To Avoid a Currency Crunch, Iranian Automakers Are Trading Nuts for Bolts

The outlook for the Iranian automotive industry looked dire until Iranian automakers stumbled upon an unexpected solution.

In a typical year, 10 out of every 100 dollars that Iran spends on Chinese goods goes towards car parts. While the China-Iran trade relationship has languished under sanctions, China has remained a critical supplier for the Iranian automotive industry, which continues to produce over one million automobiles annually.

But over the last year, Iranian automakers have struggled to keep the parts flowing. Parts imports from China totalled $653 million in 2024, a precipitous 43 percent decline when compared to the previous year.

The fall in imports has led to a shortage of car parts in Iran, with consumers facing long wait times and soaring prices. The impact has been most acute for Iran’s private sector automakers, who mainly assemble cars using complete knock-down kits imported from China. Whilst Iran’s state-owned automakers are supported by a large ecosystem of domestic parts manufacturers, private-sector automakers remain heavily dependent on Chinese imports to keep their customers’ cars on the road.

The main cause for declining imports has been a lack of access to foreign currency, a consequence of US secondary sanctions restricting Iran’s banking relations with China. Even though Iranian oil exports to China have rebounded in recent years, they have not alleviated Iran’s foreign exchange crisis. Iranian companies seeking to import goods from China have struggled to receive timely allocations of renminbi through the Central Bank of Iran’s foreign exchange market.

As the currency bottleneck grew tighter over the course of 2024, imports continued to fall, and by the summer, the situation was being described as a “crisis.” In September, imports of car parts from China hit a nadir, with just $26 million worth of parts departing for Iran that month—a 65 percent year-on-year drop.

The outlook for the Iranian automotive industry looked dire until Iranian automakers stumbled upon an unexpected solution. In need of a new source of renminbi, many Iranian automotive firms turned to the pistachio business. Like oil, pistachios are a valuable commodity in which Iran is a world-leading producer. Unlike oil, pistachios are exempt from secondary sanctions.

Iranian automotive companies began purchasing pistachios from growers and leveraging their logistics networks to ship them to China. As a result, Iranian pistachio exports to China quickly surged to historic highs, enabling a modest recovery in car parts imports. In the last six months of 2024, Iran exported $195 million worth of in-shell pistachios to China—more than 2.5 times the volume achieved in the same period in 2023.

Pistachio growers and wholesalers, however, were not happy. Many Iranian pistachio wholesalers had given up on exports—leaving the Chinese market open to new entrants. The requirement to repatriate export earnings through the centralised foreign exchange market made margins unattractive for many agricultural firms. But for automotive companies, profit from pistachio sales was never the primary objective. Selling nuts provided a quick way for them to earn the foreign currency they needed to import car parts, which could then be resold in Iran at much higher margins. By October, industry leaders were complaining of “chaos in Iran's pistachio trade” as automakers turned into “inefficient competitors of Iran's real pistachio exporters.”

Pistachio exporters are reportedly seeking an understanding with the automakers who edged onto their turf. They plan to sell their foreign currency to automakers at a rate agreed with the supervision of the Central Bank of Iran, ensuring sufficient margins to incentivise them to prioritise exports once again.

Sanctions have not crushed the Iranian economy, but they have made pistachios more valuable than oil, forced importers to become exporters, and pushed automakers into competition with farmers. In adapting to sanctions pressure, the solution to one crisis can beget another, leaving a country trading nuts for bolts.

Photo: IRNA

As Iran Sells More Oil to China, the U.S. Gains Leverage

A new report, citing data from Kpler, an analytics company, claims that Iranian oil exports to China will reach 1.5 million barrels per day this month, the highest level in a decade.

A new report from Bloomberg, citing data from Kpler, an analytics company, claims that Iranian oil exports to China will reach 1.5 million barrels per day this month, the highest level in a decade. The report has led to a flurry of criticism from hawks that President Biden is failing to enforce U.S. sanctions on Iran’s oil exports and thereby gifting Iran billions of dollars in oil revenue. But in reality, Iran appears unable to spend most of the money—a situation that is giving Biden leverage he can use in future negotations.

Iran’s resurgent oil exports are earning the country a lot of money. The crude oil price is currently hovering at around $80. Iran discounts its oil for Chinese customers, so the actual selling price is probably closer to $74 dollars per barrel. At this price, Iran’s 1.5 million barrels per day of exports are earning the country around $3.3 billion per month.

These back of the envelope calculations are necessary because China’s customs administration stopped reporting the value and volume of oil imported from Iran back in May 2019, when the Trump administration revoked a series of waivers permitting limited purchases of Iranian oil by select countries. When looking to the Chinese data alone, Iran’s export revenue appears much smaller than it is, hiding the true trade balance.

In the most recent three months for which we have customs data, Iran’s imports from China averaged $826 million. In the same period, Iran’s non-oil exports to China averaged $357 million. When not counting Iran’s oil exports, Iran appears to be running a trade deficit with China of around $469 million. But when adding the reasonable estimate of $3.3 billion of oil exports, the monthly trade balance swings dramatically in Iran’s favor. In recent months, Iran has likely run a trade surplus with China of around $2.8 billion per month.

In other words, Iran is earning billions of dollars it appears unable to spend. After all, Chinese goods, especially parts and machinery, are a lifeline for Iranian industry. If Iran was able to buy more Chinese goods, it would be doing so. Two other data points confirm this interpretation. Exports from the UAE to Iran remain depressed, so Chinese goods are not arriving in Iran indirectly. Purchasing managers’ index data for the manufacturing sector also indicates that Iranian firms continue to struggle with low inventories of raw materials and intermediate goods. Moreover, Iran is continuing to doggedly pursue the release of its frozen assets, including $6 billion that will be made available for humanitarian trade as part of the recent U.S.-Iran prisoner deal. Iran would not be so desperate to strike such deals were its oil revenues in China readily accessible. In short, Iran is selling its oil and earning money, but it is not getting the full economic benefit from the surge in oil exports.

Chinese exporters and their banks remain wary of trading with Iran, where entities and whole sectors remain subject to U.S. secondary sanctions. For most Chinese multinational companies, trading with Iran is not worth the risk. In the first six months of this year, Chinese exports to Iran averaged $898 million per month. Exports remain 35% lower than in the first six months of 2017, the most recent year during which Iran enjoyed sanctions relief.

It remains to be seen whether Iran can sustain this new, higher level of oil exports. Oil markets can be fickle, and China’s economic wobbles could depress demand. But for now, Iran’s significant trade surplus with China also means that its renminbi reserves must be growing. This is a novel situation. Historically Iran has run a small trade surplus with China. Between January 2012, when the Obama administration launched devastating financial and energy sanctions on Iran, and January 2016, when the implementation of the nuclear deal granted Iran significant sanctions relief, the average monthly trade surplus was just $511 million (China’s purchases of Iranian oil are reflected in customs data for this period). In other words, assuming its oil revenues are stuck in China, Iran’s reserves are now growing four times faster than in that period.

At first glance, this might look like a major failure for the Biden administration. Biden purposefully maintained the “maximum pressure” sanctions imposed by Trump in an effort to sustain leverage for negotiations and Iranian oil exports remain subject to U.S. secondary sanctions. But those who claim that Biden is failing to enforce his sanctions are failing to see the wisdom of the current U.S. enforcement posture.

First, Biden is loath to deepen already heightened tensions with China. Sanctioning Chinese refiners for their purchases of Iranian oil, thereby targeting China’s energy security, would be a dramatic escalation in the growing economic competition between Washington and Beijing. Second, such escalation would be entirely pointless given the circumstances around Iran’s oil exports—namely that Iran is not getting the normal economic benefits. Given that Iran is earning more money but cannot spend it, the U.S. is actually gaining leverage for future negotiations.

Unlike Trump, Biden has made a serious effort to engage in nuclear diplomacy with Iran and is likely to continue those efforts if there is a reasonable opportunity to achieve a new diplomatic agreement that contains Iran’s nuclear program. But U.S. negotiators have struggled to make a compelling offer to their Iranian counterparts. Many Iranian policymakers felt the promised economic uplift of sanctions relief would be too small. Iran’s opening gambit in the negotiations with Biden included the claim that sanctions had inflicted $1 trillion of damage to Iran’s economy and that Iran was owed compensation.

