudi Arabia, a close U.S. ally, has now become the top supplier of crude oil to China, as Chinese imports from the kingdom in May set a new record of 2.16 million barrels per day. This dependence is at odds with China’s general policy of diversifying its energy sources and not being reliant on one supplier. (China’s other Arab oil suppliers in the Persian Gulf region have close security ties with the United States.)

China fears that as the trade war between the two countries intensifies, the United States may put pressure on those countries not to supply Beijing with the energy it needs. A comprehensive strategic partnership with Iran is both a hedge and an insurance policy; it can provide China with a guaranteed and discounted source of energy.

Chinese-Iranian ties will inevitably reshape the political landscape of the region in favor of Iran and China, further undermining U.S. influence. Indeed, the agreement allows China to play a greater role in one of the most important regions in the world. The strategic landscape has shifted since the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq. In the new regional order, transnational identities based on religious and sectarian divisions spread and changed the essence of power dynamics.

These changes, as well as U.S. troop withdrawals and the unrest of the Arab Spring, provided an opportunity for middle powers like Iran to fill the gaps and to boost their regional power. Simultaneously, since Xi Jinping assumed power in 2012, the Chinese government has expressed a stronger desire to make China a world power and to play a more active role in other regions. This ambition manifested itself in introducing the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which highlighted the strategic importance of the Middle East.

China grasps Iran’s position and importance as a regional power in the new Middle East. Regional developments in recent years have consolidated Iran’s influence. Unlike the United States, China has adopted an apolitical development-oriented approach to the region, utilizing Iran’s regional power to expand economic relations with nearby countries and establish security in the region through what it calls developmental peace—rather than the Western notion of democratic peace. It’s an approach that authoritarian states in the Middle East tend to welcome.

U.S. President Donald Trump’s withdrawal from the nuclear deal with Iran in 2018, and the subsequent introduction of the maximum pressure policy, was the last effort by the U.S. government to halt Iran’s growing influence in the region. Although this policy has hit Iran’s economy hard, it has not been able to change the country’s ambitious regional and military policies yet. As such, the newfound strategic cooperation between China and Iran will further undermine U.S. leverage, paving the way for China to play a more active role in the Middle East.

The Chinese-Iranian strategic partnership will also impact neighboring regions, including South Asia. In 2016, India and Iran signed an agreement to invest in Iran’s strategic Chabahar Port and to construct the railway connecting the southeastern port city of Chabahar to the eastern city of Zahedan and to link India to landlocked Afghanistan and Central Asia. Iran now accuses India of delaying its investments under U.S. pressure and has dismissed India from the project.

While Iranian officials have refused to link India’s removal from Chabahar-Zahedan project to the new 25-year deal with China, it seems that India’s close ties to Washington led to this decision. Replacing India with China in such a strategic project will alter the balance of power in South Asia to the detriment of New Delhi.

China now has the chance to connect Chabahar Port to Gwadar in Pakistan, which is a critical hub in the BRI program. Regardless of what Washington thinks, the new China-Iran relationship will ultimately undermine India’s interests in the region, particularly if Pakistan gets on board. The implementation of Iran’s proposal to expand the existing China-Pakistan Economic Corridor along northern, western, and southern axes and link Gwadar Port in Pakistan to Chabahar and then to Europe and to Central Asia through Iran by a rail network is now more probable. If that plan proceeds, the golden ring consisting of China, Pakistan, Iran, Russia, and Turkey will turn into the centerpiece of BRI, linking China to Iran and onward to Central Asia, the Caspian Sea, and to the Mediterranean Sea through Iraq and Syria.

On July 16, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani announced that Jask Port would become the country’s main oil loading point. By placing a greater focus on the development of the two strategic ports of Jask and Chabahar, Iran is attempting to shift its geostrategic focus from the Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Oman. This would allow Tehran to avoid the tense Persian Gulf region, reduces the journey distance for oil tankers shipping Iranian oil, and also enables Tehran to close the Strait of Hormuz when needed.

The bilateral agreement provides China with an extraordinary opportunity to participate in the development of this port. China will be able to add Jask to its network of strategic hubs in the region. According to this plan, regional industrial parks developed by Chinese companies in some Persian Gulf countries will link up to ports where China has a strong presence. This interconnected network of industrial parks and ports can further challenge the United States’ dominant position in the region surrounding the strategically vital Strait of Hormuz.

A strategic partnership between Iran and China will also affect the great-power rivalry between the United States and China. While China remains the largest trading partner of the United States and there are still extensive bilateral relations between the two global powers, their competition has intensified in various fields to the point that many observers argue the world is entering a new cold war. Given the geopolitical and economic importance of the Middle East, the deal with Iran gives China yet another perch from which it can challenge U.S. power.

Meanwhile, in addition to ensuring its survival, Tehran is going to take advantage of ties with Beijing to consolidate its regional position. Last but not least, while the United States has been benefiting from rivalry and division in the region, Chinese-Iranian partnership could eventually reshape the region’s security landscape by promoting stability through the Chinese approach of developmental peace.

Alam Saleh is a lecturer in Iranian studies at Australian National University’s Centre for Arab and Islamic Studies. He is also a council member of the British Society for Middle Eastern Studies. Follow him at @alamsaleh1.

Zakiyeh Yazdanshenas is a research fellow at the Center for Middle East Strategic Studies. Her expertise mainly focuses on great-power rivalries in the Middle East. Follow her at @YzdZakiyeh.

Photo: IRNA