What Iran Needs is a New Social Revolution

Economic inequality is the single most important issue in Iran. All of the country’s political and social ills pour forth from the crucible of inequality. A successful political transition in Iran requires more than just identifying problems, it requires a positive vision for Iran and solutions to the country’s problems. But no opposition leader, whether inside or outside of the country, has managed to explain how they will deliver economic justice in Iran. Until such a positive vision emerges, there is nothing for protestors to rally around but slogans and a shared expression of anger.

To their credit, Reza Pahlavi and his boosters have done some work to set out their vision for Iran’s transition. There is a lot to say about their vision, including the striking level of institutional continuity even they are willing to accept were they to inherit the state structures of the Islamic Republic. But the critical flaw of their plan is a stunning failure to address the issue of inequality.

In the six papers on “Economic and Social Stabilization” published by NUFDI and endorsed by Pahlavi, there is barely any examination of inequality. In fact, across the reports, which total 164 pages, the word “inequality” appears only once. This is an extraordinary blind spot and it points to a failure to see the political conditions in Iran for what they really are.

Most critics of the Islamic Republic falsely believe that the reason the country has struggled economically is because of the role of state ownership in the economy and the creation of a bloated welfare system that represents a kind of Islamic socialism. They believe that economic reforms in Iran require cutting red tape, respect for private property, reliance on market mechanisms, and fiscal discipline. In other words, they are calling for classic neoliberal interventions. But these are precisely the reforms that have been attempted by the economic policymakers of the Islamic Republic for nearly three decades, spearheaded by economists who were trained in the United States and United Kingdom to worship the likes of Friedman and Mankiw.