With its oil exports significantly depressed, Iran has been unable to significantly grow its foreign exchange reserves, which the IMF estimates at around $120 billion. If Iranian officials believe that they need to remediate $1 trillion of economic damage, the windfall represented by the unfreezing of foreign exchange reserves does not count for much.

The longer the sanctions remain in place, the more money will be needed to undo the cumulative effects of U.S. sanctions, which have now hobbled Iran’s economy for over a decade. It is politically impossible for Biden to promise any kind of compensation for Iran—the best that the U.S. can do is promise to once again unfreeze Iran’s own money as part of a new diplomatic agreement.

For this reason, it is a good thing if Iran’s reserves are growing. Iran’s oil exports to China are kind of like payments made as part of a deferred annuity insurance contract. One day, Iran will be able to cash out on that policy. But it can only cash out if it meets the conditions set by the U.S. In other words, every barrel of oil Iran is currently selling to China is increasing U.S. leverage for future talks. It would be wise to let the oil flow.

Photo: Canva

When it Comes to Middle East Diplomacy, Chinese and European Interests Align

In March, China managed to a broker a détente between Iran and Saudi Arabia, achieving a diplomatic breakthrough that had eluded European governments. But Europe and China have shared interests in the region and there is scope for the two powers to work together to foster further multilateral diplomacy.

A version of this article was originally published in French in Le Monde.

In March, China managed to a broker a détente between Iran and Saudi Arabia, achieving a diplomatic breakthrough that had eluded European governments. But Europe and China have shared interests in the region and there is scope for the two powers to work together to foster further multilateral diplomacy.

Europe and China, which both depend on energy exports from the Persian Gulf, have long relied on the US-led security architecture in the region. But the 2019 attacks on oil tankers in the UAE and oil installations in Saudi Arabia, widely attributed to Iran, were a watershed moment. Shifting US interests and President Trump’s erratic reaction to those attacks forced the Chinese and Europeans to take more responsibility for regional security over the last four years.

In 2020, China presented its idea for regional security in the Persian Gulf, arguing that with a multilateral effort, the Persian Gulf region can become “an oasis of security.” In the time since, the agreement between Saudi Arabia and Iran, signed in March, can be considered an outcome of such efforts.

European governments have also sought to back multilateral diplomacy. France was intent on creating a platform for Tehran and Riyadh to engage in dialogue. President Macron helped launch the Baghdad Conference for Cooperation and Partnership that was held in August 2021. The conference was a unique opportunity to gather countries that had not sat around the same table for years. Officials from Iraq, Iran, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, in addition to Egypt, Jordan, Turkey, and France participated. Oman and Bahrain joined the second gathering which took place last December in Amman, Jordan.

The European Union also expressed its support for the Baghdad process. Joseph Borrell said during the Second meeting that “promoting peace and stability in the wider Gulf region… are key priorities for the EU.” Adding that “we stand ready to engage with all actors in the region in a gradual and inclusive approach.”

The Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council on a strategic partnership with the Gulf reflects the EU’s keenness on expanding its engagements with the region, particularly on economic ties. The partnership is focused on the GCC, but it mentions that “involvement of other key Gulf countries in the partnership may also be considered as relations develop and mature”—a reference to Iran and Iraq.

Clearly, China and the European Union have multiple areas of mutual concern in the Persian Gulf region. Ensuring freedom of navigation, the undisrupted flow of oil and gas from the region, and non-proliferation of nuclear weapons are shared priorities. But while China is now a central player in the strategic calculations of all states in the region, the Europeans are being largely left out.

European diplomatic outreach has faltered in the face of new political pressures arising from Iran’s continued nuclear escalations, its involvement in Russia’s war against Ukraine, and its repression of ongoing protests for democratic change.

The French president was coincidently in China when the Beijing Agreement was signed, and he welcomed the rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Iran. Given shared interests, European officials must now find ways to engage with Chinese counterparts on fostering greater regional diplomacy in the Persian Gulf.

There are reports that a regional summit will take place in Beijing later this year, involving all GCC states, Iran and Iraq. This is an important opportunity for multilateral dialogue and cooperation. European governments should consult with regional players and China to secure a seat at the meeting. The EU can help regional countries find ways to jointly tackle basic issues that have impeded economic growth which have resulted in spillover effects such as increased food insecurity and inability to mitigate the rising challenges of climate change.

In parallel, the Baghdad Conference could emerge as an EU-backed platform for economic cooperation in tandem to the now ongoing political and security dialogue process in China. The EU can draw in regional countries to help with reconstruction efforts in Iraq, a country that is in dire need of foreign investment. Given the shuttle diplomacy conducted by Iraqi officials between Iran and Saudi Arabia, and considering the role of France and the EU in the Baghdad conference, it would be apt to explore EU-supported joint economic projects in Iraq, especially those projects that create mutual economic interests between Iran and Saudi Arabia.

Whether in Baghdad, Amman, or Beijing, inclusive regional gatherings are needed to address common economic challenges facing all eight countries surrounding the Persian Gulf. Europe can make significant contributions towards regional dialogue on economic integration by helping to create multilateral platforms, transfer knowhow and technology, and provide financial support. These are areas where China has significantly increased its activities, but European countries enjoy far greater experience in establishing the institutions and infrastructure needed for regional economic development. European officials can leverage this experience to support regional diplomacy. Such efforts would also cement European regional influence at a time when US influence may be waning.

The newly appointed EU Special Representative for Gulf Affairs, Luigi Di Maio, should directly oversee and coordinate initiatives in support of economic diplomacy and integration in the region, finding common ground with China to head off competition. Achieving security through stronger diplomacy and deeper economic ties represents a transformative goal that the region can rally around.

Photo: IRNA

Iran's Special Relationship with China Beset by 'Special Issues'

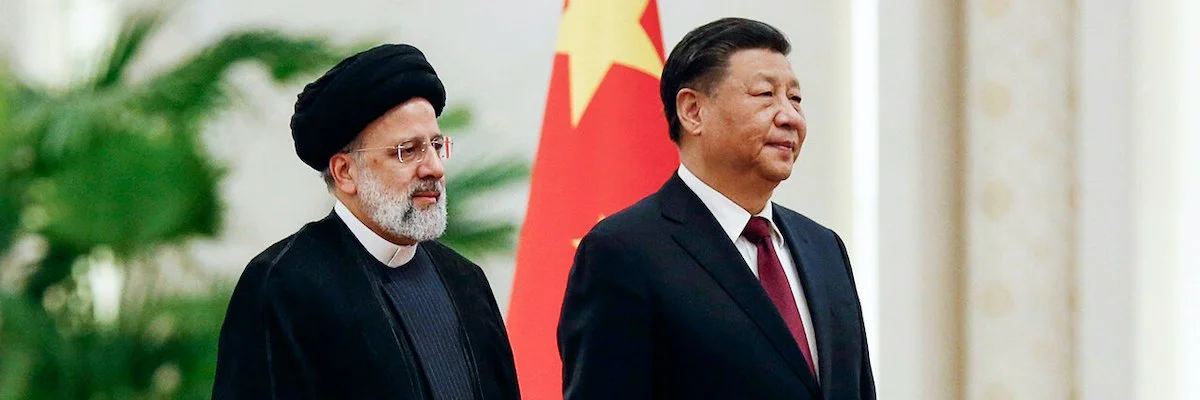

This week, Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi flew to China for a three-day state visit at the invitation of Xi Jinping, marking the first full state visit by an Iranian president in two decades.

On February 14, Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi flew to China for a three-day state visit at the invitation of Xi Jinping, marking the first full state visit by an Iranian president in two decades. For Beijing, hosting Raisi was an attempt to regain Tehran’s trust after the significant controversy generated by the China-GCC joint statement issued following Xi’s visit to Riyadh in December. For Tehran, taking a large delegation to Beijing was an opportunity to remind the world that China and Iran enjoy a special relationship.

On the eve of the visit, Iran, a government newspaper, published a 120-page special issue of its economic insert entirely focused on China-Iran relations. Given the newspaper’s affiliation and the timing of the publication, the special issue is something like a white paper on the Raisi administration’s China policy and the perceived importance of a functional partnership with China.

The cover of the special issue speaks for itself—it calls for the creation of a triangular trade relationship between Iran, China, and Russia. Another headline declares that the Raisi administration is “reconstructing broken Iran-China ties.” In his pre-departure remarks, Raisi doubled down on this message, noting that Iran “has to pursue compensation for the dysfunction that existed up until now in its relations with China.” With this statement, Raisi both cast blame on Hassan Rouhani, his predecessor, for failing to maintain stronger ties with China, while also implying that China had let Iran down by failing to begin implementation of a 25-year Comprehensive Strategic Partnership agreement signed in 2021.

Iran’s grievances aside, the overall tone of the special issue is laudatory, suggesting that the Raisi administration has chosen to overlook China’s apparent endorsement of the UAE’s claim over the three contested Persian Gulf islands, which caused an uproar in Iran following the China-GCC consultations in December. But a development just before Raisi’s trip generated new controversy.

According to reports, Chinese oil major Sinopec has withdrawn from investing in the significant Yadavaran oil field located on the Iran-Iraq border. The Iranian government began negotiating with Sinopec in 2019 to develop the project's second phase. The negotiations were slow-going, in part because of the challenges created by US secondary sanctions.

Fereydoun Kurd Zanganeh, a senior official at the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC), has denied the reports, claiming that negotiations with Sinpoec are ongoing. According to him, the Chinese energy company “has not yet announced in any way that it will not cooperate in the development of the Yadavaran field.” Whether or not Sinopec has actually withdrawn from Yadavaran, the slow pace of the negotiations and the difficulty for Chinese companies to deliver major projects—as in the case of Phase 11 of the South Pars gas field—reflect that China is an unreliable partner for Iran, at least while Iran remains under sanctions.

Nonetheless, the Raisi administration is keen to attract more Chinese investment. In an interview with ISNA published on January 28, Ali Fekri, a deputy economy minister, said that he “is not happy with the volume of the Chinese investment in Iran, as they have much greater capacity.” According Fekri, since the Raisi administration took office, the Chinese have invested $185 million in 25 projects, comprising of “21 industrial projects, two mining projects, one service project, and one agricultural project.” As indicated by the low dollar value relative to the number of investments, Chinese commitments have been limited to small and medium-sized projects. Beijing has mainly invested in projects that, according to Fekri, offer China the opportunity to import goods from Iran.

Comparative data shows Iran falling behind other countries in the race to attract Chinese investment. For instance, according to the data complied by the American Enterprise Institute, China committed $610 million in Iraq and a striking $5.5 billion in Saudi Arabia in 2022 alone. With secondary sanctions in place, the prospect of more Chinese investments in Iran is unrealistic.

Despite these obvious challenges, Iranian officials have been reluctant to admit that external factors are shaping China-Iran relations. Ahead of Raisi’s departure to China, Alireza Peyman Pak, the head of the Iran Trade Promotion Organization (ITPO), denied that Xi Jinping’s visit to Saudi Arabia in December had precipitated a cooling of Beijing’s relations with Tehran.

“Such an interpretation is by no means correct. A country with an economy of $6 trillion naturally tries to develop its economy by working with all countries,” he said. Peyman Pak pointed to recent trade data to bolster his case. “In the past ten months, we have seen a 10 percent growth in exports to China compared to the same period last year,” he added, leaving out that the growth comes from a low base—China-Iran trade has languished since 2018.

In recent months, Peyman Pak has played a prominent role in brokering memorandums of understanding between Russian and Iranian companies—part of the push for a deeper Russia-Iran economic partnership. His participation in the delegation heading to China suggests that the Raisi administration is serious about shaping a triangular trade alliance between Tehran, Moscow, and Beijing. So far, that economic alliance exists only in the form of various non-binding agreements. China and Iran signed 20 agreements worth $10 billion during Raisi’s visit.

These agreements, like those before them, have a low chance of being implemented, especially while the future of the JCPOA remains in doubt. For now, China-Iran relations are limited to the text of white papers, memorandums, and statements. For his part, Xi offered Raisi some encouraging words. He reiterated China’s opposition to “external forces interfering in Iran’s internal affairs and undermining Iran’s security and stability” and promised to work with Iran on “issues involving each other’s core interests.” No doubt, the special relationship between China and Iran is beset by special issues.

Photo: IRNA

When it Comes to Iran, China is Shifting the Balance

Xi Jinping’s recent trip to Riyadh, his first foreign visit to the Middle East since the pandemic, suggests that China may no longer seek to treat Iran and its Arab neighbours as equals.

In 2016, during his first trip to the Middle East, Chinese Premier Xi Jinping visited both Riyadh and Tehran, a reflection of China’s effort to balance relations among the regional powers of the Persian Gulf. But Xi’s recent trip to Riyadh, his first visit to the Middle East since the pandemic, suggests that China is no longer aiming to treat Iran and its Arab neighbours as equals.

Following the meetings in Riyadh, China and the GCC issued a joint statement. Four of the eighteen points that comprise the joint statement directly pertain to Iran. In the declaration, China and the GCC countries called on Iran to cooperate with the International Atomic Energy Agency as part of its obligations under the beleaguered Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Using strong and direct language, the statement additionally called for a comprehensive dialogue involving regional countries to address Iran’s nuclear programme and Iran’s malign activities in the region. The language used was less neutral than that typically seen in Chinese communiqués and instead took the tone of Saudi and Emirati talking points regarding Iran.

Iranian officials were especially vexed to see that China had effectively endorsed longstanding Emirati claims to three islands: Greater Tunb, Lesser Tunb, and Abu Musa. The islands, located in the Strait of Hormuz, were occupied by the Imperial Iranian Navy in 1971 after the withdrawal of British forces. Ever since, Iran has considered the three islands as part of its territory. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) has made periodic attempts over the last four decades to regain control of the islands, claiming that before the British withdrawal, the territories were administered by the Emirate of Sharjah. While the statement does not go so far as to declare that the islands belong the UAE, China’s call for negotiations over their status inherently undermines Iran’s claims.

The reaction of Iranian officials and the public has been sharp. The day after the statement was published, Iranian newspapers featured bitter headlines. One newspaper even provocatively questioned China’s claim over Taiwan. Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian tweeted that the three Persian Gulf islands belong to Iran and demanded respect for Iran’s territorial integrity. Meanwhile, Iran’s Assistant Foreign Minister for Asia and the Pacific met with the Chinese Ambassador to Iran, Chang Hua, to express “strong dissatisfaction” with the outcome of the China-GCC summit.

Amid the polemic generated by the China-GCC statement, the Chinese official news agency Xinhua announced that Vice Premier Hu Chunhua would visit Iran and the UAE next week. If the stopover in Tehran was intended as a Chinese gesture to ease tensions, the move is likely to backfire. While “Little Hu” had been expected to gain a prestigious seat in the Politburo Standing Committee during the recent National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), he was instead demoted from the Politburo and is expected to be removed as Vice Premier in March 2023. Considering Xi’s triumphal visit to Riyadh, the optics surrounding Hu’s planned visit to Tehran are especially bad.

As Xi begins his third term as China’s leader, he appears to be viewing relations with Iran through the prism of liability, rather than opportunity. Despite the fanfare surrounding the beginning of Iran’s long-awaited accession to the China-led Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) in September, this was a relatively shallow political move. The SCO is an organisation with a limited institutional capacity and substantial internal divisions—Iran’s accession did not herald the opening of a new era in Sino-Iranian relations.

Two issues appear to be hampering China-Iran relations. First, negotiations to restore the JCPOA have failed. With sanctions in place, Iran has struggled to attract Chinese investment and cooperation, especially when compared to Saudi Arabia and the UAE. As I argued in March, economic ties are a pillar of the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (CSP) that China and Iran have devised, but relaunching economic relations between the two countries requires successful nuclear diplomacy and the lifting of US secondary sanctions. Beijing and Tehran announced the beginning of the CSP implementation phase last January when the nuclear talks appeared likely to succeed. Today, the prospects for implementing the CSP are nill and China-Iran trade is continuing to languish at around $1 billion in total value per month.