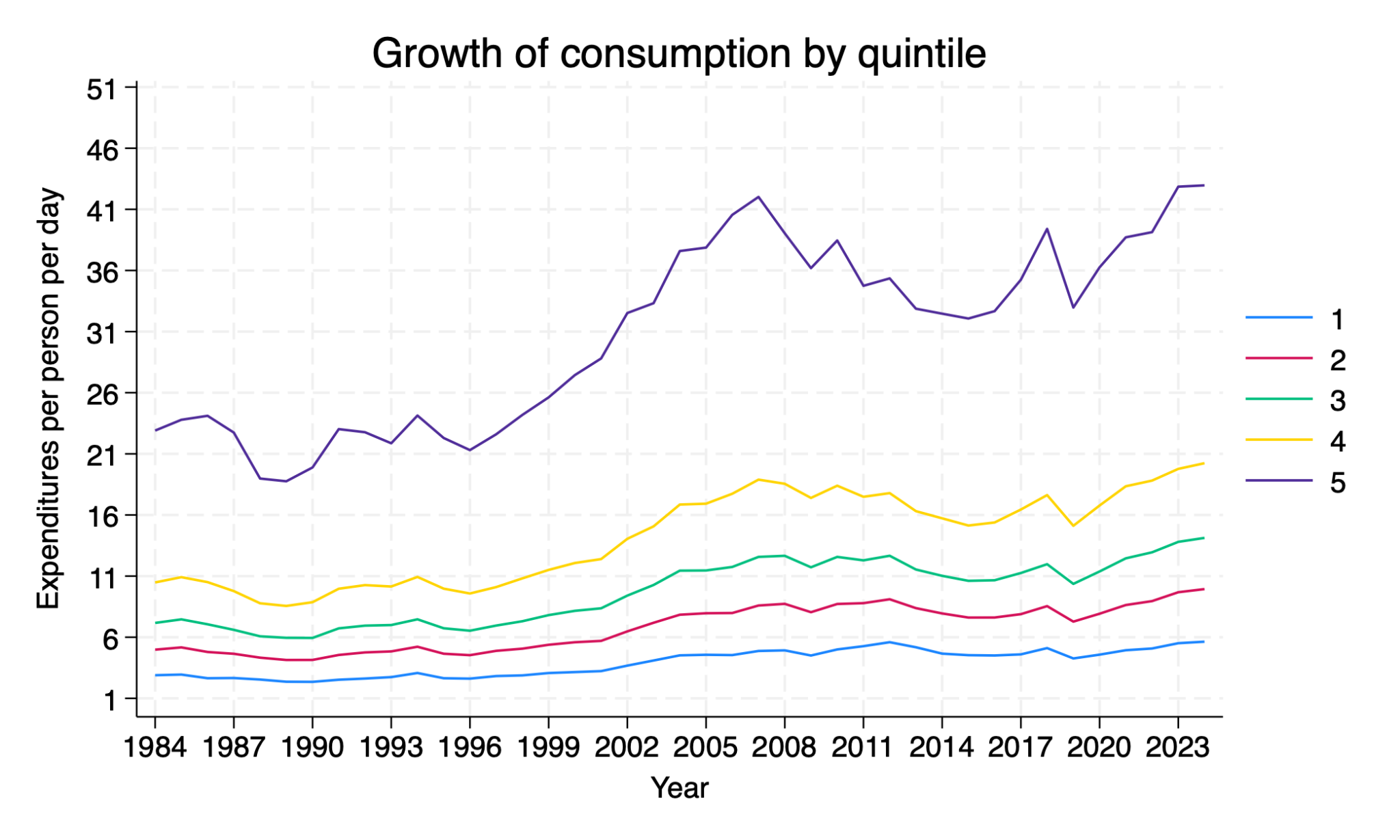

The reason these reforms have failed is not because the Islamic Republic did not understand neoliberalism, the reason is that the Islamic Republic applied neoliberal ideas in an environment where they were prone to abuse. Iran’s current leaders basically undertook their own version of shock therapy, which raised living standards from the early 1990s to the mid-2000s but did so in a manner that concentrated purchasing power among a small elite (see the chart below from Djavad Salehi-Isfahani, which uses data from Iran’s Household Expenditures and Income Survey).

At the same time, across multiple administrations, the economic program eroded the authority of the administrative state in ways that allowed economic elites to put their interests above those of the rest of society. There was no effort to rein in rampant financialization and speculation, no organised industrial policy, no protection of welfare spending. The state relied on economic growth to forestall social tensions. But the rich wanted a bigger piece of the pie and the state did not stop them from grabbing it, even when the pie ceased growing under sanctions. Social provision in Iran remains intact, but its structures are groaning under the weight of these economic contradictions.

In the 2023 wave of the Arzesha-ha va Negaresh-ha Iranian (“Values and Attitudes of Iranians”) survey, a robust nationally representative poll fielded by Iran’s Ministry of Culture, respondents were asked “Do you think the gap between the rich and the poor has widened or narrowed compared to five years ago?” A significant 88 percent of respondents reported that the gap had widened. Moreover, 78 percent of respondents agreed with the statement that “In our society, the rich get richer every day, and the poor get poorer.”

In light of these sentiments, why don’t people like Pahlavi address the issue of inequality? A few reasons come to mind. First, a political opposition rooted in the deeply unequal United States, boosted by prominent Republicans, and supported by a wealthy diaspora who like low taxes, small government, and want to “Make Iran Great Again,” is probably ideologically incapable of addressing the issue of inequality in Iran.

Second, even if there is some ambient awareness of the problem of inequality, there may tactical considerations. In the immediate future, the Pahlavi camp’s best hope for “revolution” relies on elite defections, given the repeated failure of protests to reach a critical mass. Understandably, if you want economic elites to get on board with your political program, you are not going to talk about real class politics.

Finally, any true reckoning with the issue of inequality would reveal uncomfortable truths, including the fact that exacerbating inequality was an intentional aim of U.S. sanctions policies, which were callously endorsed by the diaspora. Iranians were made poorer so they would become angrier. With one hand tied behind their backs by the Islamic Republic, and another hand tied by the United States, they were pit against the rich, who have remained out of reach in their proliferating office towers and hilltop villas. This has been its own injustice.

One reason I do not believe we have arrived at a decisive moment in Iran’s political transition, let alone a moment of revolution, is that we are not even talking about the stakes in Iran using the right language and we have yet to envision a transition that deals with the main grievances in the country. We are still in the process of clarifying the stakes and identifying solutions.

As we make progress towards some kind of fundamental political change in Iran—I strongly believe progress is being made—it is important to recognize that Iranians are not seeking a political revolution, they are seeking a social revolution. Alongside their political rights, Iranians are demanding economic opportunity and social dignity. In this context, a democratic transition without economic redistribution will achieve nothing—it will not be able to consolidate.

The reason the political project of the Islamic Republic has failed is because of the failure to redistribute wealth successfully and sustainably, especially as sanctions stymied growth. Most economies around the world are breaking with the neoliberal consensus. Iran should do the same and pursue state-led investment to drive productivity growth, renew the commitment to social welfare to reduce economic precarity, and ensure purchasing power is spread across the income distribution more equitably.

The uncomfortable reality is that the drivers of today’s protests today are the same as those behind the protests in 1978-1979. The political economy of the Pahlavi Monarchy and Islamic Republic are strikingly similar—two systems that accumulate wealth for the rich through forms of renterism and economic repression. We all know a democratic system will be better for Iran, but what economic system will break this cycle that pits the weakened poor against the strengthened rich? Until we answer that question, there will be no successful political transition, even if the Islamic Republic is pushed over the edge.

Photo: IRNA