Second, Iran’s decision to sell military drones to Russia, thereby becoming actively involved in the war in Ukraine, is proving a significant strategic miscalculation. By actively supporting Russia’s war of aggression, Iran has taken itself out of a large bloc of countries, nominally led by China, that have adopted an ambiguous position towards the conflict. This bloc, which notably includes the GCC countries, is neither aligned with Ukraine and NATO nor openly against Russia and its coalition of hardliner states. In short, Iran’s overt alignment with Russia is at odds with China’s approach.

Meanwhile, the evident strains in US relations with Saudi Arabia and the UAE have created an opening for China to deepen ties with the two regional powers. In some respects, this opening has diminished China’s need to cultivate a deeper partnership with Iran. Ties with Tehran had long been attractive as a means to counterbalance US influence in the region. But Beijing’s success in building deeper relations with Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, two capitals that have long taken their cues from Washington, suggests that China is gaining new means to check US power in the Middle East.

China-Iran relations have seesawed plenty over the years, but the outcome of Xi’s visit to Saudi Arabia suggests a new and more negative outlook for bilateral ties. While Iran tries in vain to “turn East,” China may be shifting away.

Photo: IRNA

EU Embargo of Russian Oil Spells Trouble for Iran

European Union leaders have agreed on a landmark embargo of Russian oil that will seek to slash imports by 90 percent by the end of the year. That is bad news for Iran.

European Union leaders have agreed on a landmark embargo of Russian oil that will seek to slash imports by 90 percent by the end of the year. The embargo represents a major intensification of European sanctions on Russia following the invasion of Ukraine.

For most oil producers, the embargo will be a boon. While the measures were widely expected and therefore may have been partly priced-in by traders, oil prices jumped on the news. Saudi Arabia, for one, is already planning how it will spend the windfall enabled by high oil prices.

But for Iran, and to a lesser extent Venezuela, the embargo of Russian oil is bad news. For countries whose oil exports are subject to U.S. or EU sanctions, China is the buyer of last resort. For several years, China has been the sole country to continue significant purchases Iranian and Venezuelan crude oil, ignoring the threat of U.S. secondary sanctions. These imports have been an important contributor to Iran’s economic resilience under sanctions. However, this is not because revenues are flowing back to Iran. The revenues accruing in China are being used to sustain Iran’s imports of crucial intermediate goods for the country’s manufacturing base.

Iran has also benefited from increased financial resources in the United Arab Emirates and Malaysia, two countries which are serving to intermediate Chinese imports of Iranian oil. Most Iranian oil arriving in China is declared as an import from the UAE or Malaysia. As it stands, Iran is consistently exporting more than 1 million barrels per day of crude oil to China.

Russia’s rise as a major energy exporter to China corresponds to the period in which Iranian oil was taken off the market due to the impacts of US, EU, and UN sanctions programmes—Iran’s demise as an oil exporter helped open the door for Russian exports.

The new EU embargo on Russian oil will intensify competition between Russia and Iran in China’s oil market. Russian suppliers are already offering buyers a 30 percent discount on benchmark prices, a much steeper discount than Iran has offered Chinese buyers in recent years. Russia and Iran will be competing for the business of the limited number of Chinese refiners willing to process “sanctioned” oil.

Already, some Chinese “teapot” refiners are replacing Iranian oil with Russian oil because of the attractive discounts on offer. So far, customs data does not reflect a dramatic swing away from Iranian imports. But it is early days and the embargo will dramatically change incentives. According to the IEA, around “60 percent of Russia’s oil exports go to OECD Europe, and another 20 percent go to China.” While some customers, such as India, might import the Russian barrels that would have otherwise gone to Europe, political and economic realities will require Russia to push more oil into the Chinese market.

Looking to Chinese customs data for April, Russia’s ability to squeeze Iran becomes clear. It is clearly a more important supplier of crude oil to China. While logistical bottlenecks might prevent an immediate jump in Chinese purchases, all of the Russian barrels already flowing to China are newly subject to discounts—China can insist on lower prices now that the EU embargo is in place. This in turn creates pressure for Iran to match Russian discounts or risk losing market share.

While it is possible that the further pressure on global supply might push oil prices even higher, minimising the loss of revenue for Iran even as Chinese imports fall, in the medium term, Russia has the means to bully Iran due to its lower fiscal breakeven price and lower production costs. At the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Vladimir Putin boasted that Russia could withstand oil prices of as low as $25 dollars per barrel for as long as a decade. Iran’s oil sector, already weakened by a decade of sanctions, does not have the same ability to endure low prices. In short, Russia can afford to undercut Iran.

Plus, for whatever period that Russian oil is not subject to U.S. secondary sanctions, Chinese tankers and refiners may prefer to handle Russian crude, due to the lower risk of enforcement action.

Iran has a couple of options here. First, it could try and negotiate an arrangement with Russia, agreeing not to engage in a race to the bottom when it comes to pricing their sanctioned barrels for China. Iran might even be able to play a role as an intermediary in Russian energy exports to China, importing refined products across the Caspian and exporting crude oil to China as part of a swap arrangement. But this kind of cooperation is highly unlikely given the track record of Russia-Iran relations and the fact that Russia sees Iran as the junior partner in the relationship.

The second option would be for Iran to try and get itself out of this predicament by taking decisive steps to restore the nuclear deal. Doing so would see the rollback of U.S. secondary sanctions on Iranian oil and enable the resumption of exports to European buyers precisely when those buyers need it most. Earlier this month, EU High Representative Josep Borrell commented on the heightened value of the nuclear deal for Europe in the wake of the Russia crisis. He told the Financial Times that “Europeans will be very much beneficiaries from this deal” as the “the situation has changed now.” He added that “it would be very much interesting for us to have another [crude] supplier.”

Earlier this week, Iranian officials boasted that oil revenues were up 60 percent year-on-year owing to the high oil prices. But the situation has changed now. As the EU moves forward with its historic embargo, Iran’s oil revenues are suddenly in Russian crosshairs.

Photo: Kremlin.ru

UAE Earns Big as Iran Sells Oil to China

Leaders in the United Arab Emirates are eyeing an economic windfall should the Biden administration succeed in its effort to return to Iran nuclear deal. But they have not waited for the lifting of sanctions to begin earning billions from Iran.

Leaders in the United Arab Emirates are eyeing an economic windfall should the Biden administration succeed in its effort to return to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). But they have not waited for the lifting of sanctions to begin earning billions from Iran.

During a press conference on Monday following consultations in Abu Dhabi, US Special Envoy for Iran Rob Malley told reporters that “all” of the Biden administration’s regional interlocutors had made clear they would seek “to find ways to engage Iran economically consistent with the lifting of sanctions that would occur” if the JCPOA were restored, a step that would also require Iran to return to full compliance with its nuclear commitments under the deal.

Malley added that should Iran and the P5+1 manage to restore the nuclear deal, it “would also allow countries in the region to develop closer ties economically with Iran.” Malley had understood from his conversations with GCC counterparts that this was “one of [their] goals.”

The comments were notable in light of recent developments in bilateral trade between the UAE and Iran. At first, the UAE was fully on board with the “maximum pressure” sanctions imposed by Trump on Iran in 2018 and so far maintained by Biden. In the Iranian calendar ending March 2019, roughly one year following the Trump administration’s decision to withdraw from the JCPOA and reimpose secondary sanctions on Iran, Iranian imports from the UAE declined 30 percent from around USD 8.2 billion to USD 5.7 billion, while exports to the UAE declined 11 percent from USD 6.7 billion to USD 6 billion. In this period, UAE leaders sought to tamp down on the burgeoning trade between the UAE and Iran, principally channelled through Dubai. Iranian companies and businesspeople were essentially hounded out of the country, as customers severed relationships and banks shut accounts.

But in 2019, the first signs of a change in policy began to emerge. Fearing a further deterioration in the regional security situation after limpet mines were detonated on commercial vessels in the Gulf of Oman in May and June of that year, the UAE opened a tentative dialogue with Iran. Trump’s Iran envoy, Brian Hook, traveled to Abu Dhabi in September 2019 to try and keep the UAE on board with the maximum pressure strategy. One month later, reports emerged that the UAE had released USD 700 million of Iranian assets that had been frozen as part of the UAE’s support for the U.S. sanctions campaign. A thaw in economic relations was underway.

In the Iranian calendar year ending March 2021, total Iranian imports from the UAE exceeded USD 9 billion, back to pre-sanctions levels. In the first five months of the current Iranian calendar year, imports have totalled over USD 5 billion, meaning that total annual imports are on course to exceed USD 12 billion by March 2022. The UAE is a major re-export hub, meaning that Iran sources goods from a wide range of countries from suppliers in the UAE. The growth in Iranian imports from the UAE has been so rapid that the Arab entrepôt has now replaced China as Iran’s top import partner.

In an interview in September, Farshid Farzanegan, head of the Iran-UAE Joint Chamber of Commerce, attributed the UAE’s rise as Iran’s top import partner to increased purchases of agricultural commodities from Dubai-based traders and an overall decline in China-Iran trade. But he also notes that the growth in imports is taking place despite continuing challenges in cross-border banking between Iran and the UAE related to the fact that US secondary sanctions remained in place. Moreover, the recovery in Iranian exports to the UAE has been comparatively modest—total exports are on track to be just USD 4.5 billion this year, still below their pre-sanctions levels. So how is Iran able to buy so much more from the UAE?

The answer probably has to do with the decline in China-Iran trade. Over the course of the last year, China has significantly increased its purchases of Iranian oil. These purchases, which are made in direct defiance of US secondary sanctions, are not reflected in the data produced by China’s customs authority. This is because Iran is not delivering oil directly to China. Iran’s deliveries are intermediated, meaning that the oil is taken to a third country, before being transferred onto tankers that deliver to Chinese refiners. When this oil arrives in China, it is declared as an import from the country serving as the waypoint. The two biggest countries playing that role are Malaysia and the UAE.

Looking at customs data for Chinese oil imports, the rise in imports from Malaysia and the UAE occurs precisely around the time that China begins to reduce direct imports of oil from Iran. At first glance, it might seem that China is simply buying more oil from existing customers as Iran ceases to be an option. But the volumes being purchased from Malaysia and the UAE are so great that the oil cannot come from the production of those two countries—it must be Iranian oil.

The amount of oil China is importing from Malaysia, estimated by dividing the monthly value of declared imports by the average monthly oil price is 94 percent higher so far in 2021 than it was in the six months leading up to the Trump administration’s full imposition of sanctions on Iranian oil in May 2019. Looking to the UAE, the same figure is 31 percent higher. Looking across the two periods, the crude oil price is just 4 percent higher meaning that the surge in the value of Chinese imports is not merely a function of higher oil prices.

The inclusion of Iranian oil in the Chinese customs data is even clearer when comparing that data to OPEC estimates for Malaysia and UAE oil exports. According to OPEC, Malaysia exported an average of 280,000 barrels per day of oil in 2020, the equivalent of just over 100 million barrels over the whole year. Based on the 2020 average market price of USD 41.75, China’s declared oil imports from Malaysia, which are valued at USD 13.6 billion, are the equivalent of 330 million barrels (some of this total is Venezuelan oil, also being imported by China via Malaysia). Doing the same calculation, the UAE’s export total, as reported by OPEC, is about 880 million barrels in 2020. The barrel equivalent of total imports declared by China is 290 million, meaning that China would account for one-third of all UAE oil exports—an implausible proportion.

Looking back to the significant trade deficit Iran is running with the UAE, the likeliest explanation for how Iran is able to finance this deficit, which may total nearly USD 8 billion in this Iranian calendar year, is that it is drawing on revenues related to the UAE’s role as an intermediary in oil sales to China. Iran is clearly not spending the money it is being paid by Chinese customers in China—there has been no rise in Iranian imports of goods from China in the period in which we know China has increased its purchases of Iranian oil. Rather, that hidden surplus in China-Iran trade is being spent, at least in part, in the UAE, and thereby making a direct contribution to the UAE economy during a critical period of post-pandemic recovery. Facilitating Chinese purchases of Iranian oil also allows the UAE to reduce the risks of regional escalation. Iran has repeatedly threatened to prevent exports by the UAE and other producers if its own exports are blocked by sanctions.

So it should be no surprise that GCC leaders told Malley that they seek to deepen economic engagement with Iran if the US lifts secondary sanctions. They have already increased economic ties to levels approaching those last seen before US sanctions were reimposed, even while sanctions remain in place. The thaw in economic relations between the UAE and Iran is an overlooked aspect of the recent developments in regional diplomacy and could prove an important driver for continued talks in bilateral and multilateral formats. The recent growth in trade also suggests that there has been a fundamental shift in the attitudes of Emirati policymakers, who rebuffed President Obama’s request for an increase in Arab diplomatic and economic engagement with Iran made during the 2016 US-GCC summit. In this way, the shared interests of Iran, China, and the UAE appear to be giving the Biden administration new and much-needed space to pursue diplomacy.

Photo: Chinese Foreign Ministry

Iran Gains Prestige, Not Power, By Joining China-Led Bloc

Although Iran’s accession to the SCO—which may take up to two years to complete—appears significant, the move is unlikely to substantially change Iran’s geopolitical position.

Last week, after fifteen long years in political limbo, Iran’s application to join the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) was finally approved. Iran first showed interest in the Chinese-led organisation in 2004, when it achieved non-member observer status. Although it first sought full membership in 2008, China and other member-states remained wary, primarily due to the impact of U.S-led multilateral sanctions, which made further political and economic entanglement with Iran a risky proposition. While India and Pakistan were admitted in 2017, continued instability in American policy towards Iran kept Sino-Iranian rapprochement on the back-burner. Since the Biden administration began to signal that it was open to negotiations with Iran, China made a renewed push for improved relations, culminating in the signing of a bilateral Comprehensive Strategic Partnership agreement with Iran in May of this year.

Despite these developments, Sino-Iranian relations remain limited and although Iran’s accession to the SCO—which may take up to two years to complete—appears significant, the move is unlikely to substantially change Iran’s geopolitical position. Despite Iranian rhetoric, the SCO is by no means an anti-Western alliance and is unlikely to furnish Iran much beyond symbolic support for its regional and international objectives. Iranian membership is also not a guarantee of increased Chinese investment or favourable policy decisions. In terms of dividends, Iran will have to make do with propaganda, prestige, and nationalist theatre for international and domestic audiences.

The Iranian government has touted membership in SCO as a means of opposing the United States and ending Iran’s diplomatic and economic isolation. Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi was unrestrained in his comments at the SCO Summit in Dushanbe, the capital of Tajikistan. “The world has entered a new era,” Raisi said, where “hegemony and unilateralism are failing.” He painted Iran’s membership in the SCO as emblematic of an increasingly multi-polar world, where smaller powers could work in tandem to limit the influence of larger powers. More to the point, he called on member states to support Iran’s civilian nuclear program and resist sanctions, which he called a form of “economic terrorism.”

Compared to the Iranian side, the Chinese press was more reserved. A report from Xinhua emphasized the SCO’s ability to foster a “regional consensus” and to connect Iran “to the economic infrastructure of Asia.” The news was presented alongside developments related to Afghanistan and Tajikistan, and while described as a “diplomatic success,” Iran’s membership was not cast as a key outcome fo the summit. Raisi’s exhortations to resist American unilateralism were not reported on at all. Xi Jinping’s summit address did not even mention Iran by name.

Despite the lofty rhetoric of the Iranian president, there are few ways in which the SCO will be able to directly confront American hegemony. As noted by Nicole Grajewski, the SCO is “governed by consensus, which limits the extent of substantive cooperation” between states with divergent policies and competing objectives. It also lacks any legal mechanisms to enforce its decisions or punish member-states that violate its policies or have conflict with other members. Far from the “anti-NATO” it has been portrayed to be, the SCO is more a “forum for discussion and engagement than a formal regional alliance.” Two of the eight present members, India and Pakistan, are close U.S allies, and neither China nor Russia are keen to openly challenge the U.S in the Middle East or Central Asia.

In short, Iran will gain the ability to participate in these discussions, but not in a way that is likely to strongly influence the organization or its policies. China and the rest of the member-states will be keen to avoid alienating the Arab states that see Iran as a regional rival. In a move that seems targeted directly at balancing this concern, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Egypt were also admitted during the Dushanbe summit as “dialogue partners,” joining nations like Turkey and Azerbaijan. While not full members, the presence of these voices will limit how much sway Iran will have at future SCO summits.

Furthermore, despite its own rhetorical commitment to facilitating trade, economic, and cultural ties between members, the SCO’s success in these fields has been limited. In terms of tangible projects, the SCO has mostly stuck to regional security initiatives like counter-terrorism intelligence sharing, cross-border efforts to fight drug trafficking, and joint military exercises. While the organization has lately attempted to re-brand itself as an economic development platform, it still lacks any institutions for multilateral development finance. Beijing and Moscow also have divergent interests when it comes to major issues like free trade zones, and questions remain as to whether the organization can function as an actual forum for holding practical negotiations between member states, rather than “simply becoming their vehicle for norm-making power projection.”

China and Iran have set ambitious targets to increase trade for nearly a decade, but bilateral trade remains modest despite repeated commitments, discussions, and international summits. There remain substantial barriers to investment. Chinese investors have been urged for years to invest in Iran’s free economic zones in Maku, Qeshm, and Arvand, but investment remains limited. While China is more than happy to ignore sanctions when it comes to oil imports, outside this strategic trade, Chinese firms remain unconvinced that the profit is worth the risk of doing business, and privately grumble about the difficulty of working with Iranian partners. Iranians also face disruption and competition from Chinese goods and services, leading to popular discontent and political blowback from Iranian companies that have profited from the absence of both Western and Chinese competitors. Although there is no question that there is vast potential in economic co-operation between China and Iran, these are not minor issues, and there is little reason to believe that the SCO will provide a forum to address the barriers.

The SCO provides an impressive stage for China and Iran to enact their shared opposition to Western sanctions, hegemony, and unilateralism. But the realities of international political economy and the conflicting agendas of the body’s member states means that joining the SCO is unlikely to empower Iran in a meaningful way.

Photo: Government of Iran

China Will Not Capitalise on the End of the Iran Arms Embargo

Sunday marked the expiration of a 13-year UN arms embargo on Iran. Iranian authorities have stated they are now free to buy and sell conventional weapons in an effort to strengthen their country’s security. But China, a major arms supplier in the Middle East, is unlikely to be making significant arms sales to Iran any time soon.

On October 18, the arms embargo imposed on Iran by the United Nations expired. The provision, which was part of UN Resolution 2231 (2015) that endorsed the Iran Nuclear Deal, expired five years after the resolution’s endorsement and a month after the failure of a U.S. attempt to extend its terms.

There has been some speculation that China will rush in to export conventional weapons to the Islamic Republic. Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif’s visit to Beijing two weeks ago no doubt set off alarm bells in Washington. China appears keen to maintain its reputation as a legitimate international player that abides by the rules. In July, Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hua Chunying stated, "China has practiced caution and responsibility in arms exports. And no one can criticize China for conducting regular arms trade with any country that does not violate international obligations."

Between dueling words from Beijing and Washington, the reality is that an influx of Chinese arms to Iran not track with the trend of Chinese arms sales in the Middle East or the broader Chinese-Iranian relationship, which is characterised by mutual anxieties. While the expiration of the arms embargo could offer some opportunities in the long-term, China is not set to become a major arms exporter to Iran.

Conventional weapons trade is a lucrative business in the Middle East. The countries of the region are consistently global leaders in arms imports. Purchases are on the rise—between 2014 and 2019, arms flows to the Middle East increased 87 percent. At the same time, the Chinese military is moderising and seeking advanced weaponry, propelled by the priorities of Xi Jinping’s rising China. While the Chinese defense industry will always have the People’s Liberation Army as their supreme client, arms exports have been encouraged by Beijing. The PRC ranked the world’s fifth-largest weapons exporter for the period of 2014-2019.

To be among the most competitive international defense contractors, Chinese companies need to acquire customers in the Middle East. China’s unique selling point for buyers in the Middle East is the promise of apolitical trade. The arms market, however, is not just a commercial market, but a political one as well. The PRC views the Middle East as a political tar pit and Chinese policymakers see the failures US policy in the region as a cautionary tale. But Chinese defense contractors have benefited from the region’s instability—the Middle East is an arena where Chinese weapons can be battle-tested.

China first made inroads selling weapons to Iran during the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s, a conflict in which it also sold arms to Iraq. Iran ordered fighter aircraft, tanks, guns, and missiles from the PRC. There were some sporadic orders in the 1990s and 2000s, the final one being in 2005, according to data compiled by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. After the imposition of international sanctions, no more orders have been recorded, though previously scheduled deliveries may have been taking place as late as 2015.

To date, there is no hard evidence of any major Chinese violations of international arms embargoes, although the U.S. has sanctioned Chinese defense companies before. International sanctions, which China voted for, have worked to halt Chinese-Iranian arms trade. Iran has not acquired the latest high-tech weaponry to come out of the Chinese defense industry. The PRC has supplied a majority of Iranian arms imports since 2006, but that is only by dint of international sanctions regimes. As in many fields, Iran is not paired with China by choice. Iran’s only other reliable supplier is Russia, with some sporadic business with Belarus, North Korea, Pakistan, and Ukraine. The end of the arms embargo is unlikely to return momentum to a trade relationship that has none. Even Russia, Iran’s only other realistic alternative for advanced weapons expiration the end of the arms embargo, faces its own hurdles and hesitations in selling arms to Tehran—Russia too is unlikely to prove a major weapons supplier to Iran.

While China’s sales to Iran have languished, arms sales to the countries like the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia have grown, reflecting that relations with Iran are just one pillar of China’s overall strategy in the Middle East. One of the Beijing’s diplomatic feats is maintaining relationships with regional powers such as Iran and Saudi Arabia, whose rivalry is responsible for a great deal of bloodshed.

Sales of unarmed aerial vehicles (UAVs), or drones, are a hallmark of China’s international arms sales. China has two series of drones on the international arms market: The Wing Loong I and II and the Chang Hong series, the most exported of which in the Middle East is the CH-4. The CH-4 drone is a medium-altitude, long endurance armed drone comparable to the U.S.-made Predator series, only cheaper. China has exported Wing Loong and CH-4 drones to Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Iraq, and Pakistan, but not Iran. Saudi Arabia and the UAE have both deployed CH-4 drones in the war against the Iranian-backed Houthis in Yemen, a fact sure to vex Iran. The sale of ballistic missile systems and certain kinds of long-range UAVs to Iran remain subject to a nuclear-weapons related embargo in force for a further three years.

Saudi Arabia also enjoys joint arms production with China. During King Salman’s visit to Beijing in 2017, one of the agreements signed included China’s first drone factory in the Middle East. King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST) signed a partnership agreement with China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) to manufacture the CH-4 drone line.

Iran has sought to address what it perceives as unequal treatment. In a leaked draft of the Chinese-Iranian Comprehensive Strategic Partnership agreement, there are provisions calling for joint defense production ventures as part of security cooperation. Whether such joint production enterprises will materialize has yet to be seen, as China has yet to even sell drones to Iran. Other Chinese efforts to invest in production in Iran have struggled, particularly oil and gas.

Selling a substantial arsenal to Iran would endanger China’s other partnerships in the region, to say nothing of heightening regional threat perceptions and tilting the Middle East towards further instability. The financial rewards of any such sales are not worth upsetting the entire basis of Chinese foreign policy in the Middle East.

Another pillar of China’s Middle East strategy is reliance on the U.S. security architecture in the region. While China has made its own strides in mobilising its naval fleet and leveraging a logistical base in Djibouti off the Gulf of Aden, these developments pale in comparison with the U.S. military presence in the region. The U.S. presence serves to secure the flow of oil from Middle Eastern producers to China. Significant arms sales to Iran could increase the likelihood of a confrontation between U.S. and Iranian forces in the Persian Gulf—an outcome Chinese policymakers fear. Furthermore, China’s relationship with the U.S. will always be a higher priority than its relationship with Iran. Historically, China has pulled back from engagement with Iran under U.S. pressure. Until the latest UN vote to extend the arms embargo in Iran, China generally did not defy the United States on Iran. In this regard, the vote was more of an ill-omen for U.S. multilateralism and the U.S.-China relationship than a material promise of China’s commitment to Iran.

Finally, there is also the matter of whether Iran can actually pay for large orders of advanced arms. Years of sanctions had taken their toll even before the COVID-19 crisis has ravaged the country’s economy and taken over 29,000 lives. Even with the appetite for defense spending of an increasingly militarised state, Iranian priorities will have to adapt, and Beijing’s motivation is profit. Additionally, the PRC does not manufacture the kinds of weaponry Iran covets. Iran is desperately in need of air-to-air machinery and air defense systems. Despite much effort, China cannot yet produce passable jet engines, and there are questions about its drones. China and Iran are mismatched when it comes to the weaponry on offer and spending capacity.

When it comes to trade, politics, and wider security, Chinese and Iranian interests can often align, but the partnership between the countries has not developed into a functional alliance. Certainly, the end of the UN arms embargo on Iran presents a long-term commercial opportunity for China’s defense industry. But in concert with both China’s ambitions and restraint in the region, it is unlikely that China will move to capitalise on the expiration of the arms embargo.

Photo: Wikicommons

Despite Public Outcry, Consensus Builds For China-Iran Deal

Iranian officials hope that the economic uplift of an implemented partnership agreement with China will win the hearts and minds of a wary public.

The relationship between Iran and China has improved considerably over the past two decades, but the two countries are far from enjoying the mutual understanding that is necessary for deeper strategic ties. Iranian public perceptions of China are increasingly, negative particularly in the aftermath of the coronavirus crisis.

In April, while the coronavirus was raging in Iran, health ministry spokesperson Kianoush Jahanpour called China’s official death toll a “bitter joke”. He then traded barbs with Chang Hua, China’s ambassador to Tehran, on Twitter. The Chinese envoy urged the Iranian official to “respect the great efforts of Chinese people.” This heated exchange drew the attention of many in Iran, while Jahanpour’s “unconsidered” remarks enraged conservatives.

Jahanpour later backtracked and was eventually replaced, but Iranian public opinion had turned against China, and social media users reprimanded the Rouhani administration for not standing behind their official. Things got so tense that the Chinese ambassador blocked a number of Iranian users on Twitter including a famous Iranian singer. Reformists also jumped into the fray, slamming Rouhani's government for its “unbalanced” ties with China.

It speaks to the complicated politics around Iran-China relations that the Rouhani administration has been accused of both being too dismissive and too dependent on China. Conservative politicians in Iran, who are eager for closer ties with China, have laid blame at the feet of the Rouhani administration for the dismal state of bilateral relations.

Ahmad Tavakoli, an influential conservative, has argued that Rouhani failed to welcome Xi Jinping warmly enough during a state visit to Tehran in 2016, sending his foreign minister to receive him on the tarmac. Hamid-Reza Taraghi, a political activist, recently claimed that “Some of [Iran’s] government officials have the wrong behavior towards our Chinese partners, and even the trip of Chinese President [ended up being useless] while it could have been the beginning of massive developments.”

Majid Reza Hariri, the Chairman of Iran-China Chamber of Commerce, told the hardline newspaper Kayhan, that following the implementation of the nuclear deal officials, in the Rouhani administration “talked to any Chinese official coming to Iran [in a way], as if [they] were his servants. He was [so] rest assured that Renault, Siemens and Total have formed a line [to invest in Iran] that he formally and publicly told Chinese that they are at the end of the line.”

While Xi Jinping signed a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (CSP) agreement with Iran during his state visit, little was implemented in the subsequent four years. Mahdi Safari, Iran’s former envoy to Beijing, stated recently that “The Chinese tell us that ‘you see us as spare parts, and when you get into trouble with Westerners and your relationship with them goes sour, you come to us.’” Adding that “We need to build trust to correct this perception.”

According to Gholamreza Mesbahi-Moghaddam, a former conservative MP, as the Rouhani administration exhibited “no determination” to pursue the CSP, Ayatollah Khamenei intervened, sending the then parliament speaker Ali Larijani on an important mission to Beijing last year in order to revive the languishing agreement. now that the Rouhani administration is belatedly pursuing a new 25-year framework for the CSP agreement with China, that Khamenei’s intervention is bearing fruit.

But the public sentiment towards China threatens to prevent the deal from progressing. As a leaked 18-page document detailing negotiating points for the new CSP circulated on social media and critics labelled the terms as another Turkmenchay—the 1828 treaty between Persia and Imperial Russia under which the Persian government ceded control of territory in the South Caucasus. Rumors circulated on social media that the deal would see Iran host Chinese military forces and to cede the island of Kish to the Chinese, prompting denials from Iranian authorities.

Even conservative political figures, perhaps surprised by the public reaction to news of the deal, sought to turn the criticism towards the Rouhani administration. The conservative camp had itself been subject to similar criticism when President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad signed a deal with Chinese officials in 2008 in an effort to safeguard oil exports in the face of international sanctions. The deal, which restricted Iran’s access to its own oil revenues, was also compared to Turkmenchay.

Hojjatollah Abdolmaleki, a prominent conservative political figure, cast doubt on the Rouhani administration’s ability to garner public support for the deal. Conservative figures even sought to amplify the rumors of embarrassing concessions. Mahmoud Ahmadi Bieghash, a newly elected radical MP, told claimed in an interview on state TV that the rumors about Iran ceding Kish to China were correct, but that “the [reaction] of people and parliament” forced a change in plans.

According to Fereidoun Majlesi, a former Iranian diplomat, the hardline politicians have found an issue around which to engage the wider public. “The radicals know that a large number of people are disappointed. Therefore, to attract their votes in the coming presidential election in 2021, they are bringing up such rumors to discredit their rivals, while portraying themselves as patriots,” Majlesi explained in an interview.

Despite their electoral ambitions, the strategic logic of an upgraded partnership deal between Iran and China is undeniable for Iranian authorities across the political spectrum. The conservative Farhikhtegan newspaper heralded the deal as “[the best opportunity] through which Iran can target the core of the maximum pressure policy,” referring to the sanctions reimposed by the Trump administration in November 2018.

Prominent economist Saeed Laylaz recently stated the agreement with China “will return balance to Iran’s foreign relation, while averting the exceeding demands of US and is [also] a response to Europe’s inaction,” adding that “Those who [care] for Iran should welcome this agreement. Because it both reduces the pressure on the country and increases our bargaining power against the West.”

Laylaz explained that Iran has no option but to pursue a more functional relationship with China. “If we do not use this opportunity with China, the West will never give us a chance. [Our] experience has shown that the West is nothing but the United States until further notice. Counting on Germany or the European Union is similar to building a house on the sands by the sea,” he said.

This view was echoed by Diako Hosseini, a senior director at the Centre for Strategic Studies, which is affiliated with the presidency. “Prior to US withdrawal from the JCPOA, strategic cooperation of Iran and China was just a choice. After US withdrawal, it was turned into a 'preference,” he tweeted. Hosseini added that the Trump administration’s maximum pressure sanctions made such a deal a “priority,” and that further economic pressure would make the deal as “necessity,” describing any such agreement as the “price the [U.S.] should pay.”

Clearly, there is a growing consensus that an agreement with China would bolster Iran’s hand in future negotiations with the U.S. by increasing the means by which to survive the pressure of U.S. sanctions. However, some in Tehran are worried about Beijing’s ability to take advantage of Tehran’s current weak economic position.

Majlesi told Bourse & Bazaar that “Iranians are naturally worried that the Chinese will follow the playbook of Russians regarding Iran. For a period of time, Russia used Iran as a winning card to solve its own problems with the U.S. However, I strongly believe that China has unique abilities and if they decide to help us, they are certainly able to do so. “

Despite these headwinds, the Rouhani administration appears newly determined conclude this agreement. Mahmoud Vaezi, chief of staff to the president, has asserted that the negotiations on the document are likely to be "concluded by the end of the [Persian] year” (before March 2021).

An informed source told Bourse & Bazaar that this agreement “will be implemented during Rouhani’s presidency for sure,” adding that the political consensus in Iran is now clear, despite the public rhetoric. “Currently, there is no problem with implementing the agreement on the side of Iran, and everything is now dependent to China.”

No matter what administration is to come next, the Iranian political system and Ayatollah Khamenei will adamantly pursue the 25-year deal in order to more fully implement the CSP first signed in 2016. The hope will be that an economic uplift from China’s renewed commitment to Iran will win the hearts and minds of a wary public.

Photo: IRNA

Iran’s Pact With China Is Bad News for the West

Tehran’s new strategic partnership with Beijing will give the Chinese a strategic foothold and strengthen Iran’s economy and regional clout.

By Alam Saleh and Zakieh Yazdanshenas

A recently leaked document suggests that China and Iran are entering a 25-year strategic partnership in trade, politics, culture, and security.

Cooperation between China and Middle Eastern countries is neither new nor recent. Yet what distinguishes this development from others is that both China and Iran have global and regional ambitions, both have confrontational relationships with the United States, and there is a security component to the agreement. The military aspect of the agreement concerns the United States, just as last year’s unprecedented Iran-China-Russia joint naval exercise in the Indian Ocean and Gulf of Oman spooked Washington.

China’s growing influence in East Asia and Africa has challenged U.S. interests, and the Middle East is the next battlefield on which Beijing can challenge U.S. hegemony—this time through Iran. This is particularly important since the agreement and its implications go beyond the economic sphere and bilateral relations: It operates at the internal, regional, and global level.

Internally, the agreement can be an economic lifeline for Iran, saving its sanctions-hit, cash-strapped economy by ensuring the sale of its oil and gas to China. In addition, Iran will be able to use its strategic ties with China as a bargaining chip in any possible future negotiations with the West by taking advantage of its ability to expand China’s footprint in the Persian Gulf.

While there are only three months left before the 2020 U.S. presidential election, closer scrutiny of the new Iran-China strategic partnership could jeopardize the possibility of a Republican victory. That’s because the China-Iran strategic partnership proves that the Trump administration’s maximum pressure strategy has been a failure; not only did it fail to restrain Iran and change its regional behavior, but it pushed Tehran into the arms of Beijing.

In the long term, Iran’s strategic proximity to China implies that Tehran is adapting the so-called “Look East” policy in order to boost its regional and military power and to defy and undermine U.S. power in the Persian Gulf region.

For China, the pact can help guarantee its energy security. The Persian Gulf supplies more than half of China’s energy needs. Thus, securing freedom of navigation through the Persian Gulf is of great importance for China. Saudi Arabia, a close U.S. ally, has now become the top supplier of crude oil to China, as Chinese imports from the kingdom in May set a new record of 2.16 million barrels per day. This dependence is at odds with China’s general policy of diversifying its energy sources and not being reliant on one supplier. (China’s other Arab oil suppliers in the Persian Gulf region have close security ties with the United States.)

China fears that as the trade war between the two countries intensifies, the United States may put pressure on those countries not to supply Beijing with the energy it needs. A comprehensive strategic partnership with Iran is both a hedge and an insurance policy; it can provide China with a guaranteed and discounted source of energy.

Chinese-Iranian ties will inevitably reshape the political landscape of the region in favor of Iran and China, further undermining U.S. influence. Indeed, the agreement allows China to play a greater role in one of the most important regions in the world. The strategic landscape has shifted since the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq. In the new regional order, transnational identities based on religious and sectarian divisions spread and changed the essence of power dynamics.

These changes, as well as U.S. troop withdrawals and the unrest of the Arab Spring, provided an opportunity for middle powers like Iran to fill the gaps and to boost their regional power. Simultaneously, since Xi Jinping assumed power in 2012, the Chinese government has expressed a stronger desire to make China a world power and to play a more active role in other regions. This ambition manifested itself in introducing the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which highlighted the strategic importance of the Middle East.

China grasps Iran’s position and importance as a regional power in the new Middle East. Regional developments in recent years have consolidated Iran’s influence. Unlike the United States, China has adopted an apolitical development-oriented approach to the region, utilizing Iran’s regional power to expand economic relations with nearby countries and establish security in the region through what it calls developmental peace—rather than the Western notion of democratic peace. It’s an approach that authoritarian states in the Middle East tend to welcome.

U.S. President Donald Trump’s withdrawal from the nuclear deal with Iran in 2018, and the subsequent introduction of the maximum pressure policy, was the last effort by the U.S. government to halt Iran’s growing influence in the region. Although this policy has hit Iran’s economy hard, it has not been able to change the country’s ambitious regional and military policies yet. As such, the newfound strategic cooperation between China and Iran will further undermine U.S. leverage, paving the way for China to play a more active role in the Middle East.

The Chinese-Iranian strategic partnership will also impact neighboring regions, including South Asia. In 2016, India and Iran signed an agreement to invest in Iran’s strategic Chabahar Port and to construct the railway connecting the southeastern port city of Chabahar to the eastern city of Zahedan and to link India to landlocked Afghanistan and Central Asia. Iran now accuses India of delaying its investments under U.S. pressure and has dismissed India from the project.

While Iranian officials have refused to link India’s removal from Chabahar-Zahedan project to the new 25-year deal with China, it seems that India’s close ties to Washington led to this decision. Replacing India with China in such a strategic project will alter the balance of power in South Asia to the detriment of New Delhi.

China now has the chance to connect Chabahar Port to Gwadar in Pakistan, which is a critical hub in the BRI program. Regardless of what Washington thinks, the new China-Iran relationship will ultimately undermine India’s interests in the region, particularly if Pakistan gets on board. The implementation of Iran’s proposal to expand the existing China-Pakistan Economic Corridor along northern, western, and southern axes and link Gwadar Port in Pakistan to Chabahar and then to Europe and to Central Asia through Iran by a rail network is now more probable. If that plan proceeds, the golden ring consisting of China, Pakistan, Iran, Russia, and Turkey will turn into the centerpiece of BRI, linking China to Iran and onward to Central Asia, the Caspian Sea, and to the Mediterranean Sea through Iraq and Syria.

On July 16, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani announced that Jask Port would become the country’s main oil loading point. By placing a greater focus on the development of the two strategic ports of Jask and Chabahar, Iran is attempting to shift its geostrategic focus from the Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Oman. This would allow Tehran to avoid the tense Persian Gulf region, reduces the journey distance for oil tankers shipping Iranian oil, and also enables Tehran to close the Strait of Hormuz when needed.

The bilateral agreement provides China with an extraordinary opportunity to participate in the development of this port. China will be able to add Jask to its network of strategic hubs in the region. According to this plan, regional industrial parks developed by Chinese companies in some Persian Gulf countries will link up to ports where China has a strong presence. This interconnected network of industrial parks and ports can further challenge the United States’ dominant position in the region surrounding the strategically vital Strait of Hormuz.

A strategic partnership between Iran and China will also affect the great-power rivalry between the United States and China. While China remains the largest trading partner of the United States and there are still extensive bilateral relations between the two global powers, their competition has intensified in various fields to the point that many observers argue the world is entering a new cold war. Given the geopolitical and economic importance of the Middle East, the deal with Iran gives China yet another perch from which it can challenge U.S. power.

Meanwhile, in addition to ensuring its survival, Tehran is going to take advantage of ties with Beijing to consolidate its regional position. Last but not least, while the United States has been benefiting from rivalry and division in the region, Chinese-Iranian partnership could eventually reshape the region’s security landscape by promoting stability through the Chinese approach of developmental peace